- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for March 13, 2018

The United States has a new top diplomat, and we’ll get to that change in a moment. But here’s a longer-term shift that caught our eye: Between 2010 and 2015 the money held by women grew from 28 percent to 30 percent of all global wealth. That's modest progress that’s likely to continue, says the Boston Consulting Group.

Even more interesting is that women tend to make different moral choices – and often smarter ones – when they control the wealth, says a recent Economist article. Men tend to be overconfident. Women tend to seek advice, and they outperformed men in the markets by one percentage point each year, according to one study.

Here’s another difference: Women tend to care about others. Surveys show women want financial returns and social or environmental returns. For some wealthy women that means investing in women. They’re using a “gender lens” to choose stocks. While social investing has gotten a bad reputation for involving more risk and lower returns, that isn’t always true. Studies show that companies with more women in the top jobs perform better than those without. In fact, paying attention to gender equity is often an indicator of good company management.

Now to our five selected stories, reporting on what might be a voter shift on gun rights in Colorado, melding justice and motherhood in Costa Rica, and a new test of sustainable suburban living in the Sunshine State.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

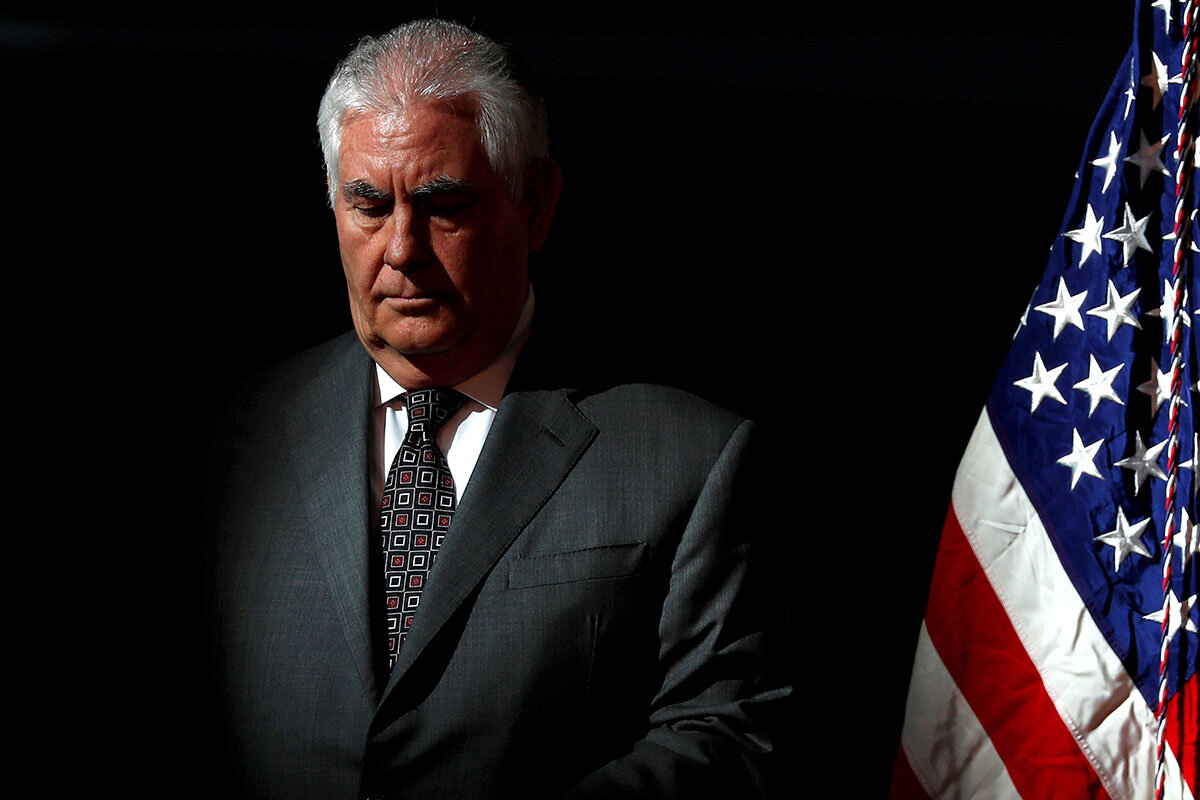

Tillerson ouster: Why top diplomat didn’t mesh with disrupter in chief

Relationships matter. The US secretary of State builds relationships with other nations. But the relationship between Rex Tillerson and his boss, President Trump, wasn’t on solid ground. That’s partly why the next top US diplomat will be someone with a closer working bond with the president.

The signs of a disconnect between a convention-scorning president and a business leader turned foreign-policy traditionalist had piled up over the past year. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson begged an annoyed President Trump not to move the US Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. The president ridiculed Mr. Tillerson’s insistence on diplomacy and reliance on sanctions to address North Korea. And perhaps most grating for Mr. Trump, Tillerson backed sticking with the Iran nuclear deal President Barack Obama had secured. Indeed some analysts say that it was very likely unreconciled differences over Iran that – along with the coming North Korea summit – spelled Tillerson’s unceremonious firing Tuesday. But it may also have been a matter of simple chemistry. “I think we’ve learned that this president requires … deferential treatment not just publicly but behind closed doors as well,” says Karl Inderfurth, who served in the Carter and Clinton administrations. “And it’s quite clear that Tillerson, while trying to establish a relationship with the president, never fully deferred to Donald Trump’s my-way-or-the-highway approach but saw it as his job to pursue America’s overarching diplomatic interests.”

Tillerson ouster: Why top diplomat didn’t mesh with disrupter in chief

In the end, Rex Tillerson was simply not enough of a disruptor to last as President Trump’s secretary of State.

