- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The holidays’ gift to us

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

To call the past few years a time of upheaval is a pretty huge understatement. Now we’re witnessing what economists are calling the Great Resignation, the unprecedented decision by many Americans to voluntarily quit their jobs and ask what they really want from life.

In some ways, this time of year is about doing just that. Yes, there are big meals and presents and holiday music. But amid all that is time for reflection on what really matters.

Which raises the question: Given all we have been through – what we have learned about the preciousness of life, the amazing diversity of our humanity, the fleeting joys and persistent struggles – is it possible that we are essentially renovating our societies?

Renovations take no small amount of scaffolding and disruption. The Great Resignation might also be called the Great Reconsideration. Our expectations are changing, recalibrating along higher hopes for equality and fairness, compassion and safety, freedom and responsibility. Those are some big-ticket items. They might require punching through a few walls or some rewiring. But even amid the dust, this season shows us glimpses of what might come.

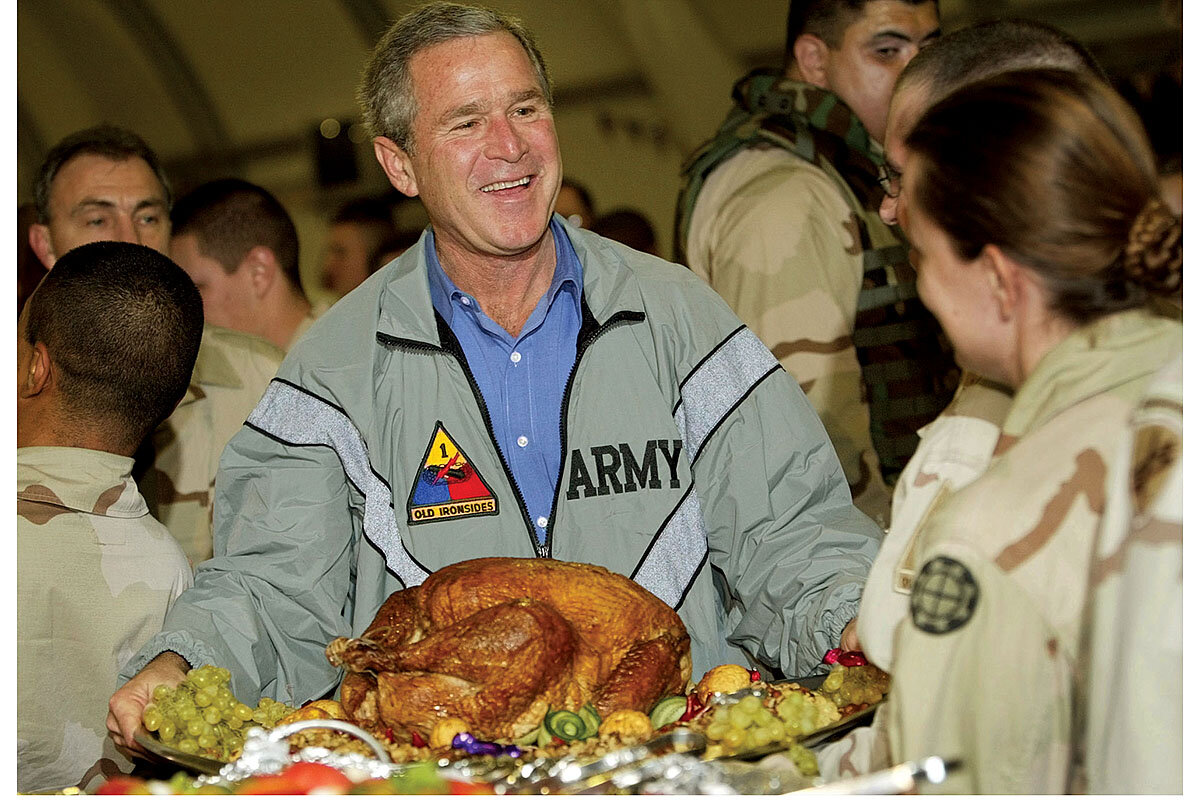

Maybe the lesson of any of our seasonal holidays is exactly what all the Hallmark cards say it is – that gratitude and goodwill and grace do matter, and that taking time to reorient our lives around them renews us. So this Thanksgiving, whether we’re at home or eating a meal with thousands of friends at Fort Bragg, it’s worth considering that the renovations we most need are the very things we are now pausing to celebrate.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Cooking for 15,000: How Fort Bragg pulls off Thanksgiving

A Thanksgiving meal is a way for U.S. troops to feel at home while serving far away. To many, it’s also a moment to express their gratitude to each other, their country, and those who died defending it, not to mention to get some good chow.

How do you feed 15,000 people for Thanksgiving?

Assembling the menu at Fort Bragg – the U.S. military’s largest base by population in the world – is a finely tuned test of logistics. Sourcing starts a year ahead of time, advancing in complexity as hogs are thrown over the fire the night before and turkeys go into ovens the morning of the feast.

This year, chef Princido Texidor’s spreadsheets include 50 whole turkeys, 2,000 pounds of boneless turkey breast, 1,000 pounds of steamship round beef (a prime hindquarter cut), 1,500 pounds of fish and shrimp, 1,500 pounds of ham, and 5 whole roasted hogs, plus towers of sweet potato pie and other sides.

As families across the United States know, though, Thanksgiving is about more than just the meal. It’s about ritual, and coming together; it’s one of two special meals the military provides to its war fighters each year, including Christmas.

“I can’t even tell you how important [Thanksgiving dinner] is for morale,” says resident hog smoking expert Sgt. Robert Moses.

And Fort Bragg’s Thanksgiving isn’t just a one-off event – it’s the culmination of Mr. Texidor’s lifelong quest to transform the military’s food culture from mess hall “slop” to something more sophisticated.

“When it comes to Thanksgiving,” he says, “everything that [the Army cooks] have gone through to get here, they get to showcase.”

Cooking for 15,000: How Fort Bragg pulls off Thanksgiving

Princido “Tex” Texidor knew deep in his teenage heart that the El Conquistador wasn’t for him. The restaurant in the Puerto Rican town of Arecibo commanded nearly all his father’s time, and Mr. Texidor wanted no part of that.

