Rape trial: Are the kids of China's rich and famous getting special legal treatment?

Loading...

| Beijing

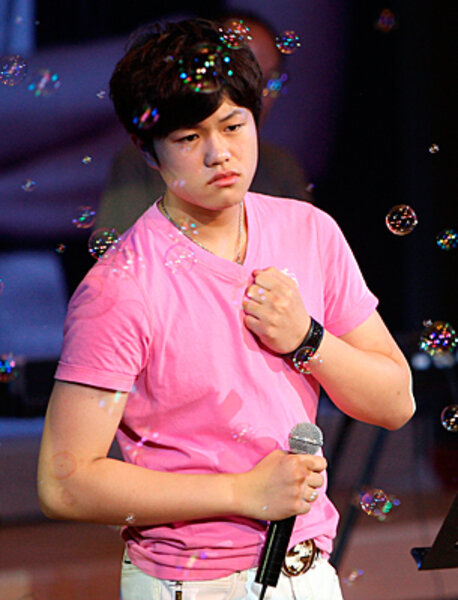

The teenaged son of a Chinese Army general and prominent singer has gone on trial for gang rape in Beijing, focusing further attention on the credibility of China’s legal system and sparking calls on the Internet for China's political elite to follow the rule of law.

Li Tianyi, who is accused of raping a girl along with four other men at a hotel in the Chinese capital in February, has denied the charge and reportedly says he was drunk during the incident.

China’s official media has lambasted the heavy attention given to the case, saying it bears no similarity to the corruption trail of former Party heavyweight Bo Xilai, his murderous wife, or henchman Chongqing police chief Wang Lijun.

Because of his parents’ powerful positions, the younger Li has access to the wealth and privilege that has allowed the criminal behavior of many other young offenders to be swept under the rug. The bad, and often dangerously criminal, behavior of some of China’s “second-generation rich” has become a tremendous sore spot for the government, which is undergoing a makeover of sorts to distance the Communist Party from the type of corruption endemic here.

“In contrast to the Bo Xilai and Wang Lijun cases, which are closely connected with China's anti-corruption efforts, Li's case, by its very nature, is an ordinary criminal case,” the conservative Global Times newspaper wrote in an editorial referencing two ongoing high profile corruption cases against political elites. “What's more, considering that some of the suspects are minors, reports should remain low key.”

But for many Chinese, the cases are part of the same problem.

Mr. Li is the son of People’s Liberation Army General Li Shuangjiang and well known People's Liberation Army singer Meng Ge. And this is not his first brush with the law. The teen stoked anger two years ago when he and a friend reportedly attacked a Beijing couple in a road rage incident.

The criminal case against Li could offer some evidence that this new generation of Chinese leaders intends to toughen up on its progeny.

Liu Renwen, the director of criminal law research at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says scrutiny is important in cases like this. While many are quick to assume guilt when it comes to wealthy and powerful people accused of wrongdoing, he says people need to demand the legal system treat everyone the same.

“We should be careful to avoid people’s resentment of the rich and the powerful to cause another type of injustice,” says Mr. Liu. “Both celebrities and ordinary people should be treated the same under law; everyone is equal under law.”