- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Gaza and Jerusalem: Assessing the real costs of 'no-cost' US diplomacy

- New push on immigration roils midterms – and House Republicans

- Life on a volcano: Hawaiians face Kilauea eruption with reverence

- In Nigeria, an ethical struggle at the heart of a medical strike

- For women in law, 'RBG' is their superhero movie

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for May 15, 2018

'Tis the graduation season, a time to celebrate educational achievement – especially among those who really persisted.

Take the mother and son who graduated together this month from Broward College in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Kenneth McCray’s father died when he was 6. His mother was diagnosed with cancer three years later. He left college to help pay the bills after she lost her job in 2012. For two years they were homeless. But today, Patricia Love Davis is healthy and has a degree in criminal justice. Her son received his computer science degree on the same day.

“Two things my parents and grandparents instilled in me: God will never put you through more than you can handle, and this, too, shall pass,” said Ms. Davis.

Annie Watts offers another portrait of perseverance.

She dropped out of school in seventh grade to escape a violent household. Most of her life, Ms. Watts was told that she was ignorant. “It don’t make you feel good when people tell you that,” she told WAFF-TV in Huntsville, Ala.

But at age 70, she hit the books again and got her GED. Last Friday, the 75-year-old grandmother walked across the stage with an associate degree from Drake State Community and Technical College. Her favorite Bible verse was written on her mortarboard: “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

Now to our five selected stories, including a look at resilience in Hawaii, the ethics of a healthcare strike in Nigeria, and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg as pop star.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Gaza and Jerusalem: Assessing the real costs of 'no-cost' US diplomacy

The optics were awful. Even as VIPs in Jerusalem dedicated the relocated US Embassy, Israeli soldiers killed dozens of Palestinian protesters in Gaza. But beyond the timing, the partisan nature of the move has broader implications for Mideast peace and US diplomacy.

The relocation of the US Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem reverses decades of policy from Republican and Democratic administrations alike. And it puts an already moribund peace process in even deeper peril – if it doesn’t simply end prospects for negotiations under this American administration, some regional experts say. The move has undermined US reliability in the eyes of Arab allies, while European partners see a unilateral decision that further destabilizes an already conflict-ridden region. Even as embassy dedication speakers lauded the move as an expression of peace, Palestinian protesters in Gaza were being repelled with Israeli soldiers’ live fire that killed more than 55 by the end of the day. But to a wide range of analysts, perhaps the most disconcerting consequence is how it has accelerated the transformation of Israel into a partisan issue in the United States. Says David Halperin of the bipartisan Israel Policy Forum, which supports a two-state solution: “Until recently there was no divide in our support for Israel, but the spectacle of a very partisan embassy dedication ceremony Monday only underscored how Israel is becoming just another piece of the partisan fight that engulfs our country.”

Gaza and Jerusalem: Assessing the real costs of 'no-cost' US diplomacy

President Trump has boasted to spirited applause at political rallies over recent weeks that his good sense as a businessman allowed him to move the US Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem for a fraction of the billion-dollar cost diplomats predicted.

As if to underscore the low cost of the move, the 800 invitees to Monday’s dedication ceremony at what until now was the US consulate in Jerusalem were served pretzels and water – nothing more.

Of course when the United States gets around to constructing a new embassy building in Jerusalem to replace the old one in Tel Aviv, the price tag will no doubt approximate the $1 billion experts have ball-parked since Mr. Trump announced the controversial move in December.

But the real and long-term costs of a move that reverses decades of policy from Republican and Democratic administrations alike – and which flies in the face of US-led regional peace efforts – are likely to be measured in repercussions that go beyond a few cases of bottled water and bags of pretzels, many Middle East experts say.

The embassy move certainly puts a peace process already on life support in even deeper peril, if it doesn’t simply end prospects for a return to negotiations under this American administration, some regional experts say.

Some of America’s Arab allies – and in particular Jordan and Egypt, which are among the most loyal (but also most dependent) – are less sure of the reliability of relations with the US, others add. And European allies, they say, see the US embassy move as another unilateral Trump decision on the international stage that further destabilizes an already conflict-ridden region.

And perhaps the most disconcerting consequence a wide range of analysts see not just from the embassy move itself, but in the way it was carried out, is how it has accelerated the transformation of Israel into a partisan issue in the US.

“Until recently there was no divide in our support for Israel, but the spectacle of a very partisan embassy dedication ceremony Monday only underscored how Israel is becoming just another piece of the partisan fight that engulfs our country,” says David Halperin, executive director of the Israel Policy Forum, a New York-based bipartisan organization that supports securing Israel’s future through conclusion of a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“That should be a very worrisome development for anyone, like us, who supports a strong Israel – unless in fact you see this kind of cost as a gain, as the Trump administration seems to,” he adds.

In Gaza, deadly clashes

Indeed, the costs of a foreign-policy decision that supporters laud as bold and morally courageous, but which detractors fault for exacerbating Middle East tensions for the sake of fulfilling a campaign promise, are already piling up.

Even as speakers at Monday’s embassy dedication lauded the embassy move as an expression of peace, Palestinian protesters less than 50 miles away along the Israel-Gaza border were being repelled with Israeli soldiers’ live fire and tear gas. By the end of Monday more than 55 protesters had been killed.

The violent demonstrations continued Tuesday, as Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank marked the 70th anniversary of the Nakba, the expulsion and flight of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homes in the newly declared state of Israel.

But the repercussions of the US embassy move to Jerusalem are likely to continue well after the violence dies down.

Trump continues to say he wants to achieve “the greatest deal of all” by securing peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. But a move that disrupts further a teetering balance by putting the US even more solidly on one side in the conflict sinks deeper the traditional role the US has played as an “honest broker” in peace talks – and makes achieving Trump’s “ultimate deal” even less likely.

Among US allies and partners, the embassy move was met with nearly unanimous negative reaction. Most nations keep their embassies in Tel Aviv, as the US did until Monday, in international recognition of Jerusalem’s status as perhaps the top irritant in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Many Middle East experts in the US who supported the embassy move as a long-delayed recognition of reality – that Jerusalem is Israel’s capital, and that recognizing it as such does not determine its final status in a peace accord – lament the impact of the way the move was carried out.

“When it comes to the Middle East we tend to exaggerate the importance of events as they are happening. We’ve seen a pattern of that every time there is violence, particularly over some US action or policy,” says Michael Rubin, a resident Middle East scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. “But I do think we should worry about how Israel is transforming into a political football in the US.”

