- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A year after Floyd unrest, a Minneapolis neighborhood emerges from ashes

- When Gaza guns fall silent, will new path to peace emerge?

- Parents eye another option for fall: Hybrid home schooling

- ‘No longer just the white man.’ Can French literature make room for new voices?

- Fewer fights: Well-managed resources help keep conflict at bay

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

George Floyd legacy: A teen activist takes stock

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Mavis Rudof was just 13 when she realized what she wanted to do with her life.

It was June 11, 2019, and she watched from the courtroom gallery as her public-defender father argued for the freedom of Darrell Jones, a Black man who had been convicted of murder by an all-white jury in 1986. When the jury, this time with two Black jurors, came back with a not-guilty verdict, she knew.

“I got into the car with my dad after the verdict ... and was like ‘this is the work I need to do,’” she recalls.

I met Mavis when she was a student in my preschool classroom. When I caught up with her a year ago, cellphone footage of George Floyd’s death had just emerged and Mavis could no longer wait to add her voice to calls for racial justice. She joined protests and solidified her resolve to “obstruct the injustice that we are living in right now,” as she told me at the time.

A year later, former police officer Derek Chauvin has been convicted of Mr. Floyd’s murder. In Mavis’ view, “tremendous change” is still needed. “Our first police officers were slave patrols,” she says. “That says a lot about how our systems have been built.”

At a societal level, she says the verdict opened “a window of possibility for changes. It showed that convictions can happen.”

These hopes have been buoyed by the public discussions of justice, privilege, and racial equity over the past year. “White people need to be forced to think about these issues,” she argues. “Black people live it every day.”

Her advice to white people wanting to better understand these issues? “Listen to people of color. And learn. ... If race is hard to talk about, then you are probably having the right kind of conversations.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

A year after Floyd unrest, a Minneapolis neighborhood emerges from ashes

A neighborhood in Minneapolis, heavily damaged during protests a year ago, is trying to rebuild in a way that embodies ideals of diversity and equality, potentially offering a new model for urban redevelopment.

When unrest in Minneapolis spread to the city’s Longfellow neighborhood last year, Ruhel Islam opened his restaurant, Gandhi Mahal, for medics to treat injured protesters. The next night, rioters set fire to the police building and dozens of businesses in Longfellow, and by dawn, his restaurant lay in ashes.

In a Facebook post that went viral the same morning, his teenage daughter, Hafsa, quoted him as saying, “Let my building burn, justice needs to be served, put those officers in jail.”

His words resonate a year later as more than an expression of forgiveness. Mr. Islam has helped form a neighborhood collective called Longfellow Rising that intends to rebuild the triangular, three-block zone that included Gandhi Mahal to further elevate – and celebrate – the neighborhood’s racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity.

The discussions that gave shape to Longfellow Rising yielded a governing principle that people of color would form the heart of the initiative and guide its progress. “I’m not interested in going back to ‘normal,’” says Meena Natarajan, artistic and executive director of Pangea World Theater and a member of the collective’s board. “I think we can build a better community, a better city.”

A year after Floyd unrest, a Minneapolis neighborhood emerges from ashes

Former customers might regard the empty dirt lot where the Indian restaurant once stood as a burial plot for an immigrant’s dream. In 2008, eight years after moving to Minneapolis and a dozen after arriving in America, Ruhel Islam realized the aspiration he had carried with him from his native Bangladesh. Defying the Great Recession, he opened Gandhi Mahal in the Longfellow neighborhood on the city’s south side, his path through the economic gloom lit with energy and optimism.

Mr. Islam’s restaurant soon gained a loyal following and citywide reputation for its vibrant cuisine and inviting ambience. In the dead of winter, when all lies fallow on the Minnesota tundra, he harvested peppers, spinach, tomatoes, and herbs from an aquaponics garden he built in the basement. Praise for his chicken tikka masala, palak paneer, and other classic Indian dishes spread beyond Minneapolis, eliciting satiated raves from Guy Fieri, who visited Gandhi Mahal in 2016 for his Food Network show “Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives.”

The restaurant’s success added to the gradual renaissance of Longfellow. The neighborhood of 5,000 residents, located a 10-minute drive from downtown Minneapolis, began to grow in size and diversity in the 1990s after stagnating for two decades as white residents departed for the suburbs. A steady flow of immigrants from Africa, Latin America, and South Asia settled in Longfellow and adjacent neighborhoods to raise families and re-imagine their future.

Little reason existed for residents or business owners to wonder if the area’s revival would continue – until last May, when in the span of four days, a quarter century of progress went up in flames.

A bystander’s video captured Derek Chauvin, then a Minneapolis police officer, kneeling on the neck of George Floyd as two other officers held him down and a fourth stood watch. Mr. Floyd’s death on Memorial Day ignited protests that exploded into riots, and as vandals wrought destruction across the city, their rage crested in Longfellow.

The four officers worked out of the 3rd Precinct station, a block from Gandhi Mahal, and during the first two nights of unrest, Mr. Islam opened his space for medics to treat injured protesters. The next night, rioters set fire to the police building and dozens of businesses in Longfellow, and by dawn, his restaurant lay in ashes.

The grace he showed in the face of personal loss earned him recognition far beyond the renown of Gandhi Mahal. In a Facebook post that went viral the same morning, his teenage daughter, Hafsa, quoted him as saying, “Let my building burn, justice needs to be served, put those officers in jail.”

His words resonate a year later as more than an expression of forgiveness. Mr. Islam has helped form a neighborhood collective called Longfellow Rising that intends to rebuild the triangular, three-block zone that included Gandhi Mahal to further elevate – and celebrate – the neighborhood’s racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity.

The initiative exemplifies a model of redevelopment known as inclusive design that emphasizes public involvement and community cohesion. The racial justice movement has drawn attention to the concept as cities attempt to redress chronic economic and social inequities between minority and white residents.

The nonprofit group in Minneapolis consists of business and landowners, faith leaders, economic developers, and other community partners inspired by dual desires to stave off gentrification and promote economic equity for people of color. The effort to transform an area known to locals as Downtown Longfellow will seek to support and attract minority business owners, expand affordable living options, and create public and private spaces that embody ideals of racial justice and social equality.

The conviction of Mr. Chauvin in April on charges of second- and third-degree murder and manslaughter defused the lingering unease in Minneapolis without resolving the racial disparities brought to light by last year’s upheaval. Mr. Islam describes Longfellow Rising as a chance to set an example for the city by rooting the neighborhood’s renewal in the soil of unity. In his view, rather than a mass grave of ruined ambitions, his empty lot and those nearby represent a community garden where a shared vision of hope will flourish.

“We want people to come here to heal and grow through community, through art, through food,” he says. “I feel change happening, and I believe we can come up with something extraordinary.”

