Global leadership: Voters launch a power surge of women

Loading...

| Baltimore

When Johanna Sigurdardottir campaigned to be prime minister of Iceland last year, she vowed to bring an end to the "age of testosterone."

It was a reference to the international banking meltdown that destroyed her country's financial system. But the gender dynamics were also clear: Ms. Sigurdardottir was suggesting that men had had their chance and that it was time for women to take over. Her center-left party won by a landslide.

Iceland may be unique in its gender equity. The World Economic Forum called the country the world's best at closing gender gaps in economics, health, education, and political representation; in March, Iceland banned strip clubs – for feminist, not religious, reasons.

But globally, as far as women in politics goes, the concept is becoming altogether mainstream.

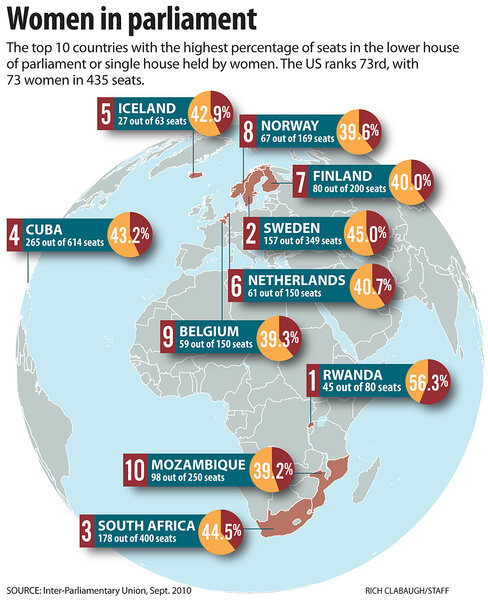

Over the past decade, almost every region of the world has seen exponentially more political seats – legislative and executive – go to women. Iceland's 42.9 percent female representation in the legislature, for instance, now sits in the rankings behind South Africa's 44.5 percent, Cuba's 43.2 percent, and Rwanda's 56.3 percent, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU).

More men than women voted for her

Eighteen countries also have women as heads of state. Earlier this year, Julia Gillard took over as prime minister in Australia, Iveta Radicova became the first female prime minister of Slovakia, and Roza Otunbayeva took power in Kyrgyzstan after street protests toppled President Kurmanbek Bakiyev.

Most recently, on Oct. 31, former guerrilla Dilma Rousseff won a bruising runoff campaign to become Brazil's first female president. A Pew Research Center poll in September found that at least 70 percent of Brazilians viewed the idea of a female executive positively; other local polls indicated that more men voted for Ms. Rousseff than did women.

"There is definitely a shift," says Leslie Schwindt-Bayer, a professor at the University of Missouri who has written extensively on women in politics. "We've certainly seen around the world an increase of women in national politics. And the women who are winning positions these days are quite different than the women who were winning these positions in the past – they're not winning because of family connections; they're not taking over the position of a family member who died in an assassination. They're winning on their own merits."

Scholars and advocates caution that the female power surge does not always lead to improved socioeconomic status or increased rights for women. The amount of power wielded by a head of state varies, and studies show that women have more often moved into the weaker executive slots.

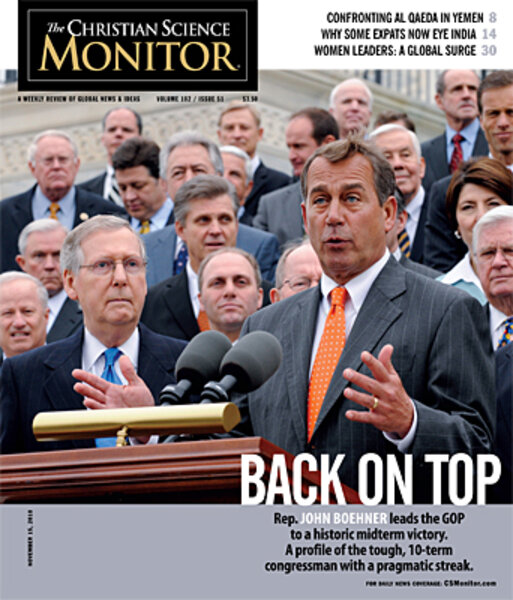

Moreover, female representation seems to have flat-lined the world's most powerful countries – in particular, the United States. Although pundits called this election year in the US the "Year of the Republican Woman," the reality was far less dramatic. While significantly more Republican women ran in House primaries (128), fewer won (47) than in 2004. And despite some high profile victories – Nikki Haley becoming South Carolina's first woman governor, or Kelly Ayotte taking one of New Hampshire's Senate seats – the overall number of female governors stayed the same, at six, and the number of women in Congress overall stayed about the same. The Inter-Parliamentary Union ranks the US 73rd in the world in terms of female representation, tied with Turkmenistan.

"There's a misconception about where we are when it comes to women and politics," says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women in Politics at Rutgers University in New Jersey. "Because we have the Hillary Clintons, the Nancy Pelosis, the Sarah Palins, it gives the sense that these women are everywhere. But women make up a really small proportion of our elected officials."

Overall, though, the face of global power is clearly changing, scholars say. And it is looking far more feminine.

It started with a UN conference

To understand this shift, you need to go back to 1995, said Mona Lena Krook, a political scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, when the United Nations held its Fourth World Conference on Women, in Beijing. Thousands of government representatives, advocates, and interested laypeople debated all sorts of topics related to women over 10 days – everything from education to reproductive rights to women's role in development. They also talked about political power.

