- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Here’s the scoop on Joe Biden and ice cream

President Joe Biden loves ice cream, especially any flavor involving chocolate. “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, but I eat a lot of ice cream,” he once famously said.

Thus, when we in Tuesday’s press pool got a heads-up that President Biden was going on an unannounced outing, we surmised it may involve a certain frozen treat. Which it did.

But business first: Upon arrival at Barracks Row on Capitol Hill, we all jammed into a little gift shop called Honey Made, where Mr. Biden chatted with the owner, bought a few things, and took questions from the pool on Russia and Ukraine. The visit’s purpose, we were told, was to highlight the growth in small business. It also reflected his pledge to get out more and talk to people.

Next up, a sidewalk chat with some Marines – then the gustatory highlight, a quick walk to Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams. The pool was left outside, TV cameras pressed against the window to record the action. Soon Mr. Biden emerged, brandishing a double-dip cone – reportedly, salted peanut butter ice cream with chocolate flecks plus a scoop of blackout chocolate cake on a waffle cone.

Clearly, nothing is ever simple when you’re president. Critics asked, why is he going for ice cream with so many pressing matters on his plate? Why patronize an Ohio-based chain, when Washington, D.C., has its own excellent local brands?

And why ice cream in the middle of winter? On that, I can attest that Mr. Biden is not alone. Russians love to eat ice cream in winter. Perhaps, in a small way, it’s a bit of common ground with Vladimir Putin.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Unemployed Tunisians gave strongman a chance. Where are the jobs?

Democracy or jobs? The Arab Spring was still flickering in Tunisia, but multiparty politics wasn’t creating solutions. Now youths are growing impatient with the populist strongman they embraced.

Tunisian President Kais Saied waged a successful campaign and spent his first two years in office by speaking directly to disillusioned young Tunisians. He vowed to clean up corruption, and railed against a broken political system and deadlocked parliament.

When he assumed emergency powers, suspended parliament, and scrapped the constitution six months ago, his actions were seen as extinguishing the last remaining democratic flames of the Arab Spring. Yet young Tunisians celebrated his move as a course-correction.

Today, however, they are finding that the move from multiparty parliamentary politics to populism has provided no new answers to the socioeconomic woes that sparked their revolution in late 2010. Since Mr. Saied’s July 25 power grab, the cost of basic goods has increased by 40%, and unemployment rose from 17.8% to 18.4%. The unemployment rate for those younger than 34 is above 40%.

“We are children of the revolution. We revolted in 2010 because we wanted decent job opportunities and dignified lives. We thought Kais Saied would finally be the one to fulfill this promise,” says Anis Jlassi, who has not held a full-time job since taking part in Tunisia’s revolution.

“But the situation is the same,” he says. “The people guilty of corruption are still dominating everything, and we still can’t get a decent job. This is not what we wanted.”

Unemployed Tunisians gave strongman a chance. Where are the jobs?

Eleven years on from a revolution that overthrew a dictatorship and inspired pro-democracy uprisings across the Arab world, young Tunisians concerned with a lack of economic opportunity are finding themselves in a frustratingly familiar position.

Tunisia’s democratically elected president, Kais Saied, waged a successful campaign and navigated his first two years in office by speaking directly to disillusioned young Tunisians. He vowed to clean up corruption, and railed against a broken political system and deadlocked parliament.

When he assumed emergency powers, suspended parliament, and scrapped the country’s constitution six months ago, his actions were seen as extinguishing the last remaining democratic flames of the Arab Spring. Yet young Tunisians celebrated his move as a course-correction.

Today, however, they are finding that the move from multiparty parliamentary politics to populism has provided no new answers to the socioeconomic woes that sparked their revolution in late 2010 and which have deepened with the pandemic.

“We are children of the revolution. We revolted in 2010 because we wanted decent job opportunities and dignified lives. We thought Kais Saied would finally be the one to fulfill this promise,” says Anis Jlassi, age 28, who has not held a full-time job in the decade since he took part in Tunisia’s revolution.

“But the situation is the same,” he says. “The people guilty of corruption are still dominating everything, and we still can’t get a decent job. This is not what we wanted.”

Higher prices, fewer jobs

Since Mr. Saied’s July 25 power grab, the cost of basic goods has risen by 40%. Chicken costs 50% more. Clothes, too.

Over the same period, overall unemployment rose from 17.8% to 18.4%, and the spread of the COVID-19 omicron variant led the government to reimpose evening curfews just last week.

But most importantly, young people still don’t have jobs. The unemployment rate for those younger than 34 is above 40%.

Yet their revolutionary fervor remains.

“We have a saying in Tunisia: The tongue has no bones,” says Riyadh Hami, a 27-year-old unemployed Saied supporter. “All we have seen is talk, without being backed up by anything solid on the ground,” he says, sitting in a cafe in the working-class Tunis neighborhood of Zahrouni. “We won’t wait forever.”

Saied’s true test

Today Mr. Saied rules alone, wielding presidential edicts and a hand-picked government.

At his direction, on Jan. 14, security forces violently cracked down on pro-democracy protesters gathered in downtown Tunis to mark the revolution’s anniversary, resulting in dozens of arrests, injuries, and one death.

But his true test is facing the hopes, expectations, and frustrations of young Tunisians who overwhelmingly voted for him.

Mr. Jlassi and his friends in the hardscrabble Hay Ettadhamen neighborhood in Tunis say they were initially won over by Mr. Saied, who visited multiple times while on the campaign trail and spent hours listening to their concerns.

When Mr. Saied suspended parliament and assumed emergency powers in July, Mr. Jlassi and young people across Tunisia danced in the streets. But the euphoria has dissipated.

Mr. Jlassi and his friend Khaled rely on the occasional job in construction or the odd shift as a KFC deliveryman.

Badri Hmaidi, a 35-year-old father of two who owns a clothing outlet across the street, is unable to move stock or pay the rent.

“More than 100 days have passed and we have seen nothing clear from Kais Saied except for rising prices,” Mr. Hmaidi says.

Running the economy

Tunisians agree on the economy’s structural and institutional challenges.

The financial and monetary system remains largely unreformed from the era of strongman Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. Doing business, getting licenses, and simply sending money can be a bureaucratic nightmare – scaring Tunisians and foreigners alike away from starting new businesses or expanding existing ones. There is a disconnect between university graduates and labor market needs.

Tunisia faces debt levels of 90% of gross domestic product; negotiations between the government and International Monetary Fund over a $4 billion bailout loan have been stuck in limbo.

In their time in office, political parties in parliament grappled with the identity of the country, democracy, and a host of deep-seated institutional challenges left behind by decades of dictatorship, rather than stewarding the economy.

The lack of tangible improvement led large swaths of Tunisians to turn against not only political parties, but parliament itself, paving the way for Mr. Saied’s power grab.

“Perhaps we could have paid more attention to the day-to-day economy and prices, but certain blocs were determined to obstruct and stop parliament’s work,” says legislator Faiza Bouhlel, as she last week ended a monthlong hunger strike protesting against Mr. Saied’s power grab.

“In the last parliament we passed 99 pieces of legislation in 1 1/2 years, but we lost the battle for the media narrative,” says Ms. Bouhlel, a member of parliament from the Islamist Ennahda party for the town of Sfax.

Different priorities?

Mr. Saied and his supporters preach patience, saying his government must first “cleanse” the Tunisian state of what the president describes as “corrupt people,” “criminals,” and “administrative incompetents,” before making headway on the economy.

