- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- On Ohio ballot, a retired justice’s crusade to make politics competitive again

- Today’s news briefs

- Reframing a dictatorship: Argentine human rights museum under fire

- The Philippines has held out on legalizing divorce. Is it set to call it quits?

- College students voted in big numbers in 2020. A look at what 2024 might hold.

- Live, from New York, it’s the ‘SNL’ origin story ‘Saturday Night’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Picking the ‘true’ past

History gets recorded in layers. Good journalism provides an unadorned capture of events in real time. New facts bring reflection and reconsideration.

What about revision that’s aimed at changing modern-day perceptions? That question is central in Howard LaFranchi’s story today from Buenos Aires, Argentina, where debate around a detention center turned museum stirs something deep.

Argentina was practically defined by brutal state-led terror from the mid-1970s to early 1980s. Think dissidents being thrown from airplanes. The country also modeled the healing work of delivering accountability. Is Argentina’s narrative now being given added nuance, or is it facing an assault on truth?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

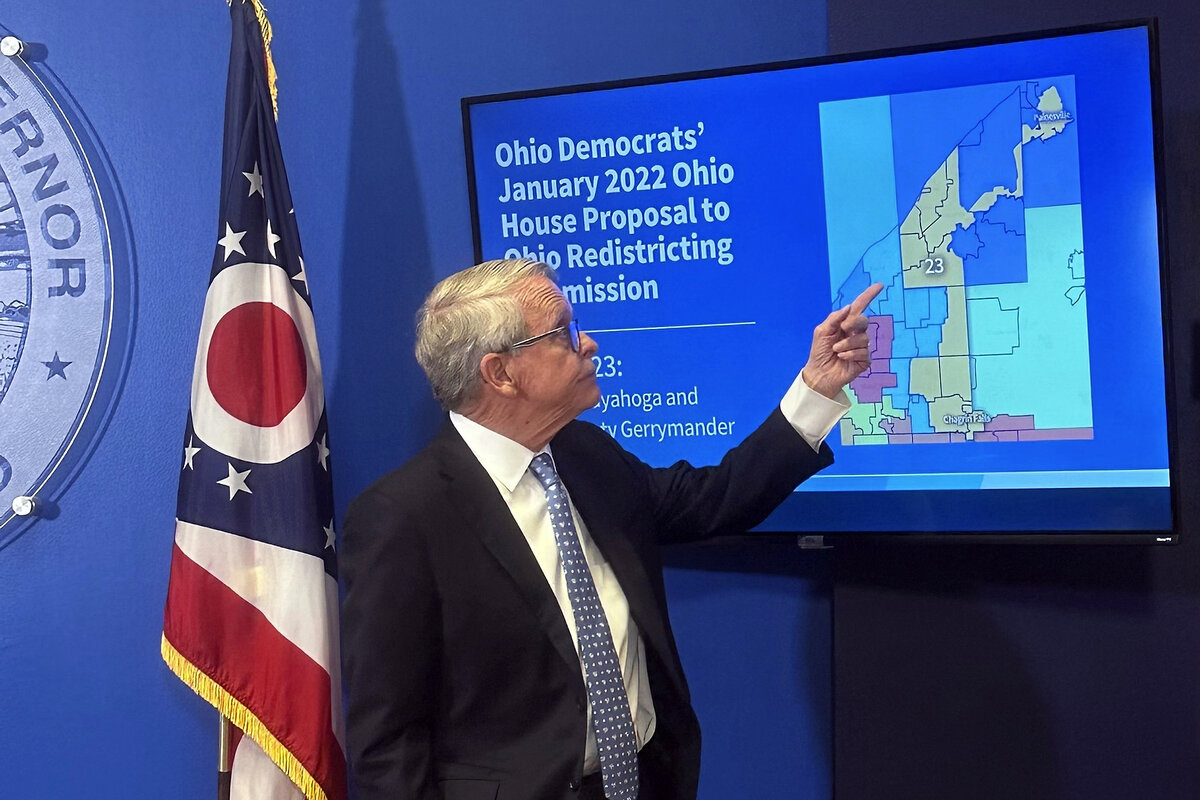

On Ohio ballot, a retired justice’s crusade to make politics competitive again

One reason compromise has become so hard in politics is that many districts are no longer competitive – and therefore, candidates don’t have to win voters beyond their partisan base. Reforming how districts are drawn is an attempt to fix that.

Since retiring as chief justice of Ohio’s Supreme Court, Maureen O’Connor has become a prominent champion for reforming the process of how political districts are drawn in Ohio.

That has pitted Ms. O’Connor, a Republican who previously served as lieutenant governor, against erstwhile GOP allies.

Republicans have fine-tuned the drawing of boundaries to maximize the number of districts where Democrats have virtually no chance of winning. That has enabled them to deliver veto-proof majorities in the legislature.

So Ms. O’Connor has shaped a ballot proposal to instead empower an independent citizens commission to determine political boundaries.

Only a handful of other states have such a commission. Should the proposal pass, Ohio could become a test case for how a red state weighs the political voice of majority and minority factions. Proponents say a fairer redistricting process led by citizens would boost civic engagement and elevate lawmakers who work across the aisle.

But opponents argue that a citizens commission, whose members would be appointed by retired judges, wouldn’t be politically accountable.

“If the voters don’t like the way they draw the maps, they can vote them out of office,” says Jane Timken, a former state GOP chair.

On Ohio ballot, a retired justice’s crusade to make politics competitive again

When Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor was asked about her retirement plans after 12 years presiding over Ohio’s Supreme Court, she invoked an Italian phrase: dolce far niente – the sweetness of doing nothing.

Instead, a week later she began working on a long-shot ballot proposal that would upend how the state’s political seats are decided. That was January 2023. Now comes the moment of truth.

Republicans who dominate state government have fine-tuned the drawing of boundaries to maximize the number of districts where Democrats have virtually no chance of winning. That has enabled them to deliver veto-proof majorities in the legislature, despite averaging only 54% of votes cast.

Ms. O’Connor, a Republican who served as lieutenant governor before being elected to the state’s highest court in 2002, has become a prominent champion for reforming that boundary-drawing process in Ohio. That has pitted her against erstwhile GOP allies.

In November, voters will be asked if they want to loosen politicians’ control over redistricting. The ballot proposal that Ms. O’Connor shaped would empower an independent citizens commission to determine political boundaries.

Only a handful of other states have such a commission. Should the proposal pass, Ohio could become a test case for how a red state weighs the political voice of majority and minority factions. Proponents say a fairer redistricting process led by citizens would boost civic engagement and elevate lawmakers who work across the aisle. However, experts warn that creating more representative districts can be challenging.

The stakes are high for politicians across Ohio’s increasingly polarized political spectrum and for reformers in other states trying to defuse their own redistricting battles.

