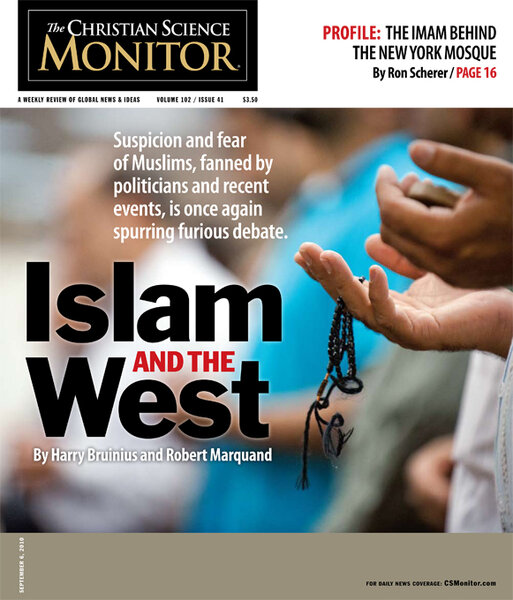

Why 'Islamophobia' is less thinly veiled in Europe

Loading...

| London and Paris

Rooful Ali is an accountant who commutes, "suited and booted," to his corporate office in London from Northamptonshire, England, where he grew up in a Bangladeshi family. His avocation is photography. But he also finds time to direct the first Europe-wide association of Muslim professionals.

The group includes marine biologists, lawyers, professors, astrophysicists, executives, doctors, artists, and political and civic figures in 10 countries – chosen for their accomplishments. They give inspirational talks and mentoring workshops for young people in the Muslim community.

Mr. Ali is part of a second generation of Muslims just starting to get traction in Europe. It is a generation that drives their kids to school, worries about office deadlines, loves sports, participates in the arts, and owns businesses. Ali and some of the 70 others in his professional network believe that Muslims can give something to European society by acting as role models within their own community.

Yet in the current political and social climate in Europe – where a larger and more visible Muslim presence is causing a backlash – they face strong head winds. Not only is mainstream Europe looking more askance at Muslims, but younger Muslims with higher expectations and hope for belonging are growing more restless.

"Much of the depiction of Muslims is without sufficient knowledge," Ali says. "Iraq, Afghanistan, the Taliban – that's how we are seen. It's sad. We would like to showcase who we are in a good way."

VIDEO: American Muslims on misconceptions about Islam

It is Europe, not the United States, where the West and Islam exist in closest daily proximity. Some 20 million to 30 million Muslims live here, making up about 4 percent of the population compared with less than 1 percent in America. Mosques, once an urban phenomenon, are found in far corners of the Continent. Muslims are more visible on European streets, and most are not professionals, but work in retail, agriculture, food service, and labor.

In the US, the controversy over the proposed Islamic center near ground zero has brought some of the most visible instances of public Islam-bashing, mostly on the right side of the political spectrum – a departure from the line taken by President Bush after 9/11 not to equate Islam with terrorism.

But in Europe a pushback against immigrants, many of whom are Muslim, has been under way for much longer. A postwar Europe long priding itself on cosmopolitan tolerance is facing a population seen as different – at a time of concern about the economy, jobs, and when mainstream Europe isn't quite sure about its security and its future.

"Values of national identity and patriotism are starting to take shape over an older argument in Europe about tolerance, plurality, freedom of expression," says Edward Mortimer, vice president of the Salzburg Seminar in Austria, which helped launch the Muslim professionals network.

The past year has a brought a wide range of anti-Islamic measures. Switzerland passed a referendum to ban minarets on mosques. Belgium has prohibited the burqa, or full-length veil worn by Muslim women, and France is about to.

In June, voters in the Netherlands – whose second-largest city, Rotterdam, has a majority population of ethnic minorities – made the party of anti-Islam political figure Geert Wilders the third largest in Dutch politics. Mr. Wilders's platform calls for banning the Koran and new mosques, taxing head scarves, and ending immigration from Muslim countries. Wilders is now in negotiations to join the ruling coalition. He is also scheduled to appear on Sept. 11 alongside former US House Speaker Newt Gingrich at a ground zero commemoration in New York.

Such politics has engendered Muslim antipathy in parts of both the right and the left. Over the past five years, "Islamophobia" has become more mainstream and more comfortably settled. Social politeness and taboos on talking about Islam are eroding at a time when Europeans aren't exactly sure what they think about Islam.

The ground zero debate in Europe, for example, has brought a small geyser of anti-Muslim invective, even on websites like Le Monde's. They included an often articulate though sometimes churlish depiction of Islam as a single monolithic form of faith, inherently violent and extreme, and of Muslims as incapable of being moderate.

"Racism is the lowest form of human stupidity, but Islamophobia is the height of common sense," is the motto of a Danish group called "Stop Islamization of Europe," which somewhat typifies a broader sentiment.

An essay on a French leftist website, AgoraVox, spoke of shock that in the same week German authorities closed a radical Hamburg mosque, New York City authorities approved the Islamic center: "The Mayor, instigated by an imam who is said to be 'moderate,' plans to build a mosque extremely close to Ground Zero, where stood the Twin Towers that Islamist fanaticism reduced to rubble.... You rub your eyes and read again. No, it is not a hallucination ... you look for the justification ... but instead of understanding, you dive deeper into an impression of unreality."

