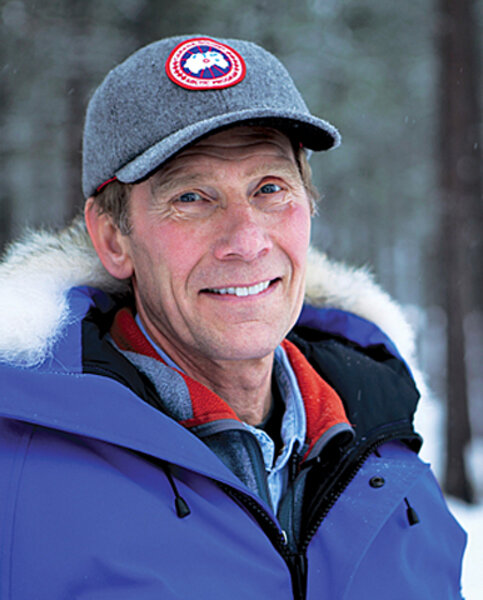

Steven Amstrup says it's not too late to save polar bears – and ourselves

Loading...

| Indianapolis

With apologies to "The Tipping Point" author Malcolm Gladwell, there is no tipping point – at least, not when it comes to global warming and sea ice.

Steven Amstrup, a senior scientist at Polar Bears International, has led a team of researchers that discovered that, contrary to expectations, even if all the sea ice in the Arctic disappeared, once the planet cooled back down, it would return.

"That was one of the great discoveries that allowed us to continue to instill hope in people that we could do something," Dr. Amstrup says. "Human nature is such that, if you think there's nothing you can do, you don't do anything. So this was a really important find."

That scientific discovery, published in 2010 in the journal Nature, is just one of the reasons that Amstrup was honored with this year's Indianapolis Prize, which is awarded every two years to a leader in the field of animal conservation. The winner receives $100,000 and the Lilly Medal.

The jury places great importance on the quality of the candidate's scientific research and on whether a species has a stronger potential to survive as a result of the work, explains Michael Crowther, chief executive officer of the Indianapolis Zoo, which administers the prize.

"In Steve's case, they were able to answer both requirements with great affirmation," he says. "On the back of the Lilly Medal … there is a quote from John Muir: 'When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.' The polar bear is one of the ultimate examples of a thing by itself" – but Amstrup has shown its connection to everything else.

Amstrup, a native of North Dakota, spent 30 years studying polar bears and their habitats as project leader for Polar Bear Research at the US Geological Survey's Alaska Science Center in Anchorage. In 2007, he led a different team of re-searchers that was able to get the bears listed as threatened on the US government's Endangered Species List – the only animal to date to be included because of causes related to global warming.

Earlier in his career, Amstrup solved the mystery of where female polar bears give birth. More than half of them dig their dens on ice floes to have their cubs, making the species vulnerable to climate change.

"His work on polar bear conservation is tremendously important, not only for polar bears but for the entire Arctic ecosystem, and for the multitude of species around the world that are now at risk from global warming," said Eric DeWeaver, program director of the Climate and Large-Scale Dynamics Program at the National Science Foundation, in a statement.

Along the way, Amstrup has camped on the ice (which, he says, gave him a taste – "just a smidgen" – of the conditions 19th-century explorers endured) and biked to work through Alaskan winters ("It's a little bit vigorous," he says.).

"I feel very lucky to have a career working on a species that really gets people's attention and has really captured the human imagination," Amstrup says.

He's been surprised by polar bears that wandered up to him while he was busy putting a radio collar or ear tag on another bear. Probably his most harrowing encounter, however, came in the early 2000s, when his team was doing research on bear dens and accidentally picked one that was occupied.

"We didn't find that out until my foot went through the roof of the lair, and I was just kind of dangling there up to my crotch in the snow, and I looked down and there was the female's head right next to my leg," Amstrup says. "I don't know why she didn't bite me. She looked at me with this really interesting gaze."

