- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Finding strength through partnerships

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Welcome to your Monitor Daily. Today we’ll explore perceptions of racism, negotiations for peace, the identity of a protest generation, a growing embrace of women’s leadership, and defiance of societal expectations.

But first: It’s hard to get to know a place from afar. Before packing my bags for a reporting exchange in Hawaii, I did my best to learn about the 50th state. I quickly realized that my frame of reference had been built on a Hollywood fantasy.

Journalists by nature seek to probe beneath this kind of veneer. But any reporter heading into an unseen destination runs the risk of tapping into well-worn tropes.

At the Monitor, this is something we actively guard against.

My trip to Hawaii was the start of a new Monitor initiative designed to bolster those guards. During my three-week stay I was welcomed into the newsroom of Honolulu Civil Beat, a local, investigative journalism outlet. They offered me a desk, a reporting partner, and a trove of local knowledge. The editor even welcomed me into her home for the duration of my stay.

That immersion into daily life yielded a rare glimpse beyond the tropical awe of a tourist and the hyperfocus of a journalist on a brief reporting trip.

One story from that trip has already been published. Two more are still in production.

In the coming months and years, we hope to forge more partnerships like this with local newsrooms. We believe these collaborations can make us stronger, both as journalists and as citizens.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Who is a racist? Across the US, definitions vary.

If one word has dominated the U.S. news cycle lately, it’s probably “racist.” But the shouting match over presidential tweets is surfacing a divide over the definition of that incendiary word.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Dee Bragg does not think President Donald Trump is racist. Waiting in a sweltering parking lot before the president’s rally in Greenville, North Carolina, on Wednesday, the proud Trump supporter notes that his tweet telling four Democratic congresswomen of color to “go back” to the “places from which they came” never mentioned race.

“Racism is when you believe one race is better than another, and that’s not what he said at all,” she says.

Massachusetts voter William Watkins disagrees. “He’s saying to his base, it’s them. They’re the problem,” says Mr. Watkins, who is represented in Congress by Ayanna Pressley, one of the lawmakers targeted by Mr. Trump’s tweets.

There are two very different working definitions of racism in the U.S. – the red state definition and the blue state definition. Minorities and Democrats living in blue states have a broader and more comprehensive view of what constitutes racist behavior than many Republicans living in red states perhaps understand or accept. The 2020 campaign could produce an uncomfortable national reckoning with this disparity.

“People bring their own meaning to ... the word,” says Jennifer Mercieca, a historian of American political discourse. “Racism is difficult to pin down.”

Who is a racist? Across the US, definitions vary.

Hours before President Donald Trump held a rally in Greenville, North Carolina, on Wednesday night, nobody waiting in the heat and anticipation of the parking lot outside an East Carolina University auditorium said he was a racist. Nobody asked by a reporter thought his tweet telling four female members of Congress to “go back” to the “places from which they came” was racist at all.

The tweet was vague and didn’t refer directly to race, many said. Besides, “racist” is thrown around too much, in their view. Democrats use it at the drop of a MAGA hat.

“They use that word for everything now,” said rally attendee Johnny Liles of Emerald Isle, North Carolina.

Voters in Massachusetts’ 7th Congressional District had a very different view.

The 7th is represented by Ayanna Pressley, one of the congresswomen Mr. Trump referred to, and almost all of her constituents interviewed thought the tweet was racist – self-evidently so.

Many asked how anybody could doubt that “they” referred to black and brown people. The “go back” trope, long used against non-whites in America, was all the more offensive because all the women were citizens, and three were born in the U.S.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission – a federal agency – uses “go back to where you came from” as an example of an ethnic slur, said Haris Hardaway, the owner of a boutique in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston.

During the Jim Crow era, those words were “used to invalidate our humanity and our citizenship of this country,” Mr. Hardaway said. ”And that’s why I see them as racist.”

As this comparison shows, there are two very different working definitions of racism in the U.S. – the red state definition, and the blue state definition.

It’s no longer the 1960s. Most Americans would likely agree that it is racist to stand in a schoolhouse door, as then-Gov. George Wallace of Alabama did in 1963, to try to forcibly prevent the integration of the University of Alabama.

But minorities and Democrats living in blue states today have a broader and more comprehensive view of what constitutes racist behavior than many Republicans living in red states perhaps understand or accept. The 2020 campaign could produce an uncomfortable national reckoning with this disparity – particularly if Trump rallies continue to feature chants of “Send her back!” as the crowd roared in Greenville Wednesday night. For his part, Mr. Trump disavowed the chant Thursday, saying, “I disagree with it.”

“Go back to the civil rights marches in the ’50s and ’60s, and a lot of white communities did not quite understand what racism was. So this is not new. It is more modern day racism with a suit and tie,” says retiree Danny Hardaway, Haris’s father.

“Go back”: a long-used phrase

Mr. Trump’s “go back” tweet and his subsequent comments were aimed at Democratic Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts, and Ilhan Omar of Minnesota. All are women of color; all except Representative Omar were born in the U.S. (She is a naturalized citizen who came to America as a Somali refugee.)

