Iraq election: Young war generation yearns for old stability

Loading...

| Fallujah and Baghdad, Iraq

Radio host Shahad Abdul Kareem, the rhinestones on her T-shirt and sequined headband sparkling, sits in the semidarkness of the Voice of Fallujah studio waiting for the generator to kick in so she can reach out to young listeners and find out what's on their minds.

In the run-up to the most important parliamentary elections since the fall of Saddam Hussein, members of this generation of first-time voters are not so much preoccupied with politics as with the difficulties of day-to-day life. Day after day, they pour out their miseries over Fallujah's airwaves.

"The first thing they mention is frustration," says Ms. Abdul Kareem, 25, whose name is an on-air pseudonym. The frustration stems from lack of jobs and lack of security. The second is the financial situation. One recent caller was a 32-year-old engineer who couldn't get married. Another was a young woman who hadn't been able to bathe for a week because there was never enough electricity to heat the water for everyone in the house.

"For us as Iraqi youth, we haven't seen anything nice in our life," says Abdul Kareem, who describes seeing shrapnel fly through her home before the battle for Fallujah.

Fallujah, west of Baghdad, was leveled in 2004 when US and Iraqi troops went into Al Qaeda strongholds. For the US, it was the fiercest urban fighting since the Vietnam War. For families, and teachers, and shopkeepers and their children, it was a nightmare. Whether disaffected Sunnis like those in Fallujah turn out to vote in March is key to the election's credibility and, eventually, to whether the country will hold together.

"I don't want to be too ambitious because I'm afraid that, if my ambitions don't turn out, I will be hugely disappointed," says Abdul Kareem.

Asked what she would dream of if she dared to, her guarded manner slips for a moment. "Many things," she says with a broad smile. "I wish I could continue my studies and get a degree, I wish I could travel. I wish it was like it was before, when I could go out with my friends and feel safe."

"Before" was the 1990s – the Saddam era, a time that many remember as almost idyllic in its safety. Unless their own families were victims of Saddam's terror, in between the 1991 war and the 2003 invasion, the streets of Iraq held almost no threats. Young women could go out to visit their friends in the evening, families dined at outdoor restaurants until after midnight, parks were full, life seemed less precarious

In many ways, what young Iraqis want from their leaders mirrors what any Iraqi adult wants – electricity, water, security, and jobs. Those were the most basic of expectations set up after the fall of Saddam and, seven years later, they remain largely unfulfilled. For most, democracy runs far behind.

"What did we gain from the first elections?" asks Ali Khutiar Abbas, at 19 already a father of three living in Baghdad's predominantly Shiite Sadr City. "We don't have jobs, we haven't seen any change in the security situation. I won't vote for anyone – I don't believe in elections anymore. This is our democracy," he says pointing to the overcrowded houses and teeming streets.

The eldest of seven brothers, Mr. Abbas has been working since he was 12 years old. He takes work whenever he can get it as a laborer and makes between $12 and $16 a day.

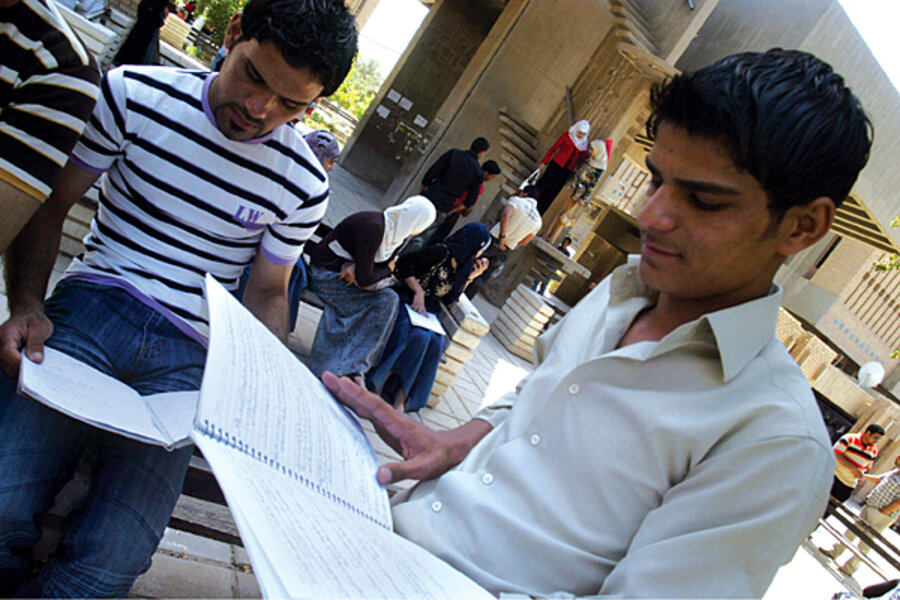

Almost 3 million Iraqis ages 18 to 22 will be eligible to vote for the first time in parliamentary elections. After cliff-hanging decisions on an election law, turmoil over the disqualification of candidates accused of Baathist ties, and a backdrop of election-related violence, Iraqis across the country will go to the polls on March 7.

