Haiti earthquake anniversary: the state of global disaster relief

Loading...

| Port-au-Prince, Haiti; and Mexico City

For most of his adult life, Emmett Fitzgerald has hopped around the globe with not much more than a few suitcases of belongings and a big heart, landing in broken or violent or dysfunctional nations. He has built cholera clinics in the jungles of Congo (former Zaire), taught English in remote Tanzanian schools, and identified international health crises for Bill Gates's charity.

So last January, when he watched TV images of dazed or hysterical Haitians fleeing the still shuddering debris of a magnitude-7.0 earthquake that killed 230,000 in an instant, Mr. Fitzgerald – who was in London at the time – knew he'd soon be in Port-au-Prince. He recalls thinking, as he watched a man save a woman's tent shelter from being destroyed in a tropical downpour, "Yeah, that's where I want to be.' "

By May, he'd hit the ground in the scorching Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince. And, as manager of a camp of survivors, he has spent nearly every waking hour since bouncing from the makeshift schools where children are tutored under tents; to the substation for UN soldiers who patrol the camp; to the cholera clinic where patients, if they can sit at all, perch atop cots.

Fitzgerald – a blond Irishman with a perpetual five o'clock shadow and skin reddened by the Haitian sun – is one of tens of thousands of humanitarian nomads who wander the globe responding to disasters – tsunamis, earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, drought, famine, and war. They are aid workers like Fitzgerald who coordinate emergency services, the doctors operating on patients in improvised hospitals, the firefighters pulling bodies from rubble, the volunteers handing out food and water, and the engineers rebuilding homes.

They are sustained by the estimated $15 billion a year that governments, foundations, and individuals send to help their fellow men. That money flows – sometimes in a trickle, sometimes in a flood – to people on the ground like Fitzgerald, whose job can be as stultifying as shuffling papers or as electrifying as the time he commandeered a pickup truck to rush a Congolese woman dying of cholera to a clinic and save her life.

Today he manages one of the hundreds of camps strewn across Port-au-Prince – Terrain Acra. The camp sits on a hilly swath of land with a PVC pipe factory on it that's also named after the Acra family, which owns it. It is a jumble of rusting corrugated metal and bright blue tarps that sprang up spontaneously after the earthquake and is now home to 26,000 survivors.

For the Haitians who live there, Fitzgerald is the face of the aid agencies they depend on for thousands of gallons of drinking water daily, new tarps to replace torn ones, makeshift schools for their children, and medicine when they're sick.

He's also the first to receive their anger. Fitzgerald once stayed away from the camp for a day after a retaining wall fell and killed two children. Although his organization, Minnesota-based American Refugee Committee, had nothing to do with the wall's construction, he was fearful the residents would hold him responsible.

"It feels like being the mayor of a town at times," he says. "Everything is my problem, only I don't have the jurisdiction to deal with it."