"Women's equal participation in political life plays a pivotal role in the general process of the advancement of women," states the final report. "Women's equal participation in decisionmaking is not only a demand for simple justice or democracy but can also be seen as a necessary condition for women's interests."

The report recommended that governments restructure their electoral and political party systems to better enable female representation. No longer should women's rights be the focus only of feminist and advocate groups, the conference concluded: It should be a mainstream goal for mainstream institutions. And one recommended way of adjusting political systems, the report said, was through gender quotas.

Gender quotas, which vary in structure but typically reserve political seats or spots on a ballot for women, have existed in a handful of countries since the 1930s. They came into vogue in the 1970s among European leftist parties, and started to gain more widespread traction in the '80s. But it was this Beijing conference, Ms. Krook says, that made the concept palatable to a wider variety of countries.

"Representatives could go home and argue that this was a global norm," she explains.

Since the conference, nearly 100 additional countries have instituted some form of political gender quotas. And between 1998 and 2008, the global average of the proportion of women in national assemblies increased 8 percent, to 18.4 percent, according to the UN Development Fund for Women. This contrasts with the increase of just 1 percent between 1975 and 1995.

Quotas work best in parliamentary systems

Some nations saw an increase when they instituted quotas – such as in Ecuador, where the percentage of women legislators increased from 3.7 in 1996 to 17.4 percent in 1998. But not every country's quota worked so effectively. Paraguay, for example, saw no change at all, with 2.5 percent both before and after the quota.

Part of the reasoning for this, say political scientists, is that quotas are created differently – placement mandates that compel parties to alternate women and men on their ballots, for instance, do better than an instruction for a party to make a "good faith" effort to include women.

They also function primarily in parliamentary, multiparty systems, as opposed to in, say, the US, where the candidate who gets the most votes wins.

But overall, Krook and others say, the quotas have shifted more political power to women – and women's power to new regions.

A number of countries from Southern Africa – where quotas are encouraged by regional bodies such as the Southern African Development Community – sit in the top tiers of the IPU's ranking of female legislative participation; Latin America is also well represented. Even Afghanistan and Iraq, which adopted gender quotas when they designed their post-American intervention political systems, now have more female representatives than does the US.

Women's perspective on lawmaking

What these numbers actually mean for women's rights, is another issue. Many advocates claim that increased female representation will more likely bring so-called "women's issues," such as child care and reproductive health, to the political forefront.

"We bring a totally different perspective to the issues – we have to run the family household, balance the budget, raise the kids," says Anne Mackenzie, who served in the Florida legislature for 16 years.

Ms. Walsh, at the Center for American Women in Politics, agrees. There are many examples of female members of Congress recognizing, and then adjusting, laws or institutions that were discriminatory, she says. It was a group of bipartisan women, for instance, who changed the National Institutes of Health's policy to study only men in drug trials; it was a Republican woman who pushed to create the Family Medical Leave Act.

Because of this, both Walsh and Ms. Mackenzie are involved in a movement to recruit women candidates of both parties to run in 2012, when redistricting will mean that more races will be without an incumbent – something that has traditionally worked in favor of women politicians.

"Women bring a different set of life experiences to the making of public policy," Walsh says. "They see the world differently. It's why you want all sorts of diversity."

But other studies suggest that this sort of outcome is less than a given. Many countries with high female representation still fall low on charts measuring gender equity in education, economics, and health, scholars point out.

"As to whether the numbers [of women in legislatures] are turning into real power – that's an ongoing issue," Krook says. "Is there a potential wave of political transformation because of these quota policies? It's an ongoing question."

The same goes for the elite group of women who make it to the top levels of political power. As in legislatures, the number of women winning heads of state positions has increased significantly over the past decade, with many countries – Slovakia, for instance, and Liberia – electing their first female president or prime minister in the past few years.

But Faria Jalalzai, a professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, says there is no "standard" policy stance for these women heads of state, and that it is also important to understand the power distinctions among leaders before making any sweeping statement about the rise of women in the global executive club.

Glass ceiling broken, or just cracked?

"There are such divergences in power," she says. "It's not the same to say that a woman is the president of Ireland as [it is to say] that a woman is the president of the United States."

(Ireland has a largely ceremonial head of state, a position now filled by Mary McAleese. The president of the United States is a powerful executive.)

Ms. Jalalzai says her research shows that female politicians are more likely to move into the less powerful slots – one reason that Pakistan, for instance, has had a female head of state (Benazir Bhutto), while the US, although fielding high-profile female candidates (Hillary Clinton for president in 2008, Geraldine Ferraro for vice president in 1984, and Sarah Palin for vice president in 2008) has not.

"There is such a diversity of cases," she says. "In some countries, the glass ceiling really is shattered. In others, it's just kind of cracked."

But at the same time, she and others say, women leaders are often given less credit than they are due. An oft-heard refrain about women leaders, particularly in developing countries, is that they are in power because of familial ties.

This has certainly been true, political scientists say, but it can also be overstated. News articles about the recent death of former Argentine President Nestor Kirchner, for instance, repeatedly mention how he was the husband of current Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and describe him as the "power behind the throne" and the "strongman" in her government.

Few note that the political duo met in law school, and that Cristina was elected to national political office first.

•Taylor Barnes contributed to this article from Rio de Janeiro.