Netanyahu's role

The hyper-partisan nature of the embassy dedication ceremony underscored a tendency set in motion by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in his “antagonism” of Democrats, Mr. Rubin says. He cites in particular Mr. Netanyahu’s willingness to take a political side in the US debate over President Obama’s signature foreign-policy accomplishment, the Iran nuclear deal.

Netanyahu’s “unabashed embrace of President Trump has greater ramifications in Congress and in the US broadly than in Israel,” Rubin says. He notes that four US senators, all Republicans, attended Monday’s ceremony. And he says it was politically pointed but “tactless” to leave the former US ambassador to Israel, Obama appointee Daniel Shapiro, off the invite list.

Indeed the politicization of US Israel policy was highlighted by the new US ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, when he told an audience at a pre-embassy dedication event Monday that the move is playing particularly well with Trump’s base.

“One of the things that gratifies me tremendously is that now we are entering yet another campaign season and as the president travels throughout the nation, his biggest applause line in places like Indiana and Michigan – I’m not talking about Long Island or Borough Park – is when he reminds people he is moving the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem,” Ambassador Friedman said. “It is the single most popular thing he has done.”

On the other hand, the political gains Trump has secured with the embassy move have been offset by the deepening divisions among American Jews over US Middle East policy, according to Mr. Halperin – and a further alienation of most American Jews from the Trump administration.

Moreover, Halperin worries that the blunt-force tactics Trump is employing in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – and Netanyahu’s full embrace of those tactics – are “fueling a growing disaffection of young American Jews” toward Israel.

That disaffection will only have been exacerbated by the “split-screen” optics of an embassy dedication ceremony taking place even as dozens of Palestinian protesters died at the hands of Israeli soldiers a few dozen miles away. “Many of us who supported the move to Jerusalem saw the timing on the eve of Nakba day as an unforced error that is going to reverberate for a long time to come,” Halperin says.

Lack of balance

Indeed, to some regional experts, the biggest impact will be not so much from the US embassy move itself, but from the fact that the one world power that has been able to move the peace process along by balancing steps favored by both sides gave Israel a coveted prize without even mentioning Palestinian aspirations.

“When the US takes a hugely consequential step like moving its embassy to Jerusalem without saying anything about Palestinians aspirations for the city, it effectively takes itself out of the game,” says Nathan Stock, a non-resident scholar with the Middle East Institute in Washington.

If Trump had really wanted to further his goal of a peace deal between Israelis and Palestinians, Mr. Stock says, “he would have made a statement in December supporting Palestinian aspirations for a capital in East Jerusalem at the same time he announced the embassy move. Now that would have been a bold move,” he adds, “but he didn’t do that.”

Stock, an expert in Palestinian politics, says that instead of focusing on the bloodshed in the recent Gaza buffer zone violence, more attention should be paid to the largely nonviolent and unarmed nature of the Palestinian protests.

“Rockets are not flying from Gaza into Israel,” he says, “so I think the question now is, does something constructive come out of this” largely nonviolent mobilization, he says. “If not, I’m concerned the result could be something much worse.”

Rubin of AEI says that those looking for something positive at this point in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have to hope for some resolution of the deep divides among Palestinians. “The looming issue now is Palestinian politics, that’s really what the Gaza violence is about, but we’re getting distracted” by the spectacle of the US embassy move, he says.

If the Palestinians can resolve their leadership issues and become a stronger, unified party in the conflict, it could be something an intrigued Trump could seize upon to accomplish his “ultimate deal,” Rubin says.

Noting Trump’s proclivity for surprise moves and reversing his thinking on issues, Rubin says, “I wouldn’t be surprised if Trump unilaterally designates as part of his tightly held peace plan that certain neighborhoods in Jerusalem are to be Palestine’s capital,” he says. “People may find Trump suddenly siding with the other camp.”

• Correspondent Dina Kraft contributed from Jerusalem.

Share this article

Link copied.

New push on immigration roils midterms – and House Republicans

Immigration has long been one of the most intractable issues in Congress. But our reporter sees signs of movement. Facing tough reelection battles, some moderate House Republicans are trying to force legislative action to help "Dreamers."

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Republican primaries this spring have shown how much President Trump has shaped mainstream GOP thought on immigration. For candidates campaigning in less-diverse districts, Trump-style immigration rhetoric is now often the default. But for a cohort of embattled, centrist House Republicans, there’s a different imperative: to help their constituents. That’s sparking an unusual, late-season effort to bypass GOP leadership and force votes on measures to protect some 690,000 young unauthorized immigrants who came to the United States as children and are currently shielded from deportation by the Obama-era program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. Mr. Trump ended DACA last fall, and Congress has so far failed to pass a replacement, although litigation has been keeping the program alive temporarily. Supporters say the maneuver could be key to the GOP’s effort to keep its House majority. Trying to force a vote on DACA “makes absolute political sense for members who represent ethnically diverse districts,” says former Rep. Tom Davis (R) of Virginia. But to conservatives, the move empowers Democrats and sets up potential passage of a bill that flouts Trump’s immigration priorities.

New push on immigration roils midterms – and House Republicans

Two months ago, after passing an enormous spending bill to fund the government, Congress seemed all but done for the year – ready to wrap things up in Washington and focus on winning reelection at home.

But now, the midterm election campaign – and the tight battle for control of the House – is sparking a late-season legislative push on immigration. An unusual effort by centrist House Republicans to force votes on measures to help the so-called “Dreamers” is putting the GOP’s congressional leadership in a bind.

To supporters of the maneuver, it represents a boost for small-d democracy – and the potential to save the GOP’s House majority. To opponents, it’s a formula for disaster, exacerbating the party’s internal rift on a hot-button issue, while advancing liberal priorities.

At center stage are the Dreamers, young unauthorized immigrants who came to the US as children. Some 690,000 of them are currently protected from deportation by the Obama-era program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. President Trump ended DACA last September, and gave Congress six months to pass a replacement. Congress failed, although litigation has been keeping the program alive temporarily.

Now, some House GOP moderates facing tough reelection races are urging another attempt at a fix. As they and their supporters note, helping Dreamers is popular with the public.

“A large majority of Americans support DACA, and there has to be a solution,” says Republican strategist Rick Tyler, a former adviser to ex-House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Sen. Ted Cruz (R) of Texas.

It also could be key to the GOP’s effort to keep the House majority. The rare maneuver to bypass leadership and bring legislation directly to the House floor is being deployed by some of the most endangered lawmakers in this election cycle: moderate Republicans.