But when he sat down with an Army recruiter in San Juan to discuss his future, the options felt uninspiring. “‘Artillery, tanks, infantry,’ the guy kept saying,” Mr. Texidor recalls. The young recruit consciously avoided one other category, until he finally had to choose. Then he gave in: “Food service” it was, he says.

As he waded into the Army’s mess hall bureaucracy, Mr. Texidor – whose boxer’s build is offset by a soft voice – realized he couldn’t quite shake El Conquistador, after all. Through more than three decades in the armed services, Mr. Texidor rose to eventually serve for three years as the Army’s chief food adviser during some of the military’s most active years in Afghanistan and the Middle East. According to cooks and culinary management specialists at Fort Bragg, Mr. Texidor’s sourcing, adaptability, and restaurant-rooted guidance helped the Army transform its food culture, refining what soldiers had long known as “slop” to more sophisticated cuisine, such as racks of ribs for a Thursday lunch at the 3rd Brigade Warrior Restaurant here on the base.

Mr. Texidor sees the accomplishments as a reflection of what he learned from his late father: a mix of dedication, hard work, adaptability to challenges, and an embrace of tradition. And on Thanksgiving, that experience will culminate in what is likely the world’s biggest Thanksgiving feast: As many as 15,000 people are expected to sit down at Fort Bragg’s dining halls and express their gratitude to one another, their country, and those who perished defending it – and eat.

“Thanksgiving defines what I do, why I’m here,” says Mr. Texidor in an interview at a warrior restaurant on the base a few weeks before Thanksgiving. “It means everything.”

Aided by a platoon of cooks and supervisors, Mr. Texidor is in no small part responsible for making sure the “hot chow” is sourced and served at 12 dining facilities on Fort Bragg – the U.S. military’s largest base by population in the world – on the day they celebrate Thanksgiving here, which this year is Nov. 23. (They mark the holiday on an alternative day so cooks on the base can spend Thanksgiving Day with their friends or families.) The meals will be expectantly watched over by everyone from three-star generals to silver-haired veterans, from soldier moms to Green Berets. It will be replete with ice sculptures and decorations, all happening amid global supply chain problems that have had Army cooks squirreling away canned sweet potatoes for a year.

For Mr. Texidor and the base mess sergeants, the pressure is also on to make up for a pandemic-crimped celebration last year, when cooks somehow still managed to put together thousands of takeout meals amid COVID-19 outbreaks and facility closures.

This year, the Fort Bragg feast, Mr. Texidor’s spreadsheets conclude, includes 50 whole turkeys, 2,000 pounds of boneless turkey breast, 1,000 pounds of steamship round beef (a prime hindquarter cut), 1,500 pounds of fish and shrimp, 1,500 pounds of ham, and 5 whole roasted hogs, plus towers of sweet potato pie and other sides.

“Thanksgiving is our Super Bowl,” he says. “And we can’t lose.”

The logistics required to bring food to soldiers on the front lines of a conflict represent what the late military historian James Huston called “the sinews of war.”

Soldiers have always relied on their stomachs as much as their military cunning in times of conquest. Roman armies, for instance, often pillaged their way to domination, confiscating food as they captured territory, carrying salt with them to season the spoils of war.

By the Middle Ages, the English had begun to hone how troops are supplied. A thousand years ago, in the days of William the Conqueror, the daily requirement for 14,000 troops on the march was 28 tons of wheat flour.

Today, the U.S. Army lists subsistence, or food and water, as a “Class I” requirement. Unlike guns or vehicles, food needs to be resupplied constantly, which adds to the logistical complexity. In a way, that makes Mr. Texidor’s Thanksgiving, and the meals prepared by U.S. military cooks around the world, one of the most critical tasks in America’s $700 billion yearly effort “to deter adversaries and defend the United States homeland and its citizens,” as the undersecretary of defense wrote in the 2021 Defense Budget Overview.

Fortunately, Mr. Texidor will have some help with the turkey.

For 50 years, the U.S. Defense Logistics Agency has fulfilled orders from military cooks. It’s a byzantine task that peaks on Thanksgiving. Whether it’s the 127 U.S. troops stationed in Canada, the 381 troops in Saudi Arabia, or the 52,280 troops here at Fort Bragg, the Army extends to every war fighter two special holiday meals – Thanksgiving and Christmas. Those meals represent a powerful ritual for a volunteer force. They are also a mean feat to pull off, given that the U.S. military operates some 750 bases in 80 countries.

Indeed, consider the culinary challenge at Fort Bragg alone. Nestled amid the southern yellow pine of central North Carolina, the base is a sizable city in its own right: 270,000 people spread across 500 square miles. Most of the people on base will celebrate Thanksgiving in their homes. But about 15,000 will visit one of the many dining halls for their drumsticks and stuffing on Nov. 23.

Robin Whaley, for one, thrives on making sure every base will have enough food. From a computer adorned with pictures of troops enjoying Thanksgiving feasts, Ms. Whaley, a 33-year logistics veteran, helps lead 300 specialists tasked with sourcing, procuring, packaging, and delivering nearly 10,000 turkeys around the world. Her unit is headquartered in Philadelphia.

Hundreds of thousands of orders go out to prime suppliers – companies like Smithfield Foods and US Foods – and those orders are tracked to warehouses. That is a complicated task made particularly difficult this year by the supply chain issues that have gummed up the logistics agency’s work, as well as the U.S. economy.

But preparation is a hallmark of the military. Turkeys aren’t any different. While millions of Americans scour aisles for yams and plump birds in the final weeks before the holidays, Ms. Whaley begins placing orders in March. As those shopping lists are filled, her staff monitors the orders’ movement from the poultry farms to regional storage centers. There are weekly “holiday tracker meetings” to address problems.

Individual dining facility managers then place the orders that bring the food on trucks and planes, and at times on pack mules, to their mess hall refrigerators. Staff Sgt. Jamie Contreras, one of the cooks at Fort Bragg, says his preparations for Thanksgiving start nearly a year in advance, when space in the storage rooms allows the staff to start gradually restocking.

