Briefing: What is the Islamic State In Iraq and the Levant (ISIS)?

Loading...

What is ISIS?

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) was born out of the ashes of Al Qaeda in Iraq, which was established after the US-led invasion in 2003 and ultimately broke with Al Qaeda’s core leadership in Pakistan. Its goal was to build a strict Islamic state based around Iraq’s Sunni-dominated Anbar Province.

The group failed in its objectives, but when Syria’s war broke out in 2011, hardened Iraqi fighters flowed into Syria and joined up with Syrians and other foreign fighters. What emerged was a group with a vision of a transnational caliphate in Syria and Iraq - at least for starters.

ISIS also developed a track record of extreme brutality. The group has been involved in prisoner executions, sectarian massacres, and cutting off the hands of Syrians for petty offenses in areas it controls. ISIS has fought for control of Sunni Arab areas in Syria against other jihadi groups, including Jabhat al-Nusra (Nusra Front). What ISIS hasn’t done so far is seriously threaten the hold on power of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad.

How is ISIS getting its funding?

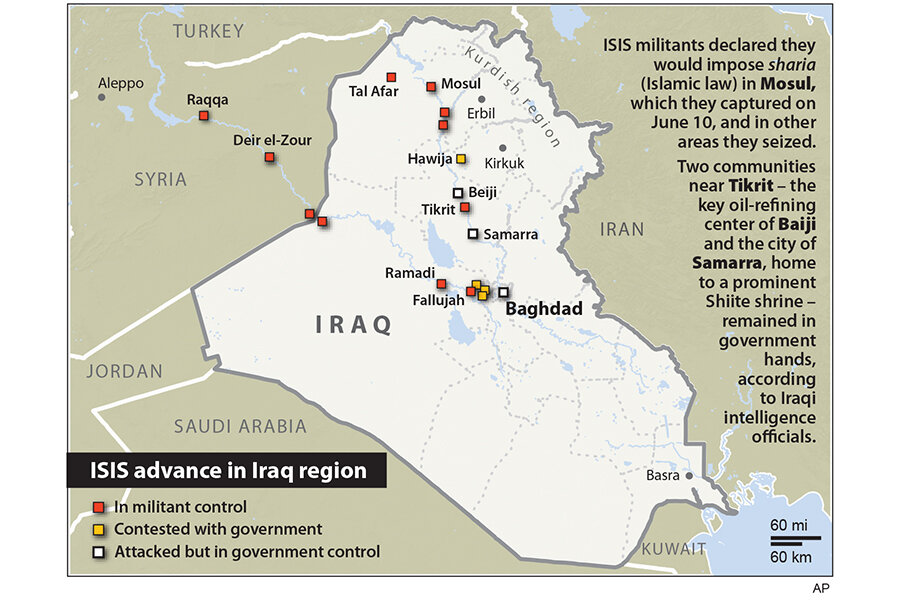

ISIS is presumed to have received funding from wealthy private donors in Sunni Gulf monarchies such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar, but for the most part, that money appears to have gone to rival jihadi groups. ISIS also generates its own income, having taken control of local businesses, taxing others, and making money from oil sales. The collapse of Iraqi security forces in northern Iraq in early June fattened ISIS’s coffers and its arsenal. Light weapons, artillery, tanks, Humvees, and other tools of war all fell into ISIS hands. The group allegedly looted more than $400 million in cash from banks in Mosul, which will strengthen its ability to recruit and pay fighters.

Who leads the group?

The nom de guerre of the leader of ISIS is Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi; his birth name is believed to be Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Sammarai. How important he is to military gains in Iraq, or to the group’s overall direction, is unclear.

Retired Col. Pat Lang, who formerly ran the Middle East desk at the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency, wrote on his blog that the advance of ISIS has been abetted by Iraqi Army officers who were dismissed shortly after the United States seized Baghdad in 2003. One identified by Iraqi officials is Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, a senior general under Saddam Hussein and the highest-ranking officer to escape capture after the US-led invasion. High-level military competence combined with the zeal of the jihadis is a potent mix.

But ISIS doesn’t appear interested in power sharing, or the Arab nationalism that drives many of the Iraqi Sunni fighters they now work with. If recent history is anything to go by, infighting is inevitable.

Is ISIS a threat to the US?

Its members hate America, want to impose their own views of sharia (Islamic law) on as much of the Arab world as they can, and are openly hostile to Western interests in the region. But they’re also focused on an insurgency in the region, and have not attempted anything like a terrorist attack on the US, Europe, or other parts of the Middle East.

Kenneth Pollack, a Middle East expert at the Saban Center at the Brookings Institution, argues that too much focus on ISIS in Iraq is a mistake. “Effectively the entire rogues’ gallery of Sunni militias from the 2006-2008 civil war have been revived by Prime Minister [Nouri al-]Maliki’s alienation of the Sunni Arab community since 2011,” he writes. ISIS is part of a broader coalition, and he argues against branding them “terrorists.”

“While I have no doubt that there are some among the Sunni militants who want to blow up American buildings and planes right now, and many others who would like to do so later, that is not their principal motivation,” Mr. Pollack writes.

ISIS is focused on its fight for territory in Iraq and Syria, and not the “far enemy” of Al Qaeda lore. Were they to consolidate something like a protostate, they might pursue terrorism down the line. But they’re a long way from that point.