The protests that cascaded across Minneapolis revealed a solidarity between Longfellow’s merchants and residents. Downtown shopkeepers handed out bottled water and hand sanitizer to demonstrators and posted signs in windows calling for an end to racial injustice. Residents sought to keep watch over small businesses when riots erupted and later returned with brooms and trash bins to help store owners clear away debris and salvage belongings.

“This has long been an area where neighbors look out for each other. The unrest solidified that bond,” says Ingrid Rasmussen, lead pastor at Holy Trinity Lutheran Church and a member of Longfellow Rising’s board of directors. Church volunteers ran a distribution site to hand out food, clothing, and other donated goods for weeks after the disorder, and since early spring, Holy Trinity has flown a Black Lives Matter flag above its complex.

“There’s a sense we’ve never been so connected,” she says. “Out of tragedy has arisen a sense of responsibility to one another.”

Rioters damaged or destroyed 1,500 businesses across Minneapolis and St. Paul, inflicting an estimated $500 million in losses. The casualty list in Longfellow ranged from grocery, drug, and department stores to cafes, coffee shops, and restaurants, along with the post office, a medical clinic, and an apartment building under construction.

The neighborhood’s downtown nestles in one crook of the intersection where Minnehaha Avenue meets Lake Street, a major commercial artery in South Minneapolis. Across the intersection, Target and a pair of grocery stores, Aldi and Cub Foods, have reopened since completing repairs. Construction has started on an AutoZone shop, a Wendy’s restaurant, and the apartment complex, all of which burned down last spring.

The recovery of corporate-owned businesses contrasts with the struggle of independent merchants to rebuild or finish repairs. The limited emergency funding provided by the city to small businesses in Minneapolis – about $7 million to date – forced many owners to pay for cleanup and removal of rubble. High construction costs and an uncertain economic climate jeopardize their ability to move forward.

“It’s been a disappointing response from city officials,” says Chris Montana, who with his wife, Shanelle, co-owns Du Nord Craft Spirits, five blocks from Longfellow’s downtown. Their warehouse flooded after vandals set a fire that tripped the sprinkler system. “We need allies. We need public officials to stick up for us.”

The state Legislature has proved less obliging than the city, with Republican lawmakers opposing a $300 million relief package for Twin Cities businesses, contending that Minneapolis officials mishandled the crisis a year ago. In the meantime, Longfellow has relied on its own resources and communal goodwill, much as occurred during the protests, when police pulled back as the neighborhood burned.

The Montanas established a recovery fund for Longfellow businesses that collected $750,000 in donations, and they distributed grants of $5,000 to $15,000 to dozens of recipients. The money enabled a Latino-owned barbershop in downtown to reopen and defrayed cleanup costs for a damaged restaurant run by a Somali family.

“But it’s nowhere near enough to meet the need,” says Mr. Montana, one of the country’s few Black distillery owners. He plans to launch a small-business incubator in the coming months to encourage minority ownership. “We want to see people of color running their own businesses and owning their own property. That’s how we can keep the neighborhood from gentrifying.”

Longfellow’s ethnic restaurants, tree-lined streets, and lower cost of living relative to most of Minneapolis had attracted a mix of young families, downtown workers, and retirees. The prospect of losing business owners of color who had nurtured the community’s reawakening surfaced as an early concern among neighborhood leaders after the protests.

Their initial conversations acted as a catharsis. In time, they recognized that the unwanted devastation and lack of city and state support presented an opportunity to recast the area’s destiny.

The discussions that gave shape to Longfellow Rising yielded a governing principle that people of color would form the heart of the initiative and guide its progress. Meena Natarajan, artistic and executive director of Pangea World Theater and a member of the collective’s board, likens the work to mounting a stage production – with a community cast of thousands.

“The first question you always have to answer in theater is, ‘What does it mean to create a sense of belonging?’ You have to create shared understanding to build trust in one another,” she says.

The liberal reputation of Minneapolis shrouds historical disparities in income, education, and housing in a city where white residents make up 60% of the population of 440,000. Ms. Natarajan, who emigrated with her husband from India to the United States in 1987, considers Longfellow Rising an effort to interrupt a status quo that consigns people of color to the cultural and socioeconomic margins.

“I’m not interested in going back to ‘normal,’” she says. “I think we can build a better community, a better city.”

The coalition’s members joined forces to, in effect, hit “pause” on the typical redevelopment process that occurs in the wake of disaster and prioritizes reflexive replication of the past. The deliberate pace of planning has allowed the group to solicit and integrate public feedback and to focus beyond the coming year to the decades ahead.

The board hired a local design firm to assist with mapping out a new future for Downtown Longfellow by gathering ideas from residents, business owners, and other community members during a series of workshops this spring. The sessions served as a listening tour as participants dreamed out loud about resuscitating the area.

“So much about real estate tends to be, ‘You gotta act fast,’” says Jamie Schwesnedl, who co-owns Moon Palace Books, located a block from the barricaded, unoccupied police station. “That usually means you end up with a Subway shop, a cellphone store, a check-cashing place – maybe a Foot Locker if you’re lucky.” He explains that Longfellow Rising, instead of settling for “something that’s not terrible,” aspires to cultivate change on a generational scale.

“There’s this energy behind rebuilding and creating space for businesses owned by people of color and to have a cooperative approach,” says Mr. Schwesnedl, who serves on the coalition’s board. During last year’s protests, he rebuffed police officers who tried to commandeer his parking lot for use as a staging point, and he and his employees later posted a huge storefront sign that read “Abolish The Police.”

“This is a chance to build something in harmony with the memory of what happened here,” he says, “and to live the values of racial and social equality, not just talk about it.”

Longfellow Rising’s design plan strives to balance the version of downtown that fell to the flames with a new iteration that would rise from the ashes. The result could heal the neighborhood’s landscape and herald another renaissance.

Mr. Islam will rebuild Gandhi Mahal and add a food bank, an outdoor garden, and a shared community space to promote food justice and sustainable agriculture. Mr. Schwesnedl, who leases a pair of vacant lots next to his bookstore from his parents, will explore developing the properties with affordable housing and retail space for

minority-owned businesses.

Ms. Natarajan and Mr. Islam intend to collaborate on building a permanent home for Pangea World Theater on a lot adjacent to his restaurant where the offices of a nonprofit organization burned down. The multicultural theater company has earned acclaim for staging productions that examine themes of peace, human rights, and social justice, and Ms. Natarajan suggests that Pangea can provide emotional release for a community ruptured by collective trauma.

“What art gives us is an opportunity to come together to better understand each other,” she says, “and from that comes growth and compassion.” In that spirit, Longfellow Rising has commissioned a local Native American artist, Angela Two Stars, to conceive an interactive public artwork that will stand across from the police station. The tile installation will metamorphose from a cocoon into a butterfly over a period of months to symbolize the neighborhood’s ongoing transformation.