Time and again over the course of Mr. Trump’s first year in office, his chief diplomat sounded a cautious and conventional note on foreign policy matters that the president had chosen as issues on which he could stand apart from the traditional approach to American statecraft.

The president who came into office on an anti-establishment wave seems to have realized fairly quickly that he had picked a solidly establishment secretary of State. But it wasn’t until Tuesday, a little over a year into his presidency, that Trump announced that Mr. Tillerson was out – to be replaced by CIA Director Mike Pompeo.

White House aides suggested the disruptor-in-chief wanted to make the change before embarking on perhaps his most unorthodox diplomatic initiative yet – a sit-down meeting “before May,” as Trump announced last week, with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

But the signs of a missed fit between a convention-scorning president and a business-leader-turned-foreign-policy traditionalist, who was informed of his dismissal while on an official tour of Africa, had piled up over the past year.

Tillerson begged Trump not to up-end an already fragile and torn Middle East by moving the US Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. An annoyed president dismissed Tillerson’s (and much of his national security team’s) concerns and forged ahead on the embassy move.

The president ridiculed Tillerson’s insistence on diplomacy – and a reliance on traditional pressure-intensification measures such as sanctions – to address North Korea’s advancing nuclear weapons and missile programs, publicly chiding his diplomat even as he was in Asia that he was “wasting his time” with talks.

And perhaps most grating for Trump, Tillerson backed sticking with former President Barack Obama’s signature foreign-policy achievement, the Iran nuclear deal, advocating working with European allies to strengthen the accord rather than simply jettisoning it.

Iran on his mind

Indeed some foreign policy analysts say that while the writing of Tillerson’s departure has been on the wall for some time, it was very likely unreconciled differences over the Iran deal that – along with the coming North Korea summit – spelled the top diplomat’s unceremonious firing.

“I don’t think people are giving enough weight to the differences over the Iran nuclear deal in explaining why, for this president, Tillerson had to go,” says Harry Kazianis, director of defense studies at the Center for the National Interest in Washington. “It’s been very clear that Trump has hated this deal since Day One and has been set on getting the US out – and yet there he was with a national security team, led by Tillerson and H. R. McMaster, that insisted on the disaster it would be to pull out every time the deal came up.”

In comments Tuesday on his snap decision to replace Tillerson with Mr. Pompeo, Trump made it clear that differences over the Iran deal were uppermost in his mind as he made a national security staff change that had been rumored for months.

“[Tillerson and I] disagreed on things [like] the Iran deal,” Trump told reporters as he departed the White House for a trip to California to tout his signature border wall project. “We were not thinking the same. With Mike Pompeo, we have a similar thought process.”

Trump went on to underscore his conclusion that Pompeo – who unlike Tillerson had publicly supported candidate Trump’s presidential bid – will be a better fit with his national security vision.

“I'm really at a point,” he added, “where we're getting very close to having the cabinet and other things that I want.”

Some analysts heard in Trump’s “very close” comment a hint that changes in the national security staff are not quite complete. Indeed Mr. Kazianis predicts that General McMaster, Trump’s national security adviser, is probably also not long for the Trump White House.

Still, for all his preference for anti-establishment thinking, Trump confirmed in making Pompeo his top diplomat an established truism about the secretary of State. Longtime diplomats and experts in American diplomatic history all say that the mark of a successful secretary of State is one who has the trust of the president and works well with him.

As Trump said Tuesday, “I've worked with Mike Pompeo now for quite some time… We're always on the same wavelength. The relationship has been very good, and that's what I need as secretary of State.”

Clearly Trump and Tillerson never established that critical “wavelength,” which experts deem essential.

Developing a rapport

“The key to the success and indeed the longevity of any secretary of State is his or her relationship with the president – and it’s very clear that rapport never developed between Donald Trump and Rex Tillerson,” says Karl Inderfurth, a former assistant secretary of State for South Asian affairs in the Clinton administration and a former White House national security staffer during the Carter administration.

On the other hand, Mr. Inderfurth says he has seen indications that Pompeo could be of the temperament to establish (or perhaps develop further) the all-important “rapport” with the president.

Inderfurth says he recalls being surprised when he came upon the CIA director on “Face the Nation” last Sunday. “My first thought was, ‘What the heck is the CIA director doing on a national news program discussing national security affairs, that’s very unusual,’ ” he says. “But then after getting over my surprise I was quite impressed by how deferential and really obsequious Pompeo was toward the president, how he kept repeating how on top of every issue the president is,” he adds.

“I think we’ve learned that this president requires that kind of deferential treatment not just publicly but behind closed doors as well,” Inderfurth says. “And it’s quite clear that Tillerson, while trying to establish a relationship with the president, never fully deferred to Donald Trump’s my-way-or-the-highway approach but saw it as his job to pursue America’s over-arching diplomatic interests.”

Whether Pompeo – a former Republican congressman from Kansas who displayed little use for his party’s internationalist foreign-policy mainstream – will fully jell with the president’s style remains to be seen. But analysts note that as CIA director he quickly adapted tasks like presenting the daily intelligence briefing in a manner that fit this president. And Pompeo seems to be on the Trump “wavelength” on key issues.

“Pompeo all along has been of the view that the Iran deal has got to go,” notes Kazianis of the Center for the National Interest.

What is unclear at this point is what stance Pompeo will take vis-à-vis Russia – whether he will fall in line with Trump in giving Russia a pass on its growing global aggressiveness (and specifically on interference in the 2016 election) or will stake out something of a more independent approach as Tillerson tried to do.

Final jab at Russia

Tillerson took one final swipe at Russia Monday – even as he returned from his shortened Africa trip – declaring Russia “clearly” responsible for a poison attack in Britain that targeted a former Russian spy who had turned Vladimir Putin critic.

