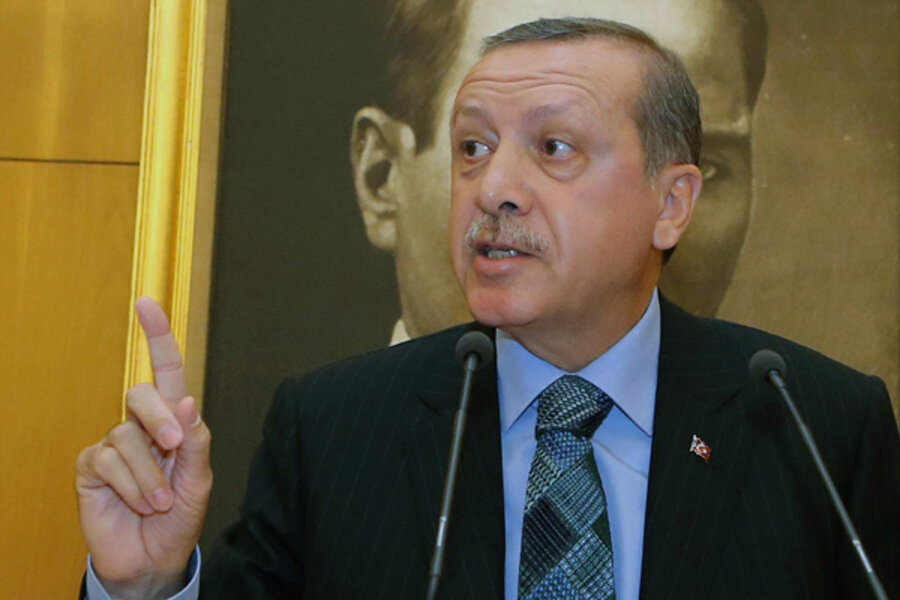

Turkey's Erdogan dismisses protests: 'What is the message?'

As his country experienced the fourth day of street protests against his administration, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan today dismissed the demonstrations, shrugging off comparisons to the Arab Spring and other movements that have shaken Turkey's Middle Eastern neighbors.

The Associated Press reports that Mr. Erdogan appeared "defensive and angry" when asked by reporters whether his government would soften its tone and whether it understood "the message" of the protesters opposed to what they say is the creeping Islamization of Turkey by his AKP party's government.

“What is the message? I want to hear it from you,” Erdogan retorted.

“What can a softened tone be like? Can you tell me?” he said. He spoke to reporters before leaving on what was planned to be a four-day trip to Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

He also waved off comparisons to the Arab Spring, saying “We already have a spring in Turkey,” alluding to the nation’s free elections. “But there are those who want to turn this spring into winter."

The comparisons come after a weekend of protests involving tens of thousands of demonstrators opposed to AKP policies that started last week in Istanbul's Taksim Square and spread to cities across the country. Though the protest initially stemmed from government plans to bulldoze Gezi Park, a small green square near Taksim, to build a shopping and luxury apartment complex, it exploded into a broader demonstration complete with running battles with police. More than 1,000 have been injured in the fighting since, reports Reuters.

Taksim's historical significance

Reuters also notes that Taksim holds a "particular resonance" for Turks.

While other Istanbul squares embody the grandeur of the Islamic Ottoman Empire, Taksim pays homage to the secular ideals of the republic founded in 1923 after the empire collapsed. More recently, the square was the site of a 1977 massacre of up to 40 leftists during a May Day rally.

"Taksim carries enormous significance for different circles ... To bulldoze Taksim without any real social consensus is to harm an important public space not just for Istanbul, but for all of Turkey," said Eyup Muhcu, head of the Chamber of Architects, in an interview before the protests.

The Christian Science Monitor's Scott Peterson reports that those in Taksim dislike the comparisons between their protests and the Arab Spring that felled regimes across the Middle East. "Those were distinctly Arab events, they say, while Turkey’s protest is about more inclusive democratic leadership," he writes.

“This is the radicalism of the moment,” Eda [a history student at Bogazici University] says, pointing to a nearby police car, where other students cavorted and took photos of themselves, as if on a new playground toy. “This is not the consensus. It’s just a show."

Similarly, the BBC's Paul Mason writes that despite the comparisons that some have drawn to recent protest movements around the world, the Taksim demonstrations are distinct.

I have covered Syntagma [Square anti-austerity protests in Greece], the Occupy protests and reported from Tahrir Square. This is different to all of them.

First, it is massive. The sheer numbers dwarf any single episode of civil unrest in Greece.

Second, the breadth of social support - within the urban enclave of Istanbul - is bigger than Greece and closer to Egypt.

But Mr. Mason also distinguishes it from Egypt.

Is this the Turkish Tahrir? Not unless the workers join in. Turkey has a large labor movement, and a big urban poor working population, and Monday is a work day, so we will see. It is certainly already something more than the Turkish version of Occupy.

Time Magazine writes that "For Erdogan, the greatest danger is that conservative Muslims, who form the AKP’s base, will flinch at the images of police brutality and begin to join the protesters’ ranks."

That may be one reason why the government has pulled police forces out of Taksim and clamped down on the media harder and more visibly than ever. Many press outlets are downplaying the protests. On Saturday, one of the country’s leading papers, owned the Prime Minister’s son-in-law, buried the story. Later that evening, as clashes between police and protesters continued around Istanbul and other cities, CNN Turk, a leading news network, aired a cooking show, plus documentaries about a 1970s novelist, dolphin training, and penguins.