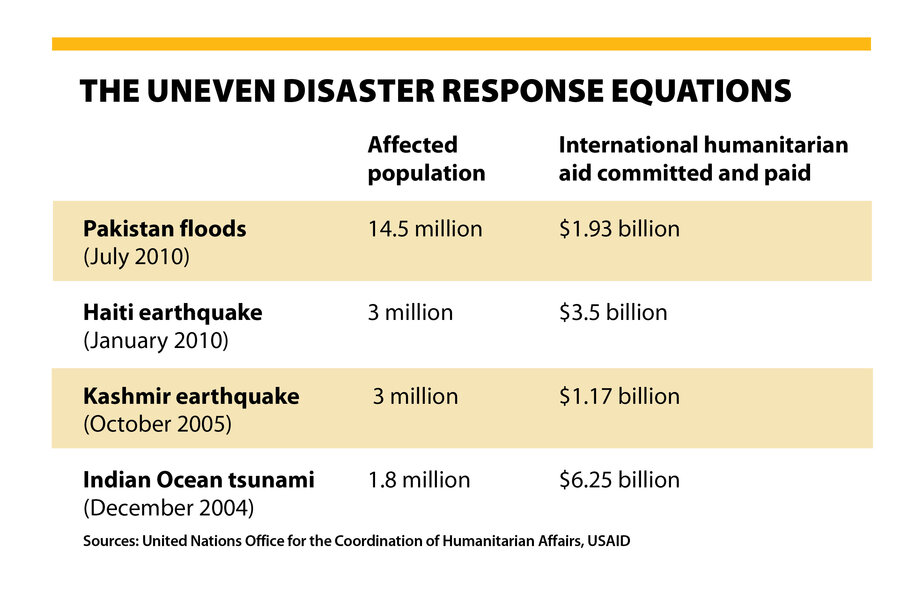

And the problems are enormous. Despite nearly $10 billion in short- and long-term aid pledged in the past year, and the presence of at least 10,000 nongovernmental organizations, a year later, roughly 1 million Haitians are still crammed into 1,200 camps, rife with violence and such tight, unsanitary conditions that cholera has begun to spread. Port-au-Prince's streets are still filled with rubble and collapsed buildings. And only $1.6 billion in humanitarian assistance has actually been spent, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (OCHA estimates that $1.9 billion more has been committed to programs, so far.)

So, a year after the quake riveted the world's attention and sparked an outpouring of goodwill, it's easy to ask: Is the global humanitarian system accomplishing its goals? Is it leaving societies better off – and should it be? Are global expectations, formed by 24-hour news coverage and instantaneous social networking, increasingly disconnected from the realities of what humanitarian agencies can accomplish in the first place?

Disasters – whether sudden and dramatic tsunamis, slow and devastating droughts, or intractable civil conflicts – have always afflicted humankind. But shoring up humanity on a large scale after massive upheaval is a modern idea – it wasn't until after World War II that governments and individual donors began to mobilize money and hands-on help, taking on a crucial role in crises around the globe.

Today humanitarian experts say they are responding to more disasters – perhaps, they say, because of climate change, perhaps because more people are moving into vulnerable places, but definitely because awareness of need through the media is now instantaneous.

And the world is responding with a fury. Communications and globalization, technology and transportation have made once-isolated corners of the world accessible to aid groups, journalists, militaries, and volunteers. The way aid is funded, shepherded, delivered, and evaluated is constantly evolving and, ideally, improving.

The humanitarian business is booming, says Antonio Donini, who worked with the United Nations for 26 years and now studies the evolution of humanitarian aid at the Feinstein International Center at Tufts University in Medford, Mass. "From a marginal activity in conflict [zones] with the International Red Cross and a few others present to alleviate the suffering of combatants, it has become a huge enterprise" that mobilizes billions of dollars a year and employs 250,000 people.

But, Mr. Donini adds, "professionalization has not followed the growth. There are efforts to create better performance, there are standards … but it is still a work in progress."

The industry, increasingly technically competent and efficient, is still bogged down in key areas, including coordination, local partnering, accountability, and preparedness.

Too many helping hands?

In early February, a convoy of aid workers in supply trucks set out across Port-au-Prince, rumbling for three hours over and around debris to an impromptu camp that OCHA reports indicated was in urgent need of food.

But when the convoy rolled up to the camp, the aid workers were flabbergasted to see a small group of volunteers, unaffiliated with official relief efforts, already handing out food, unaware of the larger network of coordination by OCHA, says Jeff Wright, a World Vision worker who was in the convoy.

Untold masses of well-intentioned individuals who descended on Haiti exacerbated one of the biggest challenges in the aid world: how to coordinate all the helping hands.

When the earthquake struck, the biggest international groups – Doctors Without Borders, UNICEF, Oxfam – were on the ground, as always.

"The critique of coordination coming from a lot of small and amateur aid providers tends to be that they say, 'We are out there actually helping while big NGOs are coordinating.' But the irony is that they are creating problems," says Mr. Wright. "The volume of need for food distribution was so great.... We [did] not want to be double-serving anyone."

A lack of coordination between NGOs in the Haitian camps resulted in such lapses in services that six months after the earthquake, 40 percent of camps still had no access to water and 30 percent had no toilets of any kind, notes Mark Schuller, an anthropologist at York College at the City University of New York who studied conditions in the Haitian camps last year.

