- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Drones in space: Can a helicopter take flight on Mars?

- Vilified abroad, popular at home: China’s Communist Party turns 100

- Biden pushes democracy abroad as a matter of national security

- Does the future of social media really hinge on these 26 words?

- ‘Nomadland’: A wispy, affecting vision of life on the road

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How Texans helped turtles – and each other

For millions of Texans, it’s been a week of unusual cold and darkness. It has also called forth the unquenchable warmth and enduring light of kindness and compassion.

As snow and freezing temperatures swept the state, neighbors checked on neighbors, opening their homes and sharing supplies or assisting with errands. Out on the slippery streets, people used shovels and shoulder power to keep cars from getting stranded.

Rescue efforts extended to the shoreline, where sea turtles were stunned by the frigid temperatures. Ed Caum, executive director of the South Padre Island Convention and Visitors Bureau, found himself the unexpected caretaker of thousands of turtles, brought by the truckload or one at a time. “We’ve collected a lot, now we’ll try to save ’em,” he said.

“People do care. It makes you happy inside that there is good out there,” Margie Taylor, a Houston area resident who lost power and heat, told the Houston Chronicle.

Chris Lake, a Lutheran pastor, came to her rescue with an extra generator that could power a space heater. While assisting homeless people and others in the area, Mr. Lake and his teenage son needed aid themselves. Their truck got stuck, but strangers paused to pry it loose.

Such acts, multiplied across the state, were what enabled many people to get through an often harrowing week. (Henry Gass, our snowbound reporter in Austin, will be writing about the electric grid challenges in tomorrow’s Daily.) The gratitude encompassed the givers as well as the receivers.

The opportunity to help was “deeply meaningful,” Mr. Lake said. “To have my son be with me to see some of this stuff was pretty amazing.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Drones in space: Can a helicopter take flight on Mars?

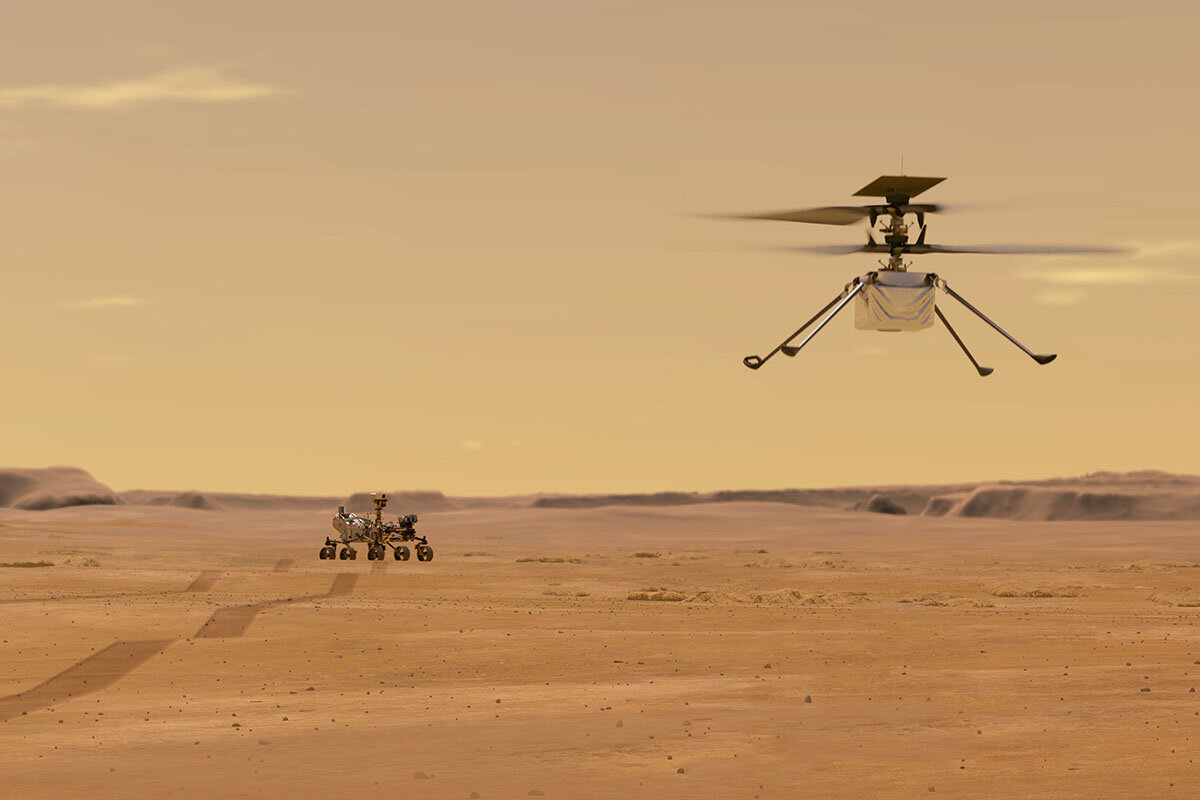

The quest to explore beyond our home planet tests humanity’s know-how, but also kindles hope and teaches lessons back on Earth. With today’s Mars landing, a rover called Perseverance and a helicopter called Ingenuity exemplify this spirit.

NASA has done it again. This afternoon, the agency stuck a landing on Mars for the 6th time.

The latest Martian rover, Perseverance, did not arrive alone. A hitchhiker came along for the journey, strapped to the belly of the rover. Named Ingenuity, the tiny helicopter is experimental technology, and weighs just 4 pounds. Beginning this spring, it will attempt to take to the Martian skies, marking the first powered flight of any craft on another planet.

Successful test flights could mean that helicopters will become an important part of the suite of tools sent to explore the red planet going forward. They would add a bird's-eye view to our understanding of Mars, and could serve as a scout for rovers – or even humans, one day.

“Science isn’t always at an easy landing site. It isn’t always an easy terrain,” says Doug Adams, an aerospace systems engineer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory who is not working on Ingenuity. “And helicopters, or rotorcraft, give you that flexibility to take your platform to the science and to observe where you might want to go to collect the science.”

Drones in space: Can a helicopter take flight on Mars?

It’s getting busy on Mars.