Trying to force a vote to protect Dreamers “makes absolute political sense for members who represent ethnically diverse districts,” says former Rep. Tom Davis (R) of Virginia. “Basically, you say, ‘Well, leadership, I like you, but I’ve got to survive, and I’m not going to survive if I go with your playbook.’ ”

Mr. Trump has expressed sympathy for Dreamers, but he has also insisted on twinning permanent legal status for them with other, tough immigration measures: full funding for the US-Mexico border wall, ending the visa lottery, and curtailing family sponsorship for visas. Cracking down on illegal immigration was a core Trump campaign promise, one that strongly resonates with his base supporters, who still chant “build that wall!” at his rallies.

The president’s intense feelings on immigration came out last week when he reportedly berated Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen at a Cabinet meeting, saying she had failed to secure the nation’s borders. Secretary Nielsen was said to have considered resigning in response.

To Trump critics, the president’s posture on immigration reflects a nationalist worldview that appeals to his base on a deeply cultural level, and is key to energizing them for the midterms. GOP primaries this spring have reflected how much Trump has shaped mainstream Republican thought on immigration. For candidates campaigning in less-diverse districts, Trump-style rhetoric is now often the default.

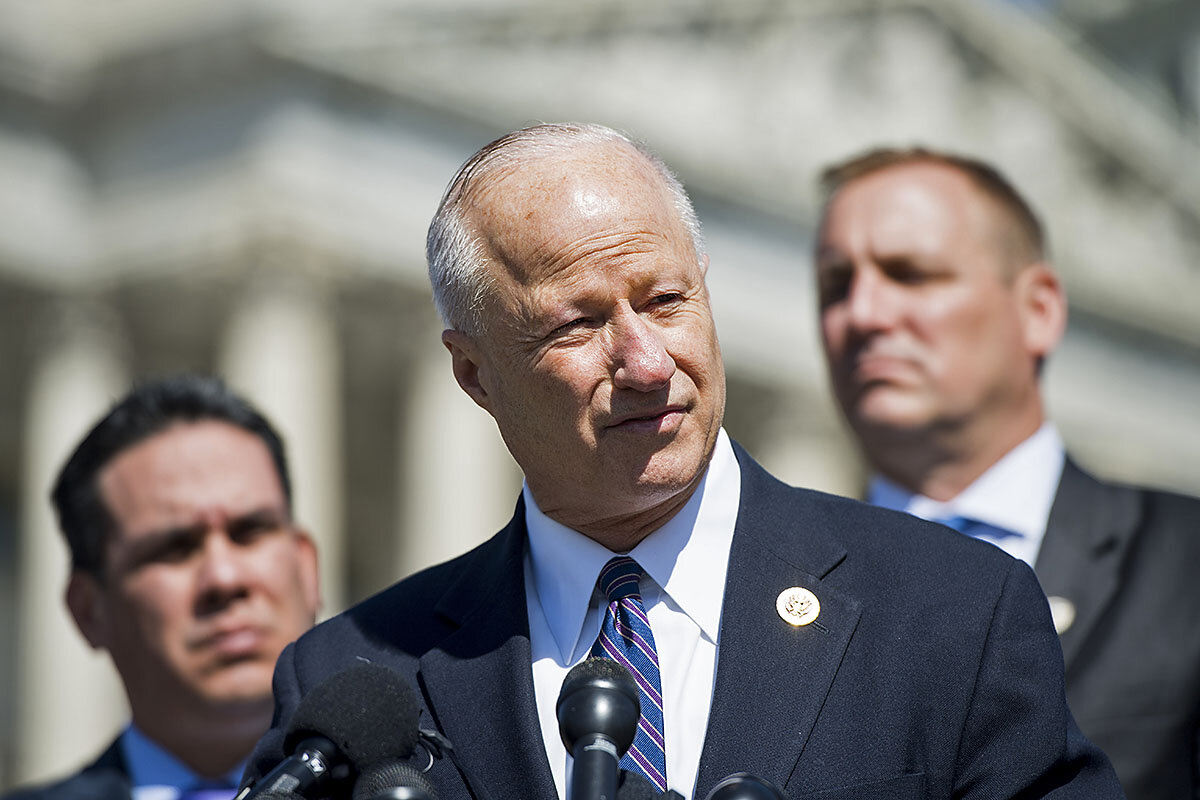

But to a cohort of embattled, centrist House Republicans – including Reps. Carlos Curbelo of Florida, John Faso of New York, Jeff Denham of California, and Mike Coffman of Colorado – there’s a different imperative. To survive reelection, they believe they need to be seen distancing themselves from Trump and trying to help their constituents, including DACA recipients and people sympathetic to them, even if they don’t ultimately succeed in passing actual legislation.

Thus was born the initiative, led by Congressman Curbelo, and now joined by 17 other House Republicans, to file a so-called discharge petition that would bring four pieces of immigration legislation to the House floor for separate votes, in an unusual procedure known as “Queen of the Hill.” The bill that gets the most votes would pass, as long as it received a majority.

House Speaker Paul Ryan opposes the petition, saying he doesn’t want votes on legislation the president won’t sign. “I don’t want show ponies,” he told reporters last week. Still, he said he wants to have a vote on immigration before the midterms.

To enact the discharge petition, a majority of the House – 218 members – would need to sign. That means Curbelo and his allies need to secure the support of 25 Republicans; the assumption is that all 193 House Democrats would sign.

The four pieces of legislation listed in the petition range from one that provides a path to citizenship for Dreamers with no tradeoffs, to a conservative bill that combines temporary status for Dreamers with deep cuts to legal immigration and stepped-up law enforcement. One of the four bills would be drafted by Speaker Ryan.

Some conservatives see this four-bill scenario as dangerous – not only because it would represent a takeover of the House floor by a faction of moderates, in concert with the entire Democratic caucus, but also because of the legislation that might result.

“This ‘Queen of the Hill’ structure gives maximum cover to immigration maximalists in Congress,” writes Fred Bauer in National Review.

Still, not all House conservatives are opposed to the move – such as Rep. Chris Collins of New York, a strong Trump ally who signed the discharge petition.

“We can’t just do nothing,” Congressman Collins told The Weekly Standard last week, adding that he’s eager to find a solution for unauthorized workers in his district near Buffalo and Rochester.

Other Republicans who have signed the petition aren’t running for reelection – including moderate Rep. Ileana Ros Lehtinen of Florida and now-former Rep. Charlie Dent of Pennsylvania – and so they face no potential consequences for participating. (Mr. Dent retired from Congress last Saturday, but his signature on the petition still counts as long as a special election isn’t held to replace him.)

