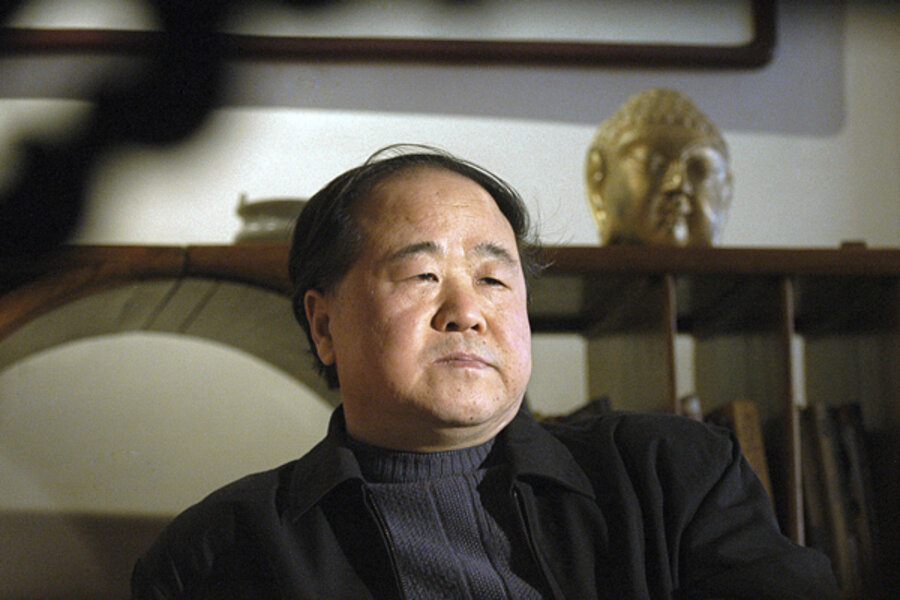

Mo Yan: Why the Swedish Academy awarded Mo Yan the Nobel Prize

| Beijing

Novelist Mo Yan, this year's Nobel Prize winner for literature, is practiced in the art of challenging the status quo without offending those who uphold it.

Mo, whose popular, sprawling, bawdy tales bring to life rural China, is the first Chinese winner of the literature prize who is not a critic of the authoritarian government. And Thursday's announcement by the Swedish Academy brought an explosion of pride across Chinese social media.

The state-run national broadcaster, China Central Television, reported the news moments later, and the official writers' association, of which Mo is a vice chairman, lauded the choice. But it also ignited renewed criticisms of Mo from other writers as too willing to serve or too timid to confront a government that heavily censors artists and authors, and punishes those who refuse to obey.

The reactions highlight the unusual position Mo holds in Chinese literature. He is a genuinely popular writer who is embraced by the Communist establishment but who also dares, within careful limits, to tackle controversial issues like forced abortion. His novel "The Garlic Ballads," which depicts a peasant uprising and official corruption, was banned.

"He's one of those people who's a bit of a sharp point for the Chinese officials, yet manages to keep his head above water," said his longtime U.S. translator, Howard Goldblatt of the University of Notre Dame. "That's a fine line to walk, as you can imagine."

Typical of his ability to skirt the censors' limitations, Mo had retreated from Beijing in recent days to the rural eastern village of Gaomi where he was raised and which is the backdrop for much of his work. He greeted the prize with characteristic low-key indifference.

"Whether getting it or not, I don't care," the 57-year-old Mo said in a telephone interview with CCTV from Gaomi. He said he goes to his childhood hometown every year around this time to read, write and visit his elderly father.

"I'll continue on the path I've been taking, feet on the ground, describing people's lives, describing people's emotions, writing from the standpoint of the ordinary people," said Mo, whose real name is Guan Moye and whose pen name "Mo Yan" means "don't speak." He chose the name while writing his first novel to remind himself to hold his tongue and stay out of trouble.

The state media hoopla and government cheer contrasted with the last Nobel prizes given to Chinese. Beijing disowned China-born French emigre dramatist, novelist and government critic Gao Xingjian when in 2000 he became the only other Chinese writer to win the literary prize.

After imprisoned democracy campaigner Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Peace Prize two years ago, the government heaped scorn on the award as a tool of the West and put diplomatic and economic relations with Norway, which awards the prize, into a chill.

Nobel winners have included political and social critics, including Guenter Grass of Germany and Orhan Pamuk of Turkey. The Swedish Academy disputed suggestions that it had selected Mo to seek Beijing's favor and rehabilitate the Nobel's image in the minds of many Chinese.