The “go back” phrase’s long use to portray foreigners and non-white ethnic groups as not deserving of a place in America forced the news media to grapple with its descriptive terms in the wake of Mr. Trump’s eruption. Many flatly called it “racist.” Others attributed that designation to others, or used “racially tinged” or other euphemistic phrases.

Still others thought that description went too far. Fox News senior analyst Brit Hume thought Mr. Trump’s statements were nativist, ignorant, bad, and bad politics – but not racist. It didn’t meet the first definition of “racism” in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, he said: “a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race.”

Many Trump rally attendees offered variations of this position in explaining why they didn’t think his tweet was racist. It wasn’t really derogatory, they said. It did not refer to blacks or Muslims or Hispanics directly, and did not even refer to the targets by name.

“Racism is when you believe one race is better than another, and that’s not what he said at all,” said Dee Bragg, from Nags Head, North Carolina.

Others bring a different experience and heritage to the same words, and thus hear something different.

“People bring their own meaning to what the word is. ‘Racism’ is difficult to pin down,” said Jennifer Mercieca, a historian of U.S. political discourse with a forthcoming book on President Trump’s rhetoric.

Dr. Mercieca, for instance, disagrees with Mr. Hume, and believes that Mr. Trump’s statement does meet the standard definition of racism. Given the history of the phrase, what else would it be referring to, other than a minority whose position in America is thought tenuous? Without using specifics, it calls into question their place in the nation. Would anyone think to insult a white person by telling them to “go back to where you came from?”

The South enacted poll taxes, voter registration tests, and other pre-Civil Rights era restrictions on black voting rights without mentioning “black” in the laws. Were those racist?

“He’s saying to his base it’s them. They’re the problem. How could they tell us what to do? How could they come to our country and tell us what to do? But all ... these women are Americans,” says William Watkins, a 7th district voter and director of workforce development at the Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts.

Polling shows a sharp divide

A USA Today-Ipsos poll released Wednesday found that 65% of Americans aware of Mr. Trump’s “go back” statement agreed that it was racist.

But as is often the case in American politics today, that opinion broke sharply along partisan lines, with many Republicans saying it was not racist. And fully 70% of GOP respondents to the survey agreed with the statement “people who call others ‘racist’ usually do so in bad faith.”

That was another primary argument used by Trump supporters as to why they did not believe racism described his actions. Democrats and others don’t really mean it when they cry “racist,” they said. It’s just an all-purpose insult, an evocative one, used by his enemies.

“They are just so flippant with it,” said Al Byrum of Nags Head outside the President Trump rally venue.

The more it’s used, the more it loses its meaning, some Republicans say. Fox News talk show host Greg Gutfeld on Tuesday mocked CNN and MSNBC for a report that they used the word “racist” or variations 1,100 times in two days following President Trump’s tweet. National Review senior editor Jay Nordlinger – no fan of Mr. Trump or the “go back” language – himself tweeted that as a Reagan conservative he’d been called a racist so often the charge now rings hollow.

“Good job, wolf-criers,” he tweeted.

Those who feel the sting of being called racist experience it as an insult. If it’s used over and over, the power of that sting may lessen.

But those who use it see “racist” as both insult and description. It’s like calling something “blue,” to many Democrats and minorities. If you call 1,100 things blue, the 1,101st object is still blue. It hasn’t turned green due to “blue” overuse.

But the identification of something as racist can be more subjective than simply noting its color. For instance, was Nike right to recently pull from the market sneakers depicting the 13-star banner known as the Betsy Ross flag, after former football star Colin Kaepernick objected that the flag dates to the era of 18th -century slavery and has occasionally been flown by far-right groups?

That move received plenty of pushback from Republicans and some Democrats as well.

“In liberalism it’s like everything’s about racism and it’s driving me crazy,” said Denis Rouleau, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, resident and supporter of President Trump. “If you don’t agree with liberals you’re a racist. That’s how it seems to me.”

This story was reported by Story Hinckley in Greenville, North Carolina, and Noah Robertson in Somerville, Massachusetts, and Boston. It was written by Peter Grier.

The ball is in Europe’s court to save Iran nuclear deal

When tensions threaten to boil over between two rivals, sometimes the party best positioned to cool things off is the one stuck between them. In the current standoff between Iran and the U.S., that’s Europe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dominique Soguel Correspondent

If it comes to salvaging the Iran nuclear deal, it may be up to Europe to make it happen. Amid high tensions between Tehran and Washington, some experts say that it is the European signatories to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that have the best chance to convince Iran to rein in its nuclear activities.

Iran wants Europe and the remaining parties in the JCPOA to do more to offset U.S. sanctions. Last week, the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog confirmed that Iran had exceeded its uranium enrichment cap of 3.67%. But the fact that Iran is phasing its steps out of compliance has raised hopes that Tehran could be persuaded to reverse course if Europe takes small but meaningful steps.

The most tangible and visible step that Europe has taken to date is the establishment of Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges, a complex bartering mechanism to facilitate humanitarian trade between Iran and Europe. “From a European perspective, this is unparalleled,” says Iran specialist Dina Esfandiary. “They’ve never had to set up this kind of mechanism before. They’ve never had to stand up to U.S. sanctions before.”