Today, NASA successfully landed its 6th probe on the surface of our neighboring planet, and earlier this month both the United Arab Emirates and China also had spacecraft arrive in orbit to study Mars. Altogether, nearly 50 spacecraft have been sent to explore Mars over the past half century.

NASA’s Perseverance rover could fundamentally change how we see the red planet and our place in the universe over the course of its mission, as it seeks out signs of past life. But it is not alone. A hitchhiker came along for the journey that could also make history in its own right.

Strapped to the belly of the Perseverance rover is a tiny, lightweight helicopter. Named Ingenuity, the flying envoy is experimental technology. Beginning this spring, it will attempt to take to the Martian skies, marking the first powered flight of any craft on another planet.

If the test flights are successful – or even if they’re not – Ingenuity could open up tantalizing new possibilities for how we explore the red planet and other parts of the solar system in the future.

“Science isn’t always at an easy landing site. It isn’t always an easy terrain,” says Doug Adams, an aerospace systems engineer at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory who is not working on Ingenuity. “Science doesn’t come to you. You have to go to the science. And helicopters, or rotorcraft, give you that flexibility to take your platform to the science and to observe where you might want to go to collect the science.”

A feat of a flight

To the annoyance of some and delight of others, similar technology flies all over tourist destinations on Earth: drones. So it might seem like a simple feat to send a tiny helicopter to Mars, too.

But there are a few key differences between Mars and the Earth.

Mars has an atmosphere that is about 1% the volume of Earth’s. That means that anything on Mars experiences significantly less pressure than on Earth. The gravity on Mars is also roughly a third of that on Earth.

The Ingenuity team has honed the helicopter’s design here on Earth, doing their best to simulate the Martian environment in special pressurized chambers. To combat the gravity issue, they added a tether to the top of the helicopter to reduce its weight.

To mitigate these differences, Ingenuity was built from very light materials, but with longer, stiffer rotors that spin faster than they would need to on Earth. The space helicopter weighs 4 pounds, sits about 19 inches tall, and its rotor system spans about 4 feet.

“We feel pretty confident that we can fly,” says Tim Canham, senior software engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the operations lead for Ingenuity. But there could be surprises on Mars that weren’t in the simulated environments.

To figure out how to get around, Ingenuity can’t just pull up Waze or GoogleMaps on Mars, either. And not just because we don’t have road maps for the red planet ... yet. GPS relies on a network of satellites in orbit around our planet, which doesn’t exist on Mars. Furthermore, Mars has a weak and irregular magnetic field. On Earth, compasses rely on the planet’s strong magnetic field to orient themselves.

Instead, Ingenuity will use an optical navigation system. Essentially, the craft will snap pictures of its surroundings as it flies to detect and identify features on the planet. It will rely on those images to orient itself and figure out how to get where it’s programmed to go.

A further hurdle for the helicopter is something that all spacecraft on Mars struggle with: power. While a rover can rest in the sunshine to charge its batteries on solar power if it needs to, a helicopter requires more and constant power to keep its body airborne. It’s a balancing act with weight.

Ingenuity will rely on solar power, as other options are prohibitively heavy. It will operate autonomously, but use the Perseverance rover to relay data and receive commands from mission control back on Earth.

The helicopter will perform five tests, if all goes well. The first three will test its basic flight and navigation capabilities, and the final two will push it to its limits to see where they may lie for space helicopter development.

A future filled with space helicopters

NASA has been billing this as a Wright Brothers moment. Indeed, powered flight on another world would be historic.

But Erik Conway, historian at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says that the first Mars rover – Sojourner in 1997 – might be a better analogy.

Sojourner was also a technological test. It only traveled about 330 feet from the Pathfinder lander that it accompanied, but it opened the door for the many rovers that have come since and revolutionized our view of Mars.

Mr. Canham agrees that Ingenuity is a “baby step” toward following the same development path of the rovers. “Nobody’s ever flown a rotorcraft outside Earth’s atmosphere, much less on Mars,” he says.

Other NASA engineers will be watching closely as Ingenuity begins spinning its rotors through Martian air. Johns Hopkins’ Dr. Adams is one of them. He is spacecraft systems engineer for NASA’s Dragonfly mission to Titan, a moon of Saturn. Dragonfly, which is currently in development for a projected 2027 launch, will be a rotorcraft lander mission to study the conditions under which life might have first emerged.

Titan and Mars bear some similarities – namely weak magnetic fields – but there are also differences. Titan, for instance, has a much denser atmosphere than Mars. Dragonfly will also need to be much more massive than Ingenuity to carry all the scientific tools needed, as the Titan probe will not be a technological test. Still, Dr. Adams says the success (or even failure) of an autonomous helicopter on another world will help Dragonfly.

“We will learn something from Ingenuity’s experience, regardless of what that is,” he says. “And, you know, the best case scenario is very good. And even in the worst case scenario, we benefit.”

On Mars, successful test flights could mean that helicopters will become an important part of the suite of exploration tools. They would add a bird's-eye view to our understanding of the planet, and could serve as a scout for rovers – or even humans, one day. They could scope out the landscape much more quickly than a rover and determine whether it was navigable terrain, or even worth exploring.

And perhaps space helicopter technology, like rovers before it, will enable us to discover something that changes the way we see our universe.

“We’ve learned a great deal in my lifetime about the solar system,” Dr. Conway says. “What I was taught from textbooks in the ’70s is turning out not to quite be right.”

“When we first were able to send spacecraft to Mars, there was this image of Mars as potentially habited. And that gets blown up by a mission [about 50 years ago],” he explains, referring to NASA’s Mariner 4, the first mission to successfully fly by Mars. Since then, we’ve learned that Mars is neither as dynamic as we first surmised nor as static as early missions led us to believe. And there is still much to discover about our neighboring planet.

A deeper look

Vilified abroad, popular at home: China’s Communist Party turns 100

While China’s leaders are criticized abroad, economic success and curbing COVID-19 have bolstered the Communist Party's popularity at home. But challenges loom on the eve of the party’s 100th anniversary.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Last winter, as the novel coronavirus began to take over headlines, China’s Communist Party appeared to be facing an unprecedented challenge. At home, there was widespread outrage with Beijing’s initial mishandling of the pandemic. Abroad, too, opposition was rising.