The president is currently taking on the judiciary, some of whose members date to the Ben Ali era yet stand as the last institutional guardrail in the separation of powers.

“Our message to the people is: Be patient,” says Salah Mait, an unemployed IT specialist who leads a pro-Saied group.

“In 2010-11 there was a popular revolution, but Islamists and corrupt businessmen hijacked it. This is a course-correction of the last 10 years. We are saving the revolution, but we need to wipe the slate clean first.”

As part of the new slate, Mr. Saied, a constitutional law professor, is drawing up a new constitution to be put forward in a referendum later this year.

Rather than build the new constitution through an inclusive national dialogue, like the Nobel Prize-winning troika that drafted Tunisia’s 2014 constitution, he is set to draft it himself with citizens invited to provide input via an online survey being billed as a “citizens’ consultation.”

In the central Tunisian city of Sidi Bouzid, at a cafe across the street from where fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself afire in December 2010 and ignited the Arab Spring, Haikeel Azzeri, age 25, is more than willing to give the Tunisian president time.

As a candidate, Mr. Saied came to Sidi Bouzid multiple times, sat in the cafe where Mr. Azzeri works, and vowed to follow through on their revolutionary dreams of a better life.

“The revolution that we started right here in Sidi Bouzid was stolen by the politicians in Tunis. Kais Saied is giving us our revolution back,” says Mr. Azzeri as he slings an espresso behind the bar.

“Tunisia is a good country with potential, and parliament let it down,” Mr. Azzeri says, warning that “the same political parties and vested interests that spent the last 10 years destroying the country are trying to sabotage Kais Saied’s reforms.”

Yet for many, the nature of Mr. Saied’s reform agenda remains unclear.

Out of 20 young Tunisians interviewed for this story, only one had heard of the online consultations on the constitution; none said a new constitution was their priority.

“What Tunisia needs right now isn’t another constitution; it needs economic reforms and investments,” Sami Amri, a 26-year-old accountant, says as he walks past the memorial statue of Mr. Bouazizi’s fruit cart in Sidi Bouzid. “We should give the president three years to make the radical changes we need.”

As the economy worsened, Mr. Saied’s approval rating dropped from a high of 82% when he suspended parliament last July to 67% in December, surveys show. Despite frustrations, 76% of Tunisians said they would vote for him in the next election.

Clock is ticking

But analysts warn that blaming economic woes on a “corrupt system” and political foes stifling reforms only has so much mileage as the economy down-spirals further.

“Just like in 2011, the people who demonstrated in support of Saied did not do so because they want his political project or they didn’t like the current constitution; they did it for socioeconomic reasons,” says Youssef Cherif, political analyst and director of Columbia Center Tunis.

“The economic situation did not improve for Tunisians after 2011, and it has not improved since July 25 of last year. Kais Saied risks making the same mistake political parties did over the last decade.”

Young Tunisians are quick to remind the president that the clock is ticking and that they are more than willing to once again revive their revolutionary spirit.

“Before there were too many political parties and MPs to hold anyone to account for the country’s direction,” says Mr. Jlassi, the Hay Ettadhamen resident. “With Kais Saied, there is one person taking responsibility for the country, and we can hold that one person responsible.”

His friend Khaled slaps the cafe table.

“If he fails, we will hold another revolution, go out and say in a collective voice: Saied, leave!”

A deeper look

Teaching race in schools: Have these moms found a way forward?

In a town roiled by teaching about race in public schools, some moms are quietly fostering reconciliation through a simple idea: sitting down and getting to know each other.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Affluent. Good schools. A Confederate monument. A diversifying community.

This is Williamson County, just south of Nashville, one of the nation’s flashpoints over how race is taught and talked about in schools. On the surface, there are strict laws on the matter coming down from the state legislature, and fraught school board meetings.

But beneath the turmoil are people from diverse backgrounds trying to talk to each other about one of the most sensitive topics in America. Some would love to convince others of their convictions, and win them over to their “side.” But other groups are simply trying to understand each other’s views and cultivate a better sense of community.

“We’re learning from each other,” says Audrey McAdams, a Black mother of three. At the urging of Amie Cooke, a white acquaintance from her daughter’s day care, the two started leading a conversation group centered around diverse opinions on and experiences with race.

“It’s life-changing,” says Ms. Cooke.

Robin Steenman, of the local Moms for Liberty chapter, has whipped up opposition to public school curricula concerning race. Still, she sees a benefit in dialogue with neighbors who disagree.

“I don’t need an echo chamber,” says Ms. Steenman. “The best possible outcome is you convince him to come over to your way of thinking, but if we’re somewhere in the middle, that’s still a great thing.”

Teaching race in schools: Have these moms found a way forward?

Amie Cooke picked up her favorite coffee on her way to work and took a deep breath before pulling over to call Audrey McAdams, an acquaintance from her daughter’s day care.

Ms. Cooke, a white mother of three, felt a little anxious about asking Ms. McAdams, a Black mother who also has three children, to join her in forming a group to talk about one of America’s most sensitive topics – race. Specifically, she wanted to bring different people together to discuss racial reconciliation in their small town of Nolensville, Tennessee, where, like many communities across the country, tensions lurk beneath the surface and sometimes above.

It was the summer of 2020, soon after the death of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis, and Ms. Cooke was struck by a quote circulating on social media about how staying silent on the issue of racism wasn’t enough. She remembered hearing about Be the Bridge, a national Christian nonprofit that brings people together for healing conversations on race, a few years earlier. She searched for a local chapter and found none. So she asked herself: Do I have the confidence to find a co-leader and start a group?

“I was honestly not wanting to be a leader; I just wanted to join,” recalls Ms. Cooke. “But I realized this is it; I’ve got to do it.” She’d always hit it off with Ms. McAdams at school events and their daughters were friends, so she pulled up her contact list and sent a text message asking to talk.

Ms. McAdams, chatting between work meetings, greeted the idea with enthusiasm. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, wow,’ this is a way to continue the conversation with people I don’t know,” says Ms. McAdams. “I wanted to make sure it wasn’t just going to be a social thing, but something I could get behind and be passionate about and would make an impact.”

Ms. Cooke and Ms. McAdams still lead weekly gatherings of a group of women in Nolensville who are Black, white, and Hispanic and who want to learn about how race affects their lives and how to best treat others. They are one of a number of groups in Williamson County, Tennessee, that are trying to bridge divides between people of different backgrounds at a time of deepening rancor over race and history – particularly how the two are taught in public schools.

Williamson County, one of Tennessee’s wealthiest and fastest-growing areas, has emerged, like Loudoun County, Virginia; and Southlake, Texas, as a particularly fraught site for conflict. A video showing attendees threatening speakers with chants of “we know who you are” and “we will find you” after a school board meeting last summer addressing critical race theory – and masks – garnered widespread headlines.

While divisions within Williamson County still run deep, with nasty social media exchanges and heated education meetings, efforts persist underneath to insert a degree of respect and civility into the community’s racial reckoning.

“I really believe that the way forward is together, and healing comes from loving across differences,” says Jennifer Cortez, a mother of four who in February 2020 co-founded the group One WillCo to advocate for more racial equity and inclusion work in Williamson County Schools.

But questions linger. Are the voices of people in these groups being heard? Is their work making a difference?

Williamson County is an increasingly affluent area just south of Nashville that is suspended between the past and the future. It is dotted with Civil War sites and antebellum homes that pay homage to its rich history as part of the Old South. But it is also laced with spacious suburban homes, trendy boutiques and restaurants, and top-ranked schools that herald its emergence as a platinum appendage of encroaching Nashville.