Ironically, the head of the Grand Mosque in Paris, Dalil Boubakeur, said he thought a "mosque at ground zero" was too provocative – though it was not clear if he knew the proposed siting was two blocks away. As Mohammad Shakir, communications director for several small Muslim charities in London, put it, "I've never seen a mosque with a basketball court before. Muslims need a place to pray if you build a Muslim community center. But it is a terrible misnomer to call this a 'mosque at ground zero.' "

After 9/11, a small industry of literature, much of it produced in the US, predicted a coming "Eurabia" – a tsunami of Islam that will make Europe unrecognizable, where Muslim birthrates overwhelm older populations, mosques are as plentiful as McDonald's restaurants, and Islamic sharia law supplants European constitutions.

A German central banker, Thilo Sarrazin, has kicked up a firestorm with a pending new book attacking Turks and Muslims. "I don't want the country of my grandchildren and great grandchildren to be largely Muslim, or that Turkish or Arabic will be spoken in large areas, that women will wear headscarves and the daily rhythm is set by the call of the muezzin. If I want to experience that, I can just take a vacation in the Orient," are among Mr. Sarrazin's passages, which were challenged by German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Daniel Luban, a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago, offers in a recent paper that many of the core assumptions of "Islamophobia" in the US spring from Europe. "While the political operatives behind the anti-mosque campaign speak the language of nativism and American exceptionalism, their ideology is itself something of a European import. Most of the tropes of the American 'anti-jihadists,' as they call themselves, are taken from European models."

Justin Vaïsse, an analyst at the Brookings Institution in Washington, argues that actual data about Muslim birthrates in Europe (which are declining as Muslims assimilate and have smaller families) and immigration (500,000 a year) belie the dire projections of the Continent becoming Eurabia.

"The paradox of this genre is that it dwells on the heated controversies and tensions taking place in Europe while at the same time claiming that Europeans are in denial of their problems," says Mr. Vaïsse, coauthor of "Integrating Islam: Political and Religious Challenges in Contemporary France." "And the emphasis on the anecdotal tends to obscure the fact that, from the fight over minarets in Switzerland to the debate over head scarves in France, current tensions are part of a normal and democratic process of adjustment, not the first signs of an impending catastrophe."

Often absent are views of Muslims themselves. Much of the discussion aimed at Islam takes place as if the Muslims weren't in the room. Scant attention is paid to vast religious and cultural differences between groups. French Muslims tend to be from Arab and African states, British Muslims from South Asia, Dutch Muslims from Morocco and Indonesia, German Muslims from Turkey.

Muslims, interviewed at mosques, offices, and cafes in Paris and London, say they often don't recognize common depictions of themselves. They resent the fact that Islam is a subject of derision and reject the stereotype of Muslims as being one uniform, slightly sinister group.

Tufyal Choudhury, a law lecturer at Durham University in England and the primary author of an 11-city study on Muslims in Europe, notes that Muslim concerns are not about spreading the faith, but housing, education, and neighborhood safety. Young second-generation Muslims have high expectations but often feel excluded. "Their parents had less expectations and less disappointment," he says.

A recent French government study found that job applicants with Arab Muslim names had less than half the chance of getting an interview than applicants with French names.

One Muslim, Said from Cameroon, interviewed at a Paris mosque before prayers, points out that Europe is a place of liberty for Muslims, many of whom have escaped repressive states. Some come to escape orthodox Islam while still being devout. More Muslim women find Europe a harbor to challenge older "cultural" models of Islam that restrict their freedoms. Muslims agree that some younger adherents get radicalized. But others are eager to integrate. They want to be European, or French, or Dutch. In university settings and among some Muslim moderates, frank reappraisals of the Koran are under way, which includes a tougher look at its calls for militancy.

Ahmet Mahamat is one who wants to integrate. A slender immigrant from Chad with luminous eyes, he has lived in Paris for 15 years. He is a filmmaker working on a documentary about the civil war in his home country. When he first arrived in France, he says he was impossibly idealistic. He still describes the streets of Paris rhapsodically. But in recent years he has felt targeted as a black and a Muslim. Muslims, he says, are now seen as a problem. Trust is low on both sides. "We hear it all the time: Terrorism is a shortcut that links to immigration," he says. "Immigrants are linked to criminality or delinquency or fanaticism."

As a filmmaker, Mr. Mahamat uses the Hollywood classic "Casablanca" to make his point. "At the end of 'Casablanca,' Humphrey Bogart certainly is the man that shot the German officer. But who do they round up? The usual suspects – probably local Muslims. The new obsession here with Islam is very strange, because our world doesn't lack problems. We've got global warming, poverty, famine, dictatorships ... we don't have small issues. But we are focused on Islam. We need a usual suspect."

He adds, "There is an African saying, 'that if you are with someone long enough, you can look in their eyes and eventually see yourself.' But now I feel this African saying is wrong. I look in the eyes of so many people and what I see does not correspond to who I am. They see another me."