But today, on the eve of the party’s centennial, China’s government has pulled off a stark turnaround. Its economic output grew in 2020, the only major world economy to expand. And its curbing of COVID-19 contrasted sharply with bungled responses abroad, swelling domestic support. Even as it turns increasingly autocratic, the party’s longstanding recipe for legitimacy still works: achieving concrete development goals, like a massive poverty alleviation campaign.

But Beijing knows it will face difficulty retaining this mandate as the population ages, economic growth slows, and debt increases. The party’s quest to retain legitimacy drives much of China’s behavior at home and abroad – and could unravel if it doesn’t meet rising expectations.

“The party’s leaders believe they have a narrow window of strategic opportunity to strengthen their rule ... before China’s economy sours, before the population grows old, before other countries realize that the party is pursuing national rejuvenation at their expense,” says retired Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, former U.S. national security adviser.

Vilified abroad, popular at home: China’s Communist Party turns 100

A year ago Feb. 7, China’s brave coronavirus whistleblower Dr. Li Wenliang died after treating patients in Wuhan, triggering an unprecedented online torrent of grief and anti-government rage along with calls for freedom of speech.

The widespread public outrage over the government’s initial mishandling of the virus outbreak and suppression of Dr. Li’s warnings amounted to what longtime observers called an existential crisis for China’s Communist Party and Xi Jinping, its leader since 2012.

Angry residents brazenly heckled a visiting party Politburo member. Some yelled “it’s all fake” from their apartment windows during the draconian lockdown in Wuhan, the city of 11 million people that is now estimated to have suffered half a million cases and at least 3,800 deaths.

But only five months later in August, with the virus under control, a jam-packed pool party in Wuhan with DJs and dancers in neon tutus was captured in a viral video – a testimony to China’s success in largely quashing the outbreak at home. By January, China’s rapid economic recovery saw the country emerge in many ways stronger from the pandemic year. Its economic output grew by 2.3% in 2020 to become the only major world economy to expand.

This stark turnaround has shored up popular support for the party inside China, bolstering the belief of Mr. Xi and other leaders that China’s authoritarian system is resilient and on the rise, despite a sharply negative turn in attitudes toward Beijing in Western democracies. “The best criteria” for judging a country’s system, said Mr. Xi, sitting with folded hands before a huge mural of the Great Wall in a virtual address to the World Economic Forum Jan. 25, is whether it delivers “political stability, social progress, and better lives.”

Indeed, as the Communist Party prepares to celebrate its 100th anniversary this summer, experts in China and abroad are delving into why the country’s increasingly autocratic regime enjoys such domestic popular support, especially as Mr. Xi tightens party controls and his own personal grip on power.

“How do you now explain the fact the CCP [Chinese Communist Party] at least appears to be fairly resilient?” says Edward Cunningham, director of Ash Center China Programs at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Overall, popular satisfaction with China’s government has grown stronger over the past 20 years, according to Dr. Cunningham and other Harvard researchers who led an independent, multiyear survey of Chinese public opinion. The 2003 to 2016 study drew on face-to-face interviews with more than 31,000 people in urban and rural China, but did not include most ethnic minorities or migrant workers. In 2016, fully 93% of those surveyed expressed satisfaction with the central government, with 32% saying they were “very satisfied.” That same year, 70% of respondents voiced approval for their local governments, which deliver most public goods and services, marking a significant increase from 44% in 2003.

These trends are likely continuing today, says Dr. Cunningham, pointing to anecdotal evidence. “The recent COVID case is a useful example,” he says. “At the outset, citizens were unhappy with the local government response, but as the central government engaged in lockdowns and the situation improved, satisfaction with central government actions rose, eventually spreading to views of local government as well.”

China’s swift curbing of the virus contrasted sharply with bungled responses in the United States and other developed countries, swelling domestic support for the regime, experts say.

“Within China itself, when they apply the lens of China’s response to the virus, both in public health and economic terms and political terms, versus the American management of the virus domestically and many other Western countries, it has further consolidated Xi’s hold on the Chinese leadership,” says China scholar Kevin Rudd, president of the Asia Society.

Popular satisfaction in China should not be underestimated, says Elizabeth Economy, author of “The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State.” “The vast majority of Chinese feel a lot of pride in how their country has developed economically, and in the greater role China now plays on the global stage,” says Dr. Economy, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in California.

Still, the latest developments also shed light on how the country’s authoritarian leadership, even while amassing greater power and control with a high-tech surveillance state, must continue to respond to popular needs, complaints, and pressure. With a population of 1.4 billion, China faces serious demographic, environmental, and economic problems going forward. The party’s often-obscured quest to retain legitimacy drives much of China’s behavior at home and abroad – and could unravel if it doesn’t meet rising expectations.

“China has politics, too,” says David Lampton, senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Institute at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

How this political dynamic evolves in the world’s flagship communist state will have major geopolitical implications for the world over the next decade and beyond.

Delivering the goods

When A Bo was growing up in a high mountain village in China’s southwestern Yunnan province in the 1970s and ’80s, his family was so poor that they had to eat wild fruit and herbs. One dirt road led to his village, and when heavy summer rains turned it to mud, travel was all but impossible.

“We were always hungry,” he recalls. Today, with government help, Mr. A Bo’s family and many others in his village have worked themselves out of poverty. He raises ducks, pigs, and cows on a small farm and works at construction and other odd jobs. His village has running water and paved roads. And while his modest income “doesn’t count as very good, it’s a lot better than before,” he says with a laugh.

In December, Mr. Xi announced that China had eradicated extreme poverty in Yunnan and across the country, completing the massive task of lifting 850 million people out of destitution since 1981. The milestone offers one powerful example of how Mr. Xi and the party continue to gain legitimacy for their authoritarian rule in the eyes of China’s people.

“The government helped us build houses ... and gave us livestock to raise,” says Mr. A Bo. “If we didn’t have their help, we wouldn’t have paved roads or running water, so the common people are relatively happy.”

As a result, rural people and migrants with lower incomes, such as Mr. A Bo, have been a key source of support for China’s central government, multiple surveys show, constituting essentially an important political base for the party.

“There is a very high degree of satisfaction in rural low-income areas for the Chinese Communist Party,” says Matthew Chitwood, a U.S. fellow with the Institute of Current World Affairs, who recently returned from living for two years in Yunnan’s remote mountain village of Bangdong. There, he says, “Xi is the poster child of the party and the poverty eradication campaign.”

