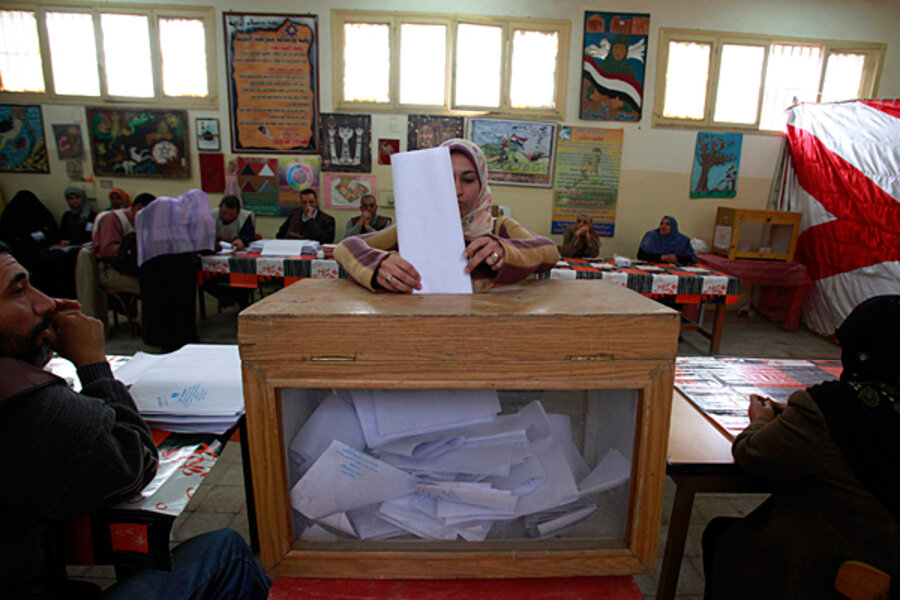

In Egypt elections, secular parties rally to stop Islamist tide

| Suez, Egypt

As Egyptians go to the polls in the second round of parliamentary elections, secular parties are fighting with renewed energy for a place in parliament after the overwhelming victory of better-organized Islamist parties in the first round.

They’re putting into practice lessons learned in the first round, in which Islamist parties took more than two-thirds of the vote. They've stepped up on-the-ground campaigning and increased coordination between Egypt's secular-leaning factions. Here in Suez, a small port city with a host of economic concerns, candidates for an alliance of secular parties known as the Egyptian Bloc have been on a new and punishing schedule of campaigning for the past two weeks.

The candidate at the top of the alliance’s list, Emad Khater Wassily, has been on the road by 6 a.m. each day, visiting factories and companies and meeting workers. From nine to noon, he meets with government employees. At night, he’s on the streets, shaking hands.

Mr. Wassily, a lawyer in Suez, says the party learned a lot from the first round. “The most important lesson was the importance of being on the ground, connecting with people, and building a base on the ground. We’ve also learned the importance of doing that until the last day,” he says in a rare moment of rest, after a ban on campaigning kicked in for the 48 hours before polling stations open.

The efforts of Wassily's party are critical, because secular and liberal groups are expected to have more difficulties in the second and third rounds of the staggered election since the first round included the areas where their base is strongest. Now the voting has moved to more rural and conservative areas, where Islamist parties are often familiar faces for their social welfare programs, and government neglect is rampant. At stake is not just parliamentary seats, but a say in how Egypt’s new constitution is written next year.

Suez, a relatively small governorate with only 389,000 registered voters compared to twice that number in Cairo’s central district alone, is an optimal place for grass-roots campaigning. The small city that sits near the southern end of the Suez Canal was a flashpoint of protest during the revolution that was met with an extraordinarily violent police crackdown.

Police are still nearly nonexistent on the streets, after their headquarters was torched during the uprising. Residents say security is a problem, as well as high unemployment, a housing shortage, and government corruption that allows the many factories and industry in Suez to avoid pollution regulations. Despite the vast revenue the Suez canal provides for Egypt, the city of Suez receives little in the way of employment or government investment. Campaign posters flutter from nearly every available space, speaking to the hot competition to be decided in voting today and tomorrow.

Uphill battle

The secular parties face an uphill battle. Many of them, including the two largest parties in the Egyptian Bloc, were officially established this summer. Though the Muslim Brotherhood founded its Freedom and Justice Party only this year, the organization itself has been around for 80 years, building a grass-roots movement through social welfare programs and religious outreach. Salafis, who follow an ultraconservative strain of Islam and won about a quarter of the votes in the first round, most for the al-Nour Party, have developed followings through decades of preaching in mosques. Both groups are well-funded, and put forth a strong challenge in Suez.

Liberal parties were criticized for weak outreach in the first round, relying too heavily on banners and television ads and leaving the street campaigning to the Brotherhood and Nour. In Suez, the Free Egyptians Party has taken that criticism to heart. Ramy Yaacoub, a senior campaign strategist for the party, says the campaign staff in Suez worked in Cairo and Alexandria during the first round. They’ve combined their expertise in the small governorate, pushing a more on-the-ground approach since they arrived.

“In Cairo we had mass media and huge billboards and talked to community leaders. Now we have more talking to individuals, the voters themselves, while still trying to maintain contacts with [community leaders like] a group of physicians, or leadership of a community like the Sufis,” says Mr. Yaacoub. “Also we did not rely so heavily on printed advertising. We've been using more of a word-of-mouth campaign. Suez is a small governorate and small community and word travels fast in small communities.”

But rumors travel fast, too. Many parties have accused the Free Egyptians Party, which was founded by billionaire Christian Naguib Sawiris, of being anti-Islam. In Suez, the party has worked to quell rumors that it wants to ban women from wearing the veil, or that it supports pornography. In an interview in the headquarters of the Suez branch of the Freedom and Justice Party, local FJP head Ahmed Mahmoud accuses local Christian churches of campaigning for the Egyptian Bloc. “The main numbers they have are because the church told their members to vote,” he says.

Sheikh Tarek Yassin El Refai angrily denies such accusations. Two days before the polling stations open, the leader of one of the largest Sufi orders in Egypt and member of the Free Egyptian Party’s political office, was in Suez to campaign for the party. There are about 10,000 voters there who follow Sufism, a more mystic strain of Islam.

Taking one for the team

The previous week, Mr. Refai withdrew as a candidate in Giza, across the Nile from Cairo, to support a secular candidate from the El Adl party. Others from secular and liberal parties have done the same in an attempt to consolidate votes and win the highest number of parliamentary seats for non-Islamist candidates in the second and third rounds of voting.

But even with their coordination and increased presence on the ground, the Egyptian Bloc and other liberal and secular parties will struggle. Sitting in a café on a main road in Suez, student Hany Mohamed say he’s voting for the Egyptian Bloc, but he expects the FJP to dominate.“They are strong here in Suez,” he says of the Brotherhood’s party.

Down the street, on which nearly every party has a tent that fills up with people at night, Ashraf Aly, an accountant in an oil company, drinks coffee in the chilly sea breeze. He says he’s studied the platforms of each party, and the FJP has the experience needed to make Egypt better.

“They are the ones who have been here for a long time. They gained a lot of experience during the time of Sadat and Mubarak and Nasser,” he says, referring to Egypt's last three leaders.

Of the Egyptian Alliance, he says, “I don’t know what their goals are. But all that I have heard from them is attacking the Nour Party and the Freedom and Justice Party.”