Even a leader of the conservative House Freedom Caucus who opposes the petition applauded his party’s moderates for their hardball tactics. “I don’t like it, but you know, I appreciate their tactical savvy,” Rep. Jim Jordan (R) of Ohio told The Wall Street Journal.

Discharge petitions rarely work. The last time one succeeded was in 2015, when Congress revived the Export-Import Bank. But they can provide a path around gridlock, and perhaps even show Americans that the deeply unpopular Congress isn’t moribund.

“What they’ve proposed is a really open process. Everyone gets their shot,” says Neil Bradley, executive vice president and chief policy officer at the US Chamber of Commerce, which supports a path to citizenship for Dreamers. “That’s a very small-d democratic way to do it.”

Even if the end result is just a debate, Mr. Bradley says, “that still helps advance the purpose – if it gets us closer to a solution.”

Life on a volcano: Hawaiians face Kilauea eruption with reverence

Land is often associated with stability. But the residents of Hawaii have long known that their relationship with Mother Nature is dynamic. Many are responding to the latest volcanic eruption with grace, resilience, and respect.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Jason Armstrong Contributor

The ongoing eruption of the Kilauea volcano on Hawaii's Big Island has forced roughly 2,000 people to evacuate their homes since May 3. The molten rock spewing from 20 fissures on the side of the shield volcano has already destroyed more than two dozen homes. But many evacuees are not responding with anger. “Who am I going to be mad at, Mother Nature?” says Eddie Chatman, who has been living at an evacuation shelter since lava drove him from his home of 14 years. This is not an attitude unique to Hawaii. People affected by volcanism around the world often find ways to see beyond its initial destruction to the rejuvenation that follows. Once the poisonous gas, smothering ash clouds, and fiery lava subside, new earth has formed. Eventually, seeds and spores begin to take hold, sprouting new life. “What is constant,” says Karen Holmberg, an archaeologist who specializes in volcanism, “is this sense of respect for that double edge of destructiveness and creativity that an active volcano embodies.”

Life on a volcano: Hawaiians face Kilauea eruption with reverence

The scene could be described as apocalyptic. Lava and poisonous gas spew out of black gashes in the earth. Molten rock crawls through green lawns, down tree-lined streets, devouring cars, houses, and anything else in its way. The contrast between the raw volcanism and the subdivision it’s invading is unmistakable.

With 20 fissures opening up in residential neighborhoods situated on side of the shield volcano Kilauea on Hawaii's Big Island since May 3, some 2,000 people have been forced to evacuate and more than two dozen houses have already been destroyed. There is also the added threat of an explosive, steam-driven eruption from the summit.

These homes hold residents’ worldly possessions, valuables, keepsakes, and memories of children grown. Despite these losses, the default reaction has not been one of anger. Instead, in a demonstration of resilience, evacuees are responding with acceptance, and even reverence for the power of nature.

“Who am I going to be mad at, Mother Nature?” says Eddie Chatman, a self-employed landscaper who has been living at an evacuation shelter since lava drove him from his home of 14 years in Leilani Estates.

“This is part of the lifestyle for all of us,” says Henry Poe, who volunteered to stand in the driving rain last Thursday directing traffic into one of the aid centers established for the evacuees. Mr. Poe himself evacuated his neighborhood of 28 years.

Relinquishing control

Volcanic eruptions serve as a reminder of nature’s dynamism and unpredictability, says Judith Schlehe, a sociocultural anthropologist at the University of Freiburg in Germany. The natural world isn’t the controllable backdrop to human activities that it might seem.

Around the world, people who live on land which they cannot control – on volcanoes, atop fault lines, or near glaciers – have found a sense of stability and control within.

“People want to make sense of something that is beyond control, beyond understanding, beyond technological measures, and then we find all kinds of explanations,” Dr. Schlehe says.

In Hawaii, that takes the form of Pele: the goddess of fire.

“Pele is the life-force of the volcano,” explains Davianna Pōmaikaʻi McGregor, a professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of Hawai’i, Manoa, and a historian of Hawaii and the Pacific.

All of the phenomena associated with an eruption – earthquakes, explosive eruptions, slow eruptions, ash clouds, lighting, etc. – are part of Pele’s energy. “It helps us always be aware, be alert, and never take anything about this dynamic volatile force for granted,” she says. “If you choose to live there, you are always living at the grace of this force.”

A sense of respect

Volcanoes also underscore the division between human society and natural forces.

“A volcanic eruption is just a volcanic eruption unless there happens to be people in its way, and then it’s a natural disaster,” says Karen Holmberg, an archaeologist who specializes in volcanism and a visiting scholar at New York University’s Institute for Public Knowledge.

The destruction at Pompeii in particular influenced thinkers of the 17th and 18th century, Dr. Holmberg says, because the volcanically entombed city was a site along the Grand Tour, a route through different European sites toured by wealthy young men as they came of age. A relationship to nature emerged that endures in Western literature today: that nature is dangerous, and imperils culture, and therefore must be kept separate from humanity.

When a volcano erupts, it is initially a destructive force, spewing poisonous gas, smothering ash clouds, and fiery lava. But it has a rejuvenating side, too. The once-molten rock and ash form new earth. Then rain falls and weathers the volcanic rock. Eventually, seeds and spores begin to take hold on the new ground, and there is recolonization, rebirth.

Although the volcanic allegories around the world vary, many serve to integrate these two halves, showing the way toward humans living in harmony with the rest of the natural world.

“What is constant” in these legends, Holmberg says, “is this sense of respect for that double-edge of destructiveness and creativity that an active volcano embodies.”

In Indonesia, for example, some residents speak of the volcanic Mount Merapi as a friend.

“It gives them wealth and prosperity, whether it’s through mining volcanic ash or whether it’s just because of the richness of the soil,” says Gavin Sullivan, a scholar in the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University in England.

But when the volcano erupts, as happened in Indonesia on May 11, there’s a sense among the communities living around the mountain that they somehow angered the gods.

Finding meaning in destruction

Many of the legends around volcanoes involve some sort of agent behind the natural disruption of an eruption, be it a god, goddess, or some other spiritual entity. Usually that being has human-like characteristics.

With such a familiar actor associated with the eruption, “then we have an entity that we can relate to, and that gives us a kind of symbolic control back,” Schlehe says. “We can give offerings, we can ask for support, or we can find explanations for what happened.”