“For me, the preparations start as soon as the holidays are done,” says Sergeant Contreras. “You start building your pantry right away until you have a robust menu.”

Inevitably, though, hiccups arise with deliveries – and sometimes take unusual ingenuity to resolve. One civilian kitchen supervisor at Fort Bragg recalls during a stint in Afghanistan that a nongovernmental organization helped him source several whole hogs in time for Thanksgiving – not an easy task in a Muslim country where most people don’t eat pork.

“While soldiers are deployed away from their homes and families, knowing that they can celebrate such a familiar holiday or meal is critical,” says Ms. Whaley of the Defense Logistics Agency’s subsistence unit. “Food is emotional, and just having that meal that you’re familiar with – that mac and cheese, that ham, that stuffing – all of those comforts of home give a little more comfort while they’re away. Also, a lot of war fighters who are stationed away don’t have the convenience of going to the supermarket, so we have to make sure they have everything they need – down to the butter.”

Then comes the actual cooking itself. Mr. Texidor – now a civilian contractor whose experience the Army leadership leans on to help guide the preparations – says the kitchens at Fort Bragg start humming 14 hours in advance, and everything is done according to procedures fine-tuned by each dining facility.

The hogs go on the fire the evening before to cook through the night, watched over by resident smoker expert Sgt. Robert Moses. Last year, he helped roast three whole hogs for the 82nd Airborne. “I can’t even tell you how important [Thanksgiving dinner] is for morale,” says Sergeant Moses.

The turkeys are slipped into massive ovens in the morning, along with the steamship beef. Stuffing, gravy, and mashed potatoes are prepared on precise schedules in bins and bowls the size of small bathtubs.

“It’s all industrial, things you might find in a cruise ship or major hotel, designed for mass feedings,” says Mr. Texidor. “It’s crowded, and we have different teams preparing meats, starches and veggies, and salad. It’s a team concept where you have three or four cooks per team to ensure that everything is set up right and in a timely manner.”

The process “is pretty rough” for the cooks, says Sgt. Maj. John-Joseph Williams, a longtime member of the Army who has cooked for the Joint Chiefs of Staff and served as a personal aide to a three-star general.

Each facility sets its own decorations, which are judged by military higher-ups, and the cooks summon their inner Gordon Ramsay on presentation. The steamship rounds are laid out to carve alongside hazelnut-brown roasted turkeys.

“The serving line is slower because obviously [celebrants] are trying to admire what’s on the line, because everything is decorated and garnished and looks so good and delicious, so everybody is eating with their eyes first,” says Mr. Texidor. “It’s open seating. You sit wherever you want to and just enjoy the company of everybody there. A lot of times command generals or sergeant majors will go through the dining room and greet people. It’s a very family atmosphere.”

Mr. Texidor acts as chief inspector. He goes around to all the facilities on Thanksgiving Day, doing spot-checks, making sure the kitchens are clean and the food is being prepared correctly – and on time.

He doesn’t mind being in a kitchen when everyone else is celebrating. It’s what he did growing up.

“My family, we all worked in the restaurant, and we used to sell the Thanksgiving dinner, so we spent Thanksgiving at the restaurant,” he says. “That’s always part of you, regardless of where you go.”

The care that goes into preparing the Thanksgiving meal at Fort Bragg shows how food service has evolved in the military. It’s what Mr. Texidor calls a shift to a more “culinarian” outlook.

In the old days, soldiers ate in a mess hall. Those long ago were replaced by “d-facs” – dining facilities. Now troops eat at “warrior restaurants.”

Mr. Texidor says part of the transition is simply understanding the power of “lickies and chewies” – little gifts and treats that can elevate a meal, even ones as mundane as MREs, or meals ready to eat, that soldiers consume in the field.

Mr. Texidor served under Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, who took command of a lawless New Orleans in the days after Hurricane Katrina. He watched as the general worked to change the food culture at Fort Bragg.

“General Honoré looked around at all the ... restaurants on the base and said we should be serving food that competes,” says Mr. Texidor. “Soldiers shouldn’t have to pay for good food.”

To hone their skills in the new culinary environment, the cooks here and on other military bases periodically take part in competitions as part of their training. One was held in late October at Fort Bragg’s Joint Culinary Center, featuring the best cooks on base.

Styled on the Food Network’s cooking show “Chopped,” the contest involved giving each contestant a mystery basket of several food items, from which they had to prepare a meal in a set amount of time.

Unlike on TV, however, the cooks weren’t judged just on presentation, creativity, and taste. This being the military, they were also evaluated on their personal appearance, down to whether their fingernails were clean and undershirts properly tucked.

Even after struggling through the inspection portion – he forgot to wear an undershirt, among other dings – Sgt. Taehoon Yoon won with a dish of sweet-and-sour pork. His prize: a spot on the base’s competitive culinary team, which goes up against other bases, and a tandem skydive with the Golden Knights, the Army’s aerial parachute demonstration team.

“When it comes to Thanksgiving, everything that [the Army cooks] have gone through to get here, they get to showcase,” says Mr. Texidor.

For one of the food service supervisors at Fort Bragg, preparing the Thanksgiving meal is important for reasons that go beyond simply duty. It carries personal meaning. He’s been out in the field during the holiday and knows, like many career soldiers, what the sight of a drumstick can evoke in a time of war.

A decade ago, Sgt. 1st Class Richard Honrine was stationed with 24 other soldiers in a far-flung mountain redoubt in Afghanistan. On Thanksgiving Day, he heard a faint chop-chop of rotors. A quick drop of mermites, or packing boxes, meant a fried turkey dinner for him and his mates. (Yes, the Army supplies small portable fryers in those kits.)

“It meant the world to us – it was such a connection,” says Sergeant Honrine. “I’ll never forget it.”

Mr. Texidor personally carried such meals on helicopters at one point in his career. “For a soldier to know that the Army has food for us regardless of where we may be, and that we can get almost any type of food to them, is a big deal,” he says.

As he eagerly awaits Thanksgiving at Fort Bragg, Army Spc. Austin Watz, from Great Falls, Montana, fully agrees. He is dipping into some well-sauced pork ribs at the 3rd Brigade’s Warrior Restaurant.