“Artists and the arts are a central force in the rebuilding of community,” Ms. Natarajan says. “People of color and communities of color are fighting to be heard, and we have the power to amplify those voices in our neighborhood.”

The coalition’s working proposal would establish a downtown plaza and other outdoor gathering spaces, improve pedestrian safety and access to public transit, and shift the area toward solar energy. The group’s emphasis on equity and sustainability wins praise from Minneapolis City Councilman Cam Gordon, who credits Longfellow’s business owners for persevering in the face of scarce public assistance following the riots.

“As a member of city government, it’s kind of unbelievable to me that we couldn’t do more to help them. I feel like we failed them,” says Mr. Gordon, whose ward includes Longfellow. He regards the nonprofit initiative as a possible blueprint for mending neighborhoods across the Twin Cities. “It’s a careful, thoughtful approach that shows local businesses and institutions can come together and be intentional about racial and social equality. It makes me hopeful.”

The strategy of inclusive design has infused life into languishing neighborhoods in Dallas, Detroit, Oakland, and elsewhere. An alliance of residents, community activists, and city planners in Pittsburgh banded together more than a decade ago to save a predominantly Black neighborhood hollowed out by urban renewal. The group received a $30 million federal grant in 2014 to build 350 units of mixed-income housing.

The funding required for that kind of ambitious project explains, in part, why inclusive design remains rare. The economic inequities between minority and white residents in large cities parallel a similar imbalance in the business world that extends to access to bank loans.

The struggle to obtain capital thwarts minorities from owning businesses and property, and complicates their efforts to rebuild in the event of a calamity.

“There is no margin for most business owners of color,” says Henry Jiménez, executive director of the Latino Economic Development Center in St. Paul. “If you get wiped out, whether it’s by a hurricane or riots, rebuilding is extremely difficult.”

In Longfellow, where neighborhood leaders worry about gentrification sweeping away minority businesses, two factors enhance the prospects of rescuing the downtown. A handful of Longfellow Rising’s board members own their properties, and Holy Trinity Lutheran Church has offered to act as a short-term land bank.

The church’s willingness to hold on to properties for as long as 24 months will give more time to business and land owners to line up financing, reducing the threat of foreclosure. Ms. Rasmussen describes the rationale for the decision in simple terms.

“We want to build back together,” she says. “We’re neighbors.”

Ade Alabi moved to Minneapolis more than 30 years ago to work as an engineer. The Nigerian émigré later tapped his life’s savings to enter the real estate business, and in January last year, he acquired a century-old brick building next to Gandhi Mahal for $2.8 million. The 32,000-square-foot space housed several minority-owned businesses, including a Latin nightclub, a Mexican restaurant, and a Spanish-language radio station.

In March, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down much of public life, and two months later, police killed Mr. Floyd. The building burned to the ground the same night as Mr. Islam’s restaurant.

After several months of waiting in vain for city aid, Mr. Alabi relates, he spent almost $500,000 from an insurance payout of $3 million on demolition and cleanup services. He estimates the cost of rebuilding would exceed $9 million.

“It’s a difficult situation and you feel unsure what to do,” says Mr. Alabi, a Longfellow Rising board member. He recalls the large gatherings for weddings and quinceañeras – a traditional Latin American celebration to mark a girl’s 15th birthday – that filled his building’s banquet hall.

“Yes, you can sell. But this was a place so important to the Latino and Hispanic communities,” he says. “I want to bring that back, to have events that make people happy. I want businesses run by people of color that are for people of color. Would another owner want that?”

The lack of city assistance pits his best intentions against financial reality, and with the uncertain timeline of Longfellow Rising, his lot and others could remain vacant over the summer. The scenario concerns Melanie Majors, executive director of the Longfellow Community Council, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“People talk about the need to heal. But driving through a wasteland doesn’t help people feel better,” she says. The boarded-up 3rd Precinct station intensifies the ambient discomfort. “The thing sits there as a horrible reminder of what happened and why it happened, and nobody from the city is telling us what they’re planning to do. It’s an abdication of responsibility.”

Still, as the city’s long year draws to an end, there are glimmers of a new dawn. A private-public fund unveiled in April will funnel $30 million to damaged neighborhoods for redevelopment projects. The Lake Street Council, a nonprofit advocacy group for businesses along the thoroughfare, has distributed $8 million to hundreds of merchants and property owners from a recovery fund amassed through individual and corporate donations.

“All of Minneapolis is having a reckoning,” says Russ Adams, who manages the council’s recovery initiatives. “There’s a need for both urgency and patience.”

For Mr. Islam, who absorbed the demise of his restaurant with uncommon equanimity, staying busy eases his anxiety. A few months after Gandhi Mahal burned down, he opened Curry in a Hurry, a delivery and takeout spot. He has turned his frustration over the city’s sluggish response into motivation to revive his adopted neighborhood. He is determined to see Longfellow rising.

“The city isn’t going to do it for us,” he says. “So we’ll do it and tell the city, ‘We did it.’”

Patterns

When Gaza guns fall silent, will new path to peace emerge?

It has been over 20 years since the U.S. was last involved in a serious effort to resolve the Palestinian issue. The current fighting between Israel and Hamas might – just possibly – prompt Washington to try again.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

At the heart of the current fighting between Israel and Hamas lies a paradox.

On the one hand, the fighting has shaken a widespread belief in Israel that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was fading away. It has put the idea of a “two-state” solution back on the table. On the other, both Hamas and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu are implacably opposed to any such negotiated compromise.

Both, at least for now, stand to emerge politically strengthened from the latest bloodletting. But in the longer term the outbreak of violence might – just might – prompt a renewed focus on trying to find a long-term compromise between Israel and the Palestinians.

That would demand an active role of America, Israel’s closest ally. President Joe Biden has shown no interest in expending political capital on what has historically proved to be a fruitless task: His foreign policy priority is China, not the Middle East. He will doubtless be profoundly dubious about launching a new U.S. diplomatic initiative there.

Still, the current fighting has raised another question at the heart of the Gaza paradox: whether the price of not doing so might be too high.

When Gaza guns fall silent, will new path to peace emerge?

Sadly, we’ve been here before: the militant Islamist Hamas movement in Gaza, on Israel’s southern border, firing missiles at Israeli towns and cities, Israel responding with overwhelming force, hundreds of innocent civilian lives lost, mostly Palestinian.

But while the military equation hasn’t changed, the political context has.

A critically important paradox lies at the heart of this latest round of fighting, the third major outbreak in the last dozen years. How it’s resolved will determine what happens when the guns fall silent again.

On the one hand, the fighting has shaken a widespread belief in Israel that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was fading away, and has put the idea of a “two-state” solution back on the table. On the other, both Hamas and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu are implacably opposed to any such negotiated compromise.

