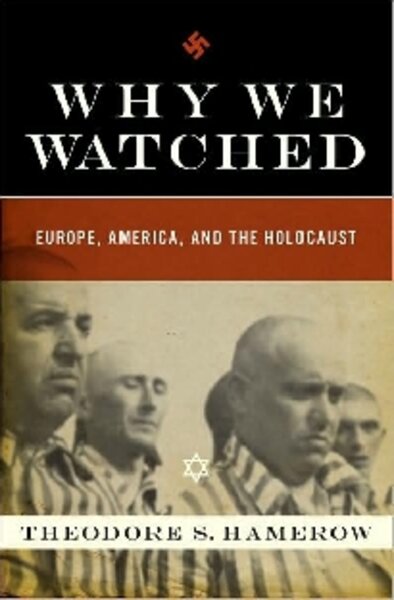

Why We Watched

Loading...

Any reader who pays attention to publishers’ offerings would be justified in exclaiming, “Oh no, not another book about the Holocaust!”

Historian Theodore Hamerow recognizes that reaction, so he opens his new book about the Holocaust by explaining his contribution to the subject. Nearly 500 pages later, I am persuaded that Why We Watched: Europe, America, and the Holocaust offers readers a vision that is indeed fresh – and worthy.

My decision to add one more book to the vast literature dealing with the destruction of European Jewry is a result, indirectly at least, of that very vastness,” writes Hamerow, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

He perceived a gap in the vast literature, a gap failing to explain adequately “why mass brutalities, accepted as almost understandable, almost predictable while they were occurring, began little by little to be perceived as unspeakable atrocities.”

A tour of world thought

To answer that question, Hamerow takes readers on an intellectual tour of the attitudes and events during the 1930s and 1940s anticipating the annihilation of the European Jews.

Hamerow sets out his book’s multistage deconstruction clearly and compellingly. “There must be a careful examination of the widespread belief, not only in the Old World but in the New, that society had to deal with something called the ‘Jewish question;’ ” he writes, “that this was a question that could not be ignored, that demanded a solution; that it was not clear what that solution should be, that there might in fact be several solutions; but that whatever the final solution was, a solution had to be found.”

German dictator Adolf Hitler was not alone in his belief that a substantial Jewish population needed to be undone, through banishment at the minimum, mass death at the maximum. Political and military leaders of many other nations shared this view, though none were as vocal as Hitler.

So did a number of relatively powerless citizens in other nations, who for reasons that defy comprehension, had demonized Jews in virulent, unique ways without ever coming to understand anything about the Jewish faith or its profound relationship to the teachings of Jesus.

Hamerow structures his book carefully. Because much of the information it contains has been dealt with elsewhere, it is the structure of the book and the way that he unfolds his arguments that become the secret of Hamerow’s success.

A history in four parts

Part One of the book is set primarily during the 1930s, as economic and political crises in Eastern Europe, Western Europe, South America, and North America (especially the Great Depression of the United States) give rise to a search for scapegoats.

Jews were already suspect because of their religious beliefs, “odd” customs, and easy-to-spot looks, and they ended up as the primary scapegoats in spite of (and partly because of) their small numbers.

As a result, when the atrocities of the Nazis began to spread, Jews in Germany and the other lands it had recently come to control found it difficult to find asylum in other countries.

Part Two of the book focuses on the United States, as its various power structures allowed anti-Semitism to rule public policymaking, despite an avowed abhorrence of Hitler’s final solution.

Part Three of the book examines the grinding down of the European Jewish population while so many of the world’s citizens either watched from afar or averted their eyes.

Part Four of the book explains the transformed state of world Jewry after World War II. Part of the transformation involved the acceptance – much too late – of the fact that Hitler’s final solution should have been alleviated by intervention from the World War II allies, especially the governments of the United States, Britain, and France.

Scholarly, with rich narrative

Although the book is built on a hypothesis and therefore is frequently theoretical, it succeeds in part because Hamerow indeed peoples it with characters, from the obvious choices of Hitler, Winston Churchill, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt to religious leaders and nearly anonymous individuals, Jewish and non-Jewish alike.

Another large part of the book’s success can be attributed to Hamerow’s writing style. Unlike most academic historians, he has mastered a conversational tone that never comes across as either condescending or stuffy.

Another excellent book about Jewry might appear in the future, assessing a world that no longer feels a need to grapple with a “Jewish question.” As Hamerow notes, the conflict over the Jewish question during the 20th century led to “vain hopes and failed aspirations.”

May the history of the 21st century “have a happier ending than the old one,” he writes.

Steve Weinberg’s newest book is “Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller,” published earlier this year.