“My neighbors in Bangdong are living their best lives now,” he says. “Their lives have dramatically improved from even five years ago, and they attribute that directly to the party.”

Indeed, satisfaction levels since the early 2000s have risen most among China’s poorer residents like Mr. A Bo, signaling that despite growing inequalities created by economic reforms, marginalized people are not a swelling source of political resentment, the Harvard survey found. “There is still little evidence of a ‘social volcano’ of bottom-up discontent,” says Dr. Cunningham.

The anti-poverty campaign trumpeted by Mr. Xi is one example of the party’s overarching strategy of “performance legitimacy.” Under Chairman Mao Zedong, the party rallied support around Marxist-Leninist ideology and waging the 1949 revolution. But after Beijing launched market-oriented economic reforms in 1978, the party adopted a more pragmatic strategy to maintain public backing by achieving concrete development goals.

This performance legitimacy approach is rooted in China’s ancient, dynastic concept of the Mandate of Heaven, which emperors could retain or lose depending on how well they governed, says Dingxin Zhao, dean of the sociology department at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, China.

Today, the Communist Party works to secure this mandate above all through robust economic growth and “delivering the goods” – from roads to jobs, Dr. Cunningham says.

The party has also bolstered its rule though social policies aimed at reducing inequalities unleashed by economic reforms. These include rural health care, free education, agricultural subsidies, and poverty alleviation. “Social policy ... has contributed decisively to the regime’s stability and general support of the regime,” says Dr. Zhao.

Another popular policy has been Mr. Xi’s anti-corruption drive, launched soon after he took charge in 2012. “From the minute he became general secretary of the Communist Party, [Mr. Xi] talked about the need to root out corruption,” which he said “could mean the death of the Communist Party and the death of the Chinese state,” says Dr. Economy.

Rampant official corruption unleashed along with China’s market-oriented economic reforms has stirred deep public discontent. More than half of Chinese surveyed in 2011 described local government officials as “unclean” or “very unclean,” ineffective, and favoring the wealthy, the Harvard survey shows, dismaying villagers such as Mr. A Bo.

“It was chaotic,” says Mr. A Bo, who recalls corrupt local officials setting up roadblocks and charging tolls, or restricting the water supply.

Mr. Xi responded with the most sweeping anti-corruption campaign in modern China – arresting thousands of party and government officials of all ranks. Although the campaign was also viewed as part of Mr. Xi’s efforts to purge opponents and consolidate power in his own hands, it sharply curbed official abuses encountered by the public, surveys show.

Today, local thugs no longer control roads around Mr. A Bo’s village. “Now those people don’t dare do that ‘underworld’ activity, or they will be arrested,” says Mr. A Bo. “Now it’s peaceful ... and everyone can use the roads.”

Double-edged sword

Such concrete gains in prosperity and well-being, and progress on problems ranging from corruption to environmental pollution, have boosted the party’s performance legitimacy nationwide – including among China’s new middle class.

Mr. Zhang, a retired private entrepreneur who was born and raised the son of a factory worker in Beijing, is on the lower rung of this emerging tier. Among the fastest growing in the world, China’s middle class swelled from about 3% of the population in 2000 to more than half, or 700 million people, in 2018.

Mr. Zhang (who asked to withhold his first name to protect his privacy) has benefited not only from China’s economic boom, but from housing security and government spending on his health care and pension. He sums up popular attitudes with a simple story typical of his generation. “When I was small, all we wanted was to be able to fill our stomachs. ... Then, gradually, you could eat well. If you wanted to eat an apple, you could buy an apple. If you wanted to eat meat, you could buy meat,” he says.

In Mr. Zhang’s eyes, steadily rising living standards equate to Beijing doing a good job. “If my life is better day by day, if year by year it’s going in a good direction, then what do I have to be upset about?” he says.

“Of course,” he adds, Chinese people still complain about things around the dinner table. “Above all, we curse about Chinese officials’ corruption. But what country doesn’t have ‘bad eggs?’” he asks, using Chinese slang for “scoundrel.”

Today, such sentiment buoys Mr. Xi politically as the Communist Party nears its July centennial. “By the end of 2020, Xi Jinping had recovered his political position comprehensively,” says Mr. Rudd, the former prime minister of Australia. Mr. Xi is further entrenching his power with the aim of effectively becoming China’s “leader for life” at the next party congress in 2022, he says.

Yet despite the current strength of Mr. Xi and the party, experts point out that performance legitimacy is inherently fragile. It depends upon a continuous, tangible improvement in people’s material well-being. Ever rising expectations create both positive energy and risky tensions – a double-edged sword for the party and its limited resources. “Performance legitimacy relies too much on performance,” says Dr. Zhao. “Your relationship with the people is ... transactional. People judge you ... day by day, case by case.”

One major obstacle to raising living standards is the sheer size of the low-income population: 600 million of China’s 1.4 billion people have a per person income of only about $150 a month, according to official data. Although the party has achieved its poverty alleviation target – a very low bar – it now faces the harder task of shrinking the income gap between urban and rural China, and between the coast and hinterland.

“You basically have two different Chinas and two different economies operating,” says Dr. Economy. “So when do you begin to take care of the people who have been left behind?”

Beijing knows it will face increased difficulty retaining this performance-based mandate as the population rapidly ages, economic growth continues to slow, and stimulus financing dramatically increases debt. Moreover, China faces rising opposition overseas, where unfavorable public opinion toward Beijing has reached its highest level in 12 years and the lack of confidence in Mr. Xi has surged, according to a Pew Research Center poll of 14 countries with advanced economies in North America, Western Europe, East Asia, and Australia.

“The party’s leaders believe they have a narrow window of strategic opportunity to strengthen their rule ... before China’s economy sours, before the population grows old, before other countries realize that the party is pursuing national rejuvenation at their expense,” says retired Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, former U.S. national security adviser and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Rolling back reform

On a sunny October morning in Shanghai, Jack Ma, co-founder of e-commerce giant Alibaba and one of the richest men in China, took to the podium at a global finance summit and made a bold call for innovation of China’s financial system.

