Want to be a writer? You need a favorite author

Loading...

When I asked each student in my freshman-level college writing class to name a favorite writer, the responses proved diverse, including everyone from J.K. Rowling to Bill O’Reilly. I also got quite a few votes for Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, which raised my eyebrows.

(Either there’s a wave of transcendentalism among members of Generation Y, or some of my students had drawn a blank from my question and decided to pencil in a placeholder from their “Norton Anthology of American Literature.”)

I’ve seen writing students shrug when asked about their reading habits, presumably because they do little or no reading that isn’t assigned. But as I like to explain to any aspiring writer, writing without reading is a little like trying to excel at baseball but knowing nothing of Babe Ruth, or aiming for a life in the NFL without watching professional football. Just as athletes can improve their skills by watching sports heroes, writers can learn by finding a writing hero and following his work.

I make this analogy with some hesitation, since writers are not, in the ideal sense, supposed to be hero-worshipers. The best writing is driven by critical thinking, which is based on intellectual discipline, not giddy adulation.

But writing can be a lonely, dispiriting business, and it helps to have a role model or two who can hold your hand and remind you of what words can do when used by a true artist. This doesn’t mean that the literary great at the top of your favorites list should be embraced as an infallible icon. In fact, one of the great benefits of following a gifted writer is learning from his mistakes and limitations, too.

Life would be much easier if I could simply pair each of my students with an appropriate writing hero and send them on their way. But finding a hero, like finding a spouse or a best friend, is a mysterious process that seems more governed by luck than design. Perhaps all one can do is be open to opportunity when it strikes.

My own writing life changed dramatically in high school, when I came across an H.L. Mencken anthology at a neighborhood rummage sale. My classroom teachers had told me that writing was important and useful and potentially elevating, but in reading Mencken, the irascible journalist and critic who held sway in the 1920s, I discovered that writing could also be a great deal of fun. I quickly sought out his other books, delighting in sentences that popped like firecrackers. Mencken’s bombast – “It is the dull man who is always sure, and the sure man who is always dull” – seemed the perfect companion for a young writer feeling his oats.

In college, I found a strikingly different hero in E.B. White, whose essays fell into my hands during a stray hour in a bookshop before an afternoon matinee. White, whose prose was self-effacing and beautifully understated, was just the right complement to Mencken’s pyrotechnics, teaching me that a writer doesn’t always have to shout to be heard. A shelf of White’s books now sits next to Mencken’s in my library.

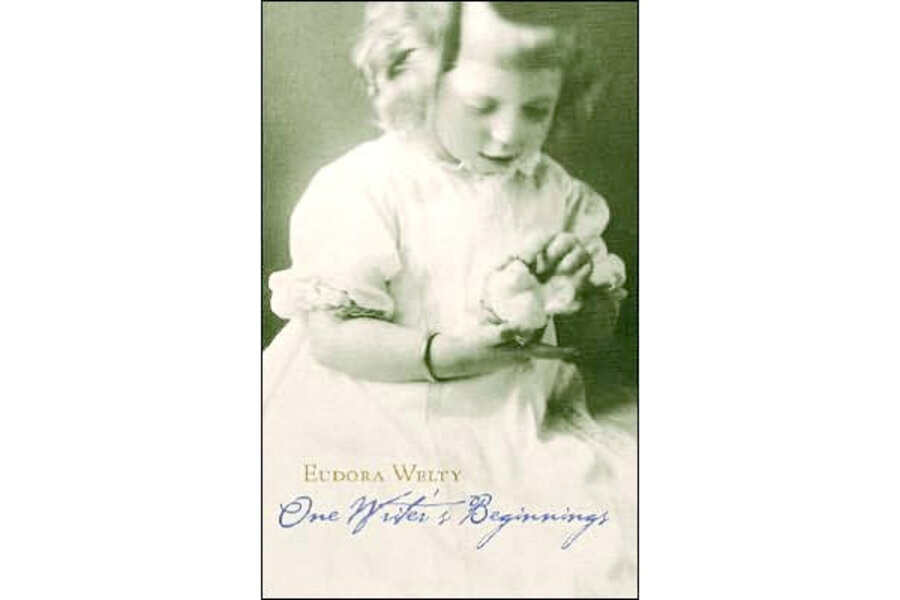

A couple of years later, an equally chance encounter with Eudora Welty’s memoir, “One Writer’s Beginnings,” yielded another lesson that’s deeply informed my writing life. Before Welty, I had thought of a writing career as a kind of extended road trip, with inspiration invariably tied to changes in locale. Welty, writing stories and essays of exquisite insight and grace from her native Jackson, Miss., affirmed the value of standing still. The conclusion of her memoir still rings in my ears: “As you have seen, I am a writer who came of a sheltered life. A sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within.”

I don’t know how I could have pursued a life in writing without my writing heroes, and I hope my students find a few for themselves. The trick, though, is to open a book, and read.

Danny Heitman, an author and a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is an adjunct professor at LSU’s Manship School of Mass Communication.