But it’s not just about finding meaning in one specific overwhelming event. Stories of eruptions, usually imbued with metaphor, are passed on from generation to generation so that knowledge of what happens during an eruption is not lost, Holmberg explains. As a result, eruptions are less foreign and scary for generations that haven’t experienced one themselves.

In Hawaii, for example, “Our ancestors were very keen observers and scientists, and they recorded their observations in chants that honor this volcanic energy, or Pele,” McGregor says. These chants both honor Pele and relay details of past eruptions and the natural grumblings that happen before an eruption that can help people know what’s coming.

“Volcanologists take oral traditions and indigenous stories about volcanoes pretty seriously,” says Clive Oppenheimer, a volcanologist at the University of Cambridge. “They quite often turn out to have very scientifically relevant and useful information.”

At home on the flow

Not everyone who lives on an active volcano has the same relationship to the land. Some chose to live there for various reasons, others inherited the land from generations that came before, or had little choice in the matter. And those varied connections to the land influence someone’s calculation of the risk they face, Dr. Sullivan says.

Lava may have claimed Del Pranke’s Leilani Estates home of seven years, but he doesn’t plan on leaving the area. “People have asked me if I’m gonna move away,” he said as he sat on an air mattress with his dog at the Pahoa evacuation shelter Hawaii County is running the town’s gymnasium. “That’s ridiculous. I would never think of leaving Puna.”

Besides being seismically hyperactive, this region is one of the least developed in an island chain distinguished as the most isolated land mass on Earth. People don’t stumble on the district of Puna. Regardless if they were “grown or flown” here, residents are hearty. Many forgo the pitfalls of urban life to rely on generators, dirt roads, and captured rainwater for basic needs.

Mr. Pranke is a self-described “Punatic,” a common term that can be seen on bumper stickers in the area to describe someone who loves living in Puna. And he isn’t the only person who plans to return – whether their home still stands or not.

“I plan to stay and live here. I love it here. This is my home. I don’t want to move anywhere else,” said Mr. Chatman, whose family moved to Hawaii Island from California when he was 2 years old. For the past 14 years, he’s resided in Leilani Estates, the larger of the two neighborhoods under emergency evacuation.

This sentiment isn’t exclusive to Hawaii. A study Sullivan and Indonesian colleagues conducted of people living around Mount Sinabung in Sumatra when it erupted in 2010 revealed that the people who remained in their village after the eruption had a higher self-perceived social status than those displaced, despite knowing that they were exposed to more eruptions by staying.

“I want to go back,” Leilani Estates evacuee Cecilia Ascher says. “I’m positive of going back.” She adds that people who choose to live on a volcano “have to be strong and go with the flow.”

Staff writer Eva Botkin-Kowacki contributed reporting from Boston and contributor Jason Armstrong contributed reporting from Pahoa, Hawaii Island.

[Update: This story was updated at 3:30 pm to include the latest fissure to open up on Kilauea. There are now 20 open fissures.]

In Nigeria, an ethical struggle at the heart of a medical strike

Health-care workers are by definition service oriented. So, a hospital strike – withholding care – presents inherent ethical challenges for them. But in Nigeria, the situation is in desperate need of improvement.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A strike by public hospital workers in Nigeria is entering its fourth week, with only doctors showing up and care sharply curtailed. It symbolizes a health-care system that, despite Nigeria’s status as Africa’s largest economy, lags far behind global standards. A 2017 study ranked Nigeria 140th of 195 countries in health-care quality. Patients and staff at public hospitals complain of the low standard of care, with institutions often missing equipment like X-ray machines as well as more basic supplies such as gloves and gauze. Adding to the dissonance is the prevalence of “medical tourism” trips by elites including President Muhammadu Buhari, who was London-bound for treatment last week. The situation is ethically fraught: The strike erodes care for now, but the goal is to improve wages and morale for workers who say pay is inequitably divided between doctors and other hospital workers. “I support this strike now,” says Emmanuel Uwazuruike, a taxi driver who’s had bitter experience with the hospital system in Abuja. But he adds, “When they strike, it is ultimately the poor who will suffer.”

In Nigeria, an ethical struggle at the heart of a medical strike

When the presidential jet roared down the runway at the international airport in Nigeria’s capital last week, it was leaving on a familiar mission. The country’s president, Muhammadu Buhari, was bound for London, where he regularly travels for medical treatment.

Since taking office in 2015, in fact, Mr. Buhari, who is 75, has spent about six months in Britain for visits with his doctors. His so-called “medical tourism” has drawn sharp criticism from many at home, who have often asked why he doesn’t have enough faith in his own country’s hospitals to use them himself.

But this time, the contrast between the president’s care and that of ordinary Nigerians was particularly stark. As Buhari’s plane whisked him away, it passed over a country of ghost hospitals. A strike of nurses, pharmacists, and other workers over wages and working conditions at federal public hospitals was dragging into its fourth week. Doctors were the only staff on duty, and most institutions were turning away all but the most urgent cases.

The dissonance has drawn renewed attention to the longstanding crisis of care in Nigeria’s creaking public hospitals. The country has just one doctor for every 5,500 people, well below the World Health Organization’s standard of 1 every 600.

But the strike has also raised questions of just how far a strike can go in fixing the problems that ail the health system of Africa's largest economy – and who, exactly, stands to gain and lose when health workers walk off the job.

Medical strikes “are a fraught ethical issue,” says Ike Anya, a Nigerian public health expert and the co-founder of the popular blog Nigeria Health Watch. And that’s particularly true in a country like Nigeria, where those who use public hospitals often have no other options for medical care.

“But there are other ways to see it as well – for instance, poor staff morale also does nothing to help your health outcomes in the long term,” Mr. Anya says.

Nigeria’s health outcomes, by all accounts, demand improvement. In a 2017 study of global health care quality, Nigeria ranked 140th of 195 countries. Both patients and staff at public hospitals complain of the low standard of care, with institutions often missing equipment like x-ray machines as well as more mundane supplies like gloves, needles, and gauze.

And when workers in those circumstances feel no one in power is addressing those issues, “a strike often becomes the only way to get government to pay attention,” Anya says.

Turning people away

For Margaret Obono, who heads the pharmacy department at the National Orthopedic Hospital in Lagos, striking would never have been her first choice. But it was a response, she says, to the overwhelming frustrations of working in a hospital where she regularly had to turn patients away because she didn’t have the medicines they needed.

“No pharmacist wants to be the one to tell a patient treatment is not available [because of money],” she says.