And both, at least for now, stand to emerge politically strengthened from the latest bloodletting.

Hamas will feel it has achieved what it was seeking last week by targeting missiles not just at nearby southern Israeli towns but also, crucially, at Jerusalem – the disputed holy city at the root of the current conflict, where Israeli police were clashing with protesters angered by the threatened eviction of a number of Palestinian families.

Hamas’ aim? To claim overall Palestinian leadership at a time when the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority on the West Bank has been drained of most of its authority at home and is finding it increasingly difficult to make its voice heard abroad.

For Mr. Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving leader, the showdown came at the most precarious point in his political career. Facing trial on corruption charges, he had failed to assemble a new governing coalition after a fourth indecisive election in two years. Rival politicians on left and right were working to form an alternative coalition – including, for the first time ever, a Muslim party representing Arab Israeli citizens.

Within days, the situation for Mr. Netanyahu changed. He was leading a country united by the need to bring an end to the Hamas rocket attacks. Opposition leaders suspended their coalition talks, with all potential partners aware they’d be risking the ire of their own constituents by launching a joint Jewish-Arab government amid the escalating violence.

The key question now will be on the other side of the paradox: whether the short-term political effects of the fighting give way in the months ahead to a renewed focus on trying to find a long-term compromise between Israel and the Palestinians.

That will depend not just on Israelis and Palestinians, but on outside powers such as Arab countries, the European Union, and above all Israel’s principal ally, the United States.

The prognosis: It could happen, but the obstacles are daunting.

First, the fighting has to end. If the template of past Israel-Hamas confrontations holds, that is likely to happen in the coming days: The Israeli military will step up attacks to destroy as many Hamas targets as possible, world pressure will build amid rising civilian casualties in tiny, densely populated Gaza, and Egypt will mediate a truce.

One early sign of the political winds will then come from Israel: Will Mr. Netanyahu’s rivals resume their efforts to form a coalition government, even one including Arab parliamentarians? If not, there is little chance of a parliamentary majority, and a fifth election might be on the way.

If that happens, will the Israeli-Palestinian conflict be a major campaign issue, unlike the last four elections?

A weakened Palestinian Authority would welcome a renewed push for a negotiated compromise, with the prospect of a PA-led state made up of the West Bank and Gaza Strip alongside Israel. So, too, would European countries and much of the international community. They’ve never wavered from their commitment to the two-state formula.

But the critical player will be America. Former President Donald Trump broke with decades of U.S. policy by shunting aside the two-state idea and backing Mr. Netanyahu’s right-wing nationalist coalition in its bid to cement open-ended Israeli control of the West Bank.

The Trump administration also mediated groundbreaking peace deals between Israel and two Gulf Arab states, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. Since this required the Arab leaders to ignore protests from the Palestinians, it reinforced the sense for most Israelis that the Palestinian issue was far less pressing than it had been.

President Joe Biden has reaffirmed his support for the two-state model. But his foreign policy focus has been on repairing U.S. alliances and dealing with China, not on the Middle East.

And he has been close enough to the corridors of power for long enough to know only too well how Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy has been bogged down in stalemate since the turn of the century. It has been more than two decades since President Bill Clinton tried, came close, but ultimately failed to bring a two-state deal to fruition.

That may leave Mr. Biden profoundly dubious about embarking on a new U.S. diplomatic push.

Still, the current fighting has raised another question at the heart of the Gaza paradox: whether the price of not doing so might be too high.

Parents eye another option for fall: Hybrid home schooling

With interest in hybrid home schooling on the rise, many parents are emphasizing a new priority for their children’s education: flexibility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Lines between school and home have blurred during the pandemic, including families overseeing remote public schooling or shifting to home schooling or learning pods.

Now parents are making decisions about the next school year, a task complicated by questions about remaining safety precautions come fall and, for some, the timeline for vaccines for children under 12. Parents experimenting with education options that meld learning both inside and outside the home will likely continue, observers say, as families prioritize flexibility and safety. One option more people are considering: hybrid home schooling, where students are taught at home and attend a school in-person several days a week.

“We went back and forth” about whether to go back to public school next year, says Amanda Holley, a Massachusetts mother of two girls. She decided to stick with a hybrid home schooling based on the positive experience her daughters had.

Not all families can afford home-schooling materials, or the tuition that some hybrid home-school arrangements require. And the approach can chip away at the sense of community that schools try to build, says Robert Kunzman, a professor at Indiana University.

Still, he notes, “The whole notion of what counts as home schooling is continuing to evolve.”

Parents eye another option for fall: Hybrid home schooling

Amanda Holley and her family used to enjoy walking to a nearby public elementary school. Now, a local school isn’t a part of the plan: Ms. Holley home-schools three days a week and sends her children to school elsewhere the other days.

The approach is dubbed hybrid home schooling and Ms. Holley plans to stick with it. Two days a week, she drives her daughters to Grace Preparatory Academy in Needham, Massachusetts, a 30-minute commute from their house in a suburb north of Boston. On the other days, the school provides lessons that she teaches at home.

“We went back and forth” about whether to go back to public school next year, says Ms. Holley, who works part time while her two children are at school. “But our girls have had such a positive experience, and more so than we would have expected, so we made the decision to stay.”

Lines between school and home have significantly blurred during the pandemic, including families overseeing remote public schooling or shifting to home schooling or learning pods. Parents are now making decisions about where to send their children next year, a task complicated by questions about remaining safety precautions come fall and, for some families, the timeline for vaccines for children under 12. Parents experimenting with education options that meld learning both inside and outside the home will likely continue, observers say, as families prioritize flexibility and safety.

“The whole notion of what counts as home schooling is continuing to evolve,” says Robert Kunzman, an education professor at Indiana University and managing director of the International Center for Home Education Research.

Given the involvement of parents at home this past year, he says, “it can’t help but create a greater awareness of the possibilities and the ways in which education and formal schooling isn’t limited by a building or a particular schedule necessarily. Those are things that will probably continue to resonate in our cultural conception of education moving forward.”

In a nationally representative survey of parents conducted monthly since March 2020 by Morning Consult and EdChoice – a nonprofit supporting school choice policies – parental support for some form of hybrid education after the pandemic consistently hovers around 40%, says Michael McShane, author of the book “Hybrid Homeschooling” and EdChoice’s director of national research.

Interest in home schooling also spiked in the past year. The number of students home-schooled in the United States in the 2020-21 school year climbed from an average of around 3% to just over 11%, according to a March report by the United States Census Bureau. Home-school participation rose across all racial and ethnic groups, including to more than 16% of Black households and more than 12% of Hispanic households.

Hybrid home schooling existed pre-pandemic in public and private schools, says Dr. McShane, noting that he’s seen an increase in formal hybrid home schools over the past few years and expects the pandemic to reinforce the trend.

