Egyptian regime, bracing for succession, secures near lock on parliament

Loading...

| Alexandria and Cairo, Egypt

Arriving at the dilapidated central train station in Alexandria, weary travelers are greeted by a wall of political campaign posters as they emerge into the exhaust fumes and crumbling glories of an ancient city once venerated as the world's premier seat of learning.

The posters urge a man who isn't on the ballot for parliament, and says he's not running for president in next year's election, to take the reins of the Arab world's largest country.

His name is Gamal Mubarak.

The investment banker turned politician is the son of and potential successor to President Hosni Mubarak, who has stood at Egypt's helm longer than any leader since the 19th century. But with Mubarak now 82 years old, Egypt – a country the United States relies on to advance its own agenda in the Middle East – is entering a fraught era of transition in which it appears to be shedding even the pretense of democratic progress.

In an exercise widely seen as a dress rehearsal for September 2011 presidential polls, Mubarak's ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) expanded its control of the legislature to a near monopoly in recent parliamentary elections, leaving the country's opposition groups in tatters.

Final results for the tightly controlled elections released this week showed the NDP winning 83 percent of the vote. But when parliament sits, various businessman and regional powerbrokers who ran as independents in search of immunity from prosecution and other perks of office are expected to join the NDP, which analysts say could push its share of parliament to close to 97 percent.

Outside analysts criticized the vote as the most fraudulent in decades and said it has defined a political system in which the 80 million citizens of the Arab world's largest country have no say in how they are ruled.

RELATED: Egypt election derided as less free than fraudulent 2005 vote

"This was unprecedented in Egypt. Embarrassingly blatant rigging. They've tried up until now to give a sense of competition and opposition involvement," says Shadi Hamid, research director at the Brookings Doha Center in Qatar. "I think it's fair to say this was one of the most rigged elections in Egyptian history, at least since 1952."

A move to secure all levers of power

The extent of the whitewash stunned outside observers, who had expected a token opposition to be allowed. The near elimination of independent voices from a parliament that in practice wields little real power signals that the regime is intent on securing all levers of power ahead of a possible presidential succession in the next parliament's term, they say.

Mr. Hamid, who was in Egypt tracking developments during the election, says the scale of the crackdown likely reflects a level of panic in the NDP and among regime powerbrokers. Though they seem from the outside to be a monolithic force, they appear to have emerging factions and differences of opinion over who should succeed Mubarak.

"There's some internal maneuvering going on, and we have to take the crackdown as a sign of fear and paranoia within the factions in the NDP," he says. "There is no agreement on a successor. This is the first time in a while that you don't know what's going to happen the next day. What happens when Mubarak dies? You don't know. And if you're the NDP, what you don't want is the opposition to have a strong place in parliament, [to] feel the wind is behind them, at this time of transition."

US in a bind

This leaves the US in a bind. Washington is unlikely to stop generous foreign aid to Egypt, which has averaged $2 billion annually, since it relies on Cairo to help keep Hamas weak in the Gaza Strip and to participate in containing Iran's nuclear ambitions.

But the United States, which under former President George W. Bush's administration championed greater democracy in the Middle East, appears stuck with a client that has an increasingly long list of human rights violations, an unwillingness to allow political reform, and great uncertainty about who will rule when Mubarak dies or steps down.

In a particularly notorious case this year, young businessman Khaled Said was beaten to death by what witnesses said were two policemen, who are now on trial. Their possible sentence? Three years.

"My brother begged for mercy, and a witness heard them say 'We've come to kill you,' " says Mr. Said's sister, Zahra Kassem. "There is almost no justice to be found in Egypt."

Near complete impunity – whether for powerful businessman or cops on the beat – is a consequence of a political system that allows for no feedback between rulers and the ruled, say Egyptian activists. "The whole point is that there's no accountability for anyone with the system," says Egyptian human rights activist Aida Seif el-Dawla.

"We are speaking about a semi-totalitarian regime," says Emad Gad, an analyst at the semiofficial Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies. "The era of talk about democratic reform is over."