To get here, you drive south out of the capital city on Highway 65 alongside knobs of rolling hills. The county includes six main cities and towns, of which Franklin, named after Founding Father Benjamin Franklin, is the county seat.

As you approach the county’s main hub, signs designate points of interest, including a former plantation and the site of one of the bloodiest conflicts of the Civil War, the Battle of Franklin. Once in the city of 83,000, cars wind through a picturesque downtown of antique shops, galleries, and red-brick Victorian buildings.

The area is growing rapidly but is also diversifying. Though Williamson County is about 88% white, the share of “students of color in the average white student’s school” has risen by about 10 percentage points since 1994, according to an NBC News analysis. The median household income in the county is $113,000.

Race has become an increasingly discussed and debated topic here. At a roundabout in the center of Franklin, a 37-foot-high monument honoring Confederate soldiers has stood for more than 100 years. In October 2021, a statue of a U.S. Colored Troops soldier was added to the square across from the Confederate memorial. The new statue is part of a “Fuller Story” project started by local pastors and a historian in 2017 after the Unite the Right rally that drew hundreds of white nationalists and their supporters to Charlottesville, Virginia.

“What can we do to be proactive?” Kevin Riggs, senior pastor at Franklin Community Church and one of the organizers involved in the project, recalls asking. “When something like that happens, we’re always turning to pastors for healing. What can we do to be proactive so Charlottesville doesn’t happen here?”

The group raised private funds to build the statue, which it believes is the country’s only U.S. Colored Troops monument in a downtown public square, and added five historical markers describing topics such as local race riots and the slave market that used to stand on the site.

Mr. Riggs, who is white and grew up in Nashville, doesn’t recall learning much about slavery in school other than that “it was bad and the Civil War erupted in the context of states’ rights.” He says the Fuller Story project is an effort to change the narrative so the “Lost Cause” myth of the Civil War – which attempts to recast the Confederate defeat in heroic terms and downplay the role of slavery – isn’t prolonged and slavery isn’t glossed over.

Local schools are now teaching a more accurate history of the Civil War and racism, says Mr. Riggs, who believes this development has caused a “whitelash.” He says it has spurred some residents to get on school boards, ban books they deem offensive, and oppose the teaching of critical race theory (CRT), when, he says, it’s not actually being taught in schools. He hopes efforts such as the Fuller Story bring some unity to Franklin, with people stopping to read and take pictures of the new memorial in the heavily trafficked area.

Yet clashes continue to reverberate over what’s being taught in public schools.

In March 2021, Robin Steenman, a former bomber pilot for the U.S. Air Force in Afghanistan and now full-time mother of three, was driving to pick up her son from preschool. She was tuned into a station that mentioned Moms for Liberty, a national advocacy group.

Ms. Steenman was intrigued by the organization, which was founded in January 2021 by Florida mothers wanting to champion “liberty and parental rights” in education. She tucked the idea away.

A month later she started a Williamson County chapter, concerned that critical race theory was sneaking into local schools through curriculum changes and diversity efforts. She gathered 19 neighbors for her first meeting and quickly organized public events. In May 2021, nearly 500 people attended a “CRT 101” event that the chapter sponsored.

Ms. Steenman is upset over a public school curriculum that she says is centered “more on feelings than on historical facts or objective truth” and teaches students to focus too much on each other’s skin color. She worries public schools are creating a society where children like hers will be a “persecuted class,” even though she’s enrolled her own kids in private schools.

With her military training, Ms. Steenman says she is mission focused and doesn’t get bogged down in dramas. To critics, her group is running a destructive campaign that’s sowing division in the county.

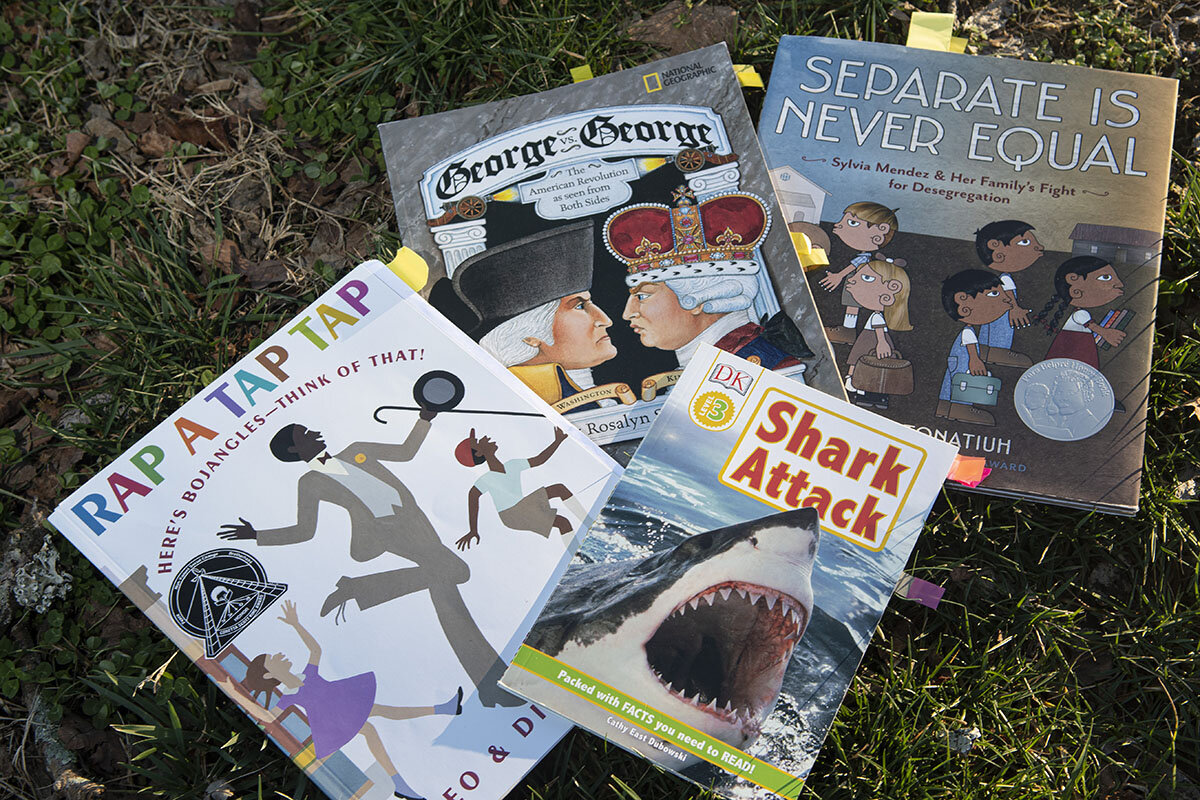

Her group filed a challenge against Williamson County Schools’ new English language arts curriculum, Wit and Wisdom, and school administrators reviewed 31 texts as a result. Moms for Liberty contended the books were not age-appropriate and taught young children divisions based on race. The books included “The Story of Ruby Bridges,” the girl who desegregated schools in Louisiana, and “Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington,” which were challenged based on too many pictures of angry white people, and the way the story is told, without enough focus on progress or redemption.

In late January, Williamson County Schools released a report recommending that the district continue to use all but one of the challenged texts in the Wit and Wisdom curriculum. The report also suggested, however, that teachers adjust how they present material in seven of the books, such as skipping certain pages.

School administrators here insist CRT is not taught in local classrooms. They point out that diversity work is necessary for the district to welcome all students, including students of color who raise instances of racism in their schools and worry that if they report them they will be ignored.