“I think there is clearly a ton of demand for these schools. The big question is will supply rise to meet that demand,” says Mr. McShane, who supports expanding school choice options, like vouchers, to make tuition-based programs more widely available for lower-income families.

In Colorado, for example, the Department of Education lists 19 public schools and districts that already sponsor some type of in-person home-school programs. Public schools in several states receive funding from their state government for home-school students who attend one or two classes. Some traditional private schools offer home-school students the option to sign up for individual courses.

“The openness of especially public schools, and the market-awareness of private school providers, has increased in terms of seeing home-schoolers as potential educational partners,” says Professor Kunzman. While that can be a plus for schools and students, it can also chip away at the sense of community that many schools try to build, he notes.

“There are lots of benefits and values to cultivating a community of learners in a school setting and a community of school citizens, and I think it does get more complicated when you have students in a more a la carte framework, dropping in and out,” he says.

Other concerns involve the quality of home schooling and wealth disparities. In a May report by Tyton Partners, an advisory and investment firm, and the Walton Family Foundation, 55% of lower-income families who started home schooling this year are not spending any money on home schooling, while 51% of high-income families who are home schooling report spending more than $500 per month.

Growing to meet demand

Schools throughout the United States are figuring out ways to meet demand. Grace Preparatory Academy in Needham, where Ms. Holley’s girls attend several days a week, grew out of a home-school co-op formed by parents in 2012. Massachusetts considers it a tutoring service, but the school is undergoing accreditation this spring by the Texas-based nonprofit NAUMS Inc., which oversees University-Model® schools. The University-Model® network considers its schools private Christian schools. Grace Prep plans to apply with the Needham school board for private school status after it earns accreditation.

Enrollment at the school grew during the pandemic: Five families joined midyear, an anomaly in the school’s enrollment patterns. Currently, 47 students are enrolled for next year and the school is considering hiring an additional teacher for an extra classroom if more students enroll. Families are drawn to the faith-based education, and the school attracts parents who “want to homeschool ... but don’t want to do it on their own,” says Jenna Wertheimer, the school’s program director.

Tuition fees are $3,900 per student annually and the school offers financial aid. By comparison, a private school located nearby with five days of in-person schooling charges $32,950 for kindergarten and $41,275 for fifth grade. Recruiting teachers to work part time and maintaining strong communication between parents and the school are Grace Prep’s biggest challenges, Ms. Wertheimer says.

Across the country in Colorado, Mountain Phoenix Community School, a public, Waldorf-inspired charter school in Wheat Ridge, has offered a home-school enrichment program since 2013 – including Spanish, art, and orchestra. Enrollment has grown over time from a handful of students to 140 children for the 2021-22 school year. The program is expanding to a new building as a result.

“I think parents are finding that maybe their child is not excelling in a traditional public school classroom,” says Lynn Pollitt, director of the home-school program at Mountain Phoenix. “If they still don’t want their child five days a week in a brick and mortar school [they may] want the enrichment piece that the home-school program offers.”

Beyond one-size-fits-all

Families are often attracted by the flexibility that hybrid home schooling offers. Khadijah Ali-Coleman’s 18-year-old daughter was dual-enrolled and earned an associate degree at a community college while finishing high school via home schooling. Her daughter will attend a four-year university in California this fall.

“My daughter is a Black family home-schooling success story,” says Dr. Ali-Coleman of Fort Washington, Maryland, who co-founded the Black Family Homeschool Educators & Scholars group last year, and is co-author of a forthcoming book on home schooling Black children in the U.S. Dr. Ali-Coleman was able to home-school her daughter by searching out flexible work that enabled her to bring her daughter with her.

“[The book] puts to rest this myth that home-schooling parents look the same and we do all the same things. I am in a domestic partnership, but we’re not married. I’m a working mother and have been working throughout home schooling, and we’re working class, very much working class,” she says.

Back in Massachusetts, Ms. Holley says the decision to hybrid home-school her daughters means she’s had to figure out how to juggle wearing the hats of mom, teacher, and part-time professional. But she considers the extra time with her daughters and their learning rewarding.

“It’s been great to have time with them ... and see the curriculum more than I did when [my oldest daughter] was at school for seven hours a day, five days per week. It’s been really nice to be hands on and more a part of their learning experience.”

‘No longer just the white man.’ Can French literature make room for new voices?

French society is increasingly diverse, and its publishing industry is having to stretch itself to reflect this diversity in new titles and a broader literary conversation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

France’s book industry puts out around 200 new titles a day. It has thousands of publishers vying for authors and readers. But the face of French literature has long been that of a white male writer. Only 12 women writers have won the prestigious Prix Goncourt in its 118-year history.

Now a deluge of new writing is hitting the bookshelves, with titles by both established publishers and niche publishers trying to open up the field. Over the last decade, this has led to a shift in the publishing world toward greater diversity, including more titles by second-generation French authors and other writers of color.

Writing workshops are increasingly popular in France, as are graduate degrees in creative writing. The pandemic may have accelerated this shift, as more people found time to write during lockdowns.

The result is tumult and opportunity in an industry steeped in tradition that is trying to find new ways to represent the reality of its diverse society.

“There’s really a strong intention to be the most open, the most curious,” says Anne-Sophie Stefanini, the literary director at JC Lattès. “French publishing houses, big or small, are thinking about diversity right now. It’s a concern for all literary editors of this generation.”

‘No longer just the white man.’ Can French literature make room for new voices?

There’s no lighting of candles or finding that perfect spot in the house when Sandy Geronimi sits down to write. It might be when her toddler is taking a nap, or late at night when inspiration hits. But thanks to the pandemic, she’s finally devoting time to her passion.

“I’ve always liked writing, but I never did it seriously until the first lockdown,” says Ms. Geronimi, who works for France’s National Geographic Institute in Toulouse. “Until then, I never knew much about the literary world or how to write a book.”

Ms. Geronimi now follows several literary experts on social media and has submitted four short stories to national writing contests. She’s not alone: More than 5 million French people started a writing project during the country’s first lockdown, according to a May 2020 online poll.

French publishing houses have been so overwhelmed by submissions that top publisher Gallimard told the public last month to stop sending unsolicited manuscripts.

The deluge of new writing follows a decadelong shift in France’s publishing world from an elitist, male-dominated field to one of growing acceptance and diversity. Major publishers have created special collections to promote first-time authors and ethnic minorities while new publishing houses are opening the field to a larger spectrum of writers, styles, and subject matter. At the same time, self-publishing has exploded during the pandemic.

In parallel, writing workshops and graduate degrees in creative writing – once seen as a North American concept – are popping up around the country and acting as gateways to publication for burgeoning writers. Taken together, these efforts are forcing change in an industry steeped in tradition and pushing French literature to represent the reality of its diverse society.