Her solution for a ‘broken’ system

As chief justice, Ms. O’Connor sided repeatedly with three Democrat justices in 2022 to strike down maps submitted by the state’s GOP-led redistricting commission. The court ruled that the maps for state and federal districts were unconstitutional and ordered the commission to draw representative districts. Three other Republican justices dissented.

The impasse was ended by a federal court ruling that Ohio had to adopt one of the rejected maps for the 2022 cycle.

“The system is broken,” Ms. O’Connor says. “Seven unconstitutional maps prove that.”

Her solution is to put 15 citizens, divided equally among Republicans, Democrats, and independents, in charge, working toward a common goal of producing maps that better reflect voters’ political preferences. Had the politicians on Ohio’s current redistricting commission worked in good faith last time, they might have achieved this goal, she says.

“It all boils down to motivation,” she says.

Undaunted by slings and arrows

Ohio has been here before: In 2015 and 2018, voters overwhelmingly approved constitutional amendments to overhaul its redistricting process and prohibit gerrymandering. But the bipartisan commission that was supposed to reflect public opinion became a battering ram for Republicans seeking to cement a supermajority in the legislature.

Ms. O’Connor says she was always skeptical of the political makeup of the commission, which she calls a “Trojan horse” in the overhaul. In 2021, the two Democrats on the seven-person commission objected to the maps, triggering a review by the state supreme court. That’s when she cast the swing vote with Democratic justices to find the maps unconstitutional.

Her ruling infuriated Republicans; some lawmakers called for her impeachment. The rancor only grew as the court reviewed and rejected multiple GOP-authored maps as partisan gerrymanders. By then, Ms. O’Connor had become convinced that Ohio would be better served by a citizens commission, a view she aired in a concurring opinion from the bench.

Having turned 70, she faced mandatory retirement. When her official portrait was unveiled at the courthouse, two Republican justices didn’t attend, citing scheduling conflicts. She also learned that the state GOP had removed her portrait from its wall. Such snubs don’t trouble her, she insists, since her party affiliation was never tribal, especially when she ruled from the bench.

“People think that I suffered the slings and arrows of all this nastiness and that must have affected me,” she says. “It didn’t.”

Analysts say Ms. O’Connor is a throwback to the moderate type of Midwest Republican who has been largely expunged from a Trump-infused party.

Still, “it’s unusual for a former elected official to be out front on a reform that the Republican Party is generally opposed to,” says Jonathan Entin, a professor emeritus of law at Case Western Reserve University.

He chalks this up to her frustration with the refusal of politicians to heed the court’s redistricting ruling. “I think she’s just been really offended at the way this process played out,” he says.

Most retired justices join big law firms and are amply remunerated. Ms. O’Connor chose a different path as an unpaid campaigner for constitutional reform.

“She’s deeply committed to the public good, the way that she sees it,” says Steven Steinglass, former dean of Cleveland State law school and a friend of Ms. O’Connor, an alum.

Uphill battle for ballot initiative

Ms. O’Connor won’t be voting for the Republican presidential nominee this year. “I’ve never voted for Donald Trump,” she says.

But his name on the ballot will juice turnout and make it harder to pass a constitutional amendment that Republicans in Ohio oppose, says Paul Sracic, a political scientist at Youngstown State University.

It’s also a complex issue, not made easier by the GOP-authored ballot language, which critics called deceptive, but which Ohio’s supreme court let mostly stand.

“The default position of voters is no. If they don’t understand something, they vote no,” he says.

A Founding Father’s role

Gerrymandering is as old as representative democracy. It takes its name from a portmanteau of Founding Father Elbridge Gerry and the salamander-shaped district he created as governor of Massachusetts to break up a stronghold of his Federalist Party rivals.

The map-drawing process, usually based on the census, determines – among other things – how seats are apportioned in the House of Representatives and or state legislatures. When either body is closely divided, strategic mapmakers can flip control to the other party.

“Either party will do anything to gain an advantage,” says Benjamin Schneer, an assistant professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School.

In 2021, Ohio lost a congressional seat, which required a GOP-led redrawing of federal districts, along with new maps for the state legislature to adjust for population change. The ensuing legal battle over both sets of maps cast a national spotlight on Ohio’s hardball politics.

‘This is about power’

But in states such as Colorado, Arizona, and Michigan, where independent bodies draw district lines, the process was less fraught and produced fairer maps that led to competitive races in which candidates usually had to appeal to voters outside their partisan base.

Much depends “on the design of the commissions,” says Professor Schneer, who consulted on Arizona’s commission. But “their maps tend to be less gerrymandered.” It can also dramatically change the makeup of the state legislature.

In Michigan, where voters approved the creation of a citizens commission in 2018, Democrats now hold a statehouse trifecta for the first time in decades. Derrick Clay, a Democratic lobbyist in Columbus, Ohio, says that’s why GOP leaders oppose his state’s ballot measure.

“This is about power, and they don’t want to give up their power,” he says. “The only people who lose out in this scenario are the citizens.”

But opponents argue that a citizens commission, whose members would be appointed by retired judges, wouldn’t be politically accountable.

“If the voters don’t like the way they draw the maps, they can vote them out of office. There is accountability,” says Jane Timken, a former state GOP chair.

Proponents note that such accountability depends, however, on seats being competitive, which isn’t the case in much of Ohio.

The point of an independent redistricting process isn’t to favor one party or another, but to make elections more competitive – and thus more representative.

“All power comes from the citizenry,” says Ms. O’Connor. “And we delegated it to our representative system …That means that they have to reflect what the citizens want.”

Today’s news briefs

• Action on Korean Peninsula: North Korea says it will completely cut off roads and railways connected to South Korea beginning Oct. 9 and fortify border areas, state media reported, heralding a further escalation in activity close to the demarcation line.

• Election Day attack thwarted: The FBI arrests an Afghan man who officials say was inspired by the Islamic State militant organization and was plotting an Election Day attack targeting large crowds in the United States.

• Mozambique votes: The presidential election could extend the ruling party’s 49 years in power since the southern African nation gained independence from Portugal in 1975. Some candidates allege manipulation of the election process.

• Nobel Prize in chemistry: David Baker, Demis Hassabis, and John Jumper are recognized for their work with proteins. Two of them created an artificial intelligence model that has been able to predict the structure of virtually all the 200 million proteins identified by researchers.

Reframing a dictatorship: Argentine human rights museum under fire

Now to our story on who gets to write history. In Argentina, decades of well-documented crimes and court hearings are being questioned by the nation’s new populist, libertarian leadership.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Alfredo Sosa Staff photographer

A former Argentine navy mechanics school that served as a dictatorship-era torture site was transformed into a museum, and last year recognized by the United Nations as a site of world heritage and historic importance. But the story that the ESMA Museum and Memory Site is trying to document – including a period of state terror used against citizens – is now being questioned by Argentina’s most powerful politicians.

