For ACA, a cautionary tale about rushing law changes through legislative short cut

Loading...

I intended to write a completely different post about how repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would undermine Medicare’s finances. My story was half right: repealing the 0.9 percent additional Medicare payroll tax on high-income taxpayers would cost the Medicare trust fund about $145 billion over the next decade, enough to accelerate the date of insolvency by a few years—to 2028 according to the latest Trustees Report.

But I was surprised to learn that repealing the “additional Medicare contribution”—a 3.8 percent levy on net investment income of high-income households that is projected to raise even more —would have no effect at all on the Medicare trust fund. That’s because the additional Medicare contribution doesn’t go in the Medicare trust fund.

Instead of a story about the future of Medicare, this turns out to be a cautionary tale about the dangers of rushing a major change in health and tax laws through a legislative short cut—one that may prove timely in the current debate over the ACA.

Section 1402 of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (part 2 of the Affordable Care Act) is titled the “unearned income Medicare contribution.” Commonly called the net investment income tax (NIIT), it is a 3.8 percent tax on investment income for households with modified adjusted gross income over $200,000 for singles and $250,000 for married couples. It is in the part of the Internal Revenue Code that stipulates payroll taxes to support Social Security and Medicare. But it’s just another tax.

When I discovered this anomaly, I queried policy experts about why the NIIT doesn’t help finance health care for seniors. A colleague speculated that maybe the revenue was originally intended to go into the Medicare trust fund until Congress needed the money to pay for other parts of the ACA, but that doesn’t really hold water. The federal budget is reported on a unified basis, meaning that revenues earmarked for a trust fund are considered like any others for purposes of revenue estimates and overall budget accounting (such as computing the Federal budget deficit).

What is clear is that in the crush of producing 1,000+ pages of healthcare legislation, the bill that passed the House somehow omitted the crucial sentence saying that there shall be an appropriation to the Medicare trust fund equal to the revenues collected from the NIIT.

In principle, this might have been fixed when the legislation got to the Senate, where a healthy majority (56-43) voted for the bill, but that wasn’t enough to redirect the revenues to the Medicare trust fund because the ACA was enacted as a “Budget Reconciliation” bill, subject to special rules. In particular, legislation considered as part of budget reconciliation is subject to the Byrd Rule, which makes “non-germane” amendments subject to a point of order.

If a Senator had proposed to amend the bill so that the NIIT revenues would be allocated to the Medicare Part A trust fund, any Senator could have objected that such an amendment would have no effect on the revenue raised under the bill (recall that trust fund revenues are treated the same as general revenues) and 41 senators could have voted down the amendment. When Senator Kennedy died and was replaced by Republican Scott Brown, the Democrats lost the super-majority necessary to overcome points of order. Thus, the Medicare investment income surtax does nothing to bolster Medicare’s finances.

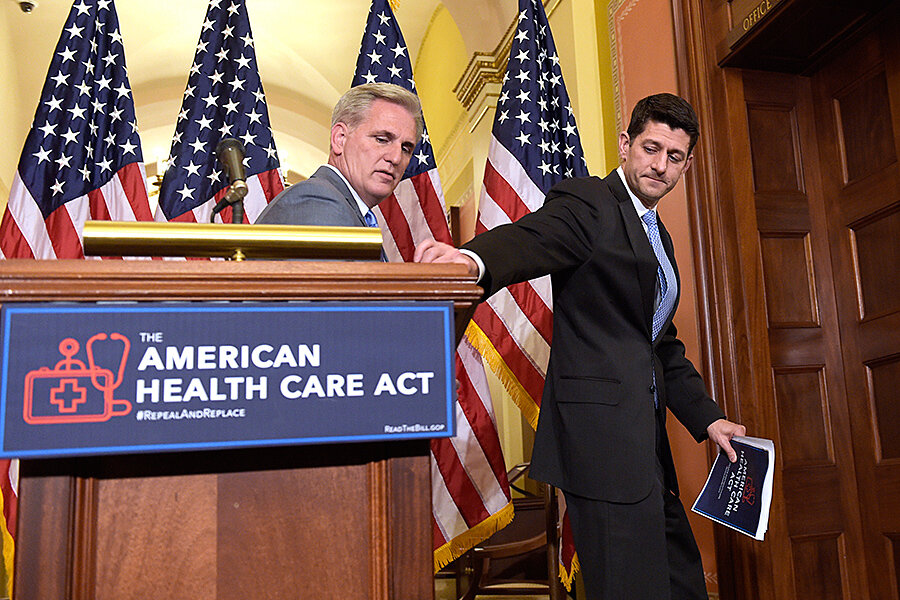

How is this relevant to today’s debate? Republicans are planning to repeal and replace the ACA as part of one reconciliation bill and then enact tax reform as part of a second bill. Few if any Democrats are likely to support either bill, meaning that any points of order are likely to be sustained. So GOP lawmakers might double and triple check their legislation before submitting it.

And, maybe, they should recall how precarious the ACA turned out to be given lack of even token bipartisan support. If Republicans want to enact lasting health care or tax legislation, they might consider the pros and cons of crafting bills that could win some support from the (current) minority party. Assuming that Democrats aren’t in full obstruct mode…

This story originally appeared on TaxVox.