“There is a real evolution when it comes to racial and gender diversity in French literature. The French author is no longer just the white man, over 50,” says Frédérique Anne, a French writing coach who splits her time between Paris and Normandy. “There are also more people writing for the first time who are realizing they don’t need some divine intervention to do so. The field is definitely opening up.”

A space for marginalized voices

France’s literary institutions have long struggled with a diversity problem. Though France doesn’t collect statistics on race and ethnicity, a majority of top editors and authors have historically been white. Its literary awards heavily favor men: Since France’s top literature prize, the Prix Goncourt, began in 1903, only 12 women have won.

The integration of marginalized literary voices, especially those of second-generation French or people of color, has come in fits and starts. Until the 1990s, literature written by children of immigrant parents of Maghrebis descent was categorized using a pejorative term for Arab.

The publication of a 1999 novel by Rachid Djaïdani, which described daily life in France’s housing projects where many immigrants live, was a landmark in breaking the mold. Another was the publication in 2007 of a controversial literary collection by second-generation French writers about their complex relationship with France.

But progress has been incremental. Publishers still gravitate to books by people of color from Francophone Africa or the United States, rather than minority writers who grew up in France.

“I’ve always been struck by the lack of representation in French literature of my reality: what it means to be Black in France,” says Gladys Marivat, a Paris-based literary journalist.

In 2015, she interviewed all of the major publishing houses in Paris as part of an investigation into the lack of diversity in French literature; her report went unpublished.

“When I asked [publishers] why this was the case,” says Ms. Marivat, “the answer was always the same: a total incomprehension of my question. They said, ‘But we publish authors from Francophone Africa.’ But that’s not the same thing.”

Publishers have struggled with how best to broaden their range of titles. Publisher JC Lattès uses its “La Grenade” label – created last year by acclaimed author and child of Turkish-Kurdish refugees Mahir Guven – to promote work by socioeconomic and ethnic minorities, and publishes one novel per month by a first-time author. Gallimard’s “Continent Noir” (Black Continent) collection features literature by and about Africa and its diaspora.

These imprints face competition from a new generation of publishers, like Face Cachées and Hors d’atteinte, which focus on stories about topics such as feminism, rap, or racism.

“There’s really a strong intention to be the most open, the most curious,” says Anne-Sophie Stefanini, literary director at JC Lattès and a published author. “French publishing houses, big or small, are thinking about diversity right now. It’s a concern for all literary editors of this generation.”

Niche labels find an audience

For some new or struggling writers, niche labels are preferable to well-known publishing houses. After several rejections by mainstream publishers, Bordeaux-based writer Thomas Andrew turned to Juno Publishing – which specializes in romance books – for his fantasy and LGBT romance novels.

“I was told by a few publishers that my story was good, but could I change the romance between two men to a man and a woman? I thought, no way,” says Mr. Andrew, who has published nine novels with Juno. “But publishers are not going to put money into something that strays from the norm and won’t sell.”

While France’s 10,000-odd publishers collectively put out nearly 200 books a day, some writers opt to go it alone. In 2017, one in five books printed in France was self-published, up from one in 10 in 2010, according to the French National Library.

Terence Samba, a 24-year-old writer who is Black and grew up in the Paris suburbs, self-published his first novel in December after being rejected by several publishers. “It’s a closed-off world and literary houses keep the same writers for years,” Mr. Samba complains. “Oftentimes I was asked to include a photo with my manuscript. That creates a very delicate situation.”

Part of the challenge is also encouraging marginalized French voices to write in the first place. Since 2013, the University of Paris VIII has offered one of the few graduate degrees in creative writing in the country, and aims to accept a diverse range of applicants – from newly minted graduates to midlife professionals.

And though the focus isn’t on how to crack the publishing industry, around 30 graduates have put out work since the program began, including Fatima Daas, an acclaimed French Algerian, lesbian writer who grew up in the Paris suburbs.

“Our goal is to help give permission to those who haven’t felt legitimized in the past to tell their story,” says Sylvain Pattieu, a published author who teaches within the program. “We try to give them confidence that it’s not about talent, it’s about finding their voice and perfecting their craft.”

Points of Progress

Fewer fights: Well-managed resources help keep conflict at bay

In this week’s progress roundup, careful planning for the needs of people and the natural world benefits all. One study says that armed conflicts are rare in places where natural resources are well managed.