Even though he knew he was finished in his job, Tillerson expressed solidarity with the British government – which earlier had hinted the attack could prompt an invoking of NATO’s Article 5, which calls for mutual defense among Alliance members. The attack would “trigger a response,” Tillerson told reporters aboard his return flight to Washington.

The final jab at Russia did not go unnoticed.

“Secretary Tillerson’s firing comes one day after he once again spoke out against Russia when the President would not,” said Sen. Chris Coons (D) of Delaware in a statement Tuesday. On Monday the White House – which Senator Coons said “has notably refused to address the real threats that we face from Russia” – pointedly declined to join British Prime Minister Theresa May in blaming Russia for the poison attack. Trump agreed in a phone call with Prime Minister May Tuesday that Russia must be held accountable for the attack.

Yet as important as the growing challenge posed by Russia may be, some analysts say it was more than anything Trump’s sudden decision to engage with North Korea – and a desire to have a national security team to his liking – that prompted Tillerson’s departure now.

“I think that once Trump made the decision to take on what may be the biggest superpower summit since the Cold War,” Kazianis says, “he also realized that he’s going to want around him a team that he knows he can trust.”

Share this article

Link copied.

For suburban GOP lawmakers, new pressure on guns

For at least two decades, rarely has a Republican challenged the National Rifle Association on gun rights. But in the wake of the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, one Colorado district may be indicative of a change afoot.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For years, conventional wisdom surrounding gun politics has been that it is a voting issue for those concerned about protecting Second Amendment rights, but not for those who favor more restrictions. However, there are signs that that may be changing. Public polling shows support for new gun control measures is at the highest level in years, with two-thirds of voters backing more restrictions. And of the 11 most endangered House Republicans, six have lately embraced new measures that would limit access to guns, according to a Reuters analysis. The issue is particularly resonant in this suburban Colorado House district, where, in 2012, James Holmes killed 12 people and wounded 70 at a movie theater. At a town hall meeting last month, one week after the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, incumbent Republican Rep. Mike Coffman found himself thrown on the defensive as emotional participants confronted him repeatedly over his stance on gun control and whether he would continue to accept campaign donations from the National Rifle Association. “People told me, ‘Don’t go up against the NRA and the gun lobby in a swing district,’ ” Mr. Coffman’s leading Democratic opponent, Jason Crow, said at a rally in Aurora. “But this is something I’m not afraid to lead on.”

For suburban GOP lawmakers, new pressure on guns

Colorado Rep. Mike Coffman (R) is used to tough campaigns. His suburban district east of Denver voted for President Barack Obama in 2012 and Hillary Clinton in 2016. Mrs. Clinton, in fact, beat President Trump in the district by 9 points – almost the same margin by which Representative Coffman beat his last Democratic challenger.

But at a town hall meeting last month, one week after the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, the Republican congressman found himself thrown on the defensive over gun violence. Emotional participants confronted Coffman repeatedly over his stance on gun-control legislation and whether he would continue to accept campaign donations from the National Rifle Association.

It’s a scene that’s playing out in a number of suburban districts across the country, where GOP lawmakers – already on shaky ground among their moderate, well-educated constituents, who tend to view Mr. Trump unfavorably – are seeing their political fortunes further complicated by the issue of guns.

For years, the conventional wisdom surrounding gun politics has been that it is a voting issue for those most concerned about protecting their Second Amendment rights, but not for those who favor more restrictions. For Republicans worried about a primary challenge, that has created little incentive to cross the NRA.

But there are signs that that may be changing. Student activists from Parkland have kept the issue front and center, demanding action – something that’s likely to continue with tomorrow’s national school “walkout,” and the march on Washington at the end of the month. Public polling shows support for new gun-control measures is at the highest levels in years, with two-thirds of voters now saying they would back more restrictions. And of the 11 most endangered House Republicans, six of them have lately embraced new measures that would limit access to guns, according to a recent Reuters analysis.

The issue is particularly resonant in this district, which is home to the Aurora movie theater where, in 2012, James Holmes killed 12 people and wounded 70 at a showing of “The Dark Knight Rises.” Columbine High School sits just a few miles away.

And while Coffman, who has an “A” rating from the NRA, hasn’t changed his position on guns, he “is being forced like never before to juggle and finesse the difficulties that are coming out of being a representative in Washington,” says Floyd Ciruli, a Colorado-based pollster. “My sense is the last blow is gun control.”

A bellwether district

Even before the gun issue gained prominence, Colorado’s sixth district was a top Democratic target. Almost evenly split between Republicans, Democrats, and independents, it’s exactly the sort of the suburban district that Democrats will need to win if they are to take back control of the House of Representatives this fall.

It’s “going to be a bellwether not only of this election but of broader trends in politics,” says Jason Crow, the leading Democratic challenger to Coffman.

As a candidate, Mr. Crow embodies many of the qualities the national Democratic Party is looking for in candidates they hope can win back Republican seats. He’s a veteran – a former Army Ranger who served in Iraq and Afghanistan – who has been active in veterans’ affairs. He has blue-collar roots. He’s an affable family man with young kids. Most important perhaps, in the current climate: He’s a political newcomer.

“Coffman is not a new target for Democrats, but Democrats have just never been able to crack the code,” says Nathan Gonzales, editor of the nonpartisan Inside Elections newsletter. “The key is that the environment should be much better than when they’ve tried to target him in the past.”

In order to keep his seat as the district has trended more Democratic, Coffman has moderated some of his political stances from when he was first elected. He’s done outreach to minority communities and immigrants. In 2016, he ran an ad touting his service as a Marine and promising voters he would stand up to either Trump or Clinton, regardless of who was elected. (He even released a Spanish-language version of the ad targeted at the district’s 20 percent Latino population.)