President Javier Milei and his vice president, Victoria Villarruel, who came to office last year, are outspoken about what they see as a one-sided narrative about Argentina’s military dictatorship. They have taken steps to halt investigations into dictatorship-era crimes, while Ms. Villarruel has organized visits to imprisoned officers convicted of crimes against humanity.

The skepticism around Argentina’s documented history has opened the gates to fresh and bitter questioning of how the dictatorship – and torture sites like ESMA – should be remembered.

Ana María Soffiantini, a torture survivor detained at ESMA in 1977, compares her experience there with what she calls the government’s “very different perspective. History is always written by the winners. And they have won,” she says of Mr. Milei’s radical libertarian approach, “so they want their history.”

Reframing a dictatorship: Argentine human rights museum under fire

Ana María Soffiantini, a retired school principal and grandmother of 13, indicates with a sweep of her hand the cramped, dark space where she was held captive nearly five decades ago.

In 1977, when both she and her husband were part of a leftist revolutionary organization, they were kidnapped by Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship for “subverting” the government. She was detained at the notorious Navy School of Mechanics (ESMA) for a year, with a hood over her head and chains on her ankles.

“While lying here we listened to every sound, we kept track of every movement to try to figure out where we were and what was going on around us,” Ms. Soffiantini recalls.

She was one of more than 5,000 labor organizers, leftist Catholics, and student activists grabbed from their homes and the streets and held at ESMA between 1976 and 1983. Only a few hundred came out alive.

Argentina has made a name for itself in a region that was wracked by bloody coups and military dictatorships; it’s a reputation based not only on some of the junta’s brazen crimes, like kidnapping prisoners’ babies and offering them for adoption to military families, but also because of subsequent governments’ work to hold people accountable for state-led terror. Argentina has tried more than 300 cases of dictatorship-related crimes against humanity since 2006, with many still in adjudication.

Today, the once notorious detention and torture center where Ms. Soffiantini was held is a museum and memorial, open to the public since 2015. Last year it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, one of the few venues from recent history to figure on the organization’s list. But within weeks of ESMA’s designation as a space of global historic importance came the election of right-wing populist President Javier Milei.

Mr. Milei and especially his vice president, Victoria Villarruel, are outspoken about what they see as a one-sided narrative about the military dictatorship, bolstered by institutions like the ESMA Museum and Memory Site. Both of them have taken steps to halt investigations into dictatorship-era crimes, and Ms. Villarruel, daughter of a prominent military family, questions the commonly accepted estimate that 30,000 people were killed during the dictatorship. She has also organized visits to imprisoned officers convicted of crimes against humanity.

The president and his allies’ skepticism about Argentina’s documented history has opened the gates to fresh and bitter questioning of how the dictatorship – and torture sites like ESMA – should be remembered.

Argentina is facing “intense debate over what has been a widely accepted depiction of a painful historical period,” says Ernesto Verdeja, an associate professor of peace studies at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. He says that is reopening “what seemed settled questions about who was right and who was wrong ... and how society should view its past” and try to build its future.

“Sites like ESMA represent much more than what happened inside them,” Dr. Verdeja says.

New elections, new history?

Between 1976 and 1983 Argentina’s military dictatorship carried out a violent, repressive campaign against suspected left-wing political opponents. It took place in the global context of the Cold War, when powerful countries such as the United States heightened fears of communist takeovers, particularly in Latin America.

It was from ESMA, part of a sprawling military complex on a leafy boulevard in one of Buenos Aires’ tonier neighborhoods, that the military dictatorship carried out its notorious “death flights.” Detainees were taken up in small planes and pushed to their deaths from the open rear hatch into the sea below. The flights gave the world the transitive verb “to disappear” someone.

The emergence of a different historical narrative, seeking to highlight the dangers posed by leftist groups, is closely linked to the rise of new political powers, says Dr. Verdeja.

“The rejection of what has long been accepted truth is very much driven by domestic politics, by a sense of national crisis,” he says.

Vice President Villarruel has long argued that the military was fighting a legitimate civil war to save Argentina from Marxist rule. Since her election alongside Mr. Milei she has championed efforts to rehabilitate the armed forces’ reputation.

Her robust defense of the dictatorship strikes many Argentines as exaggerated. But, a growing number of conservatives say that after four decades of a single, one-sided presentation of what happened under military rule, it is indeed time for a closer look.

“Unbelievable”

Back at the ESMA museum, Director Mayki Gorosito is adamant that its purpose is not to interpret events, but to chronicle the crimes committed by a state against its own people.

“We present the facts of what took place here based on the record of the testimonies given in the many cases and the judgments of courts of law,” she says. “It would be dangerous for democracy ... to lose that focus on the crimes committed during state-practiced terrorism.”

As she speaks, high school groups and other visitors walk around the floors above, where detainees were held, and where some were forced to produce dictatorship propaganda. Monitors play excerpts from the court testimony of both ESMA workers and their victims.

In the basement, three high school boys stand in the doorway through which detainees were taken to the planes from which they would be pushed to their death.

“Unbelievable,” one boy whispers to his friend.

Even if Ms. Gorosito’s mission is simply to demonstrate that what happened at ESMA is fact, proven in court, she must be cautious, she says. Not only is she managing a tinderbox of historical memories, but her museum is threatened by the same austerity cuts that the new government has imposed on all government agencies.

Mr. Milei rode into office on a wave of discontent over Argentina’s hyperinflation, stagnant economy, and rising poverty. He has proceeded with drastic steps such as eliminating many ministries and slashing the budgets of those remaining.

The ESMA “site itself is not threatened,” says Horacio Pietragalla, a former secretary of human rights. “What is threatened by budget cuts is all the research that continues into the crimes of the era.”

Mr. Pietragalla is a dictatorship-era kidnapping victim himself, placed with a military-related family after his birth parents were killed in clashes with police. He says he is afraid that the government is trying to “erase” history by gutting the institutions that have established the facts of a dark past.

Ms. Gorosito, the museum director, actually quit her job when Mr. Milei took office last December. She was persuaded to return, but only on condition that none of the existing staff be fired, that support for ESMA survivors continue, and, perhaps most critically, that none of the exhibits in the museum be modified or removed.

Ms. Soffiantini, the torture survivor detained at ESMA, has a simple explanation for the difference between her experience and the government’s “very different perspective. History is always written by the winners. And they have won,” she says of Mr. Milei’s party. “So they want their history.”

The Philippines has held out on legalizing divorce. Is it set to call it quits?

While activists around the world fight for marriage equality, the Philippines is considering “separation equality” – whether, and under what conditions, married couples should be allowed to divorce. The debate delves into issues of religious freedom, women’s safety, and family welfare.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The Philippines is one of the last countries in the world where the majority of citizens cannot legally divorce. But with a divorce bill currently awaiting consideration in the Senate plenary, that could soon change.

