More turf wars for Japan after Russia's Medvedev visits disputed Kuril Islands

Loading...

| Moscow

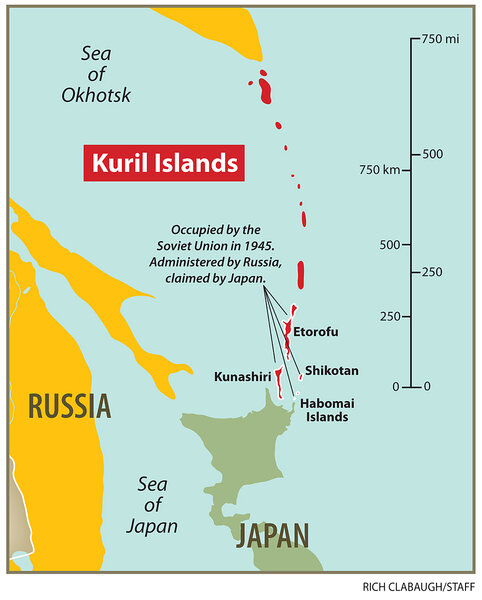

President Dmitry Medvedev has triggered a huge diplomatic flap with Japan, with whom Russia is still officially at war. He ruffled Japan by staging a visit Monday to the disputed Southern Kuril Islands, four tiny specks of land seized by the Red Army in 1945 and claimed by Japan as its own "Northern Territories."

Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan told parliament Monday that Mr. Medvedev's decision to become the first Soviet or Russian leader to set foot on land Japan regards as its own was "extremely regrettable." Foreign Minister Seiji Maehara said the visit "hurts our national sentiment," and called in the Russian ambassador to Tokyo to deliver an official note of protest.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov slammed back, telling journalists that the Japanese reaction to Medvedev's visit was "unacceptable," adding, "this is our land and the Russian president visited Russian land. It's an entirely domestic matter."

Moscow insists that the four tiny volcanic islands just off the northern tip of Hokkaido are rightfully Russian territory, endorsed by wartime agreements between the Allies at Yalta and Potsdam. But Tokyo argues that, unlike other post WW II territorial transfers, the legal case with the Kuril Islands remains murky and subject to further negotiation.

Most experts say the fate of the Kurils is the single reason Japan and Russia have failed to sign a formal peace treaty in the 65 years since the war ended, and there is no more certain way to stoke national passions in both countries than by raising the issue.

So why did Medvedev, returning to Moscow from a state visit to Vietnam, go several thousand miles out of his way to spend a morning on a barren rock that the Russians call Kunashir Island, the closest of the four to Japan?

"Medvedev wants to show the people of Siberia and the far east that he cares about them, and aims to develop these lands," says Yevgeny Bazhanov, vice rector of the Foreign Ministry's Diplomatic Academy in Moscow, which trains Russian diplomats.

"But it's also a signal to the Japanese that this is our land, and if they want to discuss that, they need to sit down at the table and talk with us," he says. "There have been no negotiations. The Japanese behave as though they won World War II, and that's not the way to go about it."

The episode could cloud Russian-Japanese relations just as Medvedev prepares to travel to Yokohama in two weeks time for a summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, where Russia has been hoping to carve out a more prominent role for itself.

The four islands, with a population of about 18,000, have been a forgotten backwater at the farthest tip of Russia since the war, known only for their diplomatic notoriety.

But they provide Russia access to valuable fisheries, hold significant mineral deposits, and could sit at the heart of major new oil and gas discoveries.

"We want people to remain here," Medvedev told islanders. "Development is important. We will definitely be investing money here."

The USSR, which bore the brunt of fighting Nazi Germany, only entered the Pacific war on Aug. 8, 1945, two days after the US had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and barely a week before Japan's surrender.

But Soviet forces moved rapidly to roll up territories, including Sakhalin Island and the Kuril Islands, that they believed had been promised them under wartime accords.

"There were lots of territorial changes as a result of World War II, in Europe and in Asia," says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a Moscow-based foreign policy journal. "It's a Pandora's Box that shouldn't be opened. [Giving back the Kuril Islands to Japan] would be taken as a precedent" by other countries whose borders were changed, he says.

But the Soviet Union did appear to admit the Kurils were an exception by agreeing, in 1956, to give two of the islands – Shikotan and the Habomai islets – back to Japan during peace negotiations that were never concluded.

Russian experts say that deal is still theoretically on the table.

"We've said many times that we're ready to return those two islands in exchange for normalizing relations," says Mr. Bazhanov. "But for Russia it's absolutely not urgent. We own these islands, and it's lawful for us to be there."

Though relations between Russia and Japan have been cordial, despite the formal state of war, experts say that major economic cooperation will probably have to await the settling of the territorial dispute.

"Japan is a special country," says Mr. Lukyanov. "They can't do business apart from politics. So we won't see massive economic investment until this issue is dealt with."

But polls show that the idea of territorial concessions are extremely unpopular among the Russian public, and today's Kremlin leaders might not be able to follow through on the Soviet-era offer to return two of the disputed islands even if Japan took them up on it.

"The only outstanding issue that divides Russia and Japan today is those four microscopic islands," says Bazhanov. "But compromise is always easier to say than to do."