Many independents in the district may have split their vote, say experts, both because Coffman was a known quantity they liked, but also in expectation that Clinton would win the election and he would help provide balance in Washington.

Now, with Trump in power, that’s a harder argument to make. “Trump is toxic among Democrats and also pretty unpopular among Independents,” says Seth Masket, a political scientist at the University of Denver. Being part of the Republican Party “makes it harder for Coffman to portray himself as someone independent of who the president is.”

At a recent Crow rally in Aurora, that dynamic was in full force, with plenty of emphasis on how much Coffman’s voting has aligned with Trump’s agenda.

“I think Coffman has been a good campaigner, but he goes to Washington and votes 95 percent with Trump. He speaks out of both sides of his mouth,” says Mark Kastler, attending the rally with his wife. Mr. Kastler is from the solidly red town of Centennial, and says he doesn’t expect many of his neighbors to vote against Coffman, but he has hopes that Crow’s status as a former Army Ranger will “neuter Coffman’s perennial appeal to having been a combat veteran.”

Taking on the gun lobby

Significantly, almost all the speakers at the Crow rally talked about gun control – eliciting more cheers than perhaps any other topic.

“People told me, ‘Don’t go up against the NRA and the gun lobby in a swing district,’ ” Crow told the crowd, citing the town hall at which Coffman dismissed those who showed up as “the angriest voices.” “I’m here to tell you that Mike Coffman has made a big mistake.”

“My son is a police officer here,” says Kellie Wagner, a bank worker in Aurora who attended Coffman’s town hall meeting as well as the Crow rally. She says she asked Coffman what he would do to protect her son and other officers from the kinds of shootings Aurora police have faced lately, and didn’t get a satisfactory answer. “If he had said, ‘I won’t take any more NRA money,’ so many people would have applauded,” Ms. Wagner says.

Crow acknowledges that gun control can be a tricky topic to wade into in a state with a long history of gun ownership. “Conventional wisdom is not to [talk about it],” says Crow, noting that his campaign put out a digital ad on the issue last month. “But this is something I’m not afraid to lead on.”

And Crow’s biography – both as someone who grew up hunting and someone who fought in Iraq – gives him substantial credibility. “I know something about firearms,” he says. “My right as a hunter would not be impacted in any way by all the common-sense reforms we’re talking about.”

It’s too soon to know whether gun control will still be as top-of-mind for voters in November. Certainly, electoral history would argue against it. But for now, Democrats point to a recent poll that shows Crow running ahead of Coffman 44 to 39. It’s a small poll from a Democratic polling firm, and early in the race, but analysts say it’s the first public poll of any kind they can recall showing a challenger ahead of Coffman in the past 10 years.

“Coffman has had hard races in the past, but this is his hardest one,” says Kyle Kondik, managing editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, the University of Virginia’s nonpartisan elections newsletter. “It’s a legitimate tossup race, as it has been in the past – but it’s maybe the toughest environment he’s had to run in.”

Doing time along with Mom: a cruel sentence or a child's right?

When a mother goes to jail, should her child join her? There are no easy answers to the moral, educational, and safety concerns raised by this question. About half the countries in the world say a mother’s love trumps all other concerns. Our reporter looks at how Costa Rica handles this issue.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A young boy scrambles on the orange-tile floor, grabbing for his paper airplane. Above him an eager playmate lets out a shriek, trying to wiggle his way out of his high chair. Mothers and children share food and soft drinks and rock babies in strollers, while some eye news on the flat-screen TV. This is a Costa Rican prison. Like an increasing number of prisons across the world, it’s a home for not only incarcerated women, but their babies, too. Young children are better off bonding with their parents, even if they have committed a crime, defenders of the practice say. They argue that children’s rights are better supported by keeping them with Mom or Dad. But it’s a controversial approach, raising tough questions about safety, justice, and sacrifice. Should children have to “serve” a parent’s sentence? Does a childhood in prison encourage cycles of crime and poverty or break them? “When a child is old enough, you have to tell her the truth,” says one inmate. “Your mother made a mistake.” Her toddler lives with her in prison, though her 5-year-old daughter does not.

Doing time along with Mom: a cruel sentence or a child's right?

From the pint-sized toilets to the colorful bedrooms and backyard filled with overturned tricycles, there’s no question children live here.

What’s less obvious is that the 38 babies and toddlers bunking with their mothers at the Vilma Curling Rivera Institutional Service Center are in prison.

Their mothers are serving time for crimes from fraud, to drug dealing, to robbery – but also devoting time to nap schedules and potty training. As one mother makes funny faces to a scrum of giggling toddlers in the common area, another, Magela (who asked to withhold her full name for her family’s privacy), is putting her young daughter down for a nap. The walls of the bedroom are almost entirely covered by tapestries depicting children’s movie characters, like Elsa from “Frozen.”

“It’s hard to be here with my daughter, but amid all the bad, she gives me hope,” says Magela. She’s been here for six weeks with her 1-year-old daughter while awaiting sentencing on human trafficking charges.

Across Latin America and much of the world, it’s increasingly common to find mothers and their children together behind bars. Although rare in the United States, the practice stems from the perspective that young children are better off bonding with their mothers (and in some prisons, like in Bolivia, with their fathers), even if they have committed a crime. But it raises tough questions about safety, justice, and sacrifice. Should children have to "serve" a parent’s sentence, for example? Is a motherless childhood better than one in prison? And does spending time in prison at a young age encourage cycles of crime or poverty, or break them?

Increasingly, the practice is viewed through a human rights lens – with the focus on the rights of the children.

“In prison, the presence of a child is the child’s right – to be with his mother, to breastfeed, to meet essential development needs,” says Kenly Garza, assistant director of the Vilma Curling Rivera prison.