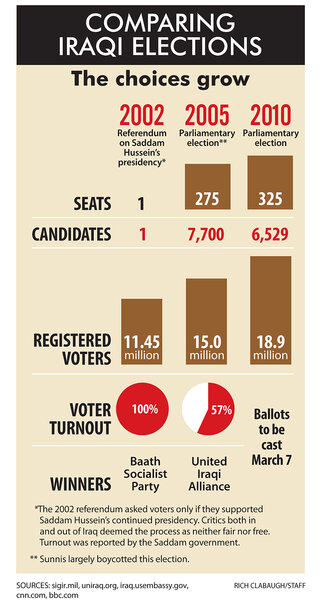

This is the first election held in a fully sovereign Iraq, after the United States relinquished control over security to the Iraqis last June. And it's the first national parliamentary election expected to include large numbers of Sunni Arabs – a major base of Baathist power under Saddam – who largely boycotted the 2005 vote. So it is seen as the first parliamentary vote that has a chance of electing a truly representative government.

* * *

This should be an exciting threshold to a new future for young people. But a broad range of interviews reveal that for this generation, born into a decade of trade sanctions and raised in war, there is an overriding sense of frustration, fears about security, and the struggle to find their place in a country still emerging from conflict.

"A lot of [young people] say, 'What would it matter if I did vote?' " says Adel Izzedine, director of the Voice of Fallujah. "They don't understand that their choice will define the future of this country."

There is concern that young, educated Iraqis will not vote; and that in the longer term, they will opt out of playing a role in remaking the country, says Abdul-Rizak Kathim, a sports professor at Baghdad University and a parliamentary candidate. His small party, Scientists and National Qualified Professionals, is campaigning on using Iraq's oil wealth and its technical competence to help rebuild Iraq and provide jobs for young people.

"Our mission now is to explain to young people that it's their national duty to go and vote and help write the future of Iraq," says Dr. Kathim.

Entering their teens when the war started, young people here have spent the past seven years surrounded by chaos and insecurity. It's difficult to find any young person who hasn't lost a relative to the war or the ongoing violence – which together have caused at least 30,000 deaths. Many young people in school or university have walked past bodies in the street to get to class or braved gunfire to take exams. The still-frequent explosions that close the roads are a regular excuse for being late.

With the fall of Saddam, they were left with a huge set of expectations that the government will be unlikely to fulfill.

"There are still kidnappings and bombs. Can we go out safely? We can't," says Nisreen Hamad, a physical education major at Baghdad University. "At 8 p.m. everyone is inside the house. If I'm home after 4:30, everyone says to me, 'Why are you late?' "

She intends to vote, but will take her cue about whom to vote for from her father, who seems to be leaning toward Prime Minister Maliki.

Widespread corruption has also fostered a cynicism about the political process that has persuaded many that it's not worth voting.

In the absence of family or tribal pressure to vote, many young people say they simply won't bother. Mr. Abbas, the teenage father in Baghdad's Sadr City, home to 2 million largely disadvantaged Shiites, doesn't plan to vote. The only reason he gets by, he says, is the government food rations still provided to every Iraqi – and even those are haphazardly come by.

Young Iraqis entering the job market have reason to worry. An Iraqi Youth Ministry survey, shows that more than half of young men between 25 and 30 are unemployed. In Saddam's time, young men were channeled, largely unwillingly, into the Army.

Now, "there are armies of jobless people," says Fawzi Akram, a Kirkuk member of parliament.

In a country with an insurgency fueled by alienation and economic necessity, that has dangerous repercussions.

"According to our figures ... 95 percent of the terrorists are uneducated and most of them are also jobless," says Mr. Akram.

Under Saddam, university students studied free of charge and were essentially guaranteed secure government jobs. Now, despite Iraq's oil wealth, government ministries are in a budget crisis and there is no large-scale private sector providing jobs.

It's a generation that has perhaps had it the hardest. The youngest were born in the era of sanctions that followed Saddam's 1991 invasion of Kuwait – a decade of severe shortages of medicine and even books; when private e-mail, satellite TV, and cellphones were banned; and when the West – particularly the US – was reviled.

While almost 60 percent of young people believe that terrorists are the main cause of instability, close to 35 percent believe the US occupation is a main reason, according to a survey of 6,500 young people conducted by the Iraqi youth ministry and the United Nations' World Population Fund.

Isolated from the world by 13 years of sanctions and seven more of warfare, this is the first Iraqi generation to undergo a technical revolution so vast it included not just the arrival of the Internet but of commercial television and mobile phones.