But globally, over time, coordination between agencies has improved vastly, aid experts say. For example, during 1998's hurricane Mitch in Central America, where Wright also served, he says NGOs were tripping over each other in some places while leaving gaping holes in services in others. OCHA's cluster system, rolled out in the past few years, places other UN agencies and international NGOs in charge of various aspects critical to relief and recovery, such as nutrition, camps, or sanitation.

"The cluster system has improved the way coordination is done," says Jan Kellett, who worked for 10 years in recovery, from Sudan to Afghanistan, and now is program leader at the British-based Global Humanitarian Assistance, which tracks humanitarian funding.

But not everyone in the growing field of players participates. Participants must assign staff full time to meetings and other administrative tasks – which effectively excludes smaller organizations without the manpower. "It takes bandwidth; it takes discipline," says Wright. "It can feel, when you are in it, that you are doing a lot of sitting around in meetings not getting stuff out to people."

Coordination was tested to its limits during the Haiti relief effort. As aid workers describe it, any group of well-meaning Americans who bought plane tickets, donned matching T-shirts, and stuffed supplies in their suitcases could come and call themselves an agency.

"The bulk of people that went to Haiti had no idea how we coordinated ourselves," says Daniel Wordsworth, president of American Refugee Committee, which plans to teach the coordination system to individual doctors, nurses, carpenters, architects, and other volunteers this year. "People were screaming that there was no coordination. But organizations that had experience were very committed to working within the established system."

What happens after media leave?

As the humanitarian industry has grown, so, too, have expectations – of donors, recipients, and societies at large – about what humanitarian aid can accomplish and how fast a problem can be solved.

When the media coverage – both by the traditional press and real-time citizen journalism – is as relentless as it was in Haiti, touching heartstrings from Ohio to Oslo, outsized expectations emerge.

Sometimes the media just don't cover a disaster heavily – as in the devastating flooding in Pakistan last year, which easily affected millions more people than the quake did in Haiti. But CNN, for example, mobilized to Port-au-Prince immediately after the quake, and its nonstop coverage for weeks is widely considered to be what spurred the massive individual giving and later the billions promised by donor governments.

As always, the TV crews pack up eventually, and people assume "problem solved." When the tragedy comes back into the spotlight, as Haiti did after cholera emerged in October, viewers were shocked to see Haiti looks much as it did Jan. 13, the day after the earthquake.

But that doesn't mean failure, aid experts say. "Most people see an emergency, see aid workers rush in and do stuff, and ... six months later, they think it is all over. But the amount going into long-term aid [for disasters, globally] has been going up," says Peter Walker, a veteran aid-industry worker and now director of the Feinstein International Center. Typically, two-thirds of spending runs for more than three years; a third of spending for more than eight years, he says. "Humanitarian aid just keeps people alive. It does not change why they got there in the first place."

If any example illustrates a disconnect between expectations and realities, it's the housing situation in Haiti, where little permanent housing has been built since the quake, says John Ambler, senior vice president for programs at Oxfam America. "The housing issue really goes back to fundamental problems of land title. People cannot just rebuild. Owners of land will not let them rebuild," Mr. Ambler says. "It shows how difficult it can be to address recovery efforts when the basic rules of the game are not well organized."

These kinds of roadblocks aren't exclusive to the developing world, says Irwin Redlener, a physician and director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. He points out that five years after hurricane Katrina in the United States, there are at least 20,000 children – 60 percent of those displaced – suffering mental-health problems or still living in temporary or unstable housing divisions.

Genocide sparked relief reforms

It was the Rwandan genocide in the 1990s that brought the kind of soul-searching that leads to reforms. Despite the presence of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across the country, more than 800,000 people were slaughtered – some in operations plotted in NGO-run refugee camps. "The genocide happened with aid agencies sitting there," says Mr. Walker. "The sense of failure and guilt that came out of that was just overwhelming."

Aid groups began to ask themselves: How can we do better? How can we be more accountable to donors, the beneficiaries we assist, and the societies our work affects after we're gone?

