- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Public education, democracy, and the future of America

- ‘Run philosophy’: Why ‘zero COVID’ has young Chinese eyeing emigration

- Searching for hope in the Summit of the Americas

- Indigenous ingenuity: India’s living bridges inspire architects

- Who gets to save the world? ‘Ms. Marvel’ debuts Muslim superhero.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Saudi golf tour: Sportswashing and difficult moral choices?

Put yourself in Dustin Johnson’s size 13 Adidas.

You just joined a new pro golf league, featuring other top golfers including Phil Mickelson. But the league isn’t being lauded for its innovation, or better pay, or for potentially creating more entertaining tournaments for fans.

Instead, many observers are vilifying Mr. Johnson (and others) for being disloyal, greedy, and engaging in sportswashing.

Why? The new LIV Golf Invitational series is financed by Saudi government funds. Critics say this rival to the United States’ PGA Tour is simply a bid to sanitize a regime with a notorious record of human rights abuses.

The first of eight tournaments begins Thursday in the United Kingdom, featuring a big prize purse. Mr. Johnson, a 24-time winner on the PGA Tour, is also reportedly being paid a $125 million “signing bonus.” That’s nearly twice what he made in prize money during his 15-year PGA career. “People can see it for what it is, which is a money grab,” said Irish golfer Rory McIlroy, who has 20 PGA wins.

The PGA threatened to ban anyone who plays in the rival tour. But momentum may be swinging toward the Saudi tour. Mr. Johnson and five other golfers resigned this week from the PGA. Is Mr. Johnson being disloyal to the tour – and the corporate sponsors – that spawned his career? Perhaps. But don’t pro athletes regularly move to better paying teams? Mr. Johnson suggests a higher loyalty. “I chose what’s best for me and my family,” he said Tuesday.

The Saudi sponsorship adds still another layer to the question, in an era when athletes have increasingly been visible taking stands on moral questions.

What would you do if you wore his golf cleats?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Democracy & Education