Fewer fights: Well-managed resources help keep conflict at bay

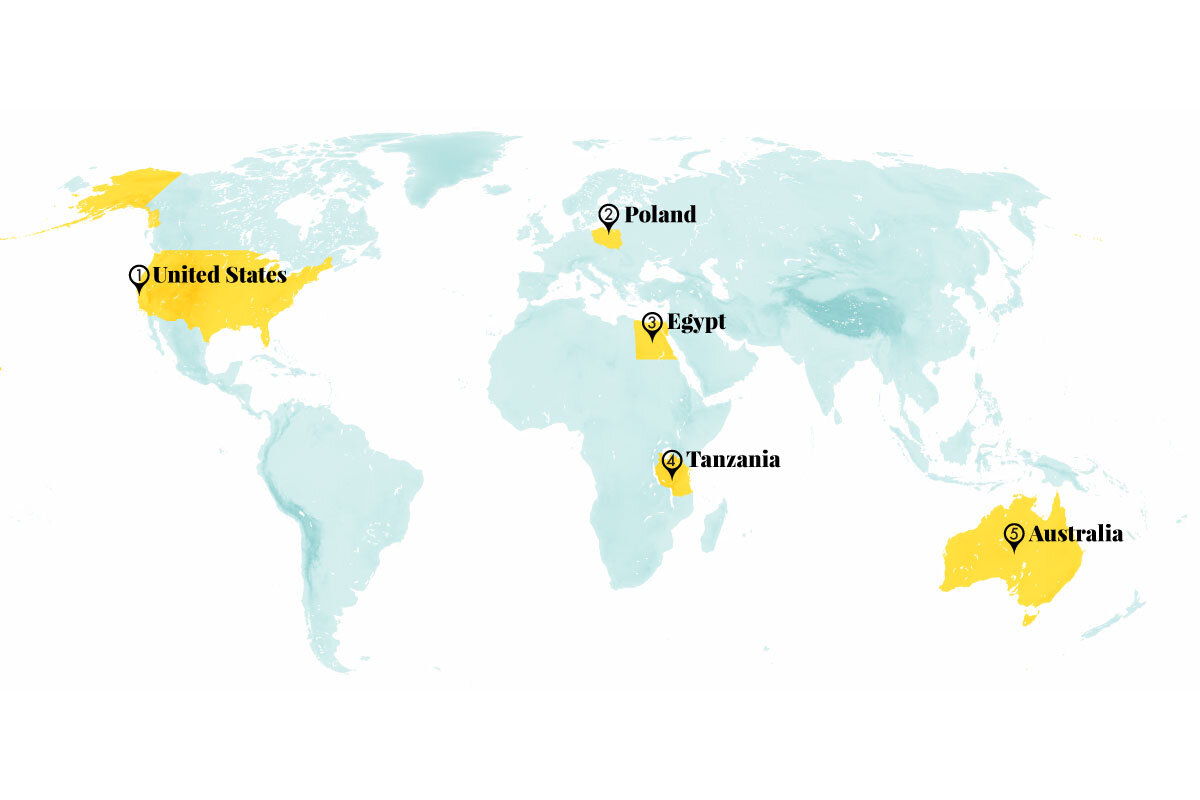

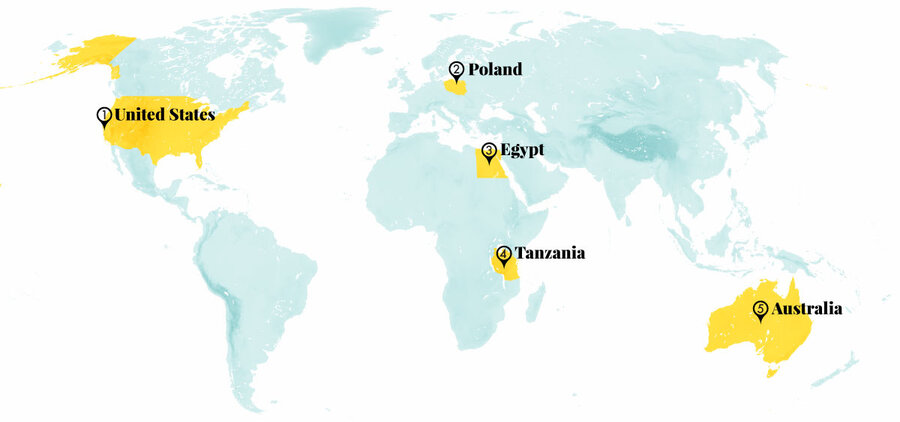

In our global wrap-up, Poland is the latest example where a rebounding apex predator species, once treated as a national pest, helps bring stability to ecosystems.

1. United States

The success of Operation Ceasefire, a community-driven effort to reduce gun-related incidents in Oakland, California, is offering other cities a holistic model for tackling violent crime. Prompted by a spike in homicides, Oakland launched its third version of a focused deterrence strategy in 2012. Under Operation Ceasefire, police meet regularly to review recent gun violence and identify individuals who are at risk of getting involved in future incidents, either as victims or as perpetrators. Community organizations provide services to candidates to change their trajectory, including one-on-one counseling from life coaches who have often overcome similar challenges. Shootings and homicides dropped every year from 2012 to 2018, even as the population in the Bay Area city grew, amounting to a 49% reduction over six years.

The program relies on city funding, as well as the participation of local churches, nonprofits, and businesses. Despite a significant crime uptick during the pandemic – when Operation Ceasefire has been unable to offer its typical face-to-face programming – criminologists still point to Oakland as an example of a sustainable crime-fighting approach that centers the community needs.

Dallas Morning News, Oakland North

2. Poland

The rebound of Poland’s wolf population is demonstrating the ecological value of large predators. Polish authorities once considered the gray wolf a national pest, and mass hunting was encouraged until the population dropped to 200 in 1975. Many factors contributed to the gradual shift from game animal to protected species in the early 1990s, including a transition to democratic government, high public trust in nongovernmental organizations, and scientific research on wolf behavior.

The roughly 2,000 wolves living in Poland today play a critical role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. Packs frequently prey on beavers (which can cause expensive environmental damage) and deer, helping control herbivore populations so forests have a chance to regenerate. The remains from wolf prey also feed other species, including bears and lynxes. With 30% of Poland’s wolf population considered transnational – meaning packs travel to adjacent countries, bringing much-needed genetic diversity to other rebounding populations – conservationists say the continued growth and monitoring of Poland’s gray wolf population are important for all of Europe.

Tygodnik Powszechny, International Wolf Center

3. Egypt

Egyptian lawmakers have approved tougher sentences for female genital mutilation, in an ongoing effort to end the practice. Although banned, FGM persists throughout the country because of deeply entrenched beliefs and lack of enforcement. In 2016, a United Nations survey found nearly 90% of Egyptian women and girls between 15 and 49 have undergone FGM. Under the new penalties, medical professionals – who still market FGM services publicly, activists say – can face five to 20 years’ imprisonment for performing the procedure, up from the previous seven-year maximum, and may be barred from practicing for up to five years. Family members who request the procedure can also face prison time.

Advocates say that seeing the strengthened legislation in action is what will make the difference. “It is a good step,” said Entessar El-Saeed, director of the Cairo Foundation for Development and Law. “We are still struggling with a deeply-rooted concept in the Egyptian society and even among some doctors and judges that FGM is not [a] crime.”

Thomson Reuters Foundation

4. Tanzania

Tanzania has welcomed its first female president. In March, then-Vice President Samia Suluhu Hassan was sworn into office after the death of President John Magufuli. Since taking office, she has made several changes, including refocusing Tanzania’s COVID-19 strategy – her predecessor had been one of Africa’s most prominent coronavirus skeptics – and restoring press freedoms.

Press freedom had plummeted under President Magufuli’s administration, according to rights groups, with authorities arresting prominent journalists and revoking media licenses. Last year, the Committee to Protect Journalists said the government had silenced at least four publications since March 2019, including the opposition-leaning paper Tanzania Daima. President Hassan has given orders that these outlets may reopen. “We should not give them room to say we are shrinking press freedom,” she told officials in April. “We should not ban the media by force. Reopen them, and we should ensure they follow the rules.” Some activists applauded the directive, but urged repeal of repressive laws.

Voice of America, Reuters, Al Jazeera

5. Australia

The Australian government has committed $100 million (Australian; U.S.$77 million) to improve the well-being of ocean areas. With roughly 85% of Australians living within 30 miles of a coast, officials say the country is economically and environmentally tied to the oceans. The new funding package includes nearly A$40 million for improving management of Australia’s marine parks and A$30.6 million for coastal ecosystem restoration projects that target “blue carbon” species such as mangroves and sea grasses, which play an important role in absorbing carbon from the atmosphere. Other funds will go toward protecting iconic marine species and expanding nine Indigenous protected areas to give communities more autonomy over marine resources.

“Protecting our oceans must be a top priority for all Australian governments,” said Darren Kindleysides, CEO of the Australian Marine Conservation Society. “This funding commitment is a vital and promising package of measures to address some key threats, such as the loss and degradation of coastal habitat and capture of wildlife in commercial fishing nets.”