“I’ve got to be blunt. We’re not teaching critical race theory,” said Superintendent Jason Golden at his 2021 State of the Schools address. “Critical race theory, as it’s defined by those who are asking, is designed to make someone feel guilty, in essence as a result of their race; we’re not. But what we are doing is finding ways to help all our students feel safer in their school.”

Until last year, CRT was largely unknown in the United States. Its academic origins are traced to the 1970s when law scholars hashed out the theory, which considers the ways race and racism influence American law.

The term exploded in political and media usage in 2021 due largely to the efforts of conservative activist Christopher Rufo, who saw references to CRT scholars in anti-bias training materials and drew links in their work to Marxist scholars. He took his case against CRT to Tucker Carlson’s show on Fox News, where it was viewed by then-President Donald Trump, who subsequently issued an “anti-CRT” executive order regarding racial bias training. Conservative news hosts increased their mention of CRT from 132 times on air in 2020 to nearly 2,000 times in the first half of 2021, according to The Washington Post.

Nine state legislatures, including Tennessee’s, passed laws in the spring of 2021 banning schools from teaching concepts they say are found in CRT, such as that people can be inherently racist based on their race. At least 14 other states introduced or debated such laws.

While K-12 educators across the country deny CRT is part of their lesson plans, critics charge that diversity and equity initiatives, or teaching about white privilege, exemplify CRT in action.

“We’re at a moment where school leaders are trying to find ways to create a more inclusive learning environment, an environment that reflects all people and ideas, and you have a faction of our society who for better or worse tend to be loudest and most coordinated where they just label such efforts as CRT,” says Jamel Donnor, an associate professor of education at the College of William and Mary in Virginia.

For the mothers involved in Be the Bridge, the idea wasn’t to focus on CRT. But it did, inevitably, seep into their conversations.

The women, who are all working mothers ranging from their late 20s to early 50s, began to gradually gain trust in each other through their regular Zoom meetings. Starting the meetings with prayer and extending “love and grace” to each other helped ease difficult conversations.

Ms. Cooke recalls one of their early sessions when a Black group member shared how her husband was stopped by a police officer while walking their dog in town. The officer asked what he was doing there. “I had no idea [this type of action] was happening this close to home,” Ms. Cooke says.

When CRT started dominating local school board meetings, members of Be the Bridge spoke at the forums in support of the district’s equity work and donated multicultural books to their school library.

The group has become so tightknit that they offer each other jobs and fashion advice and text each other almost daily. Most of their families are supportive, but a few friends and family members have questioned the need for the group and suggested that talking about race will just kick up more controversy.

Ms. Cooke and Ms. McAdams don’t give much heed to those views. Instead, they’re finding themselves talking more honestly about racial issues, and not just with people in Be the Bridge.

“The conversations in this group are so meaningful, but it also makes you more comfortable having conversations with other people outside of the group,” says Ms. McAdams, who points to a constructive conversation she had with a neighbor who is a part of Moms for Liberty about whether and how to talk to children about race in schools. Both parties walked away still friendly and understood each other better.

“In the past, I would have thought, ‘I’m not going to talk about this; let’s keep things easy,’ but tough conversations need to be had,” she says.

Other community groups are also trying to bring people together around what they see as often overlooked acts of discrimination. Revida Rahman, an executive from Brentwood, Tennessee, and mother of two sons enrolled in Williamson County Schools, contacted the district about five years ago with her husband and other Black families. They were concerned that field trips to a plantation didn’t fully address slavery. They said their children were also called racial slurs by classmates. The district formed a Cultural Competency Council, ran anti-bias training for staff, and hired a diversity consultant.

In late 2019, Ms. Cortez, who is white, contacted Ms. Rahman to see if they could work together to foster more understanding about why diversity efforts are needed. They wanted their group, One WillCo, to encourage a more civil tone in discussions between school leaders and parents in particular.

“We’re trying to have a different approach, a sense of calm, civility, respect, to communicate with others who disagree with us and have some productivity instead of yelling or being upset with those who disagree,” says Ms. Rahman.

Harmony Kennedy, a 10th grade student at Nolensville High School, who is Black, spoke in a One WillCo social media video about incidents she’s faced in school, such as when a classmate called her his slave after asking her to pick up his trash.

“I think they need to educate the teachers and the students as well on the remarks they make, and teach teachers how to handle the situations that happen,” says Harmony in an interview.

Ms. Cortez and Ms. Rahman are disappointed with division in the community around CRT, which they think has become politicized. Ms. Cortez planned to meet with Ms. Steenman of Moms for Liberty, but it fell through over COVID-19 concerns.

Other community members have formed relationships with Ms. Steenman even when they disagree with her. Lamont Turner grew up in Franklin, the only Black male student in his class at a private high school and a football star. Looking back, he sees how steeped in Southern Civil War culture he was, celebrating sports championships at the Confederate monument and whistling “Dixie.”

It wasn’t until more recently when his wife asked if he wanted to take a family photo in front of the monument that he started asking deeper questions about what it stands for. Mr. Turner started a blog and was invited by civic groups to talk about the need to understand how historical wrongs still bear on the present.

“That’s the only way we can truly heal. From any angle that you try to look at this, the truth is the actual healing nutrient that will help us go to where we want to go,” he says.

Mr. Turner and Ms. Steenman became acquainted after they participated in a community forum run by the diversity consultant hired by Williamson County Schools. Ms. Steenman asked to meet up.

Mr. Turner agreed to talk, and they started exchanging pictures of their families. Deep down, each person hopes the other will start to change their point of view, but they also enjoy building a friendship.

“I enjoy those meetings because I don’t need an echo chamber,” says Ms. Steenman. “The best possible outcome is you convince him to come over to your way of thinking, but if we’re somewhere in the middle, that’s still a great thing.”

“I have to meet Robin and my community where they are at,” says Mr. Turner. “That’s my intent when I engage with all sides. I try to lead with education, and in an educational spirit, I can’t go into a conversation thinking I know it all.”

The civility of some of these one-on-one encounters may be severely tested in the future. In what’s expected to add fuel to the CRT debate, Tennessee lawmakers recently passed a bill allowing partisan school board elections for the first time.

Both the Democratic and Republican parties in Williamson County announced they will field candidates for August 2022 elections – and no doubt the volume on issues surrounding race will rise.

“I think we’ll see more instances of this deep contention around CRT as we head into 2022 and the midterm election year,” says Ebony Duncan-Shippy, an assistant professor of education at Washington University in St. Louis. “The only way we can move beyond that is if all of the groups, all folks at the table see it in their best interest to do so.”

Ms. Cooke and Ms. McAdams have already added a shock-absorber depth to their relationship. Running Be the Bridge has moved them from being mothers who had a connection through their children at day care to becoming close friends. They’re open and honest with each other. They’re hoping to start other Be the Bridge chapters in the area. “I wish everyone could be a part of a group like this because it’s life-changing,” says Ms. Cooke while sipping coffee at Itty Bitty Donuts & Specialty Coffee in Nolensville.

Before getting up to head back to work, Ms. McAdams smiles and agrees. “We’re learning from each other. She’s learning from me; I’m learning from her. Our experiences may be different, but the more we talk the more I get that, I can see where you’re coming from,” says Ms. McAdams.

* This story has been updated to include the Williamson County Schools' recommendations about the books used in the district's new English language arts curriculum.