In Costa Rica, children are allowed to live with their mothers for the first three years of their lives. In Mexico, children can stay with their mothers until they are 6 years old. In Afghanistan, a child can famously languish in prison with her mother until she’s 18. Roughly half the countries in the world allow mothers serving a sentence to live with their children, if only for a few months, according to a 2014 Library of Congress report.

“There are some who think this is a good thing, and some who see it as bad,” says Ms. Garza. “But in most cases, opinions are based on stereotypes. If you’re in prison, you’re automatically [labeled] a bad mother.”

'I'd go crazy without her'

A young boy scrambles on the orange-tile floor, grabbing for his paper airplane, on a recent morning at Vilma Curling Rivera. Above him an eager playmate lets out a shriek trying to wiggle his way out of his high chair. Mothers and children sit along the periphery of the common area, sharing food and soft drinks, rocking babies in strollers, and some eyeing news of snow in Europe on the flat-screen TV.

Under Costa Rican law, children don’t spend their entire day in prison; they’re sent to off-site day care for several hours. Nongovernmental organizations teach mothers parenting skills and work on personal goal-setting and development.

Lady, who also asked not to use her surname, was pregnant when she was sent to prison five months ago on fraud charges. That meant living with the general prison population, who sleep in tightly squeezed rows of bunk beds. She had 50 roommates at the time. Once her now four-month-old daughter was born, she was moved into a private room with a crib, and neighbors who instantly had something in common: motherhood.

“It’s definitely nicer here,” she says of the children’s area, its own building in the low-slung prison complex. “I think I’d go crazy without her,” she says of her daughter. “I think I benefit most from having her here.”

Critics say perks like a private room or the constant companionship of a child will incentivize more inmates to get pregnant. Garza says evidence doesn’t back that up – the population of mothers with children has remained steady over the past several years. Others argue prison becomes less of a punishment when family is permitted to join those serving time, that committing a crime punishable by prison makes a mother unfit, or that it’s an inherently harmful place to grow up.

“The children might be exposed to bad language, sometimes there’s aggressive behavior [among inmates],” says Isabel Gámez Páez, who runs programming for women in prison in Costa Rica’s Ministry of Justice. She argues prisons need to be redesigned overall to better accommodate the unique needs of women, including motherhood.

But the reality is that children are often better cared for in prison – where meals are guaranteed and an adult is always present – than on the outside, Garza says.

The majority of women in prison in Costa Rica are there for drug-related crimes, like small-scale trafficking, an offense that research suggests is frequently motivated by a lack of employment opportunities, poverty, or coercion by family or romantic partners. A 2010 study found that 95 percent of women in jail for bringing drugs into prisons in Costa Rica were single mothers. Often, when women go to prison their dependents are put at risk of falling deeper into poverty, or taking part in criminal acts as well, experts say.

Improving the system

For cases where children do end up behind bars with their mothers, there are best practices around the world that could be applied elsewhere, experts argue. In Norway, for example, children aren’t allowed to live in jail, but they can visit three times a week and call at any time. They also have modular homes, outside of the prison, where incarcerated mothers can visit with their kids.

Alternative sentencing for non-violent crimes and low-level drug violations could also balance the tension between serving justice and the needs of a minor, writes Fabiola Mondragón, a researcher at the Mexican think tank CIDAC, in a 2017 opinion for news site Animal Politico.

That’s a relatively new process in Costa Rica, where women who have trafficked drugs into prisons and who come from vulnerable backgrounds – like caring for dependents alone – have the chance to go to rehab and serve community service instead of going to jail.

“A mother is a figure you can’t substitute in the life of a child,” says Magela, her young daughter crawling cautiously under an empty high chair. “They are tiny. Being here as an infant isn’t so traumatic. The separation would be far worse.” She has experience with that as well: her 5-year-old daughter isn’t living with her here, though she can visit frequently.

“Right now I’m vague [when telling my older daughter] about where I am. But when a child is old enough, you have to tell her the truth: Your mother made a mistake.”

In the Sunshine State, a vision for a sustainable town

Can suburbia be the cutting edge of sustainability? Our reporter visits Babcock Ranch, where a Florida developer just opened the first phase of an eco-friendly solar-powered community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Florida has no shortage of planned communities. But one development sprouting up in southwest Florida is markedly different. At Babcock Ranch, developer Syd Kitson set out to build more than a town. “We wanted to prove that environmental responsibility can go hand in hand with development,” says Mr. Kitson. So far, only a handful of families have moved into the town, which celebrated its grand opening on Saturday, But interest has been high, Kitson says, with about 1,000 weekly visitors. The most visible of the town’s sustainability efforts are the encouragements to drive less. Kitson envisions residents walking, cycling, and hailing rides from an electric-powered, self-driving shuttle. Many green urban planners remain skeptical that Babcock Ranch will be able to become the kind of eco-haven that Kitson is proposing. Any new development is going to leave a mark on the environment. And many residents are going to rely on cars to commute out of town for work and other reasons. But for some, Babcock Ranch is a valuable experiment in green suburban living.

In the Sunshine State, a vision for a sustainable town

Children play in a fountain as their parents watch from the shade of a palm tree. Friendly chatter emanates from a nearby restaurant. Downtown Babcock Ranch, Fla., seems much like the center of any other small town.

And yet green-stemmed solar “trees” dot the landscape. A driverless red pod buzzes down the street. And the old-timey general store is powered by the sun.

Babcock Ranch may resemble the towns of the past, but developer Syd Kitson built the community for a sustainable future. This marriage of conventional development and eco-friendly innovation offers a more traditional model of sustainability. Many green urban planners remain skeptical that this experiment in sustainable living will be able to achieve the kind of eco-haven that Mr. Kitson is proposing. But for some, Babcock Ranch is a step in the right direction.