Specialist Watz looks forward, in particular, to having three- and four-star generals take turns serving food to soldiers – a

measure of thanks in a gravy pour.

He likes the camaraderie that pervades the cafeterias at the holidays, too. Thousands of war veterans who have settled in the area come back on base to sit next to young men and women fresh from basic training. Gold Star mothers and fathers sit shoulder to shoulder with company commanders.

“It is a time for us to be treated like individuals,” says Specialist Watz. “Thanksgiving, for a lot of us who are far from home, is our most challenging time of the year. So getting a Thanksgiving meal really helps. It’s a reminder that this is our second family.”

The Explainer

Thanksgiving in a can? The holiday’s edible controversies explained.

Underneath the annual culinary boasting about the best – and worst – Thanksgiving dishes lies something deeper: decoding traditions, both familial and historical.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Does cranberry sauce count if it comes from the can? Have you ever actually eaten a yam, or are you really eating a sweet potato? And don’t even start with green bean casserole.

For every “classic” Thanksgiving dish, there are ardent defenders and detractors in the never-ending debate about what belongs on the holiday table.

This culinary smack talk is actually a form of cultural coding, finding your “team,” so to speak. Somewhere someone taught you that your kin prefer this over that and you have stuck to it ever since. But where do these Thanksgiving traditions come from anyway?

Diving into those questions reveals more than just gastronomical preferences – it helps us sort out our own family traditions. It also reveals slices of American history, from the 30 years of research it took to develop canned cranberry sauce to the links between yams, sweet potatoes, and the transatlantic slave trade.

Besides, historians have long (and patiently) explained that we don’t really know what the Pilgrims and Wampanoags ate during their diplomatic talks at the so-called first Thanksgiving 400 years ago. So that means we all have had ample room to make up and defend our own traditions.

Thanksgiving in a can? The holiday’s edible controversies explained.

Thanksgiving is a time of assembling family and friends and reengaging in age-old debates over what really belongs on the holiday table. This culinary smack talk is actually a form of cultural coding, finding your “team,” so to speak. Somewhere someone taught you that your kin prefer this over that and you have stuck to it ever since. But where do these Thanksgiving traditions come from anyway?

Historians have long (and patiently) explained that we don’t really know what the Pilgrims and Wampanoags ate during their diplomatic talks at the so-called first Thanksgiving 400 years ago. So that means we all have had ample room to make up and defend our own traditions.

Here is a brief look at the controversial histories of some “classic” dishes.

Does canned cranberry sauce count?

However you prefer your cranberries – as a mold with ridges, sweetened with maple syrup, juiced up with an entire orange, or with a bit of fire from diced jalapeño – this indigenous fruit is truly North American.

Let’s get this other fact out of the way. Many, many Americans love jellied cranberry sauce from the can. It was Marcus Urann, a lawyer turned farmer, who saw an opportunity to lengthen the fleeting cranberry season through industrial canning in 1912. He developed his science over three decades, culminating in the launch of the Ocean Spray cranberry sauce log in 1941. Today, Ocean Spray claims Americans consume 400 million pounds of cranberries yearly, glugging down 5,062,500 gallons of jellied cranberry sauce every holiday season.

It’s hard to argue with those numbers, but traditionalists still line up behind cranberry sauce freshly made on the stove-top. Amelia Simmons, after all, mentions cranberry sauce as a nice side to roasted turkey in American Cookery in 1796. One piquant step further is cranberry relish – raw ingredients blended together for a fresh, tart sweep of the tongue in the middle of the typically heavy Thanksgiving dishes.

Are those really yams?

Glazed sweet potatoes, also known as “candied yams,” is a simple dish with linguistic complexity baked into it. Sweet potatoes, indigenous to Central and South America, are tuberous roots and taste like carrots. Yams, with their dark, rough skin and white, orange, or purple starchy flesh, belong to a different botanical family entirely and are indigenous to Africa and Asia. Enslaved West African people arriving in the New World took to sweet potatoes as a reminder of home, even calling them after the African nyamis, which was shortened to yams. Southern growers adopted the word yam to distinguish their crop from the paler Northern variety. But it is highly unlikely you’ve actually bought and prepared a true yam in the United States unless you shop at specialty markets.

Glazed sweet potatoes may have a mid-century ring to it, but the dish more likely dates from at least the middle of the 19th century. A recipe for it was included in Fannie Farmer’s 1896 Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. By 1919, a booklet from the Barrett Company on Sweet Potato and Yams included the line, “A few marshmallows may be added a few minutes before removing from oven.” What enterprising domestic economist in a test kitchen added this confectionary flair that had this dish passing as a “vegetable”? The credit remains unclaimed.

Green bean casserole ... why?

Things can get confusing in the swirl of a test kitchen, as Campbell’s Dorcas Reilly recalled in a 2001 interview with The Boston Globe. Trying to figure out how to boost the sales of cream of mushroom soup, Ms. Reilly’s team of test cooks created a side dish with common pantry staples: milk, soy sauce, green beans, fried onions, and mushroom soup. The result was a recipe so simple and palate pleasing with its fat and salt content that even clumsy and harried cooks could master it in 10 minutes. But the time and place of the eureka moment remained elusive even to the kitchen manager.

“It’s hard to be specific, because it happened 46 years ago,” Ms. Reilly recalled in 2001. “We know that it first appeared in an [Associated Press] story in 1955.” From there it somehow captured American hearts.

Ms. Reilly donated the original green bean casserole recipe to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2002, but remained reluctant to take the credit. Her obituaries in 2018, however, hailed her as the recipe’s creator.

Like most cherished Thanksgiving recipes, she said it was a team effort.

Early settlers loved the pumpkin. But it was Mexico’s favorite first.

Americans have time-honored traditions around Thanksgiving, but new backstories are coming to light. The pumpkin, for example, offers a lesson in cross-cultural cooking.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Four hundred years after the first Thanksgiving, the pumpkin pie still reigns supreme atop many dinner tables across the United States. But how did the humble pumpkin – usually overshadowed by its regular companions of sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and cloves – secure such a hallowed role?