Strikes have repeatedly roiled Nigerian hospitals over the past decade, mostly concerning pay, which many health workers say remains unconscionably low and inequitably divided between doctors and other hospital workers. Nurses and pharmacists generally earn about $400 a month, and unions say government has repeatedly backpedaled on agreements to raise wages.

“We have been waiting years for a salary adjustment that has never come,” says Biobelemoye Joy Josiah, chairman of the Joint Health Sector Union, which called the strike.

For its part, the government says it knows the health care sector is “troubled,” but says workers must be more patient. (Negotiations between the two sides are continuing this week in hopes of ending the strike.)

Shortages and bribes

To many Nigerians, meanwhile, the rot goes far deeper than anything a workers’ strike could solve.

Emmanuel Uwazuruike describes walking into a public hospital in Abuja in 2013 with his wife, who had just gone into labor. Before she had even been given a bed, the nurses on duty handed Mr. Uwazuruike a list – towels, gauze, sanitary pads, gloves. It was all the supplies he would need to provide for his wife’s delivery.

“But when I came back from buying everything, the nurses told me I must also give them some money, too, or they won’t deliver the baby,” says Uwazuruike, who works as a taxi driver. He handed over another precious fistful of Naira notes, and then the nurses disappeared, he says. Hours passed, he says, and his wife grew weak and listless. Finally, the doctor informed them that she needed an emergency C-section, and wheeled her off.

A harrowing hour later, a nurse burst into the waiting room. He had a son, she said, a healthy baby boy. His wife was dead.

He never found out the details, he says, but he suspected that if the family had access to a better hospital or more attentive health care workers, it might not have happened.

“So I support this strike now, but I am also frustrated by our doctors and nurses, too,” he says. “And when they strike, it is ultimately the poor who will suffer.”

An unfulfilled promise

Like many Nigerians, he also watched in anger as, in the midst of the strike, Buhari once again left for England. During his presidential campaign in 2015, Buhari had promised to end the elite’s infamous “medical tourism” to richer countries.

“We will certainly not encourage expending Nigerian hard-earned resources on any government official seeking medical care abroad, when such can be handled in Nigeria,” Mr. Adewole, the health minister, said in 2016, speaking on behalf of the president at a conference.

“Most countries’ presidents use their own health care systems – it’s an embarrassment that ours doesn’t,” said Nelson, a cybersecurity analyst in Abuja, as he jiggled his young daughter on his hip outside the doors to a public hospital on a recent afternoon. (He gave only his first name over concerns about his family’s privacy).

Meanwhile, across town, the grounds of Abuja’s National Hospital, normally crowded with a cacophony of patients, visitors, and informal hawkers, were nearly empty. Inside the emergency ward, two young doctors played games on their smartphones, the only noise the hum and thwack of an air conditioner in the background.

The hospital was open, but without nurses, pharmacists, or other support staff, it could see only a few cases a day.

“Normally in a shift you’d see maybe 50 patients,” says Emmanuel Okeke, a junior doctor here. “Now we are seeing maybe five, so we worry – we wonder where the rest are going, if they’re going anywhere at all.”

For women in law, 'RBG' is their superhero movie

For many women, especially women judges and lawyers, US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is more than just a role model. She's "Notorious RBG." But the emergence of justices as pop political icons, some say, could weaken the judicial system.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In a youth-driven culture, an opera-loving octogenarian celebrity who favors lace gloves and something called a jabot is a singularity. But in San Antonio, Friday’s screening of the documentary “RBG” completely sold out. The new documentary about Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a Top 10 film, along with “Avengers: Infinity War.” “She is an icon, and an icon to us all as women,” said Salena Santibanez, who attended the screening organized by appeals court Justice Rebecca Martinez. There are those who wince, however, at the “Notorious R.B.G.” persona with its coffee mugs and snarky T-shirts, and who feel uncomfortable with the cult of personality – and its undeniable partisan roots – of someone who is supposed to represent the least political branch of government. Others point out that Justice Ginsburg is hardly the first justice to be hero-worshiped; she's just the first woman to achieve that status. “You can have a hero, but blindly worshiping that hero from any point on the political spectrum is never advisable,” says Bridget Crawford, a professor at Pace Law School in White Plains, N.Y. “That means you’ve yielded your critical reasoning to someone else’s cult of personality, and that’s not positive in a democracy.”

For women in law, 'RBG' is their superhero movie

A long line at a movie theater on a Friday night tends be a sign of the latest superhero movie. The people lining up at the Santikos Bijou theater in San Antonio Friday night may not have entirely disagreed.

Several of them were dressed in costumes, after all. But instead of a mask, cape, or Hulk Hands, they were wearing paper gold crowns and black judge’s robes with jabots.

They were lining up for a special sold-out screening of “RBG,” a documentary by Betsy West and Julie Cohen about Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“Everyone loves a hero story,” says Justice Rebecca Martinez, who serves on the Texas Fourth Court of Appeals here and organized the screening. Some 30 percent of the tickets went to high school students, so they could see the documentary for free.

“We have the rights we have now because of the strides she made under her jurisprudence,” adds Justice Martinez, speaking before the screening wearing a black robe and a gold jabot.

The crowd that night constitutes a fraction of the millions of admirers Ginsburg has attracted in recent years. Her impassioned dissents, and an increased awareness of her early work as a lawyer fighting gender discrimination, have transformed her from sober Supreme Court justice to a celebrity, cultural icon, and meme. To a younger generation of court watchers in particular, she is not just the second female justice in the high court’s history, but also “the Notorious RBG,” a fire-spitting (from the bench) progressive warrior playfully equated to the 1990s gangster rapper Notorious B.I.G. (Both are Brooklyn natives, as Ginsburg has pointed out.)

There are those who wince, however, at the coffee mugs, key rings, and snarky T-shirts, and who feel uncomfortable with the hero-worship and cult of personality – and its undeniable partisan roots – of someone who is supposed to represent the least political branch of government. Even some legal experts who are enjoying her relatively newfound cult of celebrity acknowledge that, in terms of progressive bona fides, the myth of “the Notorious RBG” doesn’t quite match up to the reality of Ginsburg herself.

She is by no means the first justice to achieve celebrity status. Justice Antonin Scalia, her right-wing foil and good friend on the high court, enjoyed a similar popularity among conservatives before his death in 2016. (Scalia bobbleheads were highly coveted – and hard to come by.) But they both represent “the emergence of justices as symbolic political figures, and indeed ideological figures,” says David Garrow, an expert in Supreme Court history and author of “Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe v. Wade.”