Senators shot down a similar bill in 2018, and although polls show Filipinos’ support for divorce under certain circumstances is growing, opposition from conservative religious groups remains a major obstacle. Many in this camp want to preserve the traditional Christian view of marriage as a sacred and indissoluble institution. They worry that any rush toward legalizing civil divorce could undermine Filipino families – the foundational aspect of society, according to the country’s constitution.

The bill’s advocates, meanwhile, say divorce offers women a way to sever ties with abusive partners, and to rebuild their lives with safety and dignity.

“If there’s a concept of marriage equality ... there’s also a concept called, for lack of a better term, ‘separation inequality,’” says Jayeel Cornelio, sociologist of religion. In the Philippines, “You can be annulled; you can have a legal separation. But we know there are legal restrictions,” and in cases of domestic abuse, these restrictions primarily protect the perpetrator of violence.

The Philippines has held out on legalizing divorce. Is it set to call it quits?

In the predominantly Catholic Philippines, where Christian values are deeply intertwined with national identity, an ongoing debate over legalizing divorce pits traditional views of marriage against emerging calls for individual freedoms and women’s safety.

Generally speaking, Filipino couples wishing to separate have two options: File for legal separation, which permits spouses to live apart without legally terminating their marriage, or pursue an annulment. The latter process is often costly and demands proof that the marriage was invalid. Other than Vatican City, the Philippines is the only country in the world where the majority of citizens cannot legally divorce.

That could soon change. A divorce bill, narrowly approved by Congress in May, is currently awaiting consideration in the Senate plenary.

The Senate shot down a similar bill in 2018, and although polls show Filipinos’ growing support for divorce under certain circumstances, opposition from conservative religious groups remains a major obstacle. Many in this camp are proud that the Philippines is one of the last countries without civil divorce, and want to preserve traditional Christian views of marriage as a sacred and indissoluble institution. The bill’s advocates, meanwhile, have largely focused on how divorce offers women a means to sever ties with abusive partners, and rebuild their lives with safety and dignity.

Framing divorce as a human rights issue highlights the shortcomings of the Philippines’ current family law, says Jayeel Cornelio, sociologist of religion and the associate dean for research and creative work at the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University.

“If there’s a concept of marriage equality, ... there’s also a concept called, for lack of a better term, ‘separation inequality,’” he says. “You can be annulled; you can have a legal separation. But we know there are legal restrictions,” and in cases of domestic abuse, these restrictions primarily protect the perpetrator of violence.

“It leaves victims without the ability to remarry,” he says.

Easy way out?

The bill – called the Absolute Divorce Act – outlines limited grounds for divorce, including irreconcilable differences. It also incorporates existing justifications for annulment and legal separation, such as abandonment and infidelity. The act would not legalize no-fault divorce, and except in cases in which the safety of a spouse or child is under threat, it requires a 60-day cool-off period postpetition, giving couples a final chance to reconcile.

If this law had existed in 1995, when Ruby Ramores confronted her husband about an affair he was having, she believes it may have spelled the end of their 13-year marriage.

“It could have been an easy way out,” she says. “I reached the peak, and I really wanted to separate from him.”

Instead, when the couple saw the toll their possible separation was taking on their six children, they chose to salvage their marriage.

With the help of a priest, the couple worked to rebuild trust. Today, they are active lay leaders, and in June, they spearheaded the creation of the Super Coalition Against Divorce, a nationwide network of organizations lobbying lawmakers to oppose the proposed divorce law.

“What we are protecting here is the institution of marriage,” says Mrs. Ramores, “the value of family in the society as the basic unit, [and] the welfare of the children and future generations.”

It’s a message echoed by religious leaders and politicians alike. Earlier this year, Sen. Joel Villanueva, son of an influential evangelist, raised concerns about Filipinos rushing to get “drive-thru” divorces over trivial arguments. The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines issued a statement urging cautious reflection before “we jump into the divorce bandwagon.”

“Think about the many times your parents had gotten into each other’s nerves and were almost tempted to call it quits,” wrote Bishop Pablo Virgilio David of Kalookan, president of the conference. “Think of the sufferings that you would have had to endure if civil divorce had already been available as a remedy for what your own parents may have thought back then were ‘irreconcilable differences’ between them,” he added.

The prelate suggested that any rush toward legalizing civil divorce could undermine Filipino families – the foundational aspect of society, according to the country’s constitution. Mr. David also acknowledged that not all married couples have been “joined together by God,” and thus could have their unions annulled. However, he stressed that such measures should be approached with deliberation and compassion, especially considering the potential impact on children.

What makes families strong

Compassion was elusive in Cici Leuenberger Jueco’s 30 years of married life.

“I experienced all types of abuses – physical, emotional, economic, sexual – I encountered all of them from him,” she says about her late husband, who died by suicide in 2017. “I could have had a nervous breakdown, but the Lord didn’t permit it because my children would suffer.”

Ms. Jueco eventually became numb to the daily battering. Then, in 2002, her husband beat and raped her so violently she ended up in the hospital, where doctors told her she came perilously close to dying.

“I had tried my best to work things out,” she says. “I endured hardships and suffering, but everything has its limits. I couldn’t just wait for him to kill me.”

It took another three years for Ms. Jueco to build up the courage to file criminal charges against her husband, who was later deported to his home country of Pakistan. In 2012, she organized Divorce for the Philippines Now International, an organization that advocates for legalizing divorce and provides a platform for separated couples to voice their concerns about the Philippines’ current marriage laws.

“We cannot strengthen the family or the country’s institution of marriage if we fail to protect those who suffer from abusive relationships,” she says.

Mr. Cornelio, the sociologist, agrees.

“Divorce itself is not inherently damaging,” he says. “There are ways to implement divorce without compromising ... marriage as a social institution, by ensuring it is only available for specific issues” such as infidelity and domestic violence. In these cases, divorce would actually protect the family, he argues.

The freedom to believe – or not

But there’s another, more fundamental issue bothering him.

Although nearly 88% of the Philippines’ population is Christian, “It’s not a Christian country,” he says. “Freedom of religion and belief is allowed ... and that includes the freedom not to believe.”

In some ways, this question about the separation of church and state is more important than the debate over divorce’s impact on society, Mr. Cornelio argues. “If a Filipino chooses not to believe in the doctrine of the Catholic Church when it comes to the sanctity of the family, and they have a valid reason for arguing that, then shouldn’t the state protect that conviction as well?”

Filipinos’ attitudes toward divorce are complex. According to a Social Weather Stations survey released in July, 50% of adults support the legalization of divorce for “irreconcilably separated couples,” while 31% oppose it. A more recent survey conducted in collaboration with church-based media organizations suggests the public is still broadly resistant to divorce, with only 34% supporting divorce due to “irreconcilable differences.” But when divorce was framed in the context of abuse, that figure rose to 51%.

Some clergy, including Bishop Gerardo Alminaza of San Carlos in the central Philippines, want to turn the focus inward. If the church’s teachings about family and marriage are solid, he says, “We have nothing to worry about, even if there is an existing divorce law in the country.”