China’s banks exhibit a “severe pawnshop mentality” that hurts entrepreneurship, he said, criticizing the nation’s financial regulators as anachronistic. “We shouldn’t use the way to manage a train station to regulate an airport,” Mr. Ma said. “We cannot regulate the future with yesterday’s means.”

Soon after, Mr. Ma was reportedly dressed down by regulators and then disappeared mysteriously from public. The highly anticipated initial public offering of Alibaba’s financial technology arm, Ant Group Co., was halted and the firm placed under investigation, reportedly on the orders of China’s top leader Mr. Xi. In January, after missing major appearances, Mr. Ma resurfaced in public for the first time in months in an online video of a small local ceremony.

The incident demonstrated how, in Mr. Xi’s China, Beijing will not tolerate constructive criticism – even from a top entrepreneur such as Mr. Ma. The imperative of party power and control means subordinating everyone and everything, including top business magnates and their firms.

Facing uncertain economic growth, China’s post-Mao leaders have looked for alternative ways to secure Communist Party rule into the future. After launching market-oriented economic reforms in 1978, leader Deng Xiaoping and his followers moved to bolster legal sources of legitimacy by strengthening government institutions, promoting a meritocracy, setting standards for a smooth leadership succession, and allowing new avenues for political participation.

In a 2009 paper, Dr. Zhao warned that moves toward “legal-electoral legitimacy” were vital. Otherwise, Beijing would “face a major crisis when the Chinese economy cools off.”

But since 2012, Mr. Xi has moved in the opposite direction. “You had a very dynamic, vibrant political birthing process underway, and for Xi, that was very threatening,” says Dr. Economy.

Mr. Xi has rolled back political reforms, strengthened ideological indoctrination and censorship, and tightened party controls. He has concentrated power in his own hands to a degree not seen since Mao – ending term limits and paving the way for his lifelong rule.

Under Mr. Xi, the party has also reined in big companies and curtailed civil society by shuttering nongovernmental organizations. He has jailed activists, from feminists to human rights lawyers, and imposed broad population control measures such as facial recognition surveillance and a social credit system that rates citizens’ behavior. Harsh crackdowns have arbitrarily detained an estimated 1 million Uyghurs and members of other predominantly Muslim ethnic groups in the western region of Xinjiang, while curtailing basic freedoms and purging pro-democracy elected officials, students, and others in Hong Kong.

Yet by monopolizing power, Mr. Xi also positions himself as a singular point of blame for any national crisis or setback that can’t be deflected onto local officials. Indeed, Mr. Xi himself is fixated on domestic opinion, prioritizing it over international events, says Steve Orlins, president of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, a nonprofit that promotes engagement between the countries. “President Xi gets up in the morning and he ... gets briefings on Tibet, Xinjiang, Chengdu, Wuhan,” he says. “The Chinese view the threats as internal.”

Ultimately, the increased repression can stifle, but not destroy, pressures from members of China’s increasingly urban, educated, middle class for a greater say in their futures. “Even authoritarian governments have to respond to the elites in their society,” says Mr. Orlins.

Discontent over the direction Mr. Xi is moving the country runs deep among some Chinese, from intellectuals and entrepreneurs to migrant workers and activists. Others in China’s creative class feel broader reforms are needed for people to realize their full potential.

Tu Guohong lives quietly as an independent artist, writer, and art scholar in Chongqing, a megacity neighboring China’s southwestern Sichuan province. A graduate of an art school, Mr. Tu uses Western-style oil painting to depict working-class Chinese in traditional urban settings. His subject matter is varied, though. He is especially proud of a series of portraits depicting former President Barack Obama as a Chinese peasant.

Asked about his views on the overall level of support for the government, Mr. Tu, who says he doesn’t generally talk about political problems, chooses his words carefully.

“I don’t know what most people think, but they seek a happy life,” he says.

“As for myself, I want China to follow Deng Xiaoping’s road of reform and opening. Not only economic reform, but also cultural – a nation’s development is not just dependent upon the economy, but also on the humanities,” he says. “China should not go backward.”

*This story was updated to state the correct administrative status of Chongqing, China. It is a municipality and not part of Sichuan province.

Patterns

Biden pushes democracy abroad as a matter of national security

President Biden has restored democratic rights to a central role in U.S. foreign policy. This may take time to bear fruit, but the new administration considers it crucial to America’s own future.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ned Temko Correspondent

The first signs of international response to President Joe Biden’s move to make human rights and democracy central to U.S. foreign policy are not entirely encouraging.

To be sure, Saudi Arabia has released a prominent political prisoner, and the Egyptian government freed a prominent critic’s relatives.

But this week Egypt detained them again, and in Myanmar the generals have taken power again in a coup. Hungary just revoked the license of one of its few remaining independent radio stations, and there is no sign that either Moscow or Beijing will pay much heed to Washington’s strictures.

That will not deter the new U.S. president. He seems to have concluded that in today’s world, where anti-democratic China is a rising power, it is in America’s national security interest to make common cause with its major allies to support human rights and democratic values.

During the Cold War, these were the issues that served as ideological dividing lines with the Soviet Union. They have been clouded more recently by U.S. actions in Afghanistan, Libya, and Iraq. President Biden hopes to restore their luster.

Biden pushes democracy abroad as a matter of national security

They are blips on the radar screen, scattered across the globe. But taken together, they constitute an early sign of the impact – and limitations – of America’s move to reassert human rights and democratic accountability as core values of its foreign policy.

So far, the limitations are winning.

But that is “so far.” As with any exercise of soft power, the limitations always tend to be quicker to appear and easier to measure. It will take time to truly gauge the impact of the new U.S. policy, after four years during which the White House downplayed human rights as a policy priority.

There have been flickers of response to President Joe Biden’s change of direction.

Just weeks after Mr. Biden took office, Saudi Arabia freed one of its most prominent political prisoners, Loujain al-Hathloul, after more than 1,000 days of imprisonment.

In another Middle Eastern autocracy, Egypt, the signals have been mixed. Only days after the U.S. election, the government freed imprisoned relatives of a prominent Egyptian American human rights activist, Mohamed Soltan, who lives in the United States. But this week several of them were rounded up and jailed again.

And there’s been no sign of change in the “illiberal democracies” of Hungary and Poland on the eastern flank of the European Union. Hungary last week revoked the license of one of its few remaining independent radio stations.