"As we've been trying to, naggingly, say: This is a literature prize that is awarded on literary merit alone. We don't take other things in consideration," said Peter Englund, the academy's permanent secretary. The reaction in a winner's homeland "doesn't enter into our calculus."

Mo writes of visceral pleasures and existential quandaries and tends to create vivid, mouthy characters. While his early work sticks to a straightforward narrative structure enlivened by vivid descriptions, raunchy humor and farce, his style has evolved, toying with different narrators and embracing a freewheeling style often described as "Chinese magical realism."

Among the works highlighted by the Nobel judges were "Red Sorghum" (1987) and "Big Breasts & Wide Hips" (2004), as well as "The Garlic Ballads." ''Frogs" (2009) looked at forced abortions and other coercive aspects of the government's policies restricting most families to one child.

His output has been prolific, which has contributed to his popularity and his impact. His works have been translated into English, Russian, French, German and many other languages, giving him an audience well beyond the Chinese-speaking world. Mo has a top literary agent, Andrew Wylie, who was at the Frankfurt book fair in Germany when he learned of Mo's Nobel and told The Associated Press: "We are in discussions globally." Several of his books quickly sold out Thursday on Amazon.com, although few copies likely were in stock.

Mo is probably best known to English-language readers for "Red Sorghum," thanks in part to Zhang Yimou's acclaimed film adaptation. The novel has sold nearly 50,000 copies in the U.S., according to the publisher Penguin Group (USA), a strong number for a translated work. Most of Mo's books in the U.S. have been released by Arcade Publishing, whose founder, the late Richard Seaver, had previously worked with Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller and other writers who faced battles with censors.

"Dick Seaver was Mo Yan's champion from the beginning and admired this exceptional writer's unique and original voice," Seaver's widow, Jeannette Seaver, said in a statement. "He was constantly reading passages to me."

Mo has said that censorship is a great spur to creativity.

"In our real life there might be some sharp or sensitive issues that (censors) do not wish to touch upon," he said in an interview with the literary magazine Granta earlier this year. "At such a juncture a writer can inject their own imagination to isolate them from the real world or maybe they can exaggerate the situation — making sure it is bold, vivid and has the signature of our real world."

Even so, Mo, who started writing while in the army, has steered clear from criticizing the government in public. He has been accused of refusing to appear with dissident writers at overseas literary seminars. The award stirred the criticisms anew.

"Some are opposed to his winning the Nobel Prize because he serves as a vice chair of the China Writers' Association and helps the government in censorship. But some are supportive, arguing literature should not be linked to politics but be valued on its own merit," said Murong Xuecun, the pen name of author Hao Qun, who has become more outspoken about censorship in recent years.

Yu Jie, an essayist and close friend of imprisoned Nobel laureate Liu who fled to the U.S. this year, was more acid. "This reflects the West's disregard for China's human rights problems. Mo Yan's win is not a victory for literature. It's a victory for the Communist Party," Yu said on his Twitter feed.

The government ignored the controversy and instead focused on the prize as emblematic of China's now recognized status as a great nation. "China is winning more and more respect from the world. We can say this award is not only for Mo Yan but to all the Chinese people," state-run television said in a commentary.

For many Chinese and his supporters, the award was welcome for recognizing an acclaimed author and for steering clear of past Nobel controversies.

"For me personally it's the realization of a dream I've had for years finally coming true. It's suddenly a reality," said Mo's publisher, Cao Yuanyong, deputy editor-in-chief of Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House. Cao said he and a dozen colleagues were toasting Mo in his absence with red wine in a Shanghai restaurant Thursday night. The prize is worth 8 million kronor, or about $1.2 million.

Born in 1955 to a farming family, his early education was cut short by the Cultural Revolution, a decade of political chaos when many of China's schools closed down. To escape rural poverty, he joined the army in 1976 and, while still a soldier, started writing in 1981.

His breakthrough came with "Red Sorghum." Set in a small village, it is an earthy tale of love and peasant struggles set against the backdrop of the anti-Japanese war. It was turned into a film that won the top prize at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1988. Amy Tan, author of the best-selling "The Joy Luck Club," became an early admirer.

Goldblatt, who has translated nine of Mo's books, remembered meeting the author in Beijing in the late 1990s, when the two had dinner.

"We didn't have any chemistry and we sat there, silent the whole time," Goldblatt said. "I tried to strike up a conversation and nothing happened. Then, he pulled out a cigarette, and although I had quit smoking, I said, 'Why not?' We were best friends from then on."

___

Nordstrom reported from Stockholm. Associated Press writers Didi Tang in Beijing and Hillel Italie in New York contributed to this report.