“With or without divorce, dysfunctional families and conflicts will continue to challenge the institution of marriage,” says the prelate. “However, because the formation within our community is weak, we tend to view someone’s remedy as someone else’s poison.”

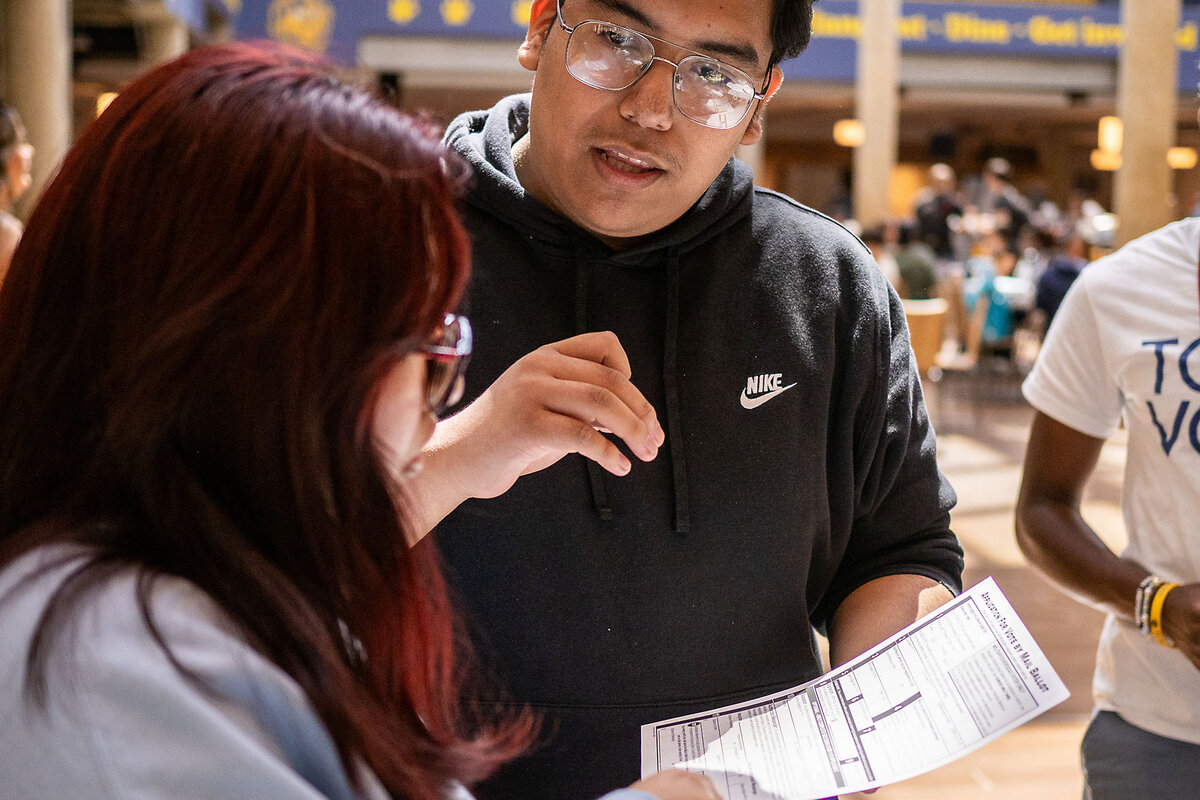

College students voted in big numbers in 2020. A look at what 2024 might hold.

What effect will young voters have on the November election? Trends from prior years show that their habits are changing over time, often motivated by issues that matter to them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Jon Marcus The Hechinger Report

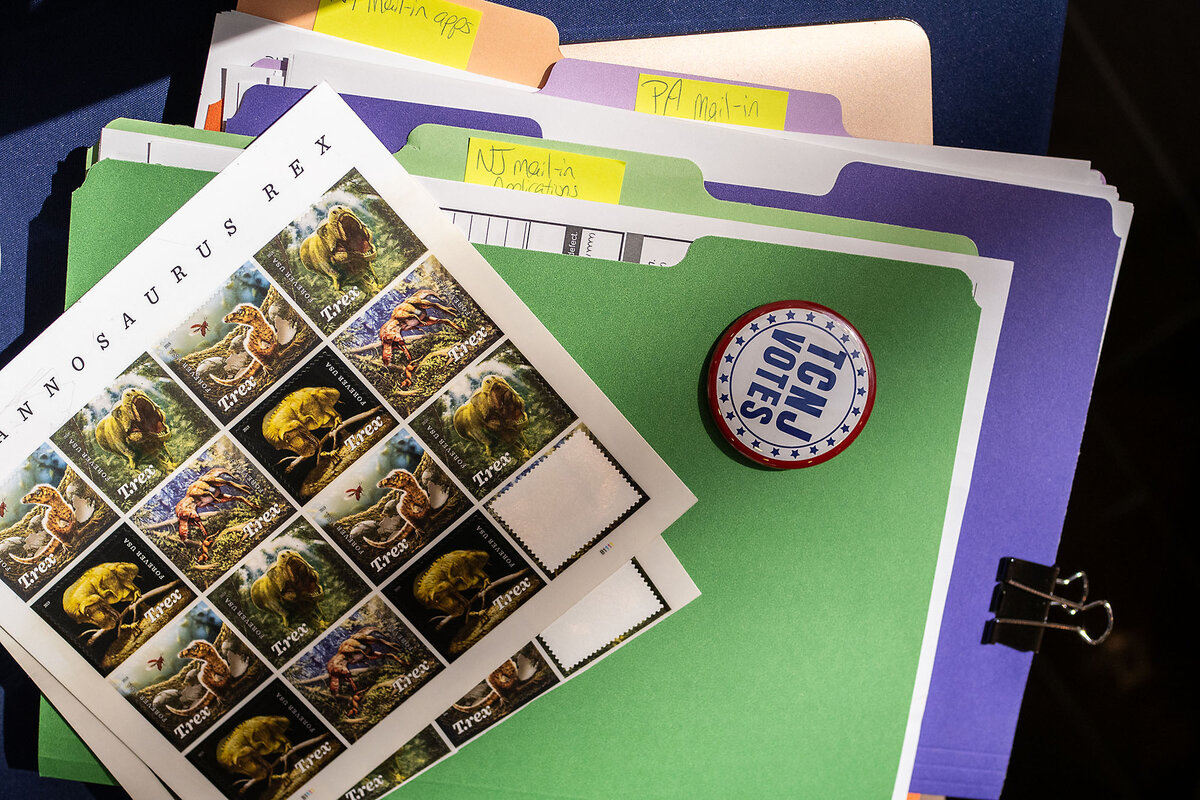

At The College of New Jersey in Ewing, first-year student Roman Carlise waits in line at a voter registration table.

He’s not a fan of the political skirmishing this election season. It bothers him watching people bickering, “when they’re supposed to fix the problems.”