Public education, democracy, and the future of America

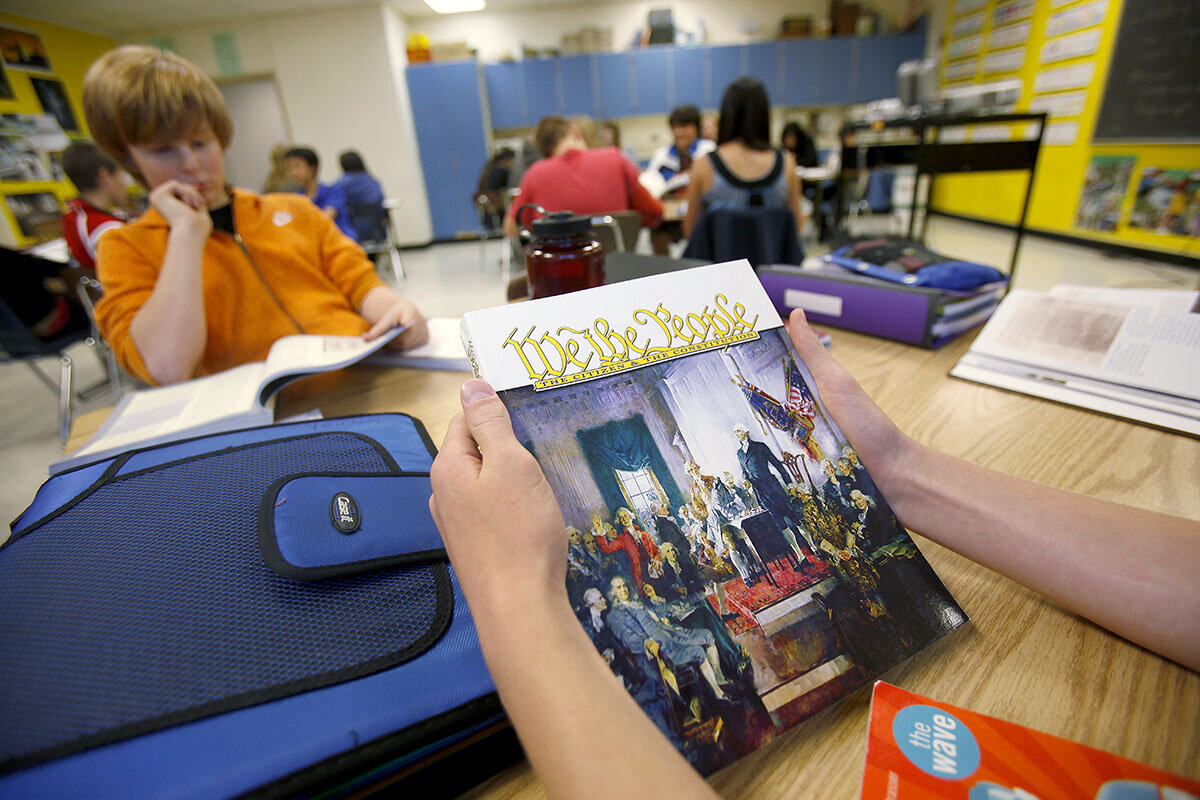

The Founding Fathers considered public education a cornerstone of American democracy – critical to choosing good leaders. Is civics education today being nudged out by partisan politics and economic priorities? The first of a series.

-

Chelsea Sheasley Staff writer

From the beginning of the American republic, some Founding Fathers pushed for the establishment of an institution they thought crucial to the success of democracy: public education.

Self-government would require informed citizens, they felt. Important decisions would be in the hands of farmers and tradesmen, not courts and kings.

Do today’s Americans agree on the importance of common schoolhouses?

Many say they do. Public schools remain the foundation of the education of all but perhaps 13% of the student population. Polls show a majority of citizens generally give high marks to their local schools and teachers.

But the pandemic years, preceded by a decline in the teaching of civics education, have taken a toll on both the quality of the learning and the training of the citizenry. Where does that leave the vision the Founding Fathers had for a democracy dependent on an informed public?

Discussing controversial subjects is a learned skill, says Johns Hopkins Professor Ashley Berner. Teachers can foster an open climate for civil disagreement that does not threaten students’ identity.

“Civic tolerance is a learned behavior,” she says. “We do not come by it naturally.”

Public education, democracy, and the future of America

From the beginning of the American republic, some Founding Fathers pushed for the establishment of an institution they thought crucial to the success of democracy: public education.

Self-government would require informed citizens, they felt. Important decisions would be in the hands of farmers and tradesmen, not courts and kings.

That meant the nation’s youth – the citizens of tomorrow – needed to learn the history and operation of republics. They needed practice disagreeing, debating, and then moving forward together, whether their views won or lost.

The “prospect of [a] permanent union” depended on education in the science of government, said George Washington. “The whole people must take upon themselves the education of the whole people,” said John Adams. “Above all things ... the education of the common people [should] be attended to,” said Thomas Jefferson.

Do today’s Americans agree on the importance of common schoolhouses? Do they hold anymore that public education is fundamental to U.S. democracy?

Many say they do. Polls show a majority of citizens generally give high marks to their local public schools and teachers. The vast majority of American children attend public schools for primary and secondary education.

But the pandemic years have been tough on public schools. Remote learning and physical isolation have taken a toll on test scores and driven many students out of the system altogether. The inequality in outcomes between rich and poor school districts has gotten worse.

Meanwhile, the nation’s political culture wars have elbowed their way into the classroom, as parents and administrators argue over issues dealing with gender, race, and basic U.S. history. The sort of civics education that directly teaches democratic principles and practice is getting squeezed out as curricula focus on preparing students for jobs and college.

The nation’s public schools are at a “turning point,” says Carl Hermanns, clinical associate professor at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, and co-editor of the book “Public Education: Defending a Cornerstone of American Democracy.”

Their status quo has been upended. They can seize the opportunity to improve and reinvent themselves. Or it is possible that the public education system may not survive in its present form.

“If it atomizes and ... public schools as we know them don’t exist anymore, what will happen is an open question,” says Professor Hermanns.

“One of the two foundational elements”

Citizens could certainly participate in democracy without public education. But public schools in the United States remain the foundation of the education of all but perhaps 13% of the student population, who attend private school or are home-schooled. And study after study has shown that the more education people have, the more they vote, and the more they participate in a nation’s political life.