“We wanted to prove that environmental responsibility can go hand-in-hand with development,” Kitson says.

Babcock Ranch, which currently looks like a town center protruding from an otherwise empty prairie, held its official grand opening March 10 but it has yet to incorporate. The plan is for some 19,500 homes to be constructed, but today there are just a handful, and only a few of those are occupied. The rest of the lots are filled with sparse grass and fire ants, awaiting backhoes.

But the town square is already active, with the restaurant, general store, and ice cream shop seeing new customers daily. Kitson estimates that curiosity has brought about 1,000 visitors a week.

“I think we’ve struck a chord with people," Kitson says. “And that’s starting to translate into people wanting to live here.”

Curbing cars

The most visible of the town’s sustainability efforts are the encouragements to drive less. Although just one electric-powered, self-driving shuttle navigates the streets on a trial basis now, the plan is for a fleet of the red pods to follow set routes and be summonable via smartphone. The town was also designed with walkability in mind, with residential streets all within walking distance from the town square. Bike shares offer another transportation option.

Steve Wheeler, a professor in the landscape-architecture program of the department of human ecology at University of California, Davis, doubts that Babcock Ranch will be able to get people to completely eliminate their cars.

“One basic problem is location,” he says. With the nearest city, Fort Myers, about 15 miles away, people will still travel outside of the town for their jobs and other resources, despite the fiber-optic internet service and coworking space in the town center.

For this reason, cities have often been held up as having the smallest environmental footprint. Urban-dwellers share resources, drive less, and take up less land.

So, Wheeler says of Babcock Ranch, “It will be a model of moderately better suburban development. I hand it to the developers for trying to improve on conventional models.” But he suggests building eco-friendly communities onto existing urban centers might be be the best way to develop sustainably.

But, says Steve French, dean of the College of Design and a professor of City and Regional Planning at Georgia Institute of Technology, “Not everybody wants to live in Manhattan-scale density. So I think sustainability principles have got to be applied to suburban kinds of situations.”

Powering a city

Historically, so-called eco-cities have aspired to be independent from the utility grid, something that utility companies have fought. But Babcock Ranch works within the system, drawing power primarily from Florida Power & Light's 75-megawatt solar farm, to which Kitson donated 440 acres. The city also supplements this power with small installations like the solar trees.

“It is somewhat realistic in that it does tie into the existing grid and works with the existing utility,” says David Hsu, assistant professor of urban and environmental planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Solar panels work only when the sun shines. When it’s cloudy or nighttime, Babcock Ranch draws its power from the utility’s conventional sources. In Florida, most electricity is generated from natural gas.

The town could further reduce its dependence on fossil fuels, as Florida Power & Light announced March 9 that it is beginning to install batteries at the Babcock Ranch solar field.

Making sustainability a habit

Kitson’s vision was also to build sustainability into the infrastructure. That meant requiring home-builders to install efficient windows and insulation, efficient heating and cooling systems, and energy and water saving appliances. All houses built in the community must achieve no less than a Bronze rating from the Florida Green Building Certification.

Irrigation is done with recycled water, and community gardens are sustained with collected rainwater. Landscaping around town predominantly uses native plants that are adapted to survive mainly off the amount of rain that falls in the region.

The curriculum at Babcock Neighborhood School, which opened in the fall of 2017 as a public charter school open to surrounding communities, focuses on instilling sustainability and conservation principles through project-based learning, too.

It’s this mentality that attracted the Vokaty family. Kelli da Silva Vokaty and her husband and two daughters originally had no plans to move from their home in Pembroke Pines, Fla. But when Mrs. Vokaty saw a television report about “the first solar-powered town in America,” the family made plans to check it out. Less than a week later, the Vokatys were sold on Kitson’s vision, and had put a down payment on one of the model houses there, with plans to move in two years.

Vokaty says she had a lifelong love for nature, and hopes to further instill eco-friendly habits in her children. “I want them to make a difference for their generation,” she says.

Points of Progress

The shift in attitude that’s sending stolen artifacts home

This story is less about guilt than about an evolving sense of global justice: the art-collecting world is making amends for old cultural thefts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Husna Haq Correspondent

France, home to thousands of plundered artifacts in museums and private collections, added momentum this month to a trend that has accelerated over the past decade. President Emmanuel Macron announced the appointment of two experts to craft plans for the return, over the next five years, of African artifacts held in French museums. The move followed a November speech in which he said, “African heritage cannot be a prisoner of European museums.” After centuries of cultural theft, the pendulum may be swinging toward repatriation, thanks to increased awareness of past cultural injustices and renewed respect for national sovereignty. Venezuela returned to Costa Rica 196 pre-Columbian artifacts; Canada returned to Bulgaria an antique Cretan sword and dagger. Last year craft company Hobby Lobby returned to Iraq 5,500 artifacts, including ancient cuneiform clay tablets smuggled out in 2009. Such moves, like Mr. Macron’s pledge – and the overwhelmingly positive reaction to it – may be evidence of a generational shift in attitudes on repatriation, says an expert on art and ethics at the University of Denver. “[It] provides a sense of belated justice for past human rights and cultural abuses,” she says. “It’s more than a legal matter of who has clear title. It’s a moral issue.”

The shift in attitude that’s sending stolen artifacts home

In June 2013, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned to Cambodia two 10th-century sandstone statues, originally looted in the 1970s by the Khmer Rouge.

In July 2017, craft company Hobby Lobby returned to Iraq 5,500 artifacts, including ancient cuneiform clay tablets, illegally smuggled out of the country in 2009 and camouflaged as tiles.