Burkina Faso coup: How democracy crumbled under jihadi stress

This week’s military coup in Burkina Faso revealed how jihadi violence is undermining democracy in West Africa. How easily can it be restored?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Clair MacDougall Correspondent

It is not often that military coups are popular, but the putsch this week in Burkina Faso drew enthusiastic crowds onto the streets of the capital, Ouagadougou.

That was a reflection of broad discontent in West African countries with civilian leaders who have proved unable to curb swelling Islamist violence. “There is a profound disillusionment with the democratic system, and to some extent people see a ray of hope in the military,” says one regional analyst.

Islamist insurgents have been exploiting local grievances and discontent with the authorities for over a decade in the Sahel, a vast band of semiarid scrubland south of the Sahara. They have recently gained a lot of ground in Burkina Faso, killing thousands and driving 1.5 million people from their homes.

The elected civilian government proved unable to stop them. The public has turned to the army, hoping for stepped up operations, following the example of their neighbors in Mali. Jihadi violence has pushed fragile democracies in West Africa beyond their breaking point.

Burkina Faso coup: How democracy crumbled under jihadi stress

The day after volleys of gunshots ringing through the streets of the capital last Monday signaled the ousting of Burkina Faso’s democratically elected president, 21-year-old Ibrahim joined thousands cheering in the streets.

“With the former regime, there was no peace, but now our hope lies with the putschists,” the high school student said, as he raised a fist and posed beside an image of a soldier on a mural in the Place de la Nation in central Ouagadougou.

His enthusiasm for the military coup reflects broader discontent in West African countries with civilian leaders who have proved unable to curb swelling Islamist violence, and who respond to criticism and protests by shutting down the internet and using tear gas.

“There is a profound disillusionment with the democratic system, and to some extent people see a ray of hope in the military,” says Fahiraman Rodrigue Koné, a researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, a regional think tank.

“People believe that democratically elected elites have failed to meet their basic needs,” he adds, especially the need for protection against increasingly violent raids by Islamist groups who have taken over wide swaths of northern Burkina Faso.

And with Africa’s vast population of young people riding a social media wave of Pan-Africanist and anti-European sentiment, some analysts believe that Burkina Faso’s will not be the last civilian government in the region to fall.

“Safeguard and restoration”

It is only a little over seven years since a popular uprising overthrew the country’s last military ruler, Blaise Compaoré, and young men like Ibrahim cheered the army’s departure.

But Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, the man elected president in 2015 and again in 2020, has been unable to stem jihadi violence. Last Monday, a group of soldiers calling themselves the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration announced in a televised broadcast that they had suspended the constitution.

They said they were taking over in part because of the civilian government’s inability to rein in an Islamist insurgency that has engulfed much of the once-stable nation of 21 million.

Africa’s generation of strongmen, seizing power in coups, is largely a thing of the past. But many fear that a new age of military rule or extensions of constitutional term limits could be dawning. Mr. Kaboré’s overthrow marks the third time that the military has seized power in a West African nation in the last eight months.

In neighboring Chad, the president’s death last year led to his army officer son taking over; to the south, in Guinea, Alpha Condé was ousted by a member of an elite special forces unit after attempting to change presidential term limits. The playbook is still open as far afield as Sudan, in East Africa, where military men have also taken control in recent years.

Lt. Col. Paul-Henri Damiba, the Burkinabé coup leader, appears to have been emboldened particularly by the young, Western-trained elite military men who seized power in Mali last year. There too, the coup was preceded by spiraling jihadi violence and a violent crackdown on protesters.

Jihadis have been exploiting local grievances and discontent with regional governments for over a decade, attacking already limited state institutions throughout broad swaths of the Sahel, a vast band of semiarid scrubland south of the Sahara desert.

For years, Burkina Faso largely escaped the violence that had roiled its neighbors. Mr. Compaoré, the former military ruler, reportedly enjoyed close links with some of the insurgent groups, Islamist or otherwise. That enabled him to keep them out of his backyard and often cast him in the role of mediator in the region’s multiple conflicts.

With Mr. Compaoré gone, jihadis who had been gradually gaining ground across the poor, unstable region since the end of the 1990s – despite many attempts by French and allied regional forces to expunge them – soon found fertile new ground in Burkina Faso. Since Mr. Kaboré took office in 2015, Islamist violence has displaced 1.5 million people, killed thousands, and sent civil servants, teachers, health workers, and other government employees fleeing in what was already one of the world’s poorest nations.

In November, an attack on a military base in the northern town of Inata that killed 49 soldiers and four civilians caused national outrage when it was revealed that the soldiers had run out of food. Protests broke out, demanding a stronger response to the security crisis, but the government cracked down on them.

Ibrahim, the high school student who asked that his family name not be used for his own safety, is no stranger to the turmoil. Three years ago, he helped his family evacuate their hometown of Tasmakatt, in the northern Sahel region, after men in turbans stormed the local mosque and ordered residents to leave the town within 72 hours. His herder family lost all their cattle and now live in Gorom Gorom, an area where violent attacks on civilians and security forces are also a regular occurrence.

“All we want is peace,” says Issa, a friend of Ibrahim’s whose family also comes from Tasmakatt and evacuated to Gorom Gorom.

A fraught path back to democracy

But the path to stable democracy in the Sahel remains fraught.

On the one hand, jihadi violence is stretching the region’s fragile and flawed democracies to breaking point. “Jihadist groups have exploited the limits of governments in West African countries, particularly when it comes to lack of access to justice and basic social goods,” says Mr. Koné, the political analyst.

Ironically, Western support for regional governments fighting Islamist insurgents may have highlighted those limits by undermining official accountability in West Africa’s fledgling democracies, says Anna Schmauder, a researcher with the Clingendael Institute in the Netherlands.

“Collaboration in the realm of counterterrorism … has been the prime focus and has effectively prevented accountability in the realm of human rights or anti-corruption and transparency,” she says.

On the other hand, military rulers have proved unwilling to hand back power easily. In Mali, the army recently announced a timetable that would postpone a return to civilian rule for four more years. The fear, says Corinne Dufka, West Africa director for Human Rights Watch, is that this will become “the template.”

Meanwhile, regional organizations have been unable to preserve democracy. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) suspended Burkina Faso on Friday; earlier this month it imposed economic sanctions on Mali, and promised more unless the government held elections next month.

But such actions come too late, Mr. Koné complains about ECOWAS. “They are not proactive and don’t take enough initiative to prevent these situations from happening,” he says. “They only intervene at the worst moment, like firemen.”

While many Burkinabés have cheered on the coup leaders, analysts say that their backing comes with conditions, and that many citizens might not support protracted military rule.

“The insurrection of 2014 [that unseated Mr. Compaoré] was clearly a demand from the population. They didn’t want to see the military ruling the country because they suffered for a long time,” says Paul Koalaga of the Institute for Strategy and International Relations in Ouagadougou.

Civil society groups appeared divided this week over how to react to the coup.

Coup leader Colonel Damiba pledged on Thursday that he would restore constitutional order to Burkina Faso “when the conditions are right, according to the deadline that our people will define in all sovereignty.”

For now, citizens like Issa and Ibrahim are waiting to see what unfolds.

“For the moment we are not able to say anything because they just came to power,” says Issa. “We will be observing.”

National anthem as a mandatory game-starter? Florida free-speech test.

A move by Florida legislators, aimed at making the national anthem a compulsory feature of sporting events, raises some big questions about free speech – especially in the context of wider turbulence over politics and race.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Gov. Ron DeSantis and other Florida Republicans are promoting their state as a bastion of liberty. To Mr. DeSantis, Americans are flocking to the state because it represents ideals like low taxes and the individual’s right to make health decisions around masks and vaccines.