One clue is to look south. Pumpkin – and all its varieties – is indigenous to Central and South America. Mexican cooking, for example, incorporates both sweet and savory uses for the entire pumpkin plant.

Historians are reluctant to describe what was on the menu in 1621 when the Pilgrims and Wampanoags had their diplomatic talks – nobody really knows – but according to the Plimoth Patuxet Museums in Plymouth, Massachusetts, stewed pumpkin was “an ancient New England dish.” When you compare recipes, it doesn’t sound all that different from calabaza en tacha, or candied pumpkin (see recipe below), a traditional dish for Día de Muertos, an autumn Mexican holiday that honors loved ones who have died.

As for how the humble pumpkin got from Mexico to New England in the first place? Did Mexicans somehow swap recipes with settling Pilgrims by way of Indigenous tribes? It’s an agricultural mystery. But there appears to be some universal agreement through the centuries and across geopolitical borders that pumpkins could use a little sugar and spice.

Early settlers loved the pumpkin. But it was Mexico’s favorite first.

It’s been 400 years since the recently arrived Pilgrims and resident Wampanoags held a three-day diplomatic feast that historians later described as the first Thanksgiving. And it’s been 200 years since Sarah Josepha Hale, an early arbiter of good American taste, suggested in a novel that a turkey should fill the meal’s centerpiece, with pumpkin pie occupying “the most distinguished niche.”

But how exactly did the humble pumpkin – a stringy squash generally overshadowed by its regular companions of sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and cloves – come to secure such a hallowed role in the most American of holidays? What does the pumpkin’s appearance on tables across the United States each November say about cross-cultural traditions?

The answers may lie not along the shores of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, but much farther south – in Mexico. “In our culture, nothing goes to waste from the pumpkin plant,” says Mely Martínez, author of the cookbook “The Mexican Home Kitchen,” from her home in Frisco, Texas. “I am from Tampico [on Mexico’s Gulf Coast], and there have been discoveries in caves there by archaeologists who found pumpkin seeds from 10,000 years ago.”

Pumpkin – and all its varieties – is indigenous to Central and South America. Mexican cooking, for example, incorporates both sweet and savory uses for the entire pumpkin plant, says Ms. Martínez. The tender leaves are used in soups, and the flesh is used as filling in everything from tamales to empanadas to tortillas. Even the pumpkin seeds are boiled or roasted, coated with sugar or salt and eaten as a snack, ground into a paste for green moles, or rolled out into a sweet nougat for candies.

Mexican pumpkins, broadly known as calabaza de castilla, have a darker and thicker skin than the bright-orange sugar pumpkins popular in the U.S. Calabaza (Spanish for pumpkin) was discovered by Spanish conquerors, goes one theory, who took samples home to Queen Isabella of Castile in the late 1400s along with gold and other riches. She gave it the royal nod of approval, thus calabaza de castilla, says Ms. Martínez.

But the Spaniards were not the only ones intrigued by this round ambassador from the New World. When interacting with Indigenous peoples, the English also encountered pumpkins – they carried samples back to the motherland, and borrowed the French term for the squash when they started writing about “pompions” in cookery books in the 1600s.

“You don’t see pumpkin pies turn up [in cookbooks] until about the 1650s,” says Kathy Rudder, curator of craft and reproduction artifacts at Plimoth Patuxet Museums in Plymouth, Massachusetts. “In fact, even one of those recipes is actually taking the pumpkin and hollowing it out, filling it with a milky custard, baking it, and using the pumpkin [skin] as a crust.”

Settlers sang their gratitude for the fortitude of the squat produce when wheat was reluctant to grow in the stony fields of New England. Part of a stanza in the “Forefathers’ Song” of 1630 goes, “Instead of pottage and puddings and custards and pies, / Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies; / We have pumpkins at morning and pumpkins at noon, / If it was not for pumpkins we should be undone!”

The Plimoth Patuxet Museums (formerly Plimoth Plantation) is honoring the 400th anniversary of the first Thanksgiving with an exhibit – “We Gather Together: Thanksgiving, Gratitude, and the Making of an American Holiday” – that traces the diplomatic purposes of the meal through the centuries and includes a timeline of tables punctuated with place settings featuring notable dinners throughout history.

“What we are showing on the tables is something called stewed pompion, which is first written down in 1672 by John Josselyn,” says Ms. Rudder, who keeps a binder full of historic pumpkin references. “He calls stewed pompion ‘the ancient New England standing dish,’ ... [meaning it’s] something that’s on the table all the time.”

The English, who put everything in pies, began experimenting with apples and pumpkins. In 1796 Amelia Simmons described the recognizable Thanksgiving pumpkin pie in what is largely considered to be the first American cookbook, “American Cookery.” But that doesn’t mean the pumpkin pie was a new invention. Recipes in cookbooks tend to follow the times, not lead them, says Ms. Rudder.

“Her recipe is kind of what we think of when we think of pumpkin pie. One quart of pumpkin stewed and strained, three pints of cream, nine beaten eggs, sugar, mace, nutmeg, and ginger laid into a paste – and she refers back to the recipe for the dough you should use,” she says.

There appears to be some universal agreement through the centuries – and across geopolitical borders – that although the pumpkin is sturdy, it doesn’t deliver the same palatable sweetness of butternut squash or the nutty flavor of acorn squash. Enter its companions of sugar and spices. “We cook pumpkin with piloncillo [brown sugar] and a little bit of water, cinnamon, cloves, and anise seeds. This gives it a lot of flavor, and we cook it until it is tender. Some people like to eat it in the morning in a bowl of warm milk with thick syrup. It is delicious,” says Ms. Martínez, describing calabaza en tacha (see recipe), or candied pumpkin, a traditional dish for Día de Muertos, an autumn Mexican holiday that honors loved ones who have died.

Ms. Martínez says pumpkins in Mexico were once cooked in tachos, large copper cauldrons used to make piloncillo. The pumpkins were softened in the molasses residue in the pots, leading to the name calabaza en tacha.

Sound familiar? Remember, the New England colonists also hollowed out pumpkins and filled them with milk and honey.