Since Poland and Hungary are both NATO allies, and Egypt depends on U.S. security aid, Washington perhaps hopes to use its leverage to nudge them toward change. “We will bring our values with us into every relationship that we have across the globe,” a State Department spokesman said. “That includes with our close security partners.”

The administration will be less optimistic about having an early impact on Vladimir Putin’s government, which first tried to poison, and then jailed, opposition politician Alexei Navalny. In Myanmar, the army generals who have ousted the reelected civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi are unlikely to pay much heed to American demands that they step aside. The Chinese authorities seem impervious to U.S. strictures despite increasingly lurid news reports of the scale of their repression of the Muslim Uyghurs in the northwestern region of Xinjiang.

These governments would seem to have too much invested in their anti-democratic policies to change course. Their response to criticism has been pretty much what Washington will have foreseen: “Mind your own business.”

Still, there’s reason to look beyond this early score card.

President Biden is not the first U.S. leader to take office pledging to bake human rights and democratic values into his foreign policy agenda. These used to be the issues that served as ideological dividing lines with the Soviet Union. But since the end of the Cold War their importance has been clouded by controversies over avowedly pro-democracy military engagements in Afghanistan, Syria, Libya and, above all, Iraq.

This administration’s approach seems both narrower, and longer term. Narrower, because it’s a response to the growing influence that autocratic nationalists enjoy on the world stage – a trend the administration hopes to begin restraining, in alliance with other democracies. Longer term, because Mr. Biden will have no illusions that the tide can be turned easily or quickly – especially in the face of China’s growing economic weight and international reach.

He will also be aware of the arguments against a “values-based” foreign policy. Realpolitik, the term coined in 19th-century Germany, maintains that power lies at the heart of all politics. And the words of an English prime minister of that epoch, Lord Palmerston, offer another riposte. There are no “eternal allies” in foreign policy, he said, only eternal interests.

But the new U.S administration seems to have decided that in today’s world it is indeed in America’s national interest to make common cause with its major allies to support human rights and democratic values.

Administration officials have also suggested that a retreat from that commitment would further embolden autocracies and weaken democracies. In that context, Saudi Arabia’s early nod toward President Biden’s concern for human rights may be significant. Its de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, enjoyed former President Donald Trump’s fulsome embrace despite his harsh crackdown on dissenters.

Still, the deeper effects of America’s resumed commitment to human rights may become clear only years from now – a result of a message heard not so much in the halls of government as among street protesters. And in prison cells.

Natan Sharansky, an Israeli politician and former Soviet dissident, made that point not long before last year’s U.S. presidential election in urging world democracies to show “solidarity” with Hong Kong as a strand of what he termed a necessary response to “fear societies” like China.

He recalled how, during his imprisonment in the USSR, he heard that then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan had denounced the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” Those words, he said, had given him and other inmates reason to “hope.” He said that also explained why he’d denounced Mr. Trump’s comment, during the former president’s rapprochement with North Korea, that its leader, Kim Jong Un, “loves his people, and his people love him.”

Such statements, he said, undermined America’s “moral standing.” And they “dampened dissent” rather than inspired it. That kind of impact may be hard to measure, but it matters. Indeed for Mr. Sharansky, among the best-known Soviet dissidents of his generation, dissent is nothing less than “the most powerful unconventional weapon against dictatorship.”

The Explainer

Does the future of social media really hinge on these 26 words?

Who bears responsibility for online speech? The question is as old as the internet. Now lawmakers are looking to reform or repeal a piece of legislation that has long undergirded internet systems.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Members of Congress don’t agree on much these days, but there’s one idea both the right and the left support: Something needs to be done to rein in social media companies.

Democrats’ concerns revolve around harassment and misinformation, while Republicans’ focus is on political speech. Both sides have set their sights on a small but critical piece of federal law known as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. But such discussions have been clouded by fundamental misunderstandings of what CDA230 is and the role it plays in the legal functioning of the internet today.

This provision shields internet service providers from liability associated with defamatory content posted by users. Twitter and Facebook would be utterly unviable without CDA230. But it also benefits the little sites. An online guest book on a bed-and-breakfast website, for example, would be a legal time bomb for the B&B without CDA230. Here we explore the historic and current implications of the law, and some of the misconceptions that muddle the discussion.

Does the future of social media really hinge on these 26 words?

Members of Congress don’t agree on much these days, but there’s one idea both the right and the left support: Something needs to be done to rein in social media companies.

Democrats’ concerns revolve around harassment and misinformation, while Republicans’ focus is on political speech. Both sides have set their sights on a small but critical piece of federal law known as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. But such discussions have been clouded by fundamental misunderstandings of what CDA230 is and the role it plays in the legal functioning of the internet today.

What is CDA230?

The Communications Decency Act was a 1996 federal law meant to regulate pornography online. It was mostly struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court just a year later. Section 230 is one of the only remaining pieces of the act, but it has proved foundational to the internet.

This is its key text: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

Effectively, it provides internet services legal immunity for the illegal activity of their users (with a number of exceptions, including intellectual property and sex trafficking law). In other words, if you offer an interactive service online, and someone uses it to post content that opens them to legal liability, you are not open to that same liability yourself.

Why is that so important to the internet?

Let’s first look at publishing liability in traditional circumstances to establish a baseline. To get your message out to the public, you’d need to find someone to print it in their physical medium – say, a magazine. That magazine would have editors, typesetters, printers, and a slew of other people who’d all be involved in getting your words, which they’d have seen, out.

Now let’s say your words were an obviously malicious lie about your neighbor. Certainly you would be legally responsible for your libel. But because all those magazine staffers had the chance to exert editorial control over your words and they failed to do so, under defamation law the magazine would be legally responsible as well.

The internet began under that model. But web developers quickly figured out how to create pages that asked users to fill out forms, and the content of those forms would become new pages viewable by all – no human oversight needed. This led to bulletin boards, file transfer sites, image galleries, and all sorts of content that was completely user-driven.

But this poses a legal problem. Under traditional publishing liability, a service – say early dial-up provider Prodigy – could be liable for anything its users post. So if you again wrote something obviously defamatory about your neighbor, Prodigy would be on the hook.