But some recent policies in the state also amount to partisanship over the politically divisive issue of race – and some of those are coming in for criticism on free-speech grounds.

State lawmakers are debating a bill that would compel private sports teams to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at each game. It’s already a pregame tradition, but codifying it into law could run into First Amendment challenges.

“Sports are the closest thing we have to tribalism in the U.S. besides political parties nowadays – and political parties are losing a lot of their appeal,” says Steve Miska, president of First Amendment Voice, a nonpartisan think tank. “I think this is going to be a messy place” for the First Amendment.

For hockey fan Joe Ferraro, “The Star-Spangled Banner” is hardly divisive in itself. To him, it is a reminder that everybody belongs to a bigger team. Yet making it mandatory, he says, “does feel like communism.”

National anthem as a mandatory game-starter? Florida free-speech test.

The bellwether state of Florida now is amping up the volume in a nationwide discourse on race as a core facet of political culture wars.

Under Gov. Ron DeSantis, a potential top contender for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, the state has raised penalties for organizers of protests, banned teachers from putting the words “critical” and “race” next to each other in a sentence, and barred professors from testifying against state policies on voting rights and public health mandates. All of those moves carry racial implications. And many are headed for court: A judge issued an injunction against the “anti-riot law,” calling it ”constitutionally vague.”

Now state lawmakers are debating a bill that would compel private sports teams like the Jacksonville Icemen or Miami Dolphins to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” at each game. Note: This already is a pregame tradition for professional sports. Codifying it into law could run into First Amendment challenges.

Governor DeSantis has rhetorically situated the Sunshine State as “freedom’s vanguard.”

Yet many say moves by Republicans in Tallahassee to use the power of the state to arbitrate what citizens say, when they say it, and how they say it have put the Sunshine State at odds with the warning contained in a 1943 U.S. Supreme Court ruling penned by Justice Robert Jackson: that “no official ... can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”

That landmark ruling affirmed that the First Amendment protection of free speech shields public school students from being forced to salute the American flag or say the Pledge of Allegiance.

That the current debate is playing out partly in hockey rinks in Florida is no surprise to Steve Miska, president of First Amendment Voice, a nonpartisan think tank.

“Sports are the closest thing we have to tribalism in the U.S. besides political parties nowadays – and political parties are losing a lot of their appeal,” says Mr. Miska. “I think this is going to be a messy place” for the First Amendment.

The anthem as a focal point on race

Much like fisticuffs in hockey, the national anthem is part of the spectacle and entertainment.

But when primarily Black athletes began taking a knee during the anthem in solidarity with social justice protests over controversial instances of Black people being killed by police, then-President Donald Trump and many other conservatives saw it as a culture-war demarcation that could be used for political effect.

A decision by Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban to forgo the anthem at the height of protests over the murder of George Floyd in 2020 heightened the backlash.

When Texas passed the first law to mandate the anthem last fall, 10 of 13 Democrats in the state Senate approved it.

For David Papaj in Jacksonville, a fan of the Icemen, that kind of bipartisan support is a no-brainer. “I mean, what team wouldn’t play the national anthem? We’re Americans, right?”

A conservative brand of freedom

In that way, Governor DeSantis has argued that Florida is setting standards that patriots like.

In his view, Americans – including liberal ones – are flocking to Florida because it represents ideals like low taxes and the individual’s right to make health decisions around masks and vaccines.

“While so many have consigned the people’s rights to the graveyard, ... Florida has stood strong as a rock of freedom,” he said this month in his annual State of the State speech.

Governor DeSantis has painted himself as a First Amendment champion. Florida became the first state to impose sanctions against social media companies that “deplatform” politicians for violating their terms of service agreements around hate speech and spreading misinformation.

Now committees in the Florida Legislature are pushing forward a bill that would bar teachers from airing ideas that would cause any student “discomfort, guilt, anguish” or distress about their race, gender, or national origin. The bill pits itself against education efforts such as critical race theory, which, in the eyes of opponents, promotes white guilt for racial sins in the nation’s past.

Democratic lawmakers say the measure is effectively gagging teachers and making it impossible for people of color to speak about their own lived experience. “I’m not anti-American, but I am an American, and my voice matters just as much as your voice,” Rep. Ramon Alexander said in Tallahassee, speaking about the bill barring teachers from making students “feel uncomfortable” during lessons. At one point, he grew tearful talking about his own patriotism and singing the national anthem. “My reality matters as much as your opinion. And you can’t handle the truth.”

Anticipatory obedience

Courts have found evidence that lawmakers are also engaging in picking and choosing viewpoints, and using the power of the state as a way to enforce their preferred views.

The strategy, experts say, hangs on a legal concept called anticipatory obedience, or self-censorship for fear of retribution.

How it works was outlined in a recent U.S. District Court ruling that found the state-funded University of Florida system violated the constitutional rights of six professors by barring them from testifying on public health and voting rights, when their views would be at odds with state policy.

In a blistering ruling on Jan. 21, U.S. District Judge Mark Walker found that the university used an arbitrary approval process for professors to speak to courts or the media that caused “palpable reticence and even fear on the part of faculty to speak up” on hot topics.

In his ruling, Judge Walker said university administrators appeased lawmakers by comparing respected faculty to “moonlighters,” “robbers,” “traitors,” “political hacks,” and “disobedient liars.” The effect, wrote Judge Walker, is the chilling of speech by teachers whose viewpoints are of “transcendent value” to society.

“A democracy allows people to determine what the public opinion is,” says Robert Post, a law professor at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. “A country which is totalitarian wants to shape the nature of public opinion. It does that by preventing people from speaking, and it does it by requiring people to speak in ways that are false or they don’t believe. Both are fascist. That’s what you see evidence of here.”

Simmering tensions in society

A recent incident at Jacksonville’s hockey arena shows, at least to some, the problems with shutting down how people speak about a topic fraught with such enduring tension as race.

During overtime play, a Black player for the South Carolina Stingrays looked around to see a white Jacksonville Icemen player making what he called “monkey gestures” at him. The Black player, Jordan Subban, commenced to punch the white player, Jacob Panetta, in the face several times. The bench cleared.

Later, the Icemen cut Mr. Panetta from the roster, and he has been suspended for the rest of the season by the league, the ECHL.

Mr. Panetta apologized, saying he didn’t intend to make a racist gesture. He said he was taunting Mr. Subban for only fighting when referees are close by. Instead of a monkey gesture, Mr. Panetta said it was an “Oh, you’re such a big guy when the refs are around” bodybuilder gesture.

But for New Jersey Devils defenseman P.K. Subban, the brother of Jordan Subban, the taunts fit a larger pattern where papering over the past can give liberty to discriminate and hate in the future. It was the second alleged racial taunt by a white player against a Black one in the U.S. minor leagues in a span of a few days.

And those taunts came just days after a Florida House education committee stamped its support on what critics call the “white discomfort” bill.

“For us, this is life,” P.K. Subban told reporters last weekend. “This is life for us, and that’s what is sad. This is life for people who look like me who have gone through the game of hockey. And that’s part of the history, whether we like it or not.”

Mr. Miska, a retired Army colonel, spent 40 months on combat duty in the Middle East. Today, many of his veteran buddies struggle to understand tendencies by political leaders to use the state to either punish or compel speech to enforce or denounce a particular viewpoint – in a sense exploiting instead of seeking to bridge racial divides.