The ball is in Europe’s court to save Iran nuclear deal

While Tehran and Washington engage in a high-stakes game of brinkmanship in the Persian Gulf, the future of the Iran nuclear deal may end up being determined not by either of those parties, but by Europe.

In May, a year after the United States pulled out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Tehran warned it would gradually decrease compliance with the deal. The posture shift was a reaction to what Iran perceives as the failure among the remaining parties – namely France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (the so-called E-3) along with Russia and China – to honor their economic commitments under the deal.

The fact that Iran is phasing its steps out of compliance – setting 60-day deadlines for each successive move such as going to higher enrichment levels – has raised hopes that Tehran could be persuaded to reverse course if Europe takes small but meaningful steps. So now European officials are desperate to keep the deal alive.

“What the Iranians want at this stage is really for the Europeans to put their neck on the line and stand up to the U.S.,” says Dina Esfandiary, an Iran specialist serving as a fellow at the Harvard Belfer Center and the Century Foundation. “If the Iranians are able to witness the Europeans doing something like that, I think that’ll go a long way towards at least making Tehran more amenable to more discussions with Europe on how to freeze the escalation that’s going on at the moment.”

Spurring Europe to act

Iran, analysts concur, has given up on strategic patience. It wants Europe and the remaining parties in the JCPOA to do more to offset U.S. sanctions. Last week, the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog confirmed that Iran had exceeded its uranium enrichment cap of 3.67% to just below 5%. Tehran has threatened to increase that to 20% enrichment or higher, a prospect that worries nuclear nonproliferation experts.

In response, foreign ministers gathered in Brussels on Monday to brainstorm ways to deescalate tensions and keep the 2015 deal afloat despite the withdrawal of the United States and a relentless maximalist campaign of U.S. sanctions.

“The risks are such that it is necessary for all stakeholders to pause, and consider the possible consequences of their actions,” the leaders of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom said in a statement Monday. “We believe that the time has come to act responsibly and to look for ways to stop the escalation of tension and resume dialogue.”

Iran expert Esfandyar Batmanghelidj sees Tehran’s move as “a gamble” that succeeded making Iran a priority at the highest level in Europe – the focal point of Monday’s meeting and high-level diplomacy by France. French President Emmanuel Macron dispatched his top diplomatic adviser to Tehran in a bid to jump-start talks to avoid uncontrolled escalation or even an accident.

The most tangible and visible step that Europe has taken to date is the establishment of Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX), a complex bartering mechanism to facilitate humanitarian trade between Iran and Europe that deliberately skirts U.S. measures. This solution was developed by the governments of the E-3 in consultation with the European Union after European banks signaled their unwillingness to risk cross-border transactions with Iran in the face of U.S. sanctions pressure. Getting it off the ground has been technically complex.

“From a European perspective, this is unparalleled,” notes Ms. Esfandiary. “They’ve never had to set up this kind of mechanism before. They’ve never had to stand up to U.S. sanctions before.”

It has also been politically fraught with the United States even threatening to sanction EU officials connected to INSTEX. This complicates buy-in from companies that might have U.S. interests, although it would be a good instrument for multinationals already present in Iran. Even a scaled-up INSTEX, the analysts concur, can only help mitigate – not completely offset – the impact of U.S. sanctions on Iran.

The limits of INSTEX

But while INSTEX became operational at the end of June when test transactions were carried out, it has simply not worked fast enough in the eyes of Tehran.

“Iranians understand that Europe is making some efforts, but there is this sense that it is simply not enough in view of the economic hardship that is being caused for the country,” says Mr. Batmanghelidj, founder of media company Bourse & Bazaar, which tracks economic developments in Iran. “There are inherent limits on what Europe can do particularly because the focus of what Iran is looking for is on the economic side.”

And it is unlikely, for both technical and political reasons, that oil exports will be plugged into the system as Iran would like.

“INSTEX alone is not going to be the silver bullet that convinces Iran to reverse or remedy its actions that are not compliant,” says Ellie Geranmayeh, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa Program at the European Council on Foreign Relations. “It is going to require a package.”

That package would have to include Chinese purchases of Iranian oil at a price and under conditions that don’t completely undermine Iranian interests. It is also going to require nuclear countries like Russia and China to continue the cooperation on Iran’s nuclear facilities. And it is going to require some of the new rounds of Iranian sanctions since April to at least be eased for a period of time, she says.

“The least worst option”

A challenge is the different strategic outlooks between Europe and Iran. For Iran, the JCPOA is a priority issue. Not so for the Europeans who need to keep the United States on their side strategically – especially on defense issues and NATO.

“If the Europeans are not willing or able to deliver something substantial to Iran, it means we need to get pragmatic and choose the least worst option ahead,” adds Ms. Geranmayeh.

“In my view that’s about a kind of JCPOA-lite arrangement where you keep the cornerstones of the deal in place. That means that at least some period of time … you get a freeze on Iran’s nuclear escalation and in return you give Iran the minimal, marginal economic steps that you are able to give.”