In October 2017, France returned to Egypt eight 3,000-year-old statuettes illegally smuggled out of the country and seized by French authorities at a Paris train station.

After centuries of cultural theft, the pendulum may be swinging toward repatriation.

It’s a trend that has accelerated over the past decade, thanks to increased awareness of past cultural injustices and renewed respect for national sovereignty, some experts say.

On March 5, France, home to thousands of plundered artifacts in museums and private collections, added fresh momentum to the trend.

In a joint appearance with President Patrice Talon of Benin, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the appointment of two experts to craft plans for the return of African artifacts held in French museums, echoing a November speech in which he said, “African heritage cannot be a prisoner of European museums.”

His bold pledge to return African artifacts in the next five years – and the overwhelmingly positive reaction to it – may be evidence of a generational shift in attitudes on repatriation, says Elizabeth Campbell, director of the Center for Art Collection Ethics at the University of Denver in Colorado. “[Repatriation] provides a sense of belated justice for past human rights and cultural abuses,” she says. “It’s more than a legal matter of who has clear title; it’s a moral issue.”

This growing awareness “has made the topic of return and restitution one of the main concerns of this age and a priority for UNESCO’s member states,” says Edouard Planche, a heritage specialist with the organization.

In 1970, UNESCO created a treaty designed to curb the transfer of stolen cultural goods. As a result, many museums will now display pieces purchased before 1970 and return objects acquired after. Since the convention, a number of national and international databases to track stolen art and artifacts have also been created, including an INTERPOL database, the Lost Art Database, and the National Stolen Art File.

Data on global repatriation is scarce, but progress is evident. Since 2007, the United States has returned more than 8,000 stolen artifacts to 30 countries, including paintings from Poland, manuscripts from Peru, and dinosaur fossils from Mongolia, according to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Of course, the trend extends beyond US borders. In January, Venezuela returned to Costa Rica 196 pre-Columbian artifacts; in January 2016, Canada returned to Bulgaria an antique Cretan sword and dagger; and in July 2015, Canada returned to Lebanon an ancient Phoenician pendant dating back to 600 BC.

And while the artifacts are cultural treasures, the symbolism is often as important, adds Julia Fischer, a professor of art history at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas. “Getting these objects back would be a symbolic win for [the countries] and proclaim that they are no longer victims of colonialism but are independent nations.”

Of course, challenges – and critics – are plentiful.

A United Nations report issued in 2012 evaluating the effectiveness of the 1970 convention found it to have “serious weaknesses,” including a lack of staffing, resources, and laws to back it up.

The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the rise of Islamic State in Syria and Iraq “ushered in a new period of illicit trafficking of objects from the Middle East,” says Professor Campbell. In response, the UN in February 2015 approved a resolution calling for countries to take steps to prevent trade of stolen Iraqi and Syrian property.

And the debate on repatriation is by no means settled, with some critics questioning whether countries of origin necessarily have the resources for proper care and preservation.

For many of the people to whom these artifacts arguably belong, however, the debate is moot.

“As Iraqis, these monuments mean a lot to us,” says Yazan Fadhli, an Iraqi who worked as a linguist for the US during the most recent conflict. After years of unrest in Iraq, “It’s something that helps us forget what divides us ... and gives us hope and confidence and motivation to build back our country again.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Take the taint out of March Madness

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

March Madness, the college basketball championship tournament, is under way. It’s a stunning exhibition of athleticism and competitive desire that will serve up pageantry and surprises from now until April 2. But beneath the glamour lies a sport that makes a mockery of the amateur-student-athlete ideal. For some time the FBI has been looking into illegal payments made to college basketball players and their families. So far, 10 individuals, including four active college assistant coaches, have been arrested. But this likely represents only a tiny fraction of the extent of the problem. Proposed solutions include offering college players legal ways to profit from their skills. But such schemes eat away at the concept of amateurism. The best solution could come from the National Basketball Association. It could lower the age limit to 18, allowing the very best high school players to be drafted directly into the league. It could also beef up its G League, a developmental league for prospective NBA players. What could emerge from such moves: a more honest system in which top teen players could choose between the advantages of “going pro” or going to college on a scholarship. College basketball would still be entertaining. The pressure to cut secret, illegal deals would be greatly reduced.

Take the taint out of March Madness

March Madness, the college basketball tournament, dazzles fans with tradition and pageantry, unexpected heroes and goats, and memorable moments. This stunning exhibition of athleticism and competitive desire will dominate American sports from now until the April 2 championship game.

But beneath the glamour of big-time college basketball lies a sport clad in the tatters of disgrace, one that makes a mockery of the amateur student-athlete ideal.

For some time the Federal Bureau of Investigation has been looking into illegal payments made to college basketball players and their families. So far 10 individuals, including four active college assistant coaches, have been arrested. But this likely represents only a tiny fraction of the extent of the problem. By one estimate at least 50 college basketball programs eventually may be found to be compromised.

What motivates the rule-breaking? The billions of dollars of profits at stake for major universities, athletic gear companies, and TV networks.

Despite the huge amount of money involved, very little of it goes to the players themselves, whose skills are at the core of the whole enterprise. To players interested in receiving a college education, an athletic scholarship does offer a sizable financial enticement. But many top high school players are either not qualified for or uninterested in college academics. For them, playing college basketball provides only one incentive: a way to showcase their skills to professional scouts with the hope of someday playing in the National Basketball Association or in a professional league overseas. (Only a tiny fraction of high school players eventually are drafted by an NBA team, according NCAA statistics: 0.03 percent, or three out of every 10,000.)

The NBA requires that players be at least 19 years old and one year out of high school to enter the league. That forces top teen players to play college ball for a year after high school, creating what’s known as the “one and done” phenomenon: players staying a single year (and attending classes during their first semester just to remain eligible to play).

