F.K. Day, United States

Life in rural Zambia has improved dramatically for dairy farmer Cecil Hankambe. He has doubled his milk sales, purchased a farm, and earned enough money to send his children to school. He still milks the same cow and travels the same rugged roads to the local dairy co-op. The only difference now: Instead of lugging a heavy jug on foot, he pedals a bicycle.

Mr. Hankambe rides a Buffalo, a bike so sturdy and basic that its steel frame can carry up to 220 pounds and be repaired with a rock. Instead of delivering only seven to 10 liters of milk a day, Hankambe can now transport 15 to 20 liters to a chilling station before it spoils, boosting his profit.

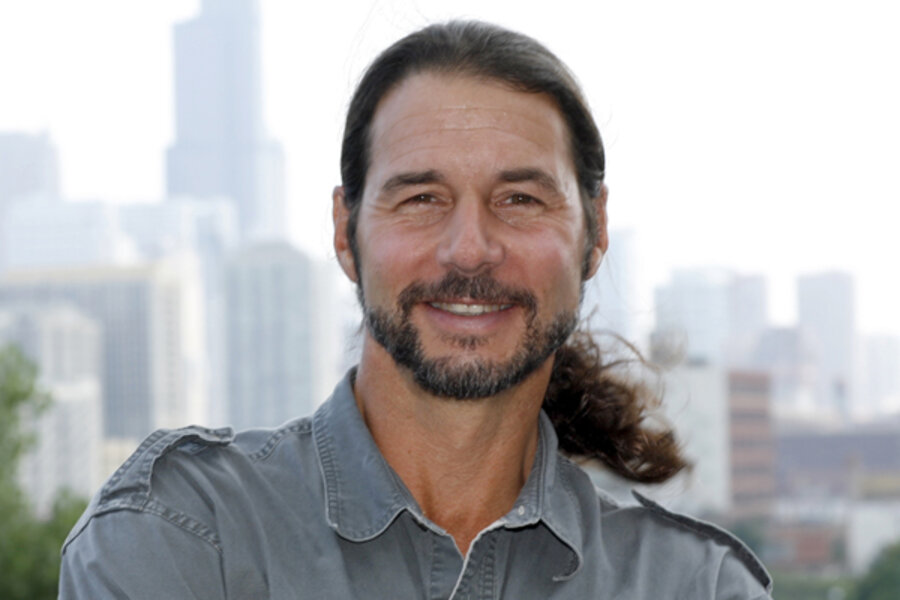

"A reliable bike can create reliability in a dairy farmer's income," says F.K. Day, founder of World Bicycle Relief, a foundation based in Chicago that produces the Buffalo and provides two-wheeled aid to people in developing nations. "You forget how important transportation is."

Mr. Day cringes at the word "philanthropist," even though his nonprofit group since 2005 has raised more than $13.5 million, distributed 116,000 bicycles at $134 each across 11 countries in Africa, and trained more than 800 bicycle mechanics.

"There is not a greater gift that one can give a community than an economic engine," says Day. "An industrial revolution on a personal level can push someone's productivity forward and help them to help their families and communities."

Before you think of Day as an enterprising industrialist who has arrived on the African continent to build a bicycle empire, let's back up. As a teenager, he flew – on his own initiative – from Chicago to Brazil to knock on the door of Irish priests who were building schools in São Paulo's poorest neighborhoods. They hadn't responded to his letters. But when he showed up on their doorstep, they had no choice but to put him to work.

That experience laid the groundwork for what followed three decades later. On Dec. 26, 2004, horrific images of tsunami-swept Southeast Asia flickered on TV screens in the United States. Day, now a successful cofounder of SRAM, an elite bicycle-parts manufacturer, wanted to do more than just fund relief efforts. "We thought we could leverage our expertise in the bike industry and offer that as aid instead," says Day.

So he and his wife, Leah, boarded a plane to Sri Lanka. Within weeks, Day had partnered with World Vision; he eventually oversaw the distribution of 24,000 bicycles that gave thousands of people affected by the tsunami the ability to reach their jobs, schools, and health-care centers.

From that experience, Day built his own model for a sustainable philanthropy, spoke by spoke, and World Bicycle Relief hit the road. Since 2005, its core strategy has remained simple: Provide transportation in the wake of disasters, help health-care workers visit more clients, make it easier for rural schoolchildren (particularly girls) to reach distant classrooms, increase the amount of goods people transport to market.

"We're not imposing, 'Here, have this tool. We will change your life,' " says Leah of the bike recipients. "[Bicycles are] a tool to help the life they are already leading, to quantify what they are already doing."

World Bicycle Relief now partners with groups (which buy Buffalo bikes to distribute through aid and microfinance programs) in Zambia, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Angola, South Africa, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. Day, who makes several field trips to Africa a year, says there is no replacement for hands-on experience. A nine-day Africa Rides program invites donors to Lusaka, Zambia, to build their own bikes and then ride with local recipients to rural schools and markets.

"If you can enter something new, open and honestly with beginner's eyes, something good is bound to happen," says Day.