The EU is a major trading partner for Iran, with almost 21 billion euros’ worth of imports and exports in 2017. The bloc, says Mr. Batmanghelidj, needs to signal to Iran that there is a road map and institutional support for a continued Europe-Iran economic relationship and a growing one in the future.

Besides INSTEX, the European Union has adopted a financial support package for Iran. The governments of Austria, the Netherlands, and Sweden have also pushed forward with economic cooperation with Tehran.

“The problem is that all of these disparate efforts have not been packaged in a strategy,” says Mr. Batmanghelidj.

Snapbacks

While Europe is quietly sympathetic to the logic of Iran’s gambit, it could also trigger the JCPOA’s “dispute resolution mechanism” if pushed too far. The mechanism allows signatories to “snap back” economic sanctions on Tehran if they find that it wasn’t meeting its commitments under the agreement.

The analysts say this would be premature given that Iran waited more than a year after the U.S. pullout from the deal to reduce its compliance. But Iran’s gradual and calculated escalation also provides justification for voices within European governments that the deal with Iran is no longer viable.

“European officials cannot appear as lenient to an Iran that has violated the deal to its domestic constituents,” adds Mr. Batmanghelidj. In the long term, Iran risks sanctions snapback, whether that’s European Union or United Nations sanctions.

This scenario would bring joy to the anti-Iran hawks in Washington and Tel Aviv who are drumming for military confrontation with Tehran. It appears unlikely in the short term, as President Donald Trump and Iranian leader Hassan Rouhani have both signaled their aversion to an all-out confrontation. Nonetheless, the growing rift between Washington and Tehran has severely tested the diplomatic wherewithal of European powers.

As united as they are on wanting to salvage the JCPOA, there is only so much they can achieve in the absence of a change of heart in the White House.

“I don’t think the Europeans stand a chance reasoning with the U.S.,” says Ms. Esfandiary. “Their best bet is to unify and stand strong … a) to defend their own interests and b) to show that, OK, the appeasement period is over and now we disagree with Washington, so we’re going to do what’s best for us.”

Q&A

What Hong Kong’s man without a mask wants you to know

How do you understand a faceless movement? Brian Leung – the only Hong Kong protester to remove his mask and address the media – talks about his generation’s identity, and what comes next.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Suzanne Sataline Contributor

If you know one face from the Hong Kong protests, it’s probably Brian Kai-ping Leung’s.

On July 1, a few hundred protesters stormed the city’s legislative chambers, most hiding their faces behind cloth and paper masks. But hours later, as many started to trickle out, one young man stood on a desk and ripped off his mask, urging the crowd to stay, and stay unified.

Mr. Leung knows something about division, after watching Hong Kong’s last big social movement, 2014’s Umbrella Revolution, splinter into factions.

“I know very strongly that the movement can’t end this way, in a scenario where escalation and use of force ends without justification,” he says today.

That night, though, his plea was unsuccessful. But he instantly became the iconic image of the night – a night that represented principled activism to some, and chaotic vandalism to others. It’s put a question mark over Mr. Leung’s future plans, and he refuses to discuss his location.

But as Hong Kong continues to protest, attempting to preserve its autonomy under Beijing’s “one country, two systems” arrangement, Mr. Leung spoke with the Monitor about the pro-democracy and “localist” activism that has transformed Hong Kong – especially his generation. Here are selections from our conversation, edited for clarity and brevity.

What Hong Kong’s man without a mask wants you to know

On July 1, after a month of mostly peaceful protests, dozens of young people smashed the windows and doors of the city’s legislature, and hundreds more stormed the chambers.

Someone blacked out “People’s Republic of China” on the city’s emblem. Portraits were defaced. Many people scrawled slogans onto pillars and walls, including demands that the city government kill a proposed extradition agreement with mainland China – the bill that propelled an estimated 2 million people to march in June, pushing back against Hong Kong’s eroding autonomy.

While many protesters hoped the break-in would spark an occupation, most started to leave once police imposed a deadline. In a room filled with helmeted people, their faces hidden behind cloth and paper masks, one young man stood on a desk and ripped his off. As journalists filmed, he urged the crowd to stay. It was an unsuccessful plea, but instantly an iconic image of the protest – a night that represented principled activism to some, and chaotic vandalism to others.

“If we retreat now … they will film all the destruction and mess inside LegCo, point the finger towards us and call us rioters,” said Brian Kai-ping Leung. “Our whole movement cannot be divided. If we win, we all win together. If we lose, we will lose for 10 years. The whole civil society will turn back 10 years. ... Therefore, this time, we need to win, and win together.”

Mr. Leung knows something about division. The city’s last big social movement, a 2014 campaign for more expansive voting rights and elections free from Beijing’s grip, split into factions, some of which persist. Participants divided along generational lines and tactics, with some goading the more peaceful, nonviolent strikers to abandon that approach.

Mr. Leung wasn’t a well-known figure in that movement, but made his own mark. As an undergraduate at the University of Hong Kong, he edited a journal that published a provocative edition in 2014. Articles in “Hong Kong Nationalism,” published as a book the following year, asserted that the territory was a nation. That claim, coming amid President Xi Jinping’s campaign to tighten Hong Kong’s loyalty to China, inflamed then-chief executive Leung C.Y., who criticized the publication in his annual policy address. The book sold out and helped fuel a philosophy of “localism” that promoted Hong Kong’s language, culture, and history as distinct from mainland China’s.