“With both of them, it has such an explicitly ideological, explicitly partisan emphasis to it,” he adds. “I think to have purposely partisan-identified justices does huge damage to the court.”

Indeed, until the 1980s it was rare for justices to speak in public, and it was even rarer for anyone to pay attention to them when they did. Justice Hugo Black gave an interview on CBS in 1968, for example, but because he was broadcast opposite a program with movie star Brigitte Bardot “it went largely unnoticed by the general public.” The “RBG” documentary, meanwhile, cracked the top 10 in the box office over the weekend after opening in just 180 theaters.

The documentary plays on her celebrity persona, with “The Bullpen” by rapper Dessa playing over shots of Ginsburg working out, before diving into the life of the retiring woman who was one of only nine women in the class of 1959 at Harvard Law School. Ginsburg made law review her second year, while caring for a baby daughter and her husband, who had been diagnosed with cancer. She transferred to Columbia when he became a tax attorney in New York. Marty Ginsburg later returned the favor, cooking dinner for the kids every night and leaving his job to follow Ruth to D.C. when she was appointed to the federal bench.

Finding her voice in dissent

The “Notorious RBG” persona does have explicitly partisan roots, roots that only took hold after she had already spent 12 years on the Supreme Court.

After a trailblazing legal career in which she co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union’s Women’s Rights Project and argued for gender equality as a lawyer – winning five of the six cases she argued before the Supreme Court – Ginsburg surprised some observers when she remained a quiet presence on the high court in her first years there.

It wasn’t until around the mid-2000s – after Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the court’s first female justice, retired – that she became more outspoken. Her dissent in the Lily Ledbetter fair pay case in 2007 is marked by Linda Greenhouse of The New York Times as the moment Ginsburg “found her voice, and used it.”

It was her dissent in the 2013 Hobby Lobby case – in which the court ruled, 5-to-4, that private companies can refuse on religious grounds to provide contraceptive care to their employees – that cemented her status as a youth icon.

That dissent, Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick wrote in 2015, “became a cri de coeur popularized in viral Facebook memes and a tribute song. Notorious R.B.G., crown and all, became the face of female employees in Hobby Lobby, and female workers everywhere whose bosses’ religious preferences might trump their right to birth control.”

Ginsburg is enjoying her popularity, by several accounts. (She has “quite a large supply” of Notorious RBG t-shirts, she told NPR’s Nina Totenberg, and she hands them out to friends.) But while Ginsburg may be the most well-known and popular Supreme Court justice, at least on the left, in reality she is – at least on some issues – one of the court’s more moderate voices.

“She’s publicly aligned as the most liberal [justice], but any law review article will show you she’s much more moderate,” says Tracy Thomas, a professor at the University of Akron School of Law who criticized Ginsburg last year for her opinion in a case ruling that until Congress legislates otherwise, the foreign-born child of an unwed American mother or father can be eligible for US citizenship only if the parent had five years of physical presence in the US, striking down an exception that had required unwed mothers to only have one year of physical presence. (The decision stripped the plaintiff of his citizenship.)

“I think some of her reverence for [due] process and deference to the Congress is kind of naive politically,” adds Professor Thomas. “She can write a nice opinion on equality, but if nothing happens for the litigants, it’s the opposite of what she used to do” as a lawyer.

An irony of the “Notorious RBG” phenomenon, experts note, is that Ginsburg has always embodied a more old-school activism – a commitment to litigating instead of protesting. “Marching and demonstrating wasn’t Ruth’s thing,” her biographer, Wendy W. Williams, points out in the documentary. Ginsburg instead favored incremental change through litigation, which was how the civil rights movement achieved some of its great successes. She’s repeatedly described as reserved and quiet in the film, and cites her mother’s advice to act like a lady.

Criticism for public remarks

As her celebrity has grown, she has also been criticized for some of her public comments. Two years ago, some of her supporters were surprised when she dismissed NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s protests against police brutality as “dumb”. She later apologized.

Not long after, she told The New York Times: “I can’t imagine what the country would be with Donald Trump as our president.” Days later she doubled down, calling candidate Mr. Trump “a faker” with “an ego” and “no consistency about him.” The comments led to Mr. Trump calling for her to resign, and others to call for her to recuse herself from Supreme Court cases involving President Trump. Ginsburg apologized the same week, calling her remarks “ill-advised.”

But not only has she not recused herself from Trump-related cases – including the travel ban case the court heard this term – but she skipped his first State of the Union address, an event every justice traditionally attends. She instead spoke at Roger Williams University School of Law in Rhode Island, discussing her fears that the federal judiciary could start to be seen as another political branch of government.

Cult of judicial worship

Given how outspoken and sometimes flamboyant past justices like Justice Scalia and Chief Justice William Rehnquist – who designed black robes with four gold stripes on each sleeve, a nod to Gilbert and Sullivan, for presiding over the Clinton impeachment hearings – have been, some see the critique of Ginsburg’s conduct as a gendered one.

“The cult of judicial worship is not limited to Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” says Bridget Crawford, a professor at Pace Law School in White Plains, N.Y., and a curator of the Feminist Law Professors Blog. “It’s getting the most attention because she’s a woman, and we’ve taken for granted in the past the hero worship that’s been done with men.”

“Why has it developed? Because the left is looking for heroes, and there are so few who merit that status,” she adds.

At the San Antonio documentary screening, Salena Santibanez echoed this sentiment.

“She is an icon, and an icon to us all as women,” she said, adding that she likes Ginsburg’s “tenacity, and her ganas,” a Spanish word for “giving 100 percent.”

Professors Crawford and Thomas both enjoy the attention Ginsburg is receiving. Crawford has a Ginsburg pennant in her office, while Thomas “loves” that Ginsburg is “the only justice” her high school-age daughter knows. But they also believe she shouldn’t be immune from criticism.

“You can have a hero, but blindly worshiping that hero from any point on the political spectrum is never advisable,” Crawford says. “That means you’ve yielded your critical reasoning to someone else’s cult of personality, and that’s not positive in a democracy.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The peace in learning to discern the news

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For all the advice given to news consumers, how much do they end up becoming earnest truth seekers – and how long do the lessons last? Perhaps the best lab to test such training is Ukraine. Since 2014, when a popular revolution overthrew a pro-Kremlin regime, Russia has conducted a disinformation campaign in its neighboring state, probably to sow division and steer Ukraine from joining Western organizations or becoming a showcase for democracy. A pushback: In a 2015-16 experiment called Learn to Discern, more than 15,000 Ukrainians participated in workshops that trained them to “better identify fake news stories and actively seek out high-quality news and information.” The results, just released, are encouraging: Participants were 13 percent better than their peers at identifying and analyzing fake news stories – even 1-1/2 years after completing the program. And 25 percent were more likely to check multiple sources. Those who took the course were eager to share their new skills with others. News discernment, a Swedish researcher once wrote, is “understanding as a source of mental peace.” With good training in media literacy, perhaps more people can gain that peace.