A flurry of standards and accountability initiatives was tried, such as the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership International (HAP), which in 2003 became the sector's first self-regulatory body to ensure accountability to beneficiaries.

A set of standards called "Sphere" was created in 1997 by a group of NGOS and the Red Cross and Red Crescent movement to improve the effectiveness of the aid response. In a handbook translated into at least 20 languages, Sphere sets out minimum standards for latrine installation, caloric needs, and daily water requirements, among other necessities.

Donini, who also served in Afghanistan with the UN in the early 1990s, says the system has institutionalized crisis response. He remembers crises erupting in Afghanistan in 1990 when groups came in with different sets of plastic sheeting or types of latrines. That, he says, meant some beneficiaries did not receive the same quality of care as others: "If you are measuring need using different measuring sticks, it creates confusion.… It does not allow verification that all vulnerable groups are receiving the required assistance."

And yet, while Sphere provides a meaningful barometer for NGOs, the standards aren't adjusted for each country or disaster, and so a "cookie-cutter" approach is often unrealistic in the heat of tragedy. In Haiti, for example, each family in the tent cities should have a living space of 15 feet by 12 feet. But by the time aid organizations reached the Port-au-Prince camps, shelters were already set up in far more cramped spaces.

"That's the kind of thing that if you planned it out, you could meet the standards," says Fitzgerald. "But when you're confronted with an environment like Terrain Acra, which grew up spontaneously, it's not realistic. In order to meet [standards], I'd have to plow a path through the middle and destroy a bunch of tents, and I just can't do that politically."

And no one is going to require that he does – a drawback with Sphere and HAP and other efforts to hold humanitarian groups accountable. Nobody requires participation or punishes failure to adhere to standards, says Walker. The industry is slowly moving toward discussions about international certifications "with more teeth," he says, and perhaps even licenses to practice.

Emotion sells; prevention, not so much

When Sally Austin was dispatched to Sri Lanka for CARE International to head relief and reconstruction programs after a massive earthquake triggered tsunamis across 14 Asian nations on Dec. 26, 2004, killing 230,000 and destroying 400,000 buildings, she found herself with thousands of homeless people and no experience building homes.

"In terms of bricks and cement and trying to get into construction and all the challenges, there was nobody in CARE that I could turn to for support," says Ms. Austin, who now heads emergency operations for CARE International in Geneva.

She sought advice from colleagues and plodded along. In the end, CARE programs built 1,938 homes in Sri Lanka and 1,776 in Aceh, repairing nearly 400 more. They also reorganized their emergency response, creating an emergency shelter team in Britain. So when Austin arrived in the recovery phase of Haiti's earthquake in May, she was not as daunted. By the end of October, CARE had built 495 transitional shelters in Haiti.

And CARE is not alone. As the aid industry seeks to improve its response, it is starting to put more emphasis on preparedness and risk reduction. That might include more training of local staff in disaster-prone areas, prepositioning supplies in places hit by hurricanes annually, reforesting hillsides, or working with governments to have disaster recovery scenarios in place.

For UNICEF, that has meant more sophistication in supply operations, so that its warehouse in Copenhagen, Denmark, is not the starting point when a tragedy hits halfway around the world. Emphasis on preparedness has often meant the difference between life and death, says Patrick McCormick, a spokesman for UNICEF, especially in places prone to cyclones, like Bangladesh. He says cyclone death tolls have decreased dramatically over the years.

There is a clear upward trend in donor country contributions to disaster prevention and preparedness: It increased threefold in 2008 to $325 million, according to data from Global Humanitarian Assistance. But prevention yields much less anteing of donations than an outright disaster evokes in emotional donations.

Is aid part of the problem?

Goodwill can cause real problems if it's administered with a tin ear to local knowledge and concerns. For example, when international relief agencies swept into one devastated area after the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, they offered more replacement fishing boats than had been lost by fishermen, despite concerns about overfishing in the area, notes a 2007 tsunami aid assessment report by the Tsunami Evaluation Coalition, a multiagency body.

"International action was most effective when enabling, facilitating, and supporting local actors," the report states. "International agencies often brushed local capacities aside."