Amstrup quickly scrambled away. The bear emerged from her den and started to charge him and his assistant. "By then, the helicopter pilot got the helicopter started, and the engine noise scared her away," he says. "To this day, I certainly count my lucky stars."

In general, Amstrup finds the bears to be more curious and less bad-tempered than their grizzly cousins. A colleague, he says, calls polar bears "grizzlies on Valium."

"Each one has their own personality. They're not all the same – just like dogs and cats and humans," says Amstrup, who points out that some female polar bears will roam 230,000 square miles – a territory nearly the size of Texas – while others prefer to stay close to home, traveling less than 400 square miles.

"We have captured a number of young polar bears over the years, and some of them are just like a family pet and some are just chain saws with fur," he says.

Over the decades, as sea ice has retreated, Amstrup has observed behavioral changes, most notably polar bears showing up regularly where they had rarely been seen before.

"For example, on the north coast of Alaska, where I did most of my research, it used to be that seeing a polar bear on land was not very common. Now, there are polar bears all up and down the coast throughout the ice-free period," he says. "And it used to be that we didn't have an ice-free period."

That is, he says, perhaps the biggest change. "When I first went to Alaska, in the early 1980s, you could stand on the beach at the end of summer and see the ice. Now, it's 200 or 300 miles off shore, or more," Amstrup says. "It's a very different world than when I first went."

The speed at which changes are occurring in the Arctic makes it important for people to respond quickly, he says.

"The world is changing so fast. We need to act fast to change its direction. Time really is of the essence here. Even if you don't care about polar bears, we're talking about changes that affect all life on Earth," he says. "Polar bears just happen to be feeling it first because their habitat happens to literally melt when the temperature rises."

Every month or so, he says, someone writes to suggest putting giant floating pieces of styro-foam in the Arctic for the polar bears. While both are white and float, styrofoam isn't capable of sustaining the ecosystem of algae and bacteria that grows on the underside of the ice. It feeds the shrimp that feed the fish that feed the seals, which Amstrup calls "giant fat pills," a rich food source that has helped polar bears become the largest member of the bear family, with males weighing up to 1,500 pounds and measuring more than eight feet in length.

Then there are logistical issues: "Two weeks ago, we had lost as much sea ice as 35 times the size of Indiana. How much styrofoam can we make?" Amstrup asks.

However, he is hopeful that the world will react in time to save the polar bears.

"The problems that are facing polar bears are human-caused problems, and there are human-caused solutions," says Amstrup, who says he gave up his focus on research to share his 30 years' worth of study with the public. "We know the answer to what it takes to save them."

To change course will require people to change the way they live to reduce usage of carbon-based fuels, he says, citing things such as having well-insulated homes, energy-efficient furnaces and vehicles, and supporting businesses that engage in sustainable practices.

The biggest step, he says, is to find policymakers at all levels of government willing to entertain changes to people's throwaway lifestyle. "The critical thing is that polar bear conservation can't occur in the Arctic," he says.

Amstrup and his wife are building an energy-efficient home in northeast Washington, where they will grow their own fruits and vegetables. He also plans to hunt white-tailed deer and turkeys for food. Some of his prize money will go toward solar panels for their home and to replace their aging pickup trucks with fuel-efficient vehicles.

"Global warming is really the ultimate nonsustainable activity," Amstrup says. "Even if you don't care about polar bears, if you care about your own future, I think it's important to do what you can [to halt climate change]."

Helping wildlife

UniversalGiving (www.universalgiving.org) helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Below are three opportunities to help wildlife, selected by UniversalGiving:

• The sea turtle program at Osa Conservation works to guarantee the survival of turtles nesting on the Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica. Project: Support the sea turtle conservation program.

• The GVN Foundation offers opportunities to work with wild animals in captivity through a partner organization in Thailand. Project: Volunteer in Thailand.

• Defense of Animals-Africa provides sanctuary for chimpanzees orphaned by the illegal bushmeat trade in Cameroon. Project: Sponsor an orphaned chimpanzee.

• Sign up to receive a weekly selection of practical and inspiring Change Agent articles by clicking here.