College programs compete intensively for these prized players, which has inevitably led some to go beyond what is legal in offering “under the table” incentives.

The economics at play are simple: Top players have considerable financial value beyond what they are being paid (even with scholarships). One set of solutions would be to offer college players legal ways to profit from their athletic skills. They could be given stipends for living expenses beyond their academic scholarships, literally amounting to modest paychecks. They could be allowed to endorse products, such as athletic shoes, for pay. One coach argues they ought to be able to take out loans against their future professional earnings.

But all these schemes eat away at the concept of amateurism in college athletics.

The best solution could come from the NBA. It could lower the age limit to 18, allowing the very best high school players to be drafted directly into the league. It could also beef up its G League, a developmental league for prospective NBA players. Teens looking for a career in pro basketball could be drafted straight into the G League to develop and showcase their skills.

Right now, the NBA has little incentive to improve its obscure G League because colleges provide what amounts to a free minor league that develops players. G League salaries are as low as $20,000 per season (the NBA’s minimum salary is $562,493 per season), and the games are much less visible on TV than top college contests. Today’s top prospects would much rather spend a year in college than head into a year of G League basketball obscurity.

Better G League TV contracts and playing in bigger arenas in front of bigger crowds could change that calculation. And colleges might have to include a stronger message about the life advantages of obtaining a college education in their recruiting strategies. What could emerge is a more honest system in which top teen players could choose between the advantages of “going pro” or going to college on a scholarship.

College basketball and March Madness would still be entertaining, filled with plenty of highly skilled players who either don’t quite have NBA-level ability or who truly want a four-year college education.

The pressure to cut secret, illegal deals with college players would be greatly reduced. And college basketball could become a more authentically amateur college sport.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

To find what the world is trying to be

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Thomas Johnsen

Today's column examines our role as individuals in building a just society and healing a world in great need.

To find what the world is trying to be

“Your job is to find what the world is trying to be.”

It’s a line from a poem titled “Vocation,” by the American poet William Stafford. The poem, which is unflinchingly frank about troubled family relations, describes the “dream the world is having about itself” and hints at glimpses that “tell something better about to happen.”

The mission to find what a troubled world “is trying to be” isn’t just for poets. It could also apply to journalists – and, in a compelling sense, to the mission of The Christian Science Monitor.

The purpose of the Monitor reflects the ethic and values of the church which publishes it. Mary Baker Eddy, who established both the newspaper and the Church of Christ, Scientist, summarized this ethic in the first issue in 1908: “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 353).

The Monitor isn’t intended to propagandize for a religious doctrine or a partisan political position, but its purpose flows from the denomination’s basic Christian commitment to minister to the needs of humanity – to be a genuine healing influence in the world.

A newspaper addresses thought. It speaks to the consciousness and conscience of society. And consciousness determines the direction in which history will go. As the late Czech President Václav Havel pointed out, for example, the astonishingly peaceful revolution that ended totalitarian domination of his country took place first in the consciousness of ordinary citizens. The outward change in society resulted from a change in the people’s thought.

The Monitor’s founder took a similar view. The healing of society – like healing of the body in the serious ministry of prayer, as she held – comes fundamentally through awakening in thought.

In her early years, she witnessed the profound sea change in human attitudes that led to the abolition of slavery in the United States. “The history of our country, like all history,” she wrote, “illustrates the might of Mind” – the power of God – “and shows human power to be proportionate to its embodiment of right thinking” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 225).

“Right thinking” here doesn’t mean a particular set of opinions. Eddy stated bluntly, “In Christian Science mere opinion is valueless” (Science and Health, p. 341). The charged intensity of political opinions often inflames divisions and confines the thinking of whole groups within narrow prejudices. The effect is mesmeric. In today’s polarized world, it takes serious moral effort to come out from the grip of strong personal opinion and recognize the “image” of God – the spiritual likeness or expression of divine Love – reflected in those with whom we differ.

This is the spirit to which the Monitor calls its readers as well as its journalists. There’s nothing saccharine in this commitment. It isn’t about avoidance of evils or merely “looking for the positive.” In reporting on social and political issues, the newspaper strives to keep in focus what is ultimate and lasting, what actually redeems and heals. In responding to these issues, readers are challenged to lift their own sights beyond personal self-concerns to a broader vision of humanity – and of their own indispensable role as individuals in building a just society and healing a world in great need.

In a discouraging time for the people of Israel, the prophet Habakkuk caught a glimpse of the illumined spiritual relation of God to the whole of creation: “For the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea” (Habakkuk 2:14, New King James Version). The prophet’s reference to the knowledge of God’s glory is significant. Our need isn’t for God’s glory, God’s kingdom, to be more present than it already is. Our need is to know this divine reality and to let it inspire our thoughts and actions. The salvation Habakkuk is pointing to is first and foremost an inward change, beginning in individual hearts but reaching to all humanity.

To “find what the world is trying to be” begins with understanding the world as it actually is. Today’s prevalent materialism isn’t the exhaustive realism often presumed; it misses the spiritual heights and depths in human experience. Neither (as this newspaper’s founder insisted) is the biblical recognition of “true humanhood” in the spiritual image of God a backward-looking religious ideal.

What the image of God is includes and transcends the best of what humanity is “trying to be.” It is what each of us already and always is in the light of divine Love. This insight changes the world as it transforms humanity’s understanding of itself. It brings to light possibilities for genuine healing and progress in society that are urgently needed – and powerfully practical – in these tumultuous times.

Adapted from an editorial in the October 2017 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

Busing the besieged

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We're working on a story about why some high-tax states in the US are concerned that some of their wealthiest residents may move.