But in the online world, Prodigy wouldn’t know a thing about your post before it went public. Prodigy editors never looked at it. Prodigy designers never placed user text on the page. All that was automated.

CDA230 bypasses this problem by allowing services to offer the automation necessary for the modern internet to function. It’s most obvious at the large scale; Twitter and Facebook would be utterly unviable without CDA230. But it also benefits the little sites. An online guest book on a bed-and-breakfast

website, for example, would be a legal time bomb for the B&B without CDA230.

But you said that traditional publishing liability is based on the publisher’s knowledge of the users’ words. Shouldn’t social media lose CDA230 protection when they start editing users?

This became a common criticism of Facebook and Twitter after they began to post warnings around misinformation by then-President Donald Trump and 2020 election deniers, and when they began removing their content. And it does make sense based on the traditional understanding of publisher liability: that it is a publisher’s knowledge of and control over a message that creates liability.

But there are a couple misunderstandings here.

Critics of social media companies argue that by editing and removing content, the companies have moved from the realm of “platform,” which is protected by CDA230, to “publisher,” which is not.

But there is no such distinction in CDA230. The law doesn’t mention the word “platform.” The closest it comes is “interactive computer service,” which has been interpreted to refer to everything from your cable company to social media companies to individual websites. The only mention of the word “publisher” is in reference to users, not interactive computer services. Services and users are the only categories the law references. There is no subcategory of “unprotected” service, i.e., what critics claim is a “publisher.”

Also, the argument that social media sites should lose immunity ignores the history that spurred CDA230’s creation.

Before CDA230, some courts did recognize that traditional publisher liability didn’t make sense when internet services were automated. But they applied that logic in situations when platforms tried to moderate users too.

In the case of Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Services Co., the court found that Prodigy was liable for a user’s defamatory post because it moderated user posts to create a family-friendly experience. In contrast, “everything goes” rival CompuServe did not moderate and was held not liable for users in Cubby, Inc. v. CompuServe Inc.

Those rulings set up a perverse incentive to let litigious user material prosper, since moderating it would only invite lawsuits. For companies that wanted to offer a pleasant experience, that might mean disabling user content entirely was the only option.

Enter CDA230. Indeed, the section quoted above is titled “Protection for ‘Good Samaritan’ blocking and screening of offensive material.” The point of CDA230 is to encourage internet service providers to moderate their users without fear of blowback.

But don’t social media companies need to be reined in? Shouldn’t we repeal CDA230 to force them to stop censoring people?

This is another common argument around CDA230: Its repeal or reform would restrain social media companies from what they’ve been doing with regard to Mr. Trump among others. Critics in Congress have recommended introducing requirements that CDA230 immunity be dependent on platforms being politically neutral, or limiting their moderation to certain subject matters.

There are a few flaws with this critique. First, CDA230 isn’t actually what allows social media companies to edit user content. That right is enshrined in the First Amendment. Even if CDA230 is repealed completely, Twitter still has the right to publish – and edit – content on its own platform.

There’s also a problem with attempts to reform CDA230. Part of First Amendment jurisprudence is a prohibition against content-based laws; that is, the government cannot pass laws that target expression based on its message.

That bar against content-based laws would very likely apply to any attempt to impose content requirements upon social media moderation, even if those requirements were to be “politically neutral.” Imposition of a “neutrality” requirement is inherently discriminatory against social media companies’ right to political advocacy, and thus very likely unconstitutional.

Lastly, a complete repeal of CDA230 would likely result in more moderation of user content, not less. With the end of CDA230 immunity, the major concern of social media companies would be to reduce potential liability. Once-borderline cases would be much more likely to be moderated, since the cost of overlooking them would be that much higher.

So what can be done about CDA230?

The better question might be whether CDA230 is truly the problem.

Democrats have proposed reforming the law as well, most recently in a bill put forward by Sens. Mark Warner, Mazie Hirono, and Amy Klobuchar. But while that bill targets immunity for harassment and discrimination rather than political bias, it’s just as problematic as the reforms proposed by conservative lawmakers. Legal scholar Eric Goldman writes that the bill’s “net effect will be that some online publishers will migrate to walled gardens of professionally produced content; others will fold altogether; and only Google and Facebook might survive.”

Digital rights advocates point to Big Tech’s dominance as the real issue, with the solution being more competition and transparency in the social media marketplace.

As a commentary from the digital rights nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation argued in November, “If Congress wants to keep Big Tech in check, it must address the real problems head-on, passing legislation that will bring competition to Internet platforms and curb the unchecked, opaque user data practices at the heart of social media’s business models.”

Before becoming Europe editor at the Monitor, Mr. Bright was the research attorney for the Digital Media Law Project at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University.

On Film

‘Nomadland’: A wispy, affecting vision of life on the road

Although set in the wake of the Great Recession, “Nomadland” has resonance now, notes film critic Peter Rainer. It considers the choices people make when faced with economic hardship in a way he calls “mysteriously moving.”

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

‘Nomadland’: A wispy, affecting vision of life on the road

The affecting, uneven “Nomadland,” set early in 2011 in the wake of the Great Recession but equally pertinent today, is a road movie of a very special sort. Fern, played by Frances McDormand, lost her husband a year after the closure of a gypsum factory in Empire, Nevada, that put nearly everybody out of work. Even the ZIP code of the town has been erased. With no desire to stay on, she packs up a camper and heads out across the high and low deserts, working seasonal jobs to get by.

She joins a migratory band of fellow travelers, a few of whom she befriends and reconnects with along the way. Some of these nomads, mostly older adults, choose to live like this because they believe they have no better way to survive. Others just like the peace and freedom.

Written and directed by Chloé Zhao, the film is based on Jessica Bruder’s 2017 nonfiction book “Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century,” and includes several of the book’s real-life vagabonds, such as the ailing, valiant Swankie and the irrepressible Linda May, playing variants of their actual selves. Fern is not based on any one individual, but her singularity, like a character from a Steinbeck novel, makes her seem both her own person and symbolic of a larger reality.