Canberra Weekly, Australian Government

World

Defending nature can reduce the risk of armed conflict, according to a new report. In analyzing more than 85,000 conflicts from the past 30 years, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found that violence rarely broke out in protected areas, including national parks and wildernesses. Although such areas make up an estimated 15% of the world’s land, only 3% of conflicts occurred within their boundaries.

The report offers evidence that conservation and sustainable land management are important tools not only to fight climate change, but also to secure peace. Experts from the IUCN say this is in part because natural resource scarcity can exacerbate tensions. The organization recommends the international community establish explicit protections for park and wilderness staff, and call for sanctions against those who commit environmental war crimes.

Thomson Reuters Foundation, International Union for Conservation of Nature

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why so many Colombians are protesting so long

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Anti-government protests in Colombia have now entered their fourth week, which is unusual enough for one of Latin America’s stronger democracies. The numbers are also atypically big, with tens of thousands on the streets at a time in most cities. Another notable is the range of voices, from urban youth to rural poor. And the number of their complaints spans from corruption to police brutality to a proposed tax hike that first triggered the protests.

Most remarkable, however, may be a popular demand for the new style of politics.

“What seems to be ruled out is the continuity of the politics of hatred and polarization that have characterized Colombia in the past several years,” writes Mauricio Cárdenas, a former finance minister, in Americas Quarterly. “Governing from one side of the political spectrum is a recipe for disaster.”

Now, protester Miguel Morales told BBC, “We need to make good choices in next year’s election.” By the size and duration of the protests, the choice seems to have been made.

Why so many Colombians are protesting so long

Anti-government protests in Colombia have now entered their fourth week, which is unusual enough for one of Latin America’s stronger democracies. The numbers are also atypically big, with tens of thousands on the streets at a time in most cities. Another notable is the range of voices, from urban youth to rural poor. And the number of their complaints spans from corruption to police brutality to a proposed tax hike that first triggered the protests.

Most remarkable, however, may be a popular demand for the new style of politics.

“What seems to be ruled out is the continuity of the politics of hatred and polarization that have characterized Colombia in the past several years,” writes Mauricio Cárdenas, a former finance minister, in Americas Quarterly. “Governing from one side of the political spectrum is a recipe for disaster.”

Colombians see a disconnect between their daily problems and politics marked by divisiveness and acrimony. “They are telling the traditional politicians that they are ready to replace them in order to make the country more democratic, less corrupt, less unequal,” states Mr. Cárdenas.

Before the protests began April 28, many people already had high expectations of political reconciliation. In 2016, the government entered a peace pact with the country’s largest rebel group, the FARC, or Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. The agreement promised to bring the rebels into politics and end a half-century of war. But slow implementation of the pact is now one of the protesters’ grievances.

With elections due in 2022, public opinion has shifted against the conservative president, Iván Duque. He is trying to reach out to youth but his popularity has only fallen. “We are looking at a citizenship that is more committed and involved,” said political analyst Laura Gil in a YouTube forum.

Among Latin American countries, Colombia ranks relatively high in its capability to combat the No. 1 complaint of the protesters – corruption. It has a high level of civil society, investigative journalism, and education, according to Transparency International. Now, protester Miguel Morales told BBC, “We need to make good choices in next year’s election.” By the size and duration of the protests, the choice seems to have been made.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Turn to Love’s parenting

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Larissa Snorek

Turning to God, divine Love, for inspiration and guidance brings greater wisdom, peace, and joy to parenting efforts.

Turn to Love’s parenting

Things in our house kept going missing. It was stressful. One day, when there was yet another item that couldn’t be located, my six-year-old daughter turned to me and, almost too quietly to hear, said, “Mom, have you asked ... God?” And then she ran off.

It stopped me in my tracks. Had I turned to God? Or was I running myself ragged trying to keep it all together? As I got quiet, considering this, I suddenly knew where the needed item was.

It was such a tiny moment, but it has reminded me again and again of how different the awesome responsibility of parenting can feel depending on whether we’re trying to do it through our own frenetic efforts or through a moment-by-moment trust in infinite Love, God. To turn toward Love is to see that “the kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17:21). This kingdom is felt in “unselfishness, goodness, mercy, justice, health, holiness, love” reigning within us, within our consciousness, as the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, explains (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 248).

From that perspective, being a mom or dad is more about having the privilege of seeing our Father-Mother God express Her care for our children through us than about feeling pressure from that too-common belief that our kids’ success depends entirely on how we perform as parents. That can feel crushing.

The fact is, the spiritual qualities God expresses in parents and children are the core of our being – we’re not products of beliefs or behavior patterns conditioned in us from childhood. Forming models in thought on the basis of the qualities of the kingdom of heaven sets a foundation for positive parenting, and we don’t feel at the mercy of our upbringing, of struggles or stress, or of others.

While the fear of not doing the right thing for our kids can loom large at times, pausing to understand our true relation to God conquers fear. I know I mother best when I’m clear how I’m being mothered by God. Understanding cause and effect as originating in God alone, we all can get clearer, higher views of ourselves and our kids and express our authentic, spiritual selves, which are not subject to human history. Doing the right thing comes from being the divine expression we are perfectly designed to be. Divine power rectifies past mistakes and gives us a present awareness of God’s care for everyone.

When we feel divine Love loving us, this love overflows to our kids. Hymn 139 in the “Christian Science Hymnal” includes this line: “Give of your heart’s rich overflow” (Minny M. H. Ayers). Securing our own sense of being parented by God gives us an unshakable sense of satisfaction and approval, so we don’t feel the need to get these things from others and their response to us. Pausing to turn to Love helps us to not live in reaction to our kids, or to anyone else.

It’s a trap that when our kids are successful, we feel good, and when they mess up, we feel terrible. It can leave us feeling that our happiness is at the mercy of their successes or failures. Yet divine Love’s compassion keeps us from getting pulled into drama or feeling that our mood is tied to others’ behaviors and actions. How crucial it can be during demanding “mom (or dad) moments” to take a step back mentally and remember that our children are not a task to accomplish but a blessing to be grateful for. It helps us stop trying to calm the situation and lets Christ, the true idea of God, calm us. And as a result, the whole situation settles into the harmony of divine power over all.

To know that we live wholly in Spirit, God, is to see an underlying spiritual purpose in everything. It helps us frame our experience in families as a time of deepening our understanding and experience of Love and its expression. Love’s care and guidance never leave us. The light of divine Love lets us embrace the adventure and joy of parenting rather than agreeing to being run ragged. Turning to God, pausing in the midst of daily demands – or even upheaval – we can appreciate the childlikeness in our kids and ourselves and let it teach us of its beauty and wonder.

Originally published as an editorial in the May 3, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

After the storm

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when chief culture writer Stephen Humphries interviews an author who believes no conflict is unsolvable, for the next installment of The Respect Project.