Americans ages 18 to 24 have historically voted in very low proportions – 15 to 20 percentage points below the rest of the population.

But rates of voting by young people have quietly been rising to unprecedented levels, despite attempts in some states to make it harder for them.

More than half of Americans ages 18 to 24 turned out for the 2020 general election, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That proportion was up by more than 8 percentage points from 2016, and has been closing in on the voting rate for adults of all ages. Among college students, the proportion who voted was even higher.

Young people are propelled by concerns that directly affect them, such as global warming, the economy, reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights, student loan debt, and gun safety.

Mr. Carlise plans to be among those casting a ballot this year. “I’m just not the type to say, ‘There’s nothing I can do.’”

College students voted in big numbers in 2020. A look at what 2024 might hold.

Bethany Blonder and her friends line up at the voter information table in the student union before organizers have even finished setting it up in time for lunch.

It’s true that a fire drill has chased them there from their dorm on the campus of The College of New Jersey, or TCNJ. But the women are also quick to rattle off what they see as the existential issues that make them hell-bent on casting their ballots in the general election.

Climate change, for instance.

“All of our lives are at risk – our futures – and the lives of our neighbors, the lives of our friends,” says Ms. Blonder, a freshman from Ocean Township, New Jersey. “Every time there’s a hot day outside, I’m like, ‘Is this what it will be like for the rest of my life?’”

Americans ages 18 to 24 have historically voted in very low proportions – 15 to 20 percentage points below the rest of the population as recently as the presidential election years of 2008 and 2012, with an even bigger gap in the 2010 midterms, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But rates of voting by young people have quietly been rising to unprecedented levels, despite their lifetimes of watching government gridlock and attempts in some states to make it harder for them to vote.

More than half of Americans ages 18 to 24 turned out for the 2020 general election, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That proportion was up by more than 8 percentage points from 2016, and has been closing in on the voting rate for adults of all ages. Among college students, the proportion who voted was even higher.

Young people say that they’re propelled by concerns that directly affect them, such as global warming, the economy, reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights, student loan debt, and gun safety.

As early as elementary school, “we grew up having to learn about lockdowns” in response to mass shootings, says Andrew LoMonte, one of the students staffing the voter table. “What people are realizing is that the issues the candidates are talking about actually matter to us.”

The political division they’ve witnessed hasn’t discouraged young voters, says Mr. LoMonte, a sophomore political science major from Bloomfield, New Jersey, who is wearing a “TCNJ Votes” T-shirt. It’s made them more determined to become involved.

“You’d think the dysfunction would scare people off, but it’s a motivator,” he says.

More young people are voting and having a “decisive impact”

Sixty-six percent of college students voted in 2020, up 14 percentage points from 2016, according to the National Study of Learning, Voting and Engagement at Tufts University’s Institute for Democracy and Higher Education.

Younger students ages 18 to 21 voted at the highest rates of all, portending a continued upward trend, the study found.

“You’re seeing a generation of activists. I mean, very young – 16, 17,” says Jennifer McAndrew, senior director of communications and planning at Tufts’ Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life. “It goes back to them engaging each other and saying, ‘This isn’t a perfect system. But the only way we can change it is by voting.’ ”

This is already showing some results.

Young voters had “a decisive impact” on Senate races in 2022 in battleground states including Wisconsin, Nevada, Georgia, and Pennsylvania, according to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, or CIRCLE, which is also based at Tufts.

Youth voter registrations have particularly soared in states considering referenda relating to abortion restrictions. And college students were widely credited last year with helping elect a liberal candidate to the Wisconsin state Supreme Court, which is due to take up two major abortion cases.

After seeing results like those, “young people have become more aware of their own political power within states and districts,” Ms. McAndrew says.

They have also registered and voted at high rates in several swing states. Michigan had the biggest turnout in the country of voters 30 and under in 2022 – 36% – according to CIRCLE. Young people in Pennsylvania have turned out at above-average rates in the last three presidential races.

The nonpartisan voter registration group Vote.org reports that it has registered a record 800,000 voters under 35 in time for the November general election. Of the more than 1 million new voters it signed up in all, Vote.org says 34% were 18, compared to 8% during its 2020 voter registration drive.

The Big Ten Conference runs a voter turnout competition that has increased student voter turnout at member schools. The organization People Power for Florida held its fourth annual “Dorm Storm” for students at eight universities in August and registered 728 new voters during move-in week, the most ever, the group said.

Both presidential campaigns are using social media and targeting students on college campuses in pivotal states. The Democratic National Committee has hired banner-towing airplanes to fly over college football games on behalf of Democrat Kamala Harris, while Republican Donald Trump has a TikTok account and has courted social media influencers.

And Taylor Swift’s recent endorsement of Vice President Harris and call to her fans to register and vote helped drive over 24 hours a more than 20-fold increase in visitors to the federal government website Vote.gov, which provides voter registration information. “If you are 18, please register to vote,” Ms. Swift later said at the MTV Video Music Awards. “It’s an important election.”

Ms. McAndrew gives particular credit for the rising numbers of young voters to the gun-safety organization March for Our Lives, founded by survivors of the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida, that killed 17.

“They have led protests, of course,” she says. “But they have also said, ‘Here’s how you call your state rep. Here’s how you call your state senator. Here’s how you register to vote.’”

Hurdles to voting: ID confusion, state restrictions

None of these things mean that high youth voter turnout in November is assured. The proportion of college students who voted in the 2022 midterms was down from the record set in 2018. An analysis by CIRCLE shows that, for all of the enthusiasm and organizing, voter registration among Americans under 30 in most states so far is behind where it was around this time in 2020.

Meanwhile, several states have imposed restrictions that affect student voting – limiting polling locations, voting hours, absentee voting, ballot boxes, and the use of student IDs to vote. A survey in 2016 found that one in five students who were registered to vote but didn’t cast ballots said it was because they had issues with or didn’t think they could use their IDs. (State student ID laws for voting are listed in The Hechinger Report’s “College Welcome Guide.”)

“Even when young people would have been able to vote, they sometimes tell us they didn’t even try because they thought they needed another kind of ID,” says Ms. McAndrew, at Tufts.

A new law in Florida imposes strict limits on third-party organizations, including student groups, that try to sign up new voters. The law imposes fines of up to $250,000 if these groups fail to follow a list of rules that include registering with the state’s elections division.

Although a little-known federal rule requires colleges and universities that accept federal money to encourage voting, universities in some states are newly fearful of antagonizing legislatures that have targeted campuses over anything that could be considered political.

“We have seen some places where they’re a bit more cautious and changed their approach a little bit to make sure they’re doing everything by the book,” says Clarissa Unger, co-founder and executive director of the Students Learn Students Vote Coalition, which includes about 350 nonpartisan voting advocacy groups. “There are certain states where it’s become much harder, and those are states a lot of our organizations are focused on even more.”

