How one of Israel's worst schools rocketed to the top

Loading...

| Beit Jann, Israel

Beit Jann, with its bright buildings and narrow roads nestled into the side of a mountain near Lebanon, is one of the highest villages in Israel. But its other distinctions have traditionally been less lofty: one of the poorest, rainiest, and – until recently – least educated villages in the country, populated by Israel's Druze minority.

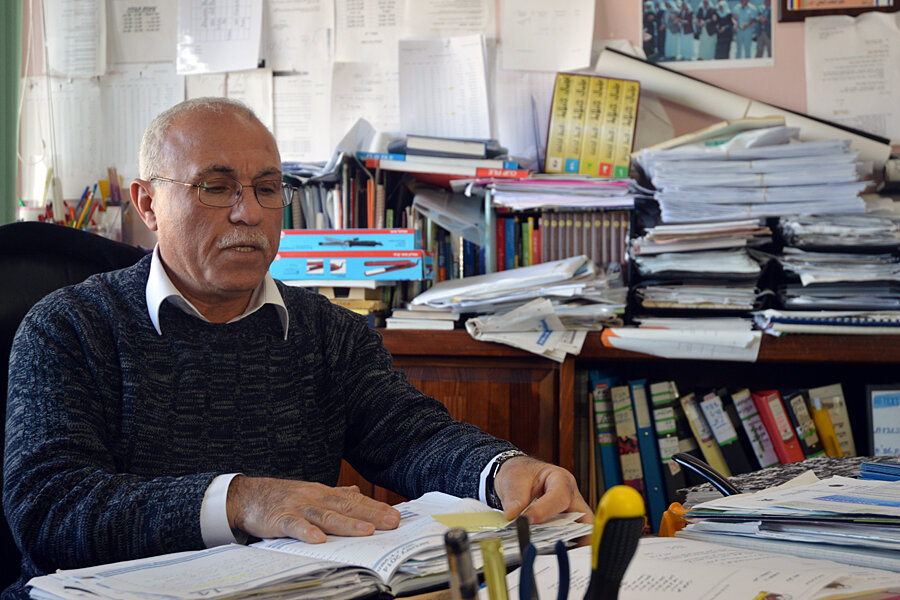

When Principal Ali Salalha took over in 2000, he was determined to change that.

“At the beginning, I decided I want to be like my village, on the top. How can I do that?” he recalls asking himself. “I and my teachers took a strategic decision – we want to be the best and nicest and most successful school in Israel.”

It was an ambitious goal. The first year, when Mr. Salalha cracked down on cheating, only 12 percent of high school seniors passed the Bagrut exam required for college admission.

Angry students slashed the tires of his car, but he pressed on. The test rates began rising. Five years ago, Yuvalim, a nonprofit founded in 2003 by hi-tech entrepreneur Eilon Tirosh, began working in the middle school, offering everything from math tutoring to lab work at a local college to rappelling down the school's walls.

Their combined efforts have paid off. Last year, the Beit Jann Comprehensive School registered a 100 percent pass rate on the Bagrut. While the town’s overall score was lower due to local students who chose to study elsewhere, the village still ranked third nationwide – topped only by two affluent Jewish communities in prosperous central Israel.

Mr. Tirosh spends about one day a week personally working on projects for Yuvalim, which works with marginalized communities across Israel. He says he is one of a number of entrepreneurs bringing the creative energy of the "Start-Up Nation," as Israel is often known, to bear on social issues. Most of them focus on education and at-risk youths, including those in Israel's less-developed areas, some of which face a double disadvantage as predominantly minority communities like the Druze or Israeli Arabs.

The remarkable success story of Beit Jann's school illustrates the potential for Israel to harness the innovation that has driven a hi-tech boom and help bridge the country’s gaping social divides, ultimately resulting not only in better students but also stronger communities, more social equality, and greater economic potential.

“It’s very relevant to tell people not only the story of the 'Start-Up Nation' but also the creative energy that we have here,” says Tirosh. “I’m seeing this also in social arena – dozens of nonprofits based on innovative ideas.”

More than tests and textbooks

As Yuvalim’s local coordinator, Jannan Ibrahim, walks through the Beit Jann school courtyard on a recent afternoon, almost everyone she passes calls out her name or stops to chat with her.

When the elegantly dressed young woman eventually makes it to the entrance of the high school, she walks purposefully between the two large lions – symbols of strength and honor – up to the principal’s office. The walls are graced with Arabic calligraphy and beautiful murals, depicting idyllic scenes of village life, giving the school an almost museum-like atmosphere.

“I believe to have good achievements, you need to have a good physical environment,” says Salalha, once we settle into his office. “I brought a good painter here and I asked him to make a very nice place to give students to give honor for their school, and it works.”

He also draws on the Druze religion, as well as on Jewish, Christian, and Muslim teachings, to create a strong moral environment. Each day he presents the students with a proverb that emphasizes one of the many values he aims to instill, including curiosity, honesty, generosity, modesty, and responsibility.

“I want my students to love knowledge, to have a good heart,” he says.

That dovetails well with Yuvalim’s holistic approach, which focuses not only on boosting academic performance but also building character through extracurricular activities, community service, and mentoring.

In Beit Jann, those activities have included first-aid training, visits to a local college of art, and rappelling off the school walls. Students meet three times a week from 4 to 7 p.m., often working in small groups of four or five – a stark contrast from their regular classes, which can include as many as 40 students.

Yuvalim targets both the weakest students and the most gifted students in Beit Jann’s middle school – the two populations that the Ministry of Education is least able to help, says Orith Landau, who helped develop the model.

“When you help smart kids to go forward and help underachievers [catch up], you basically move the whole class,” says Ms. Landau, who shies away from giving Yuvalim total credit for Beit Jann’s success, but says the nonprofit helped instill a new standard of excellence. “I think we lit this willingness to become the best, to be able to become the best, to be able to think we can do that.”

Goal: A village of engineers

Essam Qeys, an articulate 12th-grader who graduated from Yuvalim’s Beit Jann program several years ago, is headed to one of Israel’s top universities, the Technion, to study electrical engineering.

Considered an outstanding student, he says the program helped not so much with his academics but his personal development.

“My main goal was to become an engineer, but after joining Yuvalim … [my goal is now] to help my community and to try to develop and to change the world,” says Essam, who is now tutoring younger Yuvalim participants in math and physics – a paid position, he notes. “This is important, too – we get a salary and our first step forward in independent life.”

Beit Jann, a town of about 10,000, is poorer than 80 percent of Israeli towns, but Principal Salalha says “poor and rich for me doesn’t mean to succeed.”

Now that he’s reached the 100 percent mark with the Bagrut exams, he’s determined to increase the number of students in his school who are qualified to pursue the highest level of university education in fields like engineering. Right now, he has about 70 students at such a level, but he wants 80, 90, or even 100.

While the Druze in Israel are a minority of 100,000 – about 1 percent of the population – the principal points out that Jewish people are a minority in the world but still have accomplished a lot.

“They make such big things and I can do the same,” says Salalha, who dreams of Arabs winning Nobel prizes not only for peacemaking but in the sciences. “I want that the Arab people, the Arab nations in the Middle East, give the world something good, not bad – not killing, not fighting, but working together and making good things.”