Some of the boats weren't constructed well and proved unsuitable in the long term.

The victims in the tragedy were later surveyed, and their satisfaction with how humanitarian groups met their needs progressively declined as the response phase turned into recovery.

Similar studies on local perceptions of humanitarian assistance across 12 countries, from Afghanistan to Nepal, in 2006 and 2007 by the Feinstein International Center, found that the values underpinning humanitarian action are accepted across religions and cultures.

But, says Donini, "the bad news is that the baggage that aid agencies bring – the big white vehicles, the top-down nature of activities ... creates tension between insiders and outsiders."

Aid experts say that recovery is always most successful when the national government or military plays a strong role. "They know the context, they know exactly what people want and need," says Mr. Kellett. "If you have national ownership of human recovery you will have better delivery. They are staying around. They are not an international group arriving and then going on to the next disaster."

But on the ground, he says, especially when governments and NGOs are among the victims of crisis, that ideal is hard to put into practice.

Haiti has been particularly fragile in this sense. The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, it was already highly dependent on aid before the quake. The temblor decimated an overcrowded city full of shoddily built houses and slums and decapitated an already weak government, destroying ministries and the presidential palace, and killing scores of government workers.

And as recovery plods on, frustration has mounted – aimed at both the government and the international community. Jean Dimanche, a small-grocery salesman who lost his home and shop Jan. 12, is typical in his discontent. He says the Haitian government and aid agencies aren't telling the public what they plan to do with all the money they've received: "We know that money has come from all around the world and we're [grateful], but we don't see how they're using it."

Is Ms. Derisier served?

If an observer were to look around Terrain Acra, he might understand many of the frustrations emerging in Haiti. Here, for all the work Fitzgerald and his team have put into the camp, it hasn't changed much in a year.

Mirlande Derisier, a teacher who literally wore the rubber from the soles of her shoes walking Port-au-Prince streets after the quake to check on relatives and friends, many of whom were later found dead, ended up at Terrain Acra.

Though furnished with a wicker sofa, a few books, and a portrait of a close friend who died in the temblor, Ms. Derisier's tarp shelter doesn't feel safe like home. At night as she sleeps on the padded floor, she has lain in motionless fear as thieves sliced her tarp walls, reaching in for anything they could grab and make away with.

Yet she, like others here, has no prospect of leaving anytime soon. There is no housing and no job to return to. She has even less incentive, with services in the camps far superior to those in the neighboring slum where she lived before it was destroyed.

Getting people out of the camps and back to neighborhoods will be the principal goal in the next phase of work in Haiti, and aid workers, once on the front lines of saving lives, now grapple with getting Haitians back on their feet, not stuck in dependence on aid agency water or housing.

Fitzgerald questions how to move forward every day: "We need to start looking at how these services we provide have become magnets that draw people to the camp."

He plans to help bring the community services – like water supply – up to speed, while slowly beginning to charge for services. "We can't start saying camps shouldn't exist until we can say that we've given people a realistic option in their community."

Striking the balance is difficult: Take away services too quickly, and lives are at risk . "We should be realistic about these dates and say to ourselves that a certain number of people are going to be in these camps for three, four, or five years," Fitzgerald says. "Nobody wants to admit that's the reality."

Part of the delay in moving forward in Haiti, as in the wake of other tragedies, is the ideal to "build back better." But that raises its own set of questions, says Walker. "I have to be accountable to the individuals I am assisting. But I also have to be accountable to people I am not assisting. What happens if you have a community, and you take disaster victims ... and they end up better off than the rest of the community? Is that fair and right? Are you accountable to the next generation?"

All of these questions – whether the industry is respecting non-Western standards; remaining neutral in conflict; or letting governments get away with passivity at best, and sometimes even negligence – should remain firmly in the humanitarian consciousness, aid workers say.

"There are certain conflicts that may be extended, attenuated, exacerbated by the existence or nonexistence of aid. We have to continue to examine whether private aid lets a government off the hook, whether it allows governments not to fulfill its responsibilities." says Ambler, of Oxfam.

"We have to ask ourselves, on a case-by-case basis: Is aid part of the problem or part of the solution?