Why ransomware is spreading, and how to guard against digital hijackers

Loading...

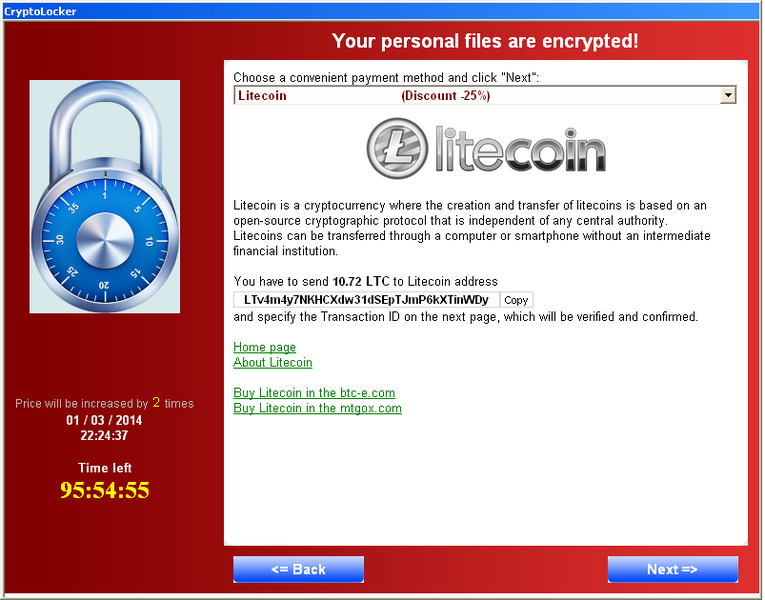

The first sign of trouble is usually a message like this: "All of your files were protected by a strong encryption ... . You will not be able to work with them, read them or see them, it is the same thing as losing them forever."

But that kind of alarming note – showing up more frequently on personal computer screens – does come with a remedy: "With our help you can restore them."

Security experts say that the scourge of ransomware, malware that seizes data until targets pay up within a certain time frame, is spreading fast. One of the most common varieties known as CryptoWall has hit at least 1 million victims and collected about $1.8 million in ransom, according to Dell Secureworks, the cybersecurity arm of Dell Inc.

And it's not just individuals that criminal hackers are targeting. The Chicago Tribune reported last week that a suburban Chicago police department paid $500 to regain data seized on department computers. The department was hit with a variety of ransomware known as Cryptoware.

Ransomware is a particularly vicious strain of malicious software, says Keith Jarvis, a senior security researcher with the Counter Threat Unit research team at Dell Secureworks.

“Most types of malware are stealthy and you have no idea you are infected. Ransomware is right in your face,” says Mr. Jarvis, a senior security researcher with the Counter Threat Unit research team at Dell Secureworks. "Some users don't have a choice. They need their files back."

Ransomware spreads in many of the same ways other malware makes its way onto computers: through corrupt e-mail attachments, malicious links in spam, website attacks, and harmful software that poses as advertising or hides behind Web ads. One common tactic: Spam disguised as fake shipping notifications.

The malicious software typically trawls through the hard drive and finds user documents, images, and other important files and encrypts them with a legitimate encryption key. The key is stored on a remote command-and-control server so the victim has no way to unlock the files without paying the ransom.

Experts say there are three major ransomware families operating globally. CrytoWall is perhaps the most well-known, and is controlled by a single criminal gang, says Jarvis. Victims span the globe. TorrentLocker, with victims mainly in Great Britain and Australia, is maintained by another group. CTB Locker, however, is available as a kit on underground forums, meaning anyone can purchase the code and set up a ransomware campaign. This has led to a recent increase in CTB Locker infections worldwide.

Prevention, while not perfect, is key to staying ahead of ransomware.

"By keeping your computer up-to-date you drastically cut the chances for any exploits to work because all known vulnerabilities have been patched," says Jerome Segura, a researcher with Malwarebytes, a software security firm.

Staying current with new software releases and updates ensures all malware including ransomware cannot exploit security holes in popular software such as Adobe Flash Player, Java, Silverlight, or Internet Explorer. Some experts recommend disabling scripts altogether in the Web browser or using browser add-ons to block Flash. Antivirus can't restore the encrypted files even if the malware is removed from the computer.

The FBI dismantled the well-known CryptoLocker variety of ransomware last June, giving some hope to users infected with that specific malware. Users who still have files locked by this particular ransomware can try using the tool on https://www.decryptcryptolocker.com/ jointly provided by FireEye and Fox-IT to try to recover their data. FireEye and Fox-IT offer this service because they recovered an attacker-controlled server with all the encryption keys used by CryptoLocker. The site works only for CryptoLocker infected files and would not be useful to unlock files locked by any other current ransomware family, Jarvis said.

Also, good data backup strategies can help, too. That can help users recover data without paying a ransom. That said, even regular backups aren’t enough as they need to be tested frequently to make sure the data is recoverable. In some instances, ransomware can lock files stored on cloud-based backup systems, too, if the user mapped the cloud service as a local drive.

And when backing up to an external hard drive, it's crucial to disconnect that device from the computer to ensure the ransomware can't see those files, say experts.

The effectiveness of ransomware also depends on the value of the infected device and the importance of locked data. Dell Secureworks calculated that less than 1 percent of victims actually paid to regain access to their files, and the average payment was about $655.

Those who do opt to pay still face challenges. Most ransomware requires victims to pay using bitcoin or other types of cryptocurrency. For many users, though, bitcoins are unfamiliar territory, one they have to learn how to navigate while the clock is ticking. It takes a few days to figure out the system, create an account, and fund it before the ransom can be transferred to the gang's account.

The longer it takes to pay, the ransom price tends to rise, says Jarvis. "And time is something victims don't have."