It's also a generation less well-educated than its parents, and it is increasingly conservative.

In the past five years, according to UN figures, the number of children in primary education has continued to decline. Girls, particularly, drop out in significant numbers with each subsequent school year. A chronically underfunded education system has led to what development experts consider unacceptably low school enrollment.

The decline in education contributes to ignorance about some key issues. The survey showed that the vast majority of young people believe those who are HIV positive should be isolated from the community. Fewer than 8 percent would share a meal with them. About half believe that the Internet is a bad social influence.

"The Iraqi situation in my opinion has moved to the right in the last five years, which means talking about these issues is more difficult," says Luay Shabaneh, of the World Population Fund.

In this country women have traditionally played strong roles in the workplace, but just a little over 50 percent of young people support women working.

Dr. Shabaneh says that despite the perceived differences between regions of Iraq, the survey released in January found education, job opportunities, and attitudes essentially uniform nationwide. He says that although the semiautonomous Iraqi Kurdistan, in the north, has a thriving economy, years of trade embargoes and inter-Kurdish fighting have held back development there.

"You cannot really distinguish the Kurdish youth from the rest of the country," he says. "Sulaymaniyah [in the north] is similar to Maysan [in the south]. It's truly Iraq.'

When it comes to voting though, in Iraqi Kurdistan, young people have helped fuel their own minirevolution. In regional elections in July, a new party challenging the established main Kurdish political blocs that have run the north of Iraq as a semiautonomous state for two decades captured a quarter of the vote, many of them from young voters weary of what they see as corruption and stagnation. In national elections though, Kurds are still expected to vote overwhelmingly for the two main established Kurdish political parties.

The parliament that the March vote will elect is seen as crucial in deciding the fate of areas long disputed between Kurds and Arabs.Despite trying times, there appears to be a residual optimism among a little over half of younger Iraqis. Of those Iraqis ages 15 to 24 surveyed, 57 percent are optimistic about the future. But that figure declines with age.

"When you look at the factual data – their work, unemployment, education ... you have one story, and when you look at the future, you have another story," says Shabaneh. "That is to say they haven't lost hope, which for me is an important message."

For many young Iraqis, though, it is an optimism tied to the hazy vision of the distant future rather than shorter-term expectations.

That lack of expectations fosters a cynicism that would normally be surprising in young people and is rooted in a feeling that their elected leaders have done nothing for them.

"The problem is that politicians aren't honest in their promises to young people," says Abbas Kathim al-Shimari, the deputy minister of youth. A move by some members of parliament to lower the minimum age for members of parliament from 35 to 30 has gotten little traction.

* * *

Security concerns – both financial and physical – are also causing this new generation to reconsider marriage.

"It's better to be single than to get married, because a year or two after they get married the men are either kidnapped or killed or arrested – even until now," says the Fallujah radio host Abdul Kareem, as she toys with the elaborate gold ring on her finger. "A girl gets married and has a child and her husband disappears from her life."

She readily lists examples: Her cousin's husband was killed last year, leaving her with three children. A friend's husband was killed in the 2004 battle for Fallujah – the friend then married her husband's brother, and last month he was kidnapped and is still missing. "She was married to him for a month," says Abdul Kareem.

Like most residents, Abdul Kareem's family fled the city during the battle in 2004. In 2005, they were worried about security, and her brother took the family's identification papers and voted for all of them – she wasn't sure for whom. They are still worried about safety in the coming election.

She hasn't examined the list of candidates. But if she were to vote, she would vote for someone from her province, Anbar, which includes some of the most prominent politicians recently banned from running for office. She believes the reason for the ban – alleged Baathist ties – are just excuses.

In the colleges, an alarming number of students see so little future here that they want to emigrate – a trend that government officials consider a crisis.

"Our young people are leaving the country and it's a very dangerous indicator – it means that basics for a good life are lacking here," says Dr. Shimari, the deputy youth minister.

Psychologist Layla Ahmed al-Noaimi, a professor at the University of Baghdad, says she was surprised by the survey's findings that only 17 percent of young people wanted to leave Iraq.

"A lot of the young people I talk to want to emigrate in any way possible – maybe more than 50 percent," she says. "They have no security, no work, no marriage – this is very difficult for young men."

Officials fear that the combination of overcrowding, lack of jobs, and sense of injustice is pushing young people to extremism or to the fringes of society in its drug underworld.

"Let us be frank," says Shimari, "the spirit of Iraqi youth is broken, and there is disillusionment and disappointment. Their confidence is shaken because of the wars, because of the pressures of threats. This needs our combined efforts."

Common wisdom has it that the scars of the war will take a generation to heal. For many young people here, it could well be the generation after this one.•