But how did the pumpkin get from Mexico to New England in the first place? It’s an agricultural mystery that invites the imagination. Perhaps the seeds spread in a slow creep, carried in the stomachs of migrating animals. Or perhaps they traveled in the pocket of an ancient wandering explorer curious about what lay beyond the next northern peak, sowing diplomacy and pumpkin recipes as she went.

Calabaza en tacha

From Mexicoinmykitchen.com

By Mely Martínez

Candied pumpkin, or calabaza en tacha, is a traditional dish served on Day of the Dead, Día de Muertos. It is also eaten in winter as a warm breakfast dish. Every region in Mexico has its own special way to prepare it, but usually the pumpkin is cooked in a piloncillo syrup with cinnamon sticks for a richer flavor. Piloncillo is unrefined sugar sold in solid form, typical of Central and South America, and can be substituted with brown sugar.

Serves 8

Ingredients

1 medium pumpkin, about 4 to 5 pounds

2 small piloncillo cones (can substitute 2 cups dark brown sugar plus 2 tablespoons molasses)

3 cinnamon sticks, whole

1 orange, sliced (optional)

4 cups of water

Directions

1. Cut the pumpkin in 3-inch serving-size sections. Remove seeds and strings if you prefer to use the seeds separately, or you can cook them with the syrup. Place piloncillo cones (or brown sugar and molasses), cinnamon sticks, and orange slices in a large pot.

2. Add 4 cups of water and bring to boiling, stirring occasionally. Once the sugar has dissolved, place some pumpkin pieces with the skin side down and then layer the rest of the pumpkin with the skin side up. Don’t worry about covering all the pumpkin with the liquid; the pumpkin will release water and the steam will cook the pumpkin.

3. Lower heat, cover, and simmer until the pumpkin is fork-tender and has soaked some of the syrup, about 15 minutes.

4. Once the pumpkin is cooked, remove from the pot using a large slotted spoon and transfer to a tray; cover with aluminum foil to keep warm.

5. Return syrup to boil on medium-high heat, stirring occasionally until it becomes thick. Return pumpkin pieces to pot and spoon syrup all over the pumpkin pieces. Discard orange slices and cinnamon sticks.

6. Serve pumpkin warm or at room temperature with a drizzle of syrup or in a bowl of warm milk. The pumpkin flavors will be better the next day, so save some for later.

‘I’m thankful’: A centenarian’s approach to life

What’s essential to a happy life? For this centenarian, gratitude for the good things in life has seen her through its trials – and leaves her counting her blessings to this day.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