Until mid-June of this year, Mr. Leung defended his master’s thesis at the University of Washington, where he’s a doctoral candidate studying economics, civil society, and democracy. On June 16, he flew home to join the protests. When he removed his mask on July 1, he took a risk.

“I think everyone knows very dearly and clearly that the one who spoke in front of camera and media is going to pay a price,” he says. He has refused to disclose his current location.

Using two social media apps, Mr. Leung spoke to the Monitor about his politics, his studies, and the activism that has transformed Hong Kong – especially his generation. Here are selections from our conversation, edited for clarity and brevity.

What message did you want to send to the world by storming the legislature?

It’s a culmination of desperation and frustration and the cry of democratic freedom from a large group of young people. They have no choice. They have exhausted all means of peaceful protest. We have tried a million-person protest, 2 million people marches, all sorts of advertisements in foreign media; we tried noncooperation. July 1 is an extension of the frustration and exasperation as to how the government responded inadequately to our demands.

Why occupy on July 1, a holiday marking Hong Kong’s handover from Britain to China? Lawmakers were not in the building.

July 1 is supposed to be symbolic or emblematic of the implementation of “one country, two systems,” a celebration of having a democratic government that belongs to the Hong Kong people. … After the return of sovereignty [young people] feel alienated and excluded and barred from that system.

Why did you decide to address the people in the room?

If we ended that night without really justifying our action in a statement or a declaration, I think it would end bitterly. Not only would it invite criticism from the Beijing camp, we would invite a lot of internal debate about the meaning and justification.

Was your decision spontaneous?

Very much so. What I saw was that people were wandering around, people were trying to protest in their own way, by defacing the emblem, doing some sort of graffiti, slogans, but I think people were also leaving. I felt the momentum shifting against us. I saw a moral vacuum that demanded someone stand up.

I witnessed from personal experience how a movement’s end can divide a civil society for years to come. … I know very strongly that the movement can’t end in this way, in a scenario where escalation and use of force ends without justification … and causes the dissolution of civil society for years to come.

Now that [Hong Kong chief executive] Carrie Lam suspended the anti-extradition bill, but did not withdraw it as protesters asked, what is next for the movement?

The success of this movement so far has to do with the repertoire, the arsenal of multiple weapons or tools or multiple creative ways to engage in protest. It’s taking money out of a Chinese bank. Boycotting a pro-Beijing company. ... Doing an occupation action.

At least we have to channel part of the energy into institutions and threaten the power of the pro-Beijing camp.

I also expect there might be sustained mobilization around the issues of police brutality, and ironically, more chances for confrontation between citizens and the police, hence more police brutality. More pressure will be built up on the police, and the government hiding behind it.

How would you describe your politics?

In 2014 I was a very strong [Hong Kong] localist. I still have a lot of attachment to that label, the rise of localism coincided with the rise of youth politics in 2014.

Over the past few years there’s been a strong consensus about identity. We reject the values imposed by the Chinese. … People in this movement act on the basis that we are Hong Kong people and we are willing to reject the Chinese way of doing things. I would not describe myself as pro-independence.

Do you plan to return and stay in the United States?

The Umbrella Movement is really the defining moment in my youth and many of my peers. We care so much about democracy in Hong Kong and freedom in Hong Kong that we are trying to think what is the best way to contribute to Hong Kong. The sole purpose of doing a Ph.D. is to come back to Hong Kong and find a position in a university. I really like teaching people. It excites my soul to know I could help Hong Kong students in some way.

Personally I’m very worried about the possibility of continuing my studies. And I’m very worried about the dream that I might not be able to come back to Hong Kong and be hired in an institution and contribute to Hong Kong in the way I imagined.

It will be politically very unreasonable for them [the Hong Kong government] not to charge me. Because I did what I did.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct an error in one of Mr. Leung’s quotes. He said, “We have tried a million-person protest, 2 million people marches, all sorts of advertisements in foreign media; we tried noncooperation.”

