Whither Russia's immigration debate?

| Moscow

The mass migration of the poor to the developed world – along with the cultural shifts, social tensions, and political polarization that erupt in its wake – is far from a uniquely Russian story. Both the United States and Western Europe have their own versions of the problem, and no country is doing a smooth job of dealing with it.

But Russia remains far behind the curve, even in terms of developing a national debate over the way forward. At least US President Obama has a comprehensive strategy for immigration reform, backed by a variety of civil society and political forces, even if he can't figure out a way to get it through Congress.

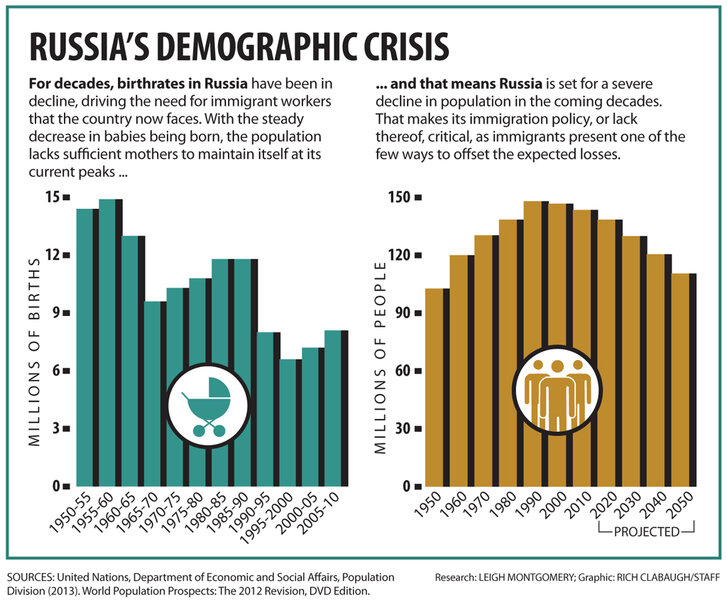

October's Biryulyovo riot was a wake-up call that has set Russia's news media abuzz with commentary and dire warnings of more unrest to come. Yet official reactions so far suggest that the government seems almost allergic to planning for the long-term implications of Russia's shrinking workforce or devising a path to attract and integrate immigrant labor into local communities.

In his only official remarks about the interethnic discord in Moscow, Russian President Vladimir Putin blamed local authorities for failing to forestall the unrest.

Various bits of draft legislation put forward by the pro-Kremlin United Russia party in the wake of the riot would toughen border controls, reduce the time legal migrant workers could stay in the country, and reduce employers' quotas to invite legal workers to take jobs Russians don't want.

"United Russia is thinking backwards. They should first find Russians who want to do this work, then propose amendments to limit migrant workers," says Svetlana Gannushkina, head of the committee for Civil Assistance, one of a handful of Russian nongovernmental organizations that addresses the issue of migrant labor.

She says the number of illegal workers in Russia is about 11 million, or almost 10 times as high as the 1.2 million who are here legally. "Some public organizations are working on ways to help migrants adapt. There is some thinking going on in the State Duma [parliament] about the need for a concept of immigration, but no one is attacking the main problem, which is that illegal immigration is driven by bribes and corruption," she says.

"Businesses don't have to pay illegal migrants properly, or pay taxes for them. Officials and police extract bribes from the migrants and the businessmen who employ them. Here is a system, a chain, from the unprincipled businessman to the corrupt official to the nationalist politicians whose rhetoric keeps migrants in a state of fear and convinces the public that migrants are the source of all problems. How do you break that chain?" she asks.

In other countries, immigrant groups and civil society organizations play a role in helping governments shape policy, and legislators can offer alternatives.

"This is not a government that thinks strategically; they mostly do short-term firefighting. Hence we get rhetoric to lay the blame on someone else, and police measures to round up some migrants," says Masha Lipman, editor of the Moscow Carnegie Center's Pro et Contra journal. "Policy is made by a limited number of people in a completely nontransparent way. The State Duma doesn't debate or study the problem because its function is to write the laws the Kremlin tells it to. Input from below, from civil society, is not invited because the authorities are wary of autonomous players."

Perhaps the danger of incipient social explosion, as illustrated by Biryulyovo, will focus minds in the Kremlin and lead to a broader public debate, experts say.

"The state should recognize this problem, and should change its policies" before it's too late, says Alexander Verkhovsky, head of SOVA, another civil society group that works with migrants.

"It's a complicated task, but it needs to be done."