The peace in learning to discern the news

If you’re reading this with a critical eye, welcome to the crowd. In recent years, more American high schools have begun to teach “media literacy,” especially during an era of “fake news.” More news outlets now offer truth checks on public statements. And as the United States heads into an election, voters will be reminded of how Russia manipulated social media in an attempt to influence the 2016 presidential election.

Yet for all the training and advice given to news consumers, how much do they really end up becoming earnest truth-seekers?

One 2003 study of an 11th-grade class on media literacy found students were better able to recognize “the complex blurring” of information and entertainment in nonfiction media. But there was a problem. The effects of the training wore off after a year. Media literacy is still a work in progress.

Perhaps the best lab to test such training is Ukraine, which has long been a target of fake news and is on the front line of the information wars.

Since 2014, when a popular revolution overthrew a pro-Kremlin regime, Russia has conducted a massive disinformation campaign in its neighboring state, probably to sow division and steer Ukraine from joining Western organizations or becoming a showcase for democracy.

Many journalists in Ukraine have tried to counter the falsehoods. But that may not be working. Only 1 in 4 Ukrainians trusts the media. The alternative is to train Ukrainians to become long-term discerners of media accuracy and manipulation.

In an experiment funded by Canada, more than 15,000 Ukrainians participated in workshops in 2015-16 that trained them to “better identify fake news stories and actively seek out high-quality news and information.” The course was particularly focused on recognizing deliberate efforts to manipulate people’s emotions through misleading content. To measure the impact of the training, researchers from the nonprofit IREX used a control group. And they relied on trainers embedded in their local organizations or community.

The results, released May 15, are encouraging.

Participants in the training program, called Learn to Discern, were 13 percent better than peers at identifying and analyzing fake news stories – even 1-1/2 years after completing the program. In addition, 25 percent were more likely to check multiple sources.

Participants rated themselves as more proficient in three ways:

- When I am misinformed by the news media, I can do something about it.

- If I pay attention to multiple sources of information, I can avoid being misinformed.

- If I take the right actions, I can stay informed.

The course was so successful that IREX is now piloting the approach in Arizona and New Jersey.

One result really stood out. Those who took the course were eager to share their new skills with others. Researchers estimate that more than 90,000 people indirectly benefited.

This finding fits with what the late Swedish researcher Hans Rosling calls “factfulness,” or the practice of perceiving what qualifies as news over the course of time. News discernment, he once wrote, is “understanding as a source of mental peace.”

With the right training in media literacy, perhaps more people can gain that peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The Jerusalem we can all call home

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

At a time when the concept of “home” is too often fraught with conflict, as in Jerusalem today, today’s contributor reflects on the idea of a deeper sense of home we each share with all humanity.

The Jerusalem we can all call home

Coming home to a place of safety, comfort, and belonging is one of life’s most precious feelings, a feeling that’s universally recognized and valued. But what if one person’s sense of home seems to clash with another’s?

I was thinking about that while listening to the glorious words of a song performed a cappella by a group of Jewish men filmed singing on a hilltop in Israel:

“We’ve come home

We’ve come home

To a land of our own

After 2000 years, we are home.”

(Kippalive, “We are home”)

It’s hard not to feel a resonance with these simple words if, like me, you have Jewish parents who described not having a “home” called Israel to flee to when faced with the approaching Holocaust in pre-World War II Berlin.

But then I try to mentally put myself in the shoes of Palestinians in Jordan, Gaza, and the West Bank listening to the same song. How would the words resonate with them? Clearly, the Jewish people aren’t the only ones with a heartfelt sense of attachment to the Holy Land, especially when it comes to Jerusalem. Christian and Muslim Arabs have lived there for generations. And, as a Jewish scholar recently put it, Jerusalem is also “a spiritual home for Christians and Muslims worldwide” (Professor Paul Mendes-Flohr, “Jerusalem,” Dec. 14, 2017, divinity.uchicago.edu/sightings/jerusalem).

Over the years, I’ve found prayer to be a helpful, healing approach during times of tribulation. So I’ve been praying about this sense of conflict surrounding that most precious of things – home – too. There’s a sense of home my heart deeply desires for all to know and experience. It’s a purely spiritual sense, that has no physical location associated with it.

I believe this is the kind of home referred to in the Glossary of “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” in which Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy, the author of this book, offers a spiritual interpretation of Bible terms. Included there is a spiritual sense of the word “Jerusalem,” which simply says, in part, “Home, heaven” (p. 589).

In writing Science and Health, Mrs. Eddy intended its timeless message to speak to all humanity. So it seems to me that this spiritual sense of Jerusalem is the most profound and tangible experience of feeling “at home” available to any of us: a concrete awareness of unconditional peace and well-being, stemming from our true nature as the cherished, spiritual offspring of divine Love. Each of us can experience this spiritual sense of being at home in eternal Love as we, through prayer, come to realize and feel what it means to be wrapped in God’s care.

When we experience such uplifted thought, it feels like a homecoming – much like in a story I love in the Bible. Christ Jesus tells of a prodigal son who asked his father for his inheritance, which he then wasted (see Luke 15:11-32). Destitute, he humbly returned home, where he was met by his father, who ran to embrace him despite the mistakes he’d made.

Such spiritual homecomings aren’t a one-time event. Fresh prodigal moments await us whenever our hearts have invested their hope for happiness or health on a material basis, only to find that the well of hope has run dry, still unrealized. Then we humbly seek, and gratefully yield to, God, divine Spirit. Such spiritual stirrings may not be the return to a physical place we’ve dreamed of. But each time we glimpse more of our eternal nature as a child of God, we feel the warm glow of coming home to where we truly, spiritually belong.

Seeing the political, often violent, tumult that continues to occur in the Middle East, it’s tempting to echo a sense of lament. But God’s healing message of love is always coming to all of us (regardless of who we are), urging us to come home to the recognition of our shared dwelling place – in universal, spiritual unity.

Adapted from an editorial in the March 12, 2018, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Bridge to ... an annex?

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a global report about security and trust in an era of dramatic unilateral moves by the United States.