American risks

The US is unlikely to reconfigure the relationship in light of this election. The White House issued a brief statement that it was "dismayed" by reports of fraud, but is unlikely to cut off Egyptian aid or generally warm ties as a result. But that, too, holds risks for American interests, says Hamid at Brookings.

"To go so far away from even a semblance of credibility, that suggests a certain level of disrespect [to America's democracy rhetoric] that we haven't seen in a while, and I think they're playing with fire," he says. "The US is not likely to put serious pressure on the regime; they almost never have, but you don't want to press your luck. Egypt is really pushing the boundaries here."

Hamid says that the situation is becoming more fraught and unpredictable.

"It's a game of Russian roulette that everyone is playing. People are saying Egypt will remain predictable," he says. "Well, people were saying in '78 and '79 that Iran was an island of stability.... Egypt's been on the brink of change for a very long time. I don't know when that's going to be and no one does. But it's going to come."

The fig leaf of democratic process used by the government in the past to argue that Egypt is not in fact an autocracy was, in many observers' eyes, removed from the recent parliamentary election.

Brotherhood out

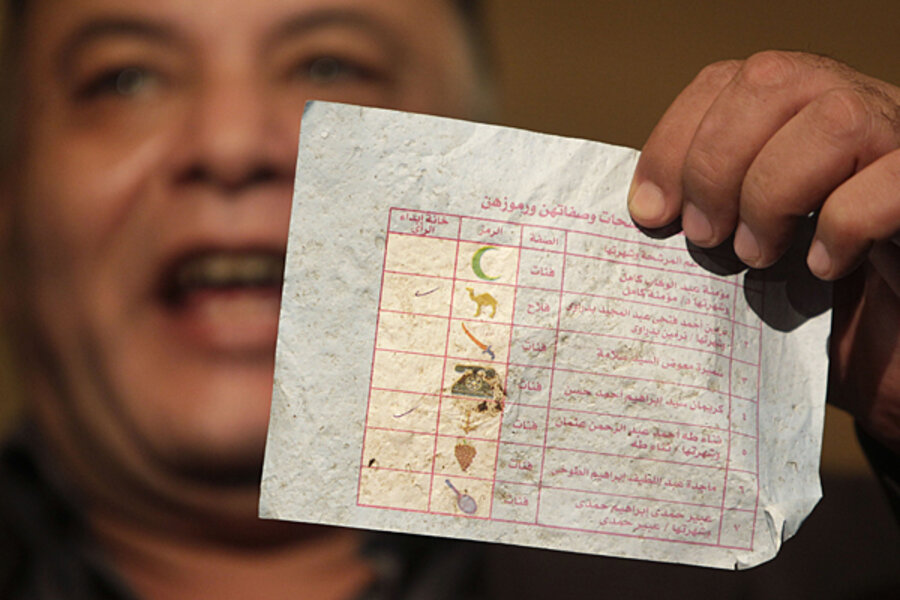

The first round of the vote, held Nov. 28, decided 221 of 508 contested seats. Ninety-five percent of those went to the NDP, while the popular Muslim Brotherhood was shut out.

In the last parliamentary elections five years ago, the Brothers – an officially banned Islamist movement that runs candidates as independents – tripled their number of seats, gaining 20 percent control of the legislature. This year, after the first round on Nov. 28, they had none.

The results and attendant allegations of fraud led to a boycott of the Dec. 5 runoff by both the Brothers and the Wafd Party, a secular group that won a handful of seats in the first round, ensuring a virtual NDP lock on the legislature.

Outgoing parliamentarian Mohamed el-Biltagy says the movement will work with other reformists in Egypt. "We will arrange with the other national groups to plan for reform and change – the goals are clear," he says. "We're all now on the same page regarding democracy."

Senior Brotherhood member Essam el- Erian says "violence is not an option" for the movement as it pursues its political goals, which have at their core the movement's old slogan "Islam is the solution."

As for popular unrest, Mr. Gad at Al- Ahram says it is unlikely, unless Mubarak decides to install his son Gamal as president in next year's elections.

"If Mubarak chooses to continue in power, then perhaps I cannot predict any tough troubles," he says. "But if he chooses to stay away and let Gamal run for this election, I think Egypt can go through very tough troubles."