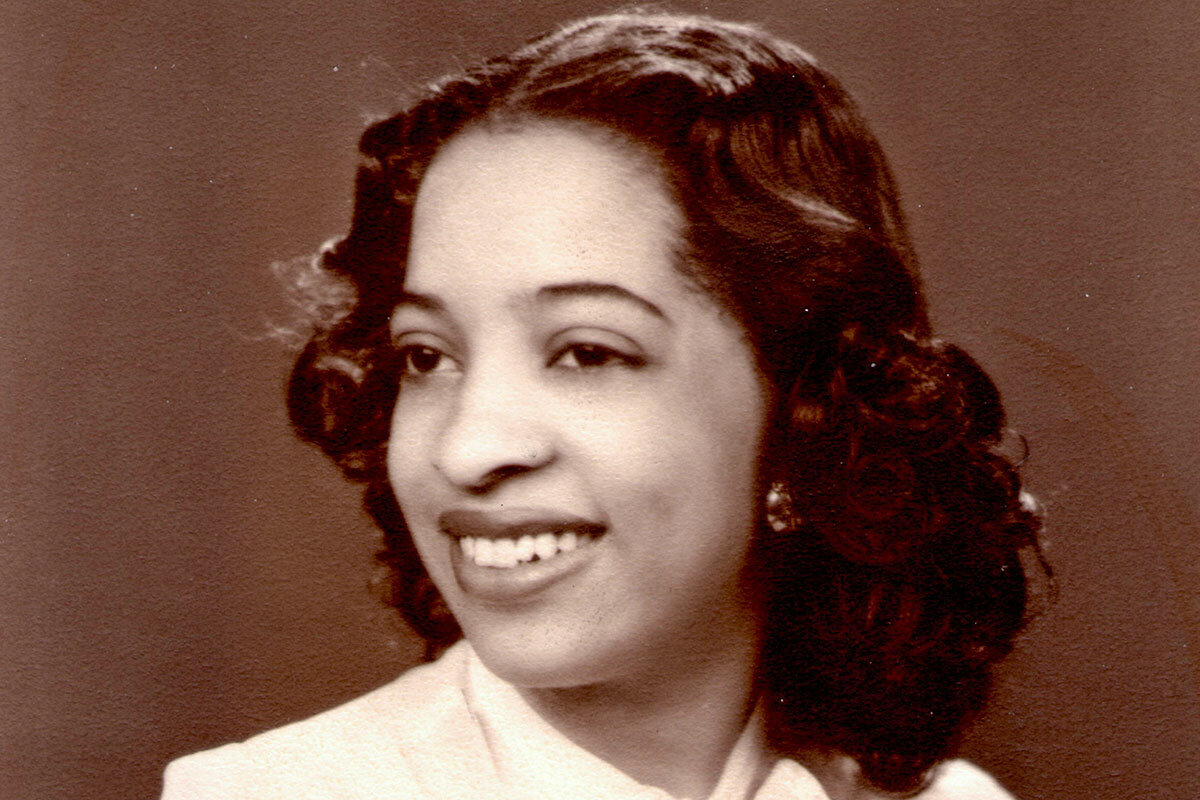

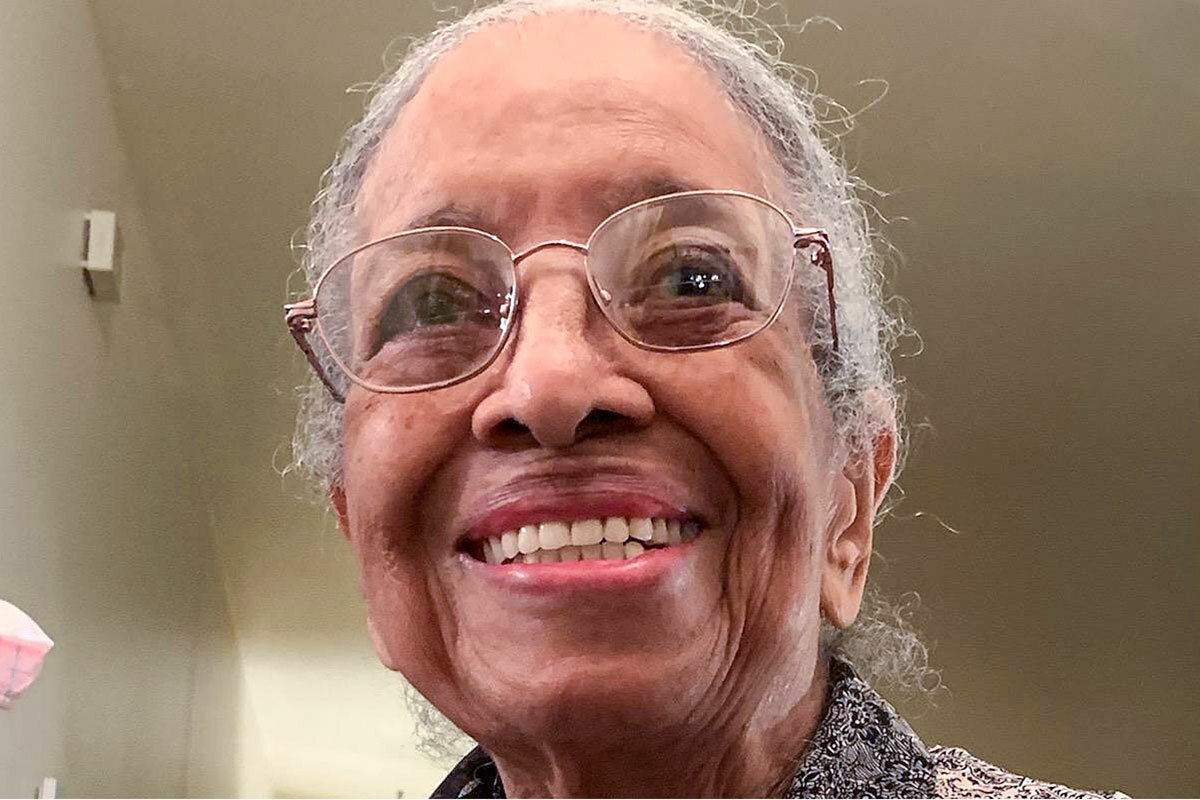

By Maisie Sparks Correspondent

Throughout the world, more people are living beyond the 100-year marker. And Martha Mae Dorsey Boles, age 103, is one of them. The mother of four, grandmother of seven, and great-grandmother of four, says gratitude has contributed to her longevity.

“When I can’t go to sleep, I think about all the good things that went on in my life, and then I have such good sleep and good dreams,” she says.

One of the many good memories she’s thankful for is listening to a fellow student at Chicago’s Fuller Elementary School play the piano during assemblies. That young man was Nathaniel Adams Cole, known to the world as Nat King Cole, a jazz pianist, singer, and the first Black man to host a nationally broadcast television show.

Mrs. Boles says she’s also learned that some things need to be forgotten if you’re going to be happy. “If something disturbs me, I just throw it out of my mind,” she says. “Life has disappointments, but I put them aside. My mother used to say, ‘Love will cure everything.’ It’s certainly kept me going … and I’m thankful.”

‘I’m thankful’: A centenarian’s approach to life

If age is more than a number, what else is it? For Martha Mae Dorsey Boles, age 103, it’s also an increased sense of thankfulness. Mrs. Boles was born in 1918, the last time there was a pandemic. She was too young to remember that public health crisis, and for this one, she’s too lovingly sheltered by her family to be exposed to its harm.

Throughout the world, more people are living beyond the 100-year marker. In the U.S., the Census Bureau predicts there will be more than 130,000 centenarians by 2030. That’s a small number of people as a percentage of the country’s nearly 334 million citizens. But centenarians are worth watching because it’s not just their length of days but also their quality of life that makes knowing more about them vital to us all.

While science has acknowledged many factors leading to longevity, Mrs. Boles, the mother of four, grandmother of seven, and great-grandmother of four, credits one more: gratitude. She says being thankful for the good things in life has played a role in her overall health, especially now that she’s in her 100s.

“When I can’t go to sleep, I think about all the good things that went on in my life, and then I have such good sleep and good dreams,” says Mrs. Boles. Longevity has been a family tradition: Her mother lived to be 99, and three of her six siblings well into their 90s.

Memories of history in the making

Some of the good memories she’s thankful for include listening to a fellow student at Chicago’s Fuller Elementary School play the piano during assemblies. That young man was Nathaniel Adams Cole, known to the world as Nat King Cole, a jazz pianist, singer, and the first Black man to host a nationally broadcast television show. She remembers her younger sister, Anita, playing with Gwendolyn Brooks – the first Black recipient of a Pulitzer Prize and Illinois’ poet laureate for more than 30 years.

There are memories of her DuSable High School friend Timuel Black, the Chicago historian and civil rights leader. Mr. Black, who died this year at 102, and Mrs. Boles frequently attended a school reunion that honored civics teacher Mary Herrick, until the pandemic curtailed the annual gathering.

“Miss Herrick, a white woman – all the teachers were white back then – shared African American history with us, even though it wasn’t in our schoolbooks,” recalls Mrs. Boles. “She also gathered us at her home to talk to and meet Black leaders. Once James Weldon Johnson was there.” (A poet, Johnson wrote “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often referred to as the Black national anthem.)

An avid reader as a child, Mrs. Boles brings new meaning to the term “lifelong learner.” Though her eyes are not what they used to be, learning hasn’t stopped, just changed media. Now, she learns by listening to the news and documentaries on public television. She is especially curious about the decades of her childhood.