“The danger is what [Harvard professor] Arthur Brooks calls the ‘rhetorical dope peddlers’: people who profit from the division and the polarization,” says Mr. Miska. “And maybe that’s the norm for our country.”

For Icemen fan Joe Ferraro, “The Star-Spangled Banner” is hardly divisive. If fandom is tribal, then, to him, the singing of the anthem is a reminder that everybody belongs to a bigger team.

His father, a Marine, made him stand lock-straight whenever the national anthem played on the TV before a game. On Saturday night, there Mr. Ferraro stood, ramrod straight, baseball cap over his heart.

It bothers him that some Americans don’t seem to understand how respecting traditions can be a cornerstone of national unity.

Yet after having spent a career in the military himself, he senses a false note.

Forcing a team to play “The Star-Spangled Banner,” he says, “does feel like communism.”

In Pictures

Sea turtle rescuers race against cold

Good neighbors help community members in need. On Cape Cod in Massachusetts, residents carry that a step further to include flippered neighbors as well.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

As winter kicks into gear, many New Englanders hunker down indoors. But on Cape Cod in Massachusetts, a cadre of volunteers bundles up and heads to the beach. From November through January, they search the sands for cold-stunned sea turtles.

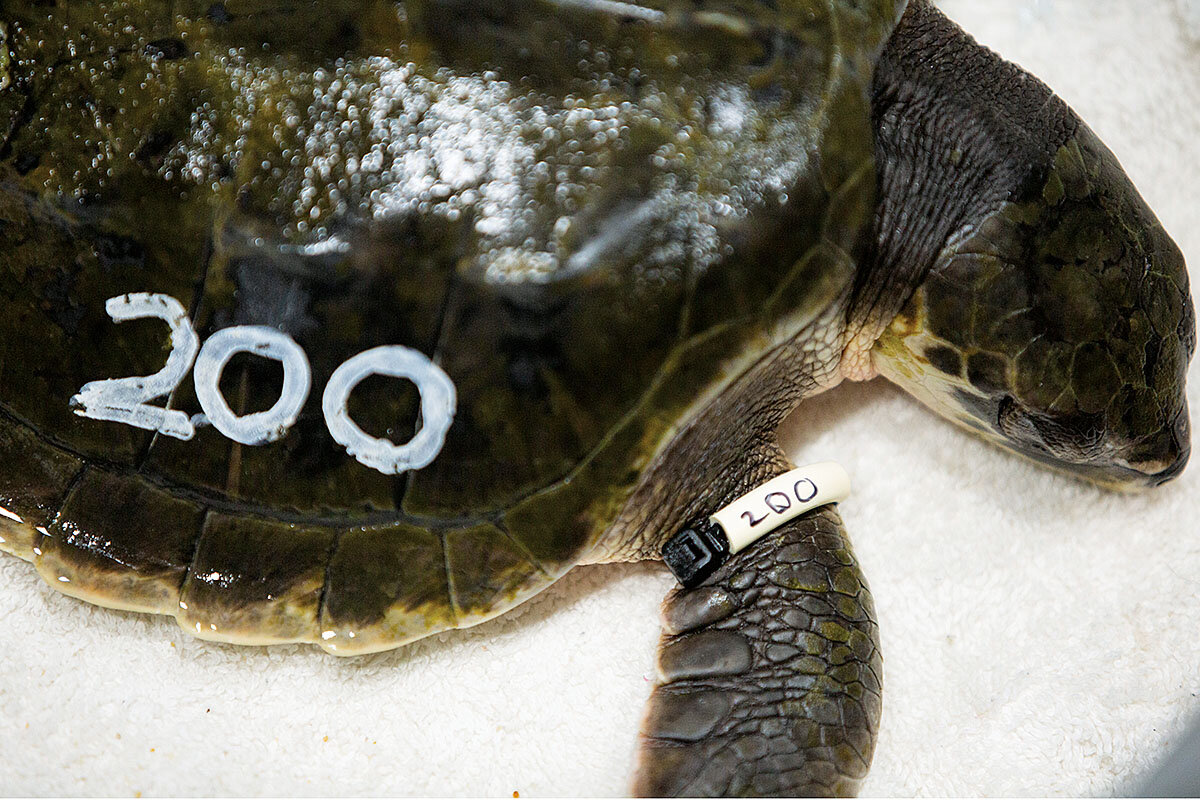

Each rescued animal is rushed to the intensive care unit at Mass Audubon Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary where they are weighed, measured, photographed, and assigned a number that will follow them on their journey to recovery.

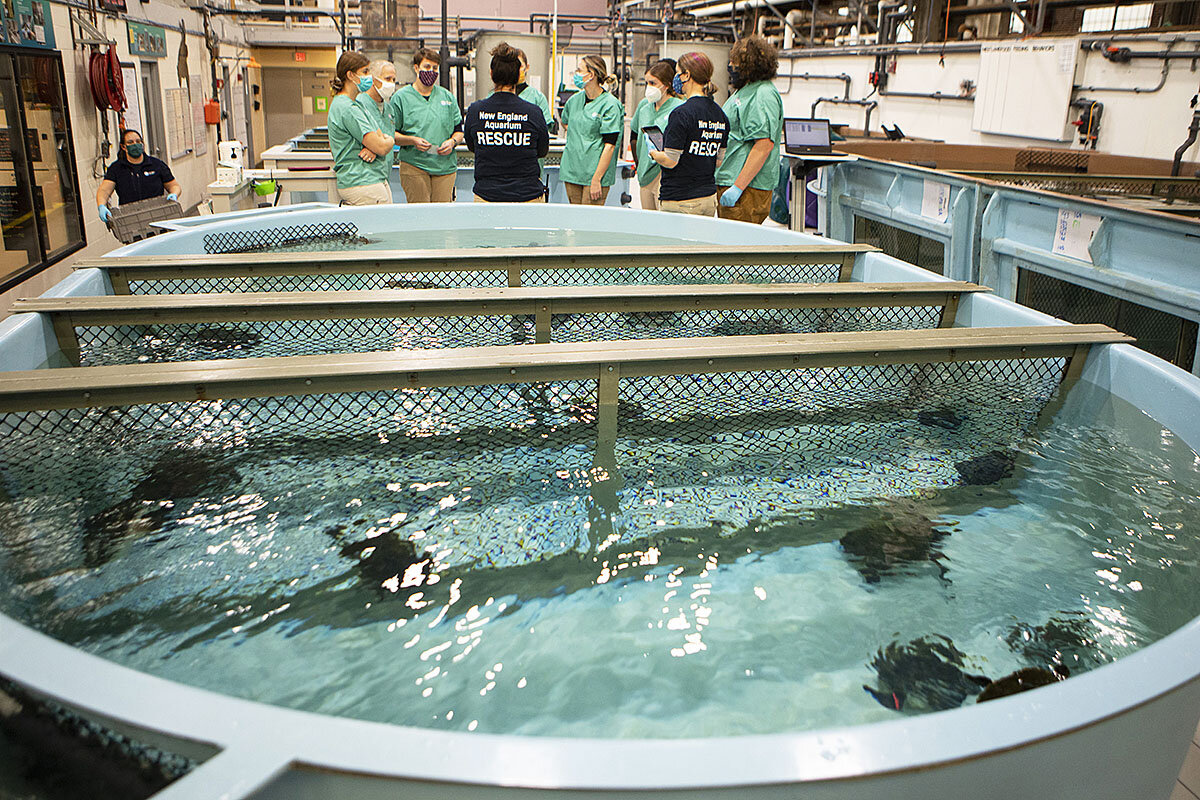

Once the turtles are stabilized, their next stop is the New England Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts, a cavernous space filled with multiple pools, expert staff, and lots of volunteers. After a thorough physical examination, they are placed in temperature-controlled pools where their behavior is closely monitored. If all looks well, they continue their journey on charter flights south to secondary rehabilitation centers. The healthiest will eventually be released back into their ocean home.