Not all groups of students vote in equally high numbers. Seventy-five percent of students at private, nonprofit colleges voted in 2020, for instance, compared to 57% at community colleges. Students majoring in education, social sciences, history and agricultural and natural resources turned out at the highest rates; those in engineering and technical fields, at the lowest.

“Engineering is really difficult and there’s a lot of heavy coursework,” says Liora Petter-Lipstein, a senior public policy major at the University of Maryland, who set out to learn why engineering students there voted at lower levels than their classmates. “They don’t really have time for other things and voting doesn’t become a priority.”

Many young Americans also still don’t see the point, Ms. Petter-Lipstein says. “A lot of people said they didn’t think their vote matters. They don’t feel informed enough to vote, they missed the ballot request deadline or they say, ‘Oh, I’m just not a political person.’ I was talking to a friend of mine who happens to be an engineer who didn’t even realize that they could vote in Maryland.”

To them, she tries to connect the election with issues of interest. “A lot of what we’ve been focusing on has been, ‘Hey, did you know that these things are on the ballot?’” That includes, in Maryland, a referendum to add the right to an abortion to the state constitution’s declaration of rights.

At TCNJ, more than 83% of students voted in 2020, putting the college in the top 20 among higher education institutions nationwide, according to the nonprofit Civic Nation, which advocates for people to vote.

First-year students here are required to take a community service course, there’s a voter registration contest among residence halls, and students get text reminders about voting deadlines. TCNJ, just outside the capital of Trenton, is also part of a voting competition with other New Jersey campuses, called the Ballot Bowl.

Even before they arrive, however, students are politically active, says Brittany Aydelotte, director of the school’s Community Engaged Learning Institute.

“They’re really coming in with much more knowledge about social justice issues,” Ms. Aydelotte says. “Social media has a huge impact. They’ve been able to figure out how [politics] relates to them personally. Our goal is that they leave here thinking, ‘Hmmm, what else can I do?’ ”

The Hechinger Report, U.S. Census Bureau

The polarized politics of the times makes students even more eager to create change, says Jared Williams, the president of TCNJ’s student government.

“It’s not enough to throw our hands in the air and give up,” says Mr. Williams, a senior political science major from Union, New Jersey. “It’s very easy to get disillusioned. But there’s no way to end that cycle if you don’t vote.”

Besides, adds his vice president for governmental affairs, Aria Chalileh, who is also a senior majoring in political science: Students “are realizing that these issues are being talked about. They aren’t issues that might affect them 50 years down the line. They affect them right now.”

That’s what brought freshman Roman Carlise to the line at the voter registration table, he says.

The political skirmishing of this election season “gets on my nerves,” says Mr. Carlise. “That bothers me – seeing people bicker when they’re supposed to fix the problems.”

But he plans to vote anyway, he says.

“I’m just not the type to say, ‘There’s nothing I can do.’”

This story about college student voting rates was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Live, from New York, it’s the ‘SNL’ origin story ‘Saturday Night’

“Saturday Night Live,” which is celebrating its 50th season, launched the careers of scores of comedians. A diverting new film about the TV show’s premiere features frenetic creativity – and its toll.

Live, from New York, it’s the ‘SNL’ origin story ‘Saturday Night’

The entertainingly madcap “Saturday Night” takes place in the frenetic 90-minute run-up to the airing of the first “Saturday Night Live” show on Oct. 11, 1975. The events appear to be happening almost in real time, and in one continuous shot. The film’s director, Jason Reitman, maintains this deception by whizzing his camera in and out of dressing rooms, hallways, soundstages, the streets outside New York City’s 30 Rockefeller Plaza – just about everywhere.

All this vertiginousness isn’t exhausting because Reitman and his actors are always giving us something to look at and listen to. The freneticism isn’t a stylistic affectation. It’s central to the story. “Saturday Night” is about how creativity can sometimes issue from mayhem. It’s also about how sometimes mayhem is just mayhem.

In a few quick brushstrokes, we are introduced to the cast and crew. Lorne Michaels (Gabriel LaBelle), the creator and driving force of “SNL,” is a human tornado trying to wrangle a million movable parts and swelled heads. The nervous NBC honchos, notably Dave Tebet (Willem Dafoe), are ready to pull the plug right up until airtime and instead substitute a rerun of Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show.” At least, Tebet figures, the rerun will draw a bigger audience.

When I first heard this film was in production, I assumed it wouldn’t work because audiences – or at least those old enough to remember – wouldn’t buy a cast of young actors impersonating the likes of John Belushi, Chevy Chase, and Gilda Radner. (They are played by, respectively, Matt Wood, Cory Michael Smith, and Ella Hunt.) But the performers for the most part deport themselves well. Along with Kim Matula (as Jane Curtin), Emily Fairn (Laraine Newman), and Lamorne Morris (Garrett Morris, no relation), they suggest the Not Ready for Prime Time Players without attempting to strictly mimic them.

Unfortunately, several of these players, notably Curtin, Newman, and, more surprisingly, Belushi and Radner, are given rather short shrift. The bulk of the film’s focus is on Michaels; his wife Rosie Shuster (Rachel Sennott), one of the show’s writers; and Chase, who comes across as the protagonist with the fattest ego – quite an achievement in this crowd. A backstage confrontation between Chase and a visiting Milton Berle (a great J.K. Simmons) encapsulates the movie’s central conflict of Old School vs. Young Turks. Berle is haughtily dismissive of these upstarts and predicts they will be forgotten. Chase represents the generation that grew up on television long after Uncle Miltie left the airwaves. What Berle and the NBC executives didn’t realize that fateful night is that “SNL” created a new audience along with a new show.

Like most actual “SNL” episodes, “Saturday Night” is a hit-and-miss affair, but somehow this seems appropriate to the subject. Some of the scenes, like the ones featuring the Muppets, are rather dim. Others, notably confrontations involving the viperish writer Michael O’Donoghue (Tommy Dewey), are spot on. The show’s uptight script supervisor – i.e., NBC censor – doesn’t stand a chance with him. (She’s well played by Catherine Curtin, no relation to Jane.)

Reitman and his co-writer Gil Kenan are not reaching for anything profound in this film, which is probably a good thing. But I wish they had made more of a point of what a boys club, specifically a white boys club, this show was. Except for Shuster, none of the women in the movie are really given much of a voice, even in dissent. Morris, the only Black member of the cast, wonders aloud about his tokenism. He deserved more screen time. The film also whitewashes the behind-the-scenes drug use.

Reitman may also be making too much of this moment in TV history. “SNL” didn’t represent a cultural revolution exactly. Loving the show did not preclude its newfound adherents from also cherishing reruns of “The Dick Van Dyke Show” and “I Love Lucy” and all the rest. “SNL” was more like a recalibration of what television could offer. And it made it up as it went along.

