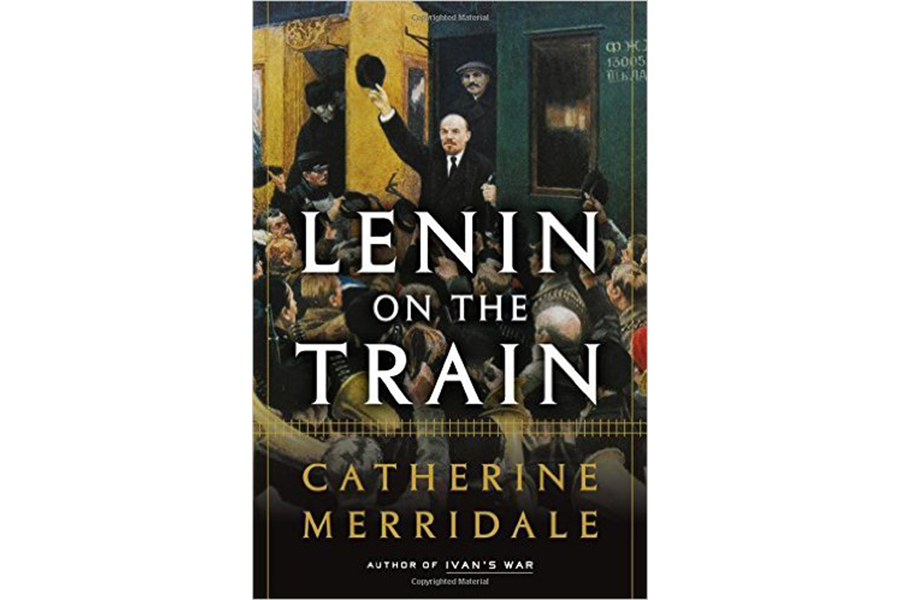

'Lenin on the Train,' chugging toward history

Loading...

Back in 1917, German officials figured a man named Vladimir Ilyich Lenin would be a handy tool to pull its enemy Russia out of World War I.

First, they'd help him get there on a train from exile in Switzerland. Then he'd convince the Russian populace to support peace. Next, they assumed, he'd be conveniently overthrown, and that would be the end of Lenin.

Everybody miscalculates sometimes, but this one was a whopper. "They didn’t expect him to reshape the politics of the whole planet in the process," says British historian Catherine Merridale, author of the new book Lenin on the Train. But, of course, he did just that.

As Merridale traveled the same route that Lenin took from Zurich to St. Petersburg (then Petrograd) a century ago, she found that he's faded somewhat into obscurity.

And yet, his train ride turned out one of the most consequential voyages of all time.

In a Monitor interview, Merridale talks about the trip, the war, and Lenin himself. "This man changed the course of global history," she says "Without him there would have been no Soviet Union and no Cold War. Marxism would have remained a 19th-century philosophy, not the theme-tune for one-third of the world’s new governments."

Q: What made you become interested in writing about Lenin and this time period?

I met Lenin for the first time in 1982 when I was on my first ever visit to Russia. I was a student, and I had the dubious pleasure of trooping into the mausoleum on Red Square and filing past the great man’s mummified corpse.

Lenin always remained a bit of an enigma, despite the fact that he was everywhere, if you count statues, paintings, busts, and medals as well as the man’s physical remains.

This year is the centenary of the Russian revolution, and I’ve taken the opportunity to settle my account with its most famous leader.

Q: What was Lenin doing in Switzerland and why did he want to go home at this time?

Lenin was in exile at the start of 1917. He’d left the Russian empire some years earlier – as a revolutionary against Tsarism he would otherwise have been thrown into jail – and had lived in several European cities, including London.

He was in the Austro-Hungarian empire when the First World War broke out, and as a Russian that made him an enemy alien. He was arrested when local police found a loaded gun among his books. It took a lot of string-pulling to get him released, and after that he really had to settle in a neutral country, which effectively meant Switzerland.

When the news of Russia’s first revolution reached him in March 1917 he was impatient to get home and play a full part in the country’s new, exciting politics.

Q: How did the Lenin project fit into Germany's war efforts?

Lenin appealed to the gentlemen of the German Foreign Ministry because he was a fanatic who could be guaranteed to fight for Russia’s exit from the war. The Germans also funded Finnish nationalists, Islamists, and a variety of different insurgent groups from the Baltic to the Caucasus.

The Germans used malcontents to stir up trouble in the British Empire too: There were schemes to support the Irish nationalists as well as funds for rebel groups in the Middle East and Persia.

Q: Why didn't the British try to stop him from getting to Russia where he'd try to push the nation out of the war?

London opted to let Lenin go after weighing the problem of offending Russian public opinion against the likelihood that this wretched Lenin person might cause a spot of local bother before the Russians arrested him themselves.

Q: Once he got to Russia, how did Lenin avoid crumbling under accusations that he was a tool of the Germans?

Before he even made it home, the right-wing press was accusing him of treachery. The calls for his arrest also began while he was still en route. Worse, the rumor spread that he was taking German money to finance his political campaign.

His critics never ceased to talk about his so-called German gold, but once he was in power there was not much they could do about it.

Q: What did you learn about what you call Lenin's "consuming, merciless cold fire"?

I knew about Lenin’s merciless political passion before I began this book. I’d read about the shootings and the enraged speeches, the way he never gave up on his cause.

But it was sobering to spend time with a man who literally thought about nothing but revolution. Lenin gave up almost every human pleasure – he stopped playing chess because it distracted him, he stopped listening to music because it made him sentimental. There really was no other project in his life.

Lenin’s only foible was politics. After spending two years in his company, I’m glad to say that people like that are rare.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is immediate past president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.