Sea turtle rescuers race against cold

Every winter in New England, as the ocean waters chill and frigid winds drive many residents indoors, a cadre of volunteers heads to the beach. Day and night they search the sands of Cape Cod Bay in Massachusetts for stranded sea turtles.

Most of these marine reptiles find their way toward warmer waters. But each year, especially after sudden drops in temperature, hundreds of sea turtles, particularly young ones, become cold stunned, tumbling in the waves and onto the shore, unable to eat, drink, or move. The Cape’s peninsular hook of land catches the fledgling reptiles as they belatedly try to head south. Animal lovers armed with plastic sleds, towels, headlamps, and training are on watch after high tides from November through January.

Each rescued animal is rushed to the intensive care unit at Mass Audubon Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary where they are weighed, measured, photographed, and assigned a number that will follow them on their journey to recovery. On one especially busy December day, 94 turtles arrived in need of urgent care; this season more than 500 have been treated.

Fortunately, most turtles are found alive, but those that are not are studied for research. Marine biologist* Karen Dourdeville, who coordinates the rescue efforts, says her staff has learned to warm the animals gradually (the room is kept at 55 degrees), to talk softly, and to handle the precious creatures as little as possible. The most frequently rescued species is the Kemp’s ridley, the rarest and most endangered sea turtle in the world. Green turtles, which are also endangered, and loggerheads are also frequent patients.

Once the turtles are stabilized, their next stop is the New England Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts, a cavernous space filled with multiple pools, expert staff, and lots of volunteers. Each turtle is given a thorough physical examination, and soon they are placed in temperature-controlled pools where their behavior is closely monitored. If all looks well, they continue their journey on charter flights south to secondary rehabilitation centers. The healthiest will eventually be released back into their ocean home.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a misidentification of Karen Dourdeville's expertise. She is a marine biologist.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why the gratitude for refugee-hosting countries?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since August when the Taliban took power, Afghanistan’s economy has virtually collapsed under the group’s harsh rule. Now the country has become one of the world’s largest contributors to a rise in refugees – more than 84 million total. Yet as foreign relief agencies try to stem the exodus by providing aid directly to the Afghan people, the United Nations is offering an additional response. It is heaping praise on nearby countries welcoming the fleeing Afghans.

Worldwide, gratitude for host countries has become essential for refugee agencies. More conflicts are protracted and leave displaced people in limbo longer. Over the past three decades, the average period of forced displacement has increased threefold. From Uganda to Colombia, more countries – most of them low- or middle-income – have had to learn to live with refugees.

Gratitude for the host nations serves as a moral counterpoint to the conflicts that drive people from their homes. It might also nudge more countries to adopt a similar welcoming spirit.

Why the gratitude for refugee-hosting countries?

Since August when the Taliban took power, Afghanistan’s economy has virtually collapsed under the group’s harsh rule. Now the country has become one of the world’s largest contributors to a rise in refugees – more than 84 million total. Yet as foreign relief agencies try to stem the exodus by providing aid directly to the Afghan people, the United Nations is offering an additional response. It is heaping praise on nearby countries welcoming the fleeing Afghans.

In December, Filippo Grandi, U.N. high commissioner for refugees, visited Iran and expressed gratitude for it being a generous host to Afghan refugees. In January, the U.N. refugee agency, UNHCR, commended Pakistan for its campaign to give identity cards to some 1.4 million Afghans in the country. The smart cards will enable them to better access services such as education and banking.

“It is important to keep a supportive eye on [Afghanistan’s] neighbors and step up support that is provided to them,” Mr. Grandi said last month. “They continue to host millions, and enhanced aid and resettlement places are in order at this difficult time.”

Worldwide, gratitude for host countries has become essential for refugee agencies. More conflicts are protracted and leave displaced people in limbo longer. Over the past three decades, the average period of forced displacement has increased threefold. From Uganda to Colombia, more countries – most of them low- or middle-income – have had to learn to live with refugees.

In January, UNHCR praised Jordan, which is home to more than a million refugees, for issuing a record 62,000 work permits last year to Syrians in the country. This progress, the agency noted, puts Jordan at the forefront of global efforts to give refugees access to decent work.

Since 2018, when the U.N. General Assembly approved the Global Compact on Refugees, many countries have tried to share the burden of hosting refugees and improve pathways for migration. Progress has been slow, which worries experts who predict a rapid rise in refugees caused by climate change in coming decades.

Last September, Mr. Grandi visited Turkey, home to more than 4 million refugees, and praised it for “offering important opportunities for them to achieve their potential.” Such visits are now more common. The gratitude serves as a moral counterpoint to the conflicts that drive people from their homes. It might also nudge more countries to adopt a similar welcoming spirit.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

It’s never too late to conquer fear

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Pauline Brew

The realization that God is ever present brings strength, confidence, and inspiration that empower us to overcome self-doubt.

It’s never too late to conquer fear

Before I began studying Christian Science, I was a very fearful person. Though comfortable with people on a one-to-one basis, I was terrified of doing anything in public. I avoided serving on committees, as I knew I would be tongue-tied. I declined to stand up and deliver a “vote of thanks” speech, and I didn’t even like making announcements. I wished I could speak up at a public meeting, but I couldn’t. I was even timid while driving. I envied people who were fearless and confident.

The Bible says, “Fear hath torment” (I John 4:18). I knew all about that! When I was living in the Middle East, where there was terrorist activity, my grandmother sent me a copy of “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy. I read some of the book and learned that our relation to God as His spiritual reflection keeps us safe, and I was no longer afraid to go out.

Nevertheless, my fears in other areas still needed addressing. I had heard that people had been healed by reading Science and Health, and I knew it had healed me, so I began to study the book in earnest.

This time, it stirred my thought on a deeper level. It dawned on me that there is a spiritual universe that I had not previously been aware of and that I have a place in it. It is where I really live! I am not in reality a timid mortal, but the loved, immortal child of God. My true identity is spiritual and eternally one with God, Spirit, so I am never doing anything alone.

Glimpsing the reality of Spirit’s ever-presence was like waking from a bad dream. Confidence began to well up within me as I learned of my God-given perfection and completeness. Self-doubt started to fade, and my sense of self-worth gradually increased, as I understood that each of us expresses God’s qualities without limitation. So, yes! I could comfortably speak up whenever it seemed appropriate in any situation.

A promise from Science and Health that empowered me was “Whatever is governed by God, is never for an instant deprived of the light and might of intelligence and Life” (p. 215). That meant I could trust that the light of divine intelligence would show me what to say and do, and its might would give me strength to overcome nervousness. So where was there any space for fear?

This was the beginning of the end of this fear. Eventually, I was able to join a speakers’ club and participate in all the assignments. I even won an impromptu speech competition. I worked in a big retail organization, won prizes for selling, and was asked to teach others how to sell. I have introduced speakers on special occasions, served on committees, and organized special functions. I am now a professional speaker, and I love doing it.

It’s never too late to be healed. I was middle-aged before I conquered this fear through prayer, but I have certainly made up for lost time!

Originally published in the Jan. 17, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

First feline

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come again Monday, when our correspondent in Kyiv, Ukraine, tells us how locals are feeling about the possibility of a Russian invasion.