“Saturday Night” also seems made up on the run, except, of course, its improvisatory tone is an illusion. At its best, the film demonstrates a showbiz truism: It takes a lot of hard work to make something look easy.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Saturday Night” is rated R for language throughout, sexual references, some drug use, and brief graphic nudity.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Roots of Mexico’s confidence against crime

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

What an entrance. On Tuesday, or only a week after she became Mexico’s first woman president, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo sent her security czar to walk the streets of Culiacán. The city is the epicenter of a murderous struggle between two factions of a giant drug cartel in the state of Sinaloa.

By his mere presence in one of Mexico’s most violent cities, Omar García Harfuch, the new secretary for federal public safety, was sending a nuanced message: Just as Mexico was able to make progress as a democracy in recent decades, it is now improving its approach to defeating organized crime.

Mr. García, a former police officer, was in Culiacán to show that President Sheinbaum plans to deploy some tactics that are different from those of her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador. While she will keep the crime-fighting social programs of AMLO (as the former president is known), she and her security chief will apply lessons they learned when she was mayor of Mexico City and he was head of the capital’s security. Together, they halved homicides in the city and suppressed many organized gangs.

Roots of Mexico’s confidence against crime

What an entrance. On Tuesday, or only a week after she became Mexico’s first woman president, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo sent her security czar to walk the streets of Culiacán. The city is the epicenter of a murderous struggle between two factions of a giant drug cartel in the state of Sinaloa.

By his mere presence in one of Mexico’s most violent cities, Omar García Harfuch, the new secretary for federal public safety, was sending a nuanced message: Just as Mexico was able to make progress as a democracy in recent decades, it is now improving its approach to defeating organized crime.

Mr. García, a former police officer, was in Culiacán to show that President Sheinbaum plans to deploy some tactics that are different from those of her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador. While she will keep the crime-fighting social programs of AMLO (as the former president is known), she and her security chief will apply lessons they learned when she was mayor of Mexico City and he was head of the capital’s security. Together, they halved homicides in the city and suppressed many organized gangs.

The new plan includes a focus on only six Mexican states – the ones with the most violent incidents. It also relies heavily on better police intelligence, mediation between cartels, and more coordination among security officials at all levels, from prosecutors to the military.

“Security is a problem that requires shared responsibility and a unified response,” the new president said in laying out her plan. Nearly two-thirds of Mexicans see public safety as the nation’s gravest problem, according to a government survey earlier this year.

Mexico, like many countries in Latin America, has been on a long learning curve in the battle against crime syndicates. Yet despite many setbacks, the region has a strong reason to believe it can someday succeed. Since the 1980s, most countries have successfully fought back against other powerful forces, according to two scholars writing in this month’s Journal of Democracy.

“Drug cartels and their bosses have replaced power-hungry generals, Marxist guerrillas, and predatory business elites as the forces most inimical to democracy,” wrote Javier Corrales and Will Freeman.

Building democracies to resist “nonelected threats” like generals, rebels, and elites once seemed improbable, they stated. Many countries still contend with those threats, but most of Latin America is now democratic.

“The lesson for today’s leaders is that institutional reforms can subdue security threats,” the two scholars concluded.

Mexico’s new leader is avoiding failed anti-crime policies and adopting different ones nationwide that have largely worked in the capital. For Mexicans, progress in their democracy has given them hope of making progress in upending a deep culture of organized crime. Good builds on good.

During his walk in Culiacán, Mr. García displayed that confidence in such progress. He has the people’s faith in rule of law behind him.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Is your battery drained?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Calder Ledbetter

If we’re feeling burdened or exhausted by the tasks on our plate, there’s help to be found as we look to God as the limitless, continuous, and self-sustaining source of wisdom, support, and care.

Is your battery drained?

Persistence, or the ability to “keep on keeping on,” is a good thing. But when it’s just willpower that is propelling our efforts, it can easily come up short. A September 2023 article I read on the Medium website talked about willpower in relation to a battery, calling it “a finite resource; one that could be spent only so much before it had to be recharged.” That’s a discouraging thought.

But Christian Science shows that we aren’t some kind of human battery that can power along only for a finite period of time. God is the source – and we are the effortless expression – of energy, strength, and stamina.

Recently I’ve been praying to better understand and put into practice what the Apostle Paul calls “patient continuance in well-doing” (Romans 2:7). While forced endurance and stress tolerance don’t cut it, “patient continuance” is the basis of real success, even in the face of obstacles. Getting a more accurate, more spiritual, understanding of our divine source is essential.

In my own life, I’ve drawn upon the idea of “patient continuance in well-doing” as a member of a student-run STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education program in my community. As part of my leadership position with the program, I not only design and teach STEM workshops, classes, and camps for local youth but also serve on a board, mentor junior members and volunteers, and model educational approaches for peers.

At the peak of my activity last fall, I felt like a drained battery. While I enjoyed the work, it felt unsustainable – and like a burden. This was when I realized I needed a more spiritual view. I didn’t want to give up this activity, but I did want to find peace.

One Sunday morning, as I was praying along these lines, the Christian Science Sunday School I attended opened with Hymn 320 from the “Christian Science Hymnal.” The hymn’s third verse immediately stood out to me:

Mere human energy shall faint,

And youthful vigor cease;

But those who wait upon the Lord

In strength shall still increase.

(Isaac Watts; arr. William Cameron, adapt.)

It occurred to me that my role was to “wait upon the Lord.” This involved listening for, and following, God’s guidance. This sounded a whole lot easier than trying to bear the false weight of personal responsibility and then trying to build up or find the energy to back it. Additionally, by waiting on God, we find that we have not only enough strength to carry out the tasks in front of us, but also the promise that our strength will continually increase.

This was a welcome reversal of the belief that our strength and energy must inevitably get depleted.

Mary Baker Eddy’s book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” the textbook of Christian Science, shares this related insight: “Let us feel the divine energy of Spirit, bringing us into newness of life and recognizing no mortal nor material power as able to destroy. Let us rejoice that we are subject to the divine ‘powers that be’” (p. 249).

One thing that I noted in the article I’d read online was that this battery concept was labeled as “Ego depletion theory.” But as children of God, we are all entirely spiritual and reflect God, who is the one Mind or Ego. So a human ego to be depleted isn’t even truly part of us. Our real source is God, who is infinite.

As I prayed with these ideas, I understood that I didn’t need an endless supply of willpower to carry out my activities. Instead, I could recognize that I reflect God. This was natural and effortless. Not long afterward, the feeling of burden lifted, and I was able to set a reasonable pace for my activity and find renewed stamina.

How freeing it is to realize that activity that involves waiting on God draws from the one perfect source, which never runs out and sustains us all.

Adapted from an article published in the July 29, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Beneath the pale moonlight

A look ahead

Thank you for engaging with the Daily today. For tomorrow, the set of stories that we’re working on includes a report from Florida as the powerful Hurricane Milton moves ashore. We’ll look at emergency responses by officials and the public.