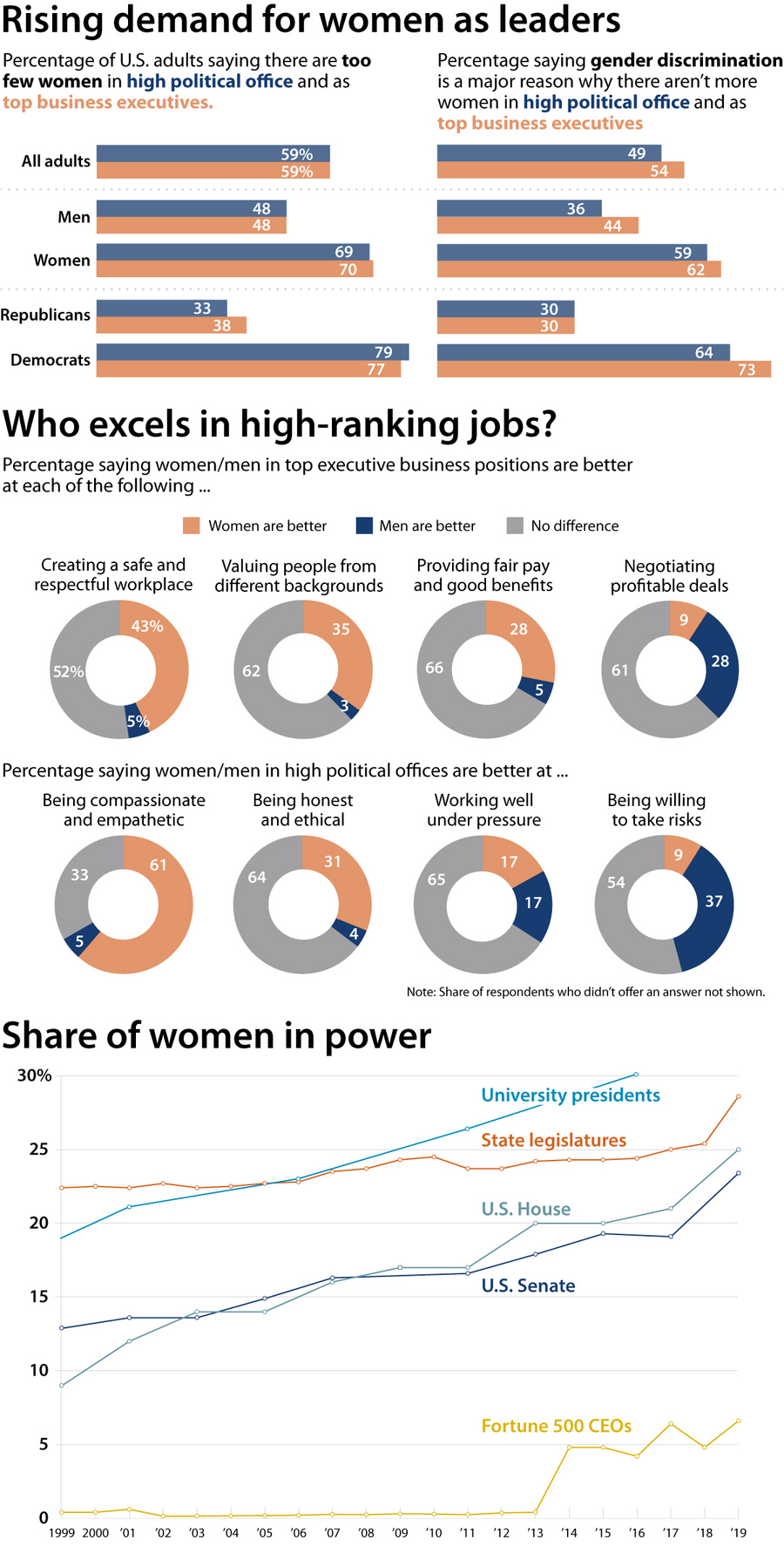

Picture a top executive. If you see a woman, you’re not alone.

Stereotypes are persistent, but they also bend based on real-life experience. When it comes to gender and leadership, Americans increasingly value the qualities women bring to the podium.

Attitudes about gender and leadership have been changing among men and women alike. Back in 1975, for example, about 6 in 10 of both women and men said they preferred their boss at work to be male, according to polling by Gallup. By 2017, that percentage had fallen by more than half, with most men and a plurality of women seeing “no difference” on the issue.

Why the change? In a study released today by the American Psychological Association, researchers point to women’s growing presence in the workforce and in colleges as key factors.

“As the roles of women and men have changed ... so have beliefs about their attributes,” lead author Alice Eagly said in releasing the study.

Today a majority of U.S. adults view women and men as equals on a number of leadership traits, such as being persuasive, according to Pew Research Center surveys. And people who do see gender differences now tend to give women the edge.

Yet Dr. Eagly says men are still perceived to rank higher in agency or ambition. And women still lag far behind men in actually filling top posts. “What’s the problem?” asks Gallup chief operating officer Jane Miller in a recent commentary. One answer, she says, is that “few organizational cultures are giving women (and men) what they need to raise families and rise to leadership.”

– Mark Trumbull, staff writer

Pew Research Center; Fortune (for women CEO totals)

Film

‘Excited with life’: David Crosby talks sobriety, love, and second acts

What happens when people defy society’s expectations about retirement? David Crosby discusses what led him to a creative and spiritual rebirth, a renaissance captured in a new documentary about his life.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Veteran musician David Crosby shows no signs of slowing down. His recent years have been filled with multiple new albums and a project first suggested by a friend: a documentary.

“David Crosby: Remember My Name,” includes events such as Woodstock and the founding of the band Crosby, Stills, and Nash. But it isn’t merely a chronological recap of Mr. Crosby’s life. “We wanted to go a lot deeper,” the musician says in a phone interview. “It’s a very honest documentary.”

It’s not only a cautionary tale but also an inspirational one. It chronicles Mr. Crosby’s change of outlook following a period in prison and his embrace of sobriety. He realized that his family and music are the most important things to him.

