Chinese official: Train station attackers were trying to 'participate in jihad'

Loading...

A daily roundup of terrorism and security issues

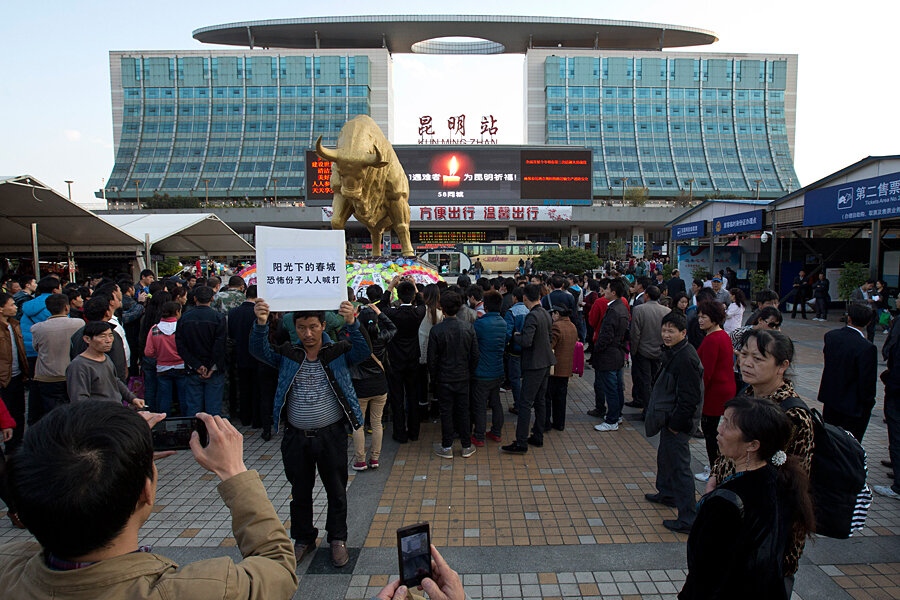

Chinese state media offered an explanation today for the train station attack that they’ve dubbed ‘China’s 9/11’: The attackers wanted to leave the country to participate in jihad, but lashed out in China instead when they were unable to do so.

“[They] originally wanted to participate in ‘jihad,’ ” Qin Guangrong, the Communist Party chief of Yunnan, the province where the incident occurred, told Xinhua and other state-run media, according to the South China Morning Post.

“They couldn’t get out [of] Yunnan so tried to get out in other places, but they also couldn’t leave Guangdong, so once again they returned to Yunnan.”

When the group failed to escape through southern Yunnan’s Honghe county – which borders Vietnam – they hatched the plan to target either the frontier area or Kunming’s transport terminals, the report quoted Qin as saying.

Earlier in the week, Chinese authorities blamed the incident on eight people from China’s restive Xinjiang Province in western China, four of whom were shot during the attack and four of whom were later captured, according to Reuters.

Beijing has long spoken out against what it says are militant Islamists from Xinjiang who want an independent state called East Turkestan. The province is home to most of China’s ethnic Uighurs, who are Muslim and have a different language and culture than the majority Han population.

But the response of authorities to the attack hints at their delicate balancing act.

Authorities blamed the attack on “separatist forces” from Xinjiang, and have vowed to respond aggressively. Today, Premier Li Keqiang vowed during his speech at the National People’s Congress that “we will firmly crack down on all violent crimes of terrorism,” and “we will ensure the safety of people’s lives and property.”

But officials have cautioned against “words or actions” that would inflame tensions, as they fear backlash over the attack could lead to a recurrence of clashes between Uighurs and ethnic Han Chinese that killed more than 200 people in 2009.

President Xi Jinping said yesterday that “we will build a ‘wall of bronze and iron’ for ethnic unity, social stability, and national unity,” according to Xinhua, who described his statements as “resolute opposition to any words and actions that damage the country’s ethnic unity.”

In a briefing on China’s Uighurs, the Monitor's Beijing bureau chief explained that “Beijing's fear of "splittists" undermining national unity is so deep that it is hard to imagine the authorities taking a more relaxed view of local customs, culture, and religion.”

Uighurs complain that the influx of Han settlers over the past 50 years has made them strangers in their own land, where they now make up less than half the population. Most of the good jobs created by economic growth go to Han, not to Uighurs who mainly do menial tasks. Uighurs fear that their culture is being stifled and their Muslim religious practice curtailed as the Chinese government fights to stamp out separatism; young men under age 18 are banned from mosques, for example, and essential school classes are taught in Mandarin, not Uighur. Economic development is all very well, a Uighur trader once told me, but it comes at a price: "They give us bread," he said, "but they take away our hearts."

Uighurs outside of Xinjiang have expressed concern that there will be backlash against them. Abdurehmen Kadir, the owner of a Xinjiang-style pancake restaurant in Dashuying, told The Wall Street Journal that he was afraid of a repeat of the 2009 clashes.

"I tell my people not to go out at night, and when they do go out, to be more careful," he said. "People had a bad impression of Xinjiang people before, they think we are pickpockets, thieves and dishonest."

Police have been careful not to inflame tensions in their searches in Kunming, the site of the attack, the Journal reported.

The officers were polite in questioning him, said Mr. Shawuti, a 48-year-old chef. Plainclothes officers returned Monday in force, swarming the predominantly Uighur neighborhood in an apparent search for suspects.

The carefully even-handed police response in Kunming's small Muslim enclave of Dashuying reflects the challenges facing Chinese authorities in confronting violence that is spilling beyond Xinjiang to the rest of China.

...

All that remained of the police presence in Dashuying on Tuesday were regular patrols by police cruisers and two black tactical squad vans parked at the main intersection in the neighborhood, a convergence of three narrow streets lined with mostly three- or four-story shophouses.

Even with the restrained police response, Mr. Shawuti and others in his neighborhood said they were concerned that resentment over the attack among Han Chinese, who make up a majority of China's population, might fester.