“I can get on the computer and learn about anything,” she says, “I was sheltered by my parents. It wasn’t until I was a young woman that I realized that they kept a lot of things from us when we were growing up. There was a civil rights worker whose home was burned down. It was near ours. I didn’t know about that until much later in life because my family didn’t talk about hurtful subjects.”

“Love will cure everything”

What was shared, notes Mrs. Boles, was her parents’ faith, something she still finds important. This learning came more by what John Dorsey, a Baptist, and Mattie Mae Horner Dorsey, an Episcopalian did – not what they said. “My parents were quiet people,” says Mrs. Boles of her father, who worked as a hotel waiter, and her mother, a homemaker. “They let lots of people room with us until they could find a job and get settled. This was when the Great Migration was happening, and Black people were moving up from the South.”

One person who stopped by the home was a 10-year-old boy, George Boles. He was there with his grandfather, who was visiting a friend staying at the Dorseys’ home. Some years later, Martha Dorsey and George Boles met again, wed in 1947, and reared their children, remaining close until his passing in 1999. “I never felt more loved,” she says of their union.

As she’s moved along in years, Mrs. Boles has come to know that things that were once considered deficits can become assets. “I always was the slowest person in the family,” she says. “My sisters used to tease, ‘Martha is slower than molasses in the winter.’ But being slow and careful is a lifesaver now. People are doing things so speedy today, and it’s just getting speedier as the years go by. I don’t cook now, but I used to take my time cooking. Now I take my time eating. If you enjoy something, you should take your time with it.”

Not one to be rushed, Mrs. Boles never drove a car, although she did take driving lessons. “I liked riding the streetcars,” she says.

Grateful for life and the gift of having many good memories, Mrs. Boles has learned that some things need to be forgotten if you’re going to be happy. “If something disturbs me, I just throw it out of my mind,” she says. “Life has disappointments, but I put them aside. My mother used to say, ‘Love will cure everything.’ It’s certainly kept me going ... and I’m thankful.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Shared blessings as Afghans settle in the US

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Tens of thousands of Afghan refugees are now being settled across the United States, just weeks after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban. In fleeing religious persecution, these weary pilgrims are now telling journalists of their ordeals and those left behind. Most of all, they speak of the warm hospitality in the U.S., first at military bases and then by local communities.

“The one thing they wanted Americans to know is how grateful they are for everything that’s been done to protect them and their families,” wrote a reporter for the Patriot-News in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

It is not only the refugees who are grateful. Many if not most of them helped serve U.S. interests in their country following the ouster of the Taliban two decades ago after the 9/11 attacks. The U.S. owes them a dignified welcome, says Jack Markell, who is overseeing the federal government’s role in resettling Afghan refugees.

Hospitality often serves as a great equalizer between strangers. It is a recognition of an underlying goodness, or love in action, that banishes social frictions and binds people. It can be a moment of shared blessings.

Shared blessings as Afghans settle in the US

Tens of thousands of Afghan refugees are now being settled across the United States, just weeks after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban. In fleeing religious persecution, these weary pilgrims are now telling journalists of their ordeals and those left behind. Most of all, they speak of the warm hospitality in the U.S., first at military bases and then by local communities.

“The one thing they wanted Americans to know is how grateful they are for everything that’s been done to protect them and their families,” wrote a reporter for the Patriot-News in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

For many Afghan nationals, the gratitude can be immediate, according to Alejandro Mayorkas, secretary of homeland security.

Upon arriving in the U.S., many Afghan children are handed an American flag and “their fathers instinctively place a hand over their hearts in gratitude and in reverence for what this country has done for them: saved them, provided them a place of refuge and a new home,” he says.

It is not only the refugees who are grateful.

Many if not most of them helped serve U.S. interests in their country following the ouster of the Taliban two decades ago after the 9/11 attacks. The U.S. owes them a dignified welcome, says Jack Markell, a former Delaware governor who is overseeing the federal government’s role in resettling Afghan refugees.

In some communities, Americans are using the Thanksgiving holiday to show their appreciation. “I couldn’t imagine spending Thanksgiving doing anything other than trying to welcome them and make them feel a little bit more at home,” one teenager, Katie Harbaugh, told The Plain Dealer in Cleveland. Her father, Navy veteran Ken Harbaugh, has rounded up donations from other veterans and local donors to deliver meals to the refugees. “It’s all about welcoming the newcomer,” Mr. Harbaugh said.

These American expressions of gratitude provide a rare moment in the U.S.

“Americans from all walks of life have come forward to say, ‘We understand that these are people who stood with us and that it is time for us to stand with them,’” says Cecilia Muñoz, an organizer of a new nationwide group, Welcome.US, that is mobilizing donors to assist the refugees. “This is a unifying exercise,” she told The Chronicle of Philanthropy. “This is something which is bringing together people who might otherwise not be connected – across political lines and across other things which typically divide us.”

Kindness and hospitality often serve as a great equalizer between strangers. They are a recognition of an underlying goodness, or love in action, that banishes social frictions and binds people. It can be a moment of shared blessings.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The blessings of a grateful heart

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

At Thanksgiving and always, genuine gratitude for God’s goodness and love brings strength, peace, and healing, as this poem conveys. (Read it or listen to it being sung.)

The blessings of a grateful heart

A grateful heart a garden is,

Where there is always room

For every lovely, Godlike grace

To come to perfect bloom.

A grateful heart a fortress is,

A staunch and rugged tower,

Where God’s omnipotence, revealed,

Girds man with mighty power.

A grateful heart a temple is,

A shrine so pure and white,

Where angels of God’s presence keep

Calm watch by day or night.

Grant then, dear Father-Mother, God,

Whatever else befall,

This largess of a grateful heart

That loves and blesses all.

– Ethel Wasgatt Dennis, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 430, © CSBD

Audio attribution:

Words: Ethel Wasgatt Dennis

Music: James R. Corbett

Words © 1932, ren. 1960 The Christian Science Board of Directors

Music © 2017 The Christian Science Board of Directors

Music recording ℗ 2017 The Christian Science Publishing Society

A message of love

Joyful greeting

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. With the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States Thursday, the next issue of the Daily will be Monday, Nov. 29. But keep an eye out for a special edition on Friday that showcases our new podcast on People Making a Difference.