His songs today range from those about drone bombings and the plight of Syrian refugees to love songs penned for his wife of 32 years, Jan. Ultimately, Mr. Crosby views time as his most precious currency. He intends to spend it well.

“I gotta use the voice and I gotta write the songs and I got to do this the best I can. It’s here to be done. I’m gonna do it.”

‘Excited with life’: David Crosby talks sobriety, love, and second acts

David Crosby belies F. Scott Fitzgerald’s claim that there are no second acts in American lives. A former member of the Byrds and Crosby, Stills, and Nash, the veteran songwriter is enjoying a late-career renaissance. He’s released four acclaimed solo albums since 2014. A fifth is halfway finished.

Now, the musician’s creative and spiritual rebirth is the subject of a documentary, “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” directed by his friend A.J. Eaton. “He kept saying, ‘You know there’s this weird thing going on with your life here. There’s a big resurgence in your 70s when everybody else is shutting down the shop and moving back home. And why? What the heck? I want to do a documentary about it,’” recalls Mr. Crosby in a phone interview.

As much as Mr. Crosby loves his home life, retirement doesn’t interest him. He’s aware that, after a period of chronic drug abuse, he’s fortunate to be alive. The joy he still gets from singing is precious to him because he doesn’t take it for granted.

“I am definitely excited with life,” says the musician. “If you could look at what I’m looking at right now – the trees I’m looking out at in the sun here in the afternoon in California – that’s really a good picture of how I feel.”

The film project gained momentum when rock journalist-turned-filmmaker Cameron Crowe (“Jerry Maguire,” “Almost Famous”) offered to do the on-screen interviews. Mr. Crosby says Mr. Crowe has known him since he was 15. “He knows where all the bones are buried,” the songwriter says, chuckling.

The documentary unearths them all. Mr. Crosby serves as a tour guide through his past by revisiting landmarks such as the house where Crosby, Stills, and Nash formed (they knew they had a unique sound within 40 seconds of first playing together) and where they later recruited Neil Young.

The narrative spans the Woodstock festival, the making of Mr. Crosby’s 1971 psychedelic folk classic “If Only I Could Remember My Name,” and his relationship with Joni Mitchell. (“In the long run, people are going to say Joni was probably the best singer-songwriter of her times,” he says now.) Yet the documentary isn’t merely a chronological recap of Mr. Crosby’s life.

“It’s not just, ‘Oh yeah, and then he had this hit, and then I did that, and then I invented electricity,” says Mr. Crosby. “We wanted to go a lot deeper and that’s what we did. It’s a very honest documentary.”

Mental and physical journey

Inevitably, there are startling moments – beyond just early photos of Mr. Crosby before he grew arguably the most famous mustache in rock. The musician offers unstinting reflections of his descent into drug addiction and subsequent run-ins with the law. In December 1985, for instance, he failed to show for a court hearing. Wanted by the FBI, he fled across the country. Once he arrived at his derelict yacht in a marina near West Palm Beach, Florida, he spent several days taking stock of his life. Then he walked into an FBI office and turned himself in. But the real surrender was inside his own thought.

“There is a definite moment when you decide you can’t take it anymore and you give up. You’re going to do whatever it takes to get free” of addiction, says Mr. Crosby. “We know there is a moment, ‘the moment of clarity,’ we call it in the 12-step programs. It’s so well known that everybody keeps trying to document it and figure out how it happens. ... You know, because we want to be able to duplicate it. We want to save people’s lives.”

The documentary’s not only a cautionary tale but also an inspirational one. It chronicles Mr. Crosby’s change of outlook following a period in prison and his embrace of sobriety.

“Don’t mess with hard drugs. That’s definitely a big lesson,” says Mr. Crosby. “I’ve realized that there are certain things that are really important to me – my family and the music – and that I really shouldn’t let anything else distract me from those things.”

The artist readily admits he hasn’t been easy to work with. “Remember My Name” reveals that Mr. Crosby’s most famous musical compatriots, Graham Nash, Stephen Stills, and Neil Young, have fallen out with him. Do his former bandmates know that he loves them?

“I expect they don’t,” says Mr. Crosby. “And I do, but I don’t think they know that.”

Songwriting and politics

When the band imploded, he took a small trove of unrecorded songs with him. Those tunes have surfaced on recent solo records. Mr. Crosby is also quick to credit his creative renaissance to younger collaborators including his son James, singer-songwriters Becca Stevens and Michelle Willis, and Michael League, the leader of the popular jazz band Snarky Puppy. “They are really good writers. I’m really picky about who I do it with,” he says.

He’s drawn to political topics: drone bombings, money in politics, and the plight of Syrian refugees. “I don’t want to get involved in the cause of the week,” he says. “I reserve it for the things where my sense of moral outrage is involved and I can’t shut up.”

Mostly, though, he writes about love, including songs about Jan, his wife of 32 years. “I’m as in love with her as I was the day I fell in love with her,” he says.

Mr. Crosby views time as his most precious currency. He intends to spend it well.