Nothing terribly dramatic happens in “Nomadland,” and at times this can make the film seem wispy and digressive – a piece of arty anomie with a semidocumentary overlay. The challenges of maintaining life’s basic necessities are downplayed. Fern faces few dangers: no hazardous encounters, no thefts, no violence. This seems more an idealization of her situation than a reality. Her biggest crisis comes when her camper breaks down and she cadges money for its repair from her sister Dolly (Melissa Smith), who lives with her husband and children outside Denver in conventional, and, in the film’s view, boring, middle-class comfort.

Fern reluctantly pays her a visit, and it is in this scene, more than halfway into the movie, that a bit of Fern’s family backstory unfolds. She left home as soon as she could, married hastily, and moved, according to Dolly, to “the middle of nowhere.” Not altogether convincingly, Dolly commends the “pioneer spirit” of the big sister she looked up to, whose departure years ago left a big hole in her life.

It is also in this Denver setting that the film tips its ideological hand, just as it did earlier when the real-life nomad guru, Bob Wells, regales his followers with talk of the “tyranny of the dollar.” Fern chastises Dolly’s husband, George (Warren Keith), a real estate broker, for encouraging people “to invest their whole life savings, go into debt, just to buy a house they can’t afford.” The implication is clear: Footloose Fern incarnates the spirit that made America great, a spirit that has been squelched in a mercenary economy gone bust. “I’m not homeless,” she tells people. “I’m houseless.”

Romanticizing Fern in this way glosses over her emotional complexity. Despite the film’s erratic attempt to pigeonhole her, it’s obvious that Fern’s wanderlust owes far more to psychological need than ideological persuasion. She quietly affirms several times a lasting love for her late husband, but the affirmation seemingly lacks conviction. When a fellow nomad, beautifully played by David Strathairn, attempts to get close to her, she barely registers the overture. As was also true of the vengeful mother McDormand played in “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” the role of Fern gives McDormand license to indulge an opaqueness that is often more gnomic than expressive. Perhaps she and Zhao felt that being more demonstrative would shatter the film’s wayward poetic mood.

They needn’t have worried because, despite the movie’s manipulations, that mood often comes through anyway. It’s there in the scenes where Fern is simply walking alone in a deserted RV park, or floating unclothed and unobserved in a mountain stream, or just watching a herd of bison from the window of her camper. In these moments, and others like them, “Nomadland” is mysteriously moving.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Nomadland” is available via theaters and streaming service Hulu on Feb. 19.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Blackouts in Texas put a light on how to make energy choices

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Record cold temperatures in Texas that left millions of people without power have also sparked a heated debate over the state’s energy future. At first, the debate was merely finger-pointing. But then the crisis turned to constructive action. Gov. Greg Abbott asked for an “emergency” review to improve the quasi-governmental entity that manages the power grid. Meanwhile, thousands of homeowners bought backup power units. Others searched for ways to add solar power to homes.

Many people began to discuss things they had long left to politicians and bureaucrats: energy reliability and resiliency, climate change, and, most important, how to reshape the bonds within their communities around the difficult choices over energy sources.

Tragedies often test the affections within a community. Texas could become a model for how citizens engage in reinventing their electricity sources, perhaps even bringing those supplies closer to their communities.

The lights are back on in parts of Texas. But in addition, Texans have turned on a giant switch to see how they can make better energy choices, starting with a more democratic and caring way of making such decisions.

Blackouts in Texas put a light on how to make energy choices

Record cold temperatures in Texas that left millions of people without power have also sparked a heated debate over the state’s energy future. At first, the debate was merely finger-pointing. Why didn’t private utilities plan ahead for the Arctic snap? Could the state’s grid operator have demanded more electricity capacity? Did Texas rely too much on wind turbines (that froze up) or on natural gas (whose pipelines also froze)?

But then the crisis turned to constructive action. Gov. Greg Abbott asked for an “emergency” review to improve the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), a quasi-governmental entity that manages the power grid. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission began its own probe for solutions. Meanwhile, thousands of homeowners bought backup power units. Others searched for ways to add solar power to homes.

Many people began to discuss things they had long left to politicians and bureaucrats: energy reliability and resiliency, climate change, and, most important, how to reshape the bonds within their communities around the difficult choices over energy sources.

As Californians discovered after wildfires and heat waves knocked out power last year, Texans have entered the age of “energy democracy.” They are suddenly peeking behind the curtain of electricity governance and thinking anew how to make choices over types of energy, how to transmit it, and how much to centralize or localize power sources. They are speaking with terms like “grid participation” and “user empowerment.”

“When this is all over, we will need to have a conversation – a serious conversation – about why we are where we are today,” said Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner.

The great blackout in Texas could transform the character of its democracy. “The building of solutions to future energy needs is also the building of new forms of collective life,” wrote Timothy Mitchell of Columbia University in a 2011 book, “Carbon Democracy.”

Texas has plenty of precedents in the United States to follow. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, New Orleans came together in new ways to revamp public education and build new types of inexpensive houses. A 2007 mega-tornado in Greensburg, Kansas, prompted a new civic unity that turned the rural town into a model for renewable energy.

Tragedies often test the affections within a community. With U.S. electric utilities set to invest about $1 trillion in the power grid by 2030, Texas could become a model for how citizens engage in reinventing their electricity sources, perhaps even bringing those supplies closer to their communities. “The value of resilience and decentralized, localized supplies of power has only grown in the public’s consciousness,” states a 2019 study by the nonprofit RMI.

The lights are back on in parts of Texas. But in addition, Texans have turned on a giant switch to see how they can make better energy choices, starting with a more democratic and caring way of making such decisions.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Wings like a dove

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Keith Wommack

Is there any escape from horrible weather? This short podcast explores the idea that we have a God-given ability to escape storms that attempt to engulf us – to find the help we need, and to be ready to help others, too.

Wings like a dove

To hear Keith’s sharing, click the play button on the audio player above.

Originally published as a Sentinel Watch podcast on www.JSH-Online.com, Feb. 17, 2021. Sentinel Watch podcasts share spiritual insights and ideas from individuals who have experienced healing through their practice of Christian Science. There is currently no paywall for these podcasts, and you can check out recent episodes on the Sentinel Watch landing page.

A message of love

Still smiling

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today! Come back tomorrow: Taylor Luck is working on a story about how resource-poor Jordan is vaccinating refugees alongside citizens, out of a belief that until all of the most vulnerable are protected from the virus, no one is.