“I gotta use the voice and I gotta write the songs and I got to do this the best I can. It’s here to be done. I’m gonna do it.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Healing the social wounds behind Ebola

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Nearly a year after the second-worst outbreak of the Ebola virus began, the World Health Organization has declared an “international health emergency,” its highest level of alert. The virus keeps advancing in Congo despite new types of medical prevention. Yet the WHO decision also suggests the crucial need for a nonmedical solution: building trust among local people to lessen their fears.

False rumors, a resentment toward outsiders, and conflict by armed militias have led to hundreds of health workers being attacked. In May, the United Nations decided to try a more humane and holistic approach. “Medical expertise is not sufficient to end epidemics,” concluded Tamba Emmanuel Danmbi-saa, humanitarian program manager at Oxfam.

By focusing on local fears and beliefs as well as understanding local concerns, WHO and others may now find the trust they need to not only end the outbreak but also heal social wounds. The real emergency is not international. It is in the hearts of the Congolese.

Healing the social wounds behind Ebola

Nearly a year after the second-worst outbreak of the Ebola virus began, the World Health Organization has declared an “international health emergency,” its highest level of alert. The virus keeps advancing in Congo despite new types of medical prevention. Yet the WHO decision also suggests the crucial need for a nonmedical solution: building trust among local people to lessen their fears.

“The inability to build community trust has proven a major barrier to stopping the spread of this disease,” says the International Rescue Committee’s vice president for emergencies, Bob Kitchen.

False rumors, a resentment toward outsiders, and conflict by armed militias have led to hundreds of health workers being attacked. According to a Harvard University survey, 1 in 4 people believe the virus was fabricated for financial or political gain. In the meantime, nearly 1,700 people have died since the outbreak began last August.

WHO says dealing with the situation is one of the most challenging humanitarian emergencies it has ever faced. “To build trust we must demonstrate we are not parachuting in to deal with Ebola and leaving once it’s finished,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of WHO.

In May, the United Nations decided to try a more humane and holistic approach. “Medical expertise is not sufficient to end epidemics,” concluded Tamba Emmanuel Danmbi-saa, humanitarian program manager at Oxfam. The U.N. assigned an emergency response coordinator, David Gressly, who has experience in Congo with local conflicts.

As a result, more Congolese are leading the official response. The affected communities are being consulted more. And those who survive the disease are being tasked to calm fears. In addition, the international community is more aware of the need to address the poverty and instability that feed the outbreak.

By focusing on local fears and beliefs as well as understanding local concerns, WHO and others may now find the trust they need to not only end the outbreak but also heal social wounds. The real emergency is not international. It is in the hearts of the Congolese.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The inspiration to get things done

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

What can we do when the task at hand seems overwhelming? For one woman, it was turning in prayer to the divine Mind, God, that enabled her to accomplish just such a task with joy, without stress, and on time.

The inspiration to get things done

We all have things to do from time to time that demand inspiration, direction, and a willingness to push through resistance to getting started.

This happened to me when, after deciding to make a big move from the United States to France, I had the task of emptying out and selling the contents of my home. The project seemed colossal and overwhelming.

I have seen how turning to God in prayer can help me move past anxieties of all kinds, including the fear that I can’t do what needs to be done or do it well. So I prayed for direction on how and where to start.

While praying, I remembered a line from the Bible, in the book of Isaiah. The King James Version puts it this way: “The word of the Lord was unto them precept upon precept, precept upon precept; line upon line, line upon line; here a little, and there a little” (28:13).

How comforted I felt reading this! To me it was clear direction. Christian Science explains that God is the unlimited divine Mind, and we are the creation – or inspired spiritual idea – of that Mind. Right thoughts and activities proceed from divine Mind and are reflected in us as God’s creation. This indicates that we have at every moment the inspiration and ability we need to accomplish good.

Even a glimpse of this fact can lift the fear that we don’t know how to start, opening us to an awareness of infinite possibilities. And that’s what happened. I had 1,930 square feet of house to empty, repair, carpet, and paint – and two months in which to do it. With my heart open to the inspiration of Mind, God, I was able to accomplish at least one task each day, and ultimately the project was completed in the allotted time. Further, the work was accomplished with joy and without stress.

That lesson learned in prayer has stayed with me. I have since found that a daily practice of affirming everyone’s true nature as the spiritual expression of God’s intelligence and goodness ensures that we always have the ideas needed to accomplish whatever task it is ours to do, whether large or small. This proved especially helpful when I began writing and blogging regularly and needed to come up with ideas and articles on deadline.

Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy once wrote, “There is but one way of doing good, and that is to do it!” (“Retrospection and Introspection,” p. 86). But we’re not left on our own to do so. Turning in prayer to God to lead us can open the way to accomplishing whatever needs to be done and is worth doing. As Mrs. Eddy wrote in her poem “Christ My Refuge”:

My prayer, some daily good to do

To Thine, for Thee;

An offering pure of Love, whereto

God leadeth me.

(“Poems,” p. 13)

A message of love

Sailing, take me away

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when we’ll explore the ethical implications of Neuralink, Elon Musk’s effort to connect human brains to a computer. In the meantime, we have a bonus read from today’s Monitor Breakfast with Rep. Tom Emmer of Minnesota.