There are some indications that year by year, education simply increases the general feeling that voting is a social and civic norm, the right thing to do.

“American public education is one of the two foundational elements of our democracy. The other is the ballot itself,” says Derek W. Black, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and author of “Schoolhouse Burning: Public Education and the Assault on American Democracy.”

At the time of the American Revolution, elites remained nervous about opening up participation in choosing leaders to the common people, fearful that their participation would lead to mob rule and the rise of hucksters.

To many of the founders, schooling was the answer. Intelligent exercise of the franchise would hold democracy together.

“They believed that there was a common good, and that they’d find the common good together, through education,” says Professor Black.

That doesn’t mean public education was widespread in America from 1787 on. Despite the visions of Adams, Jefferson, and others, education in the early years of the nation was mostly limited to well-off white men – as was voting.

There are a lot of startup costs in the establishment of a school system, and many attempts to expand schooling foundered on the expense. In 1817, Jefferson proposed in his home state of Virginia to establish taxpayer-supported schools in every 5 or so square miles, teaching classical, European, and American history, as well as reading and arithmetic.

Jefferson’s effort did not pass. It took centuries for the vision of widespread public schools to be fully realized. Like voting rights, school rights grew step by step. At first limited to well-off white men, they expanded into lower incomes, other races, and women – sometimes sliding back, but by the civil rights era of the 1960s promised to all.

“You’ve got to have everybody educated from all walks of life in order for this [democracy] to work,” says William Mathis, senior policy adviser at the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado.

Shift from civics to job preparation

Civics education was an integral part of most public school curricula in the middle to later years of the 20th century. Teachers had the time and flexibility to dwell on more than just the basics of U.S. history and the structure of democratic government.

Yet the teaching of those subjects has “eroded” over the last 50 years, says the 2021 report from Educating for American Democracy (EAD), a diverse group of educators and scholars, partially funded by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Endowment for the Humanities, that is worried about this decline.

Across that same five-decade time period, partisan and philosophical polarization in the U.S. has increased, says the group. Social media and partisan news outlets have pumped dangerous amounts of political misinformation into the nation’s discourse. The public in essence may have lost the thread, with the majority functionally illiterate about our constitutional principles, according to the EAD report.

To this point, a 2017 survey by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only about 25% of Americans could correctly name all three branches of the U.S. government. One-third couldn’t name any branch of the government at all. Four years later, the Annenberg survey found that the number of Americans who could name all three branches had risen to 56%, and that 20% couldn’t name any branch at all.

“The relative neglect of civic education in the past half-century is one important cause of our civic and political dysfunction,” concludes the EAD report.

Why the slide in civics? Education experts say U.S. schools have been reoriented to focus on getting students ready to participate in the economy.

Thus, the rise of STEM – science, technology, engineering, and math – education. The Sputnik panic of 1957, when the nation was gripped by fear it was falling behind the Soviet Union in technical skills, has never completely abated. Studies still bemoan how U.S. children lag in math and science. Parents see STEM programs as gateways for better opportunity for their kids.

There is greater focus today on getting secondary students ready for college. Test-based educational reform has narrowed the focus of schools to narrower lesson plans focused on math and reading, lest their scores slide.

Amid all these pressures social studies, history, and other humanities topics have all become lower priorities. Government studies has often been de-emphasized.

“We have to remind ourselves over and over again that the whole point of compulsory free public education was to make citizens, was to produce people capable of self-government, and I think we forgot that because we talk [a lot about] the other two C’s ... career and college,” says Eric Liu, executive director of the Citizenship and American Identity Program at the Aspen Institute, and CEO and co-founder of Citizen University.

“Coming together in a shared space”

But public schools don’t just teach democratic habits through instruction, say their proponents. By their very design, American school systems are intended to model democracy, throwing together children from many walks of life in a single place for a common endeavor. They are supposed to learn people’s differences and other points of view.

“It’s a place where people from different backgrounds – and I mean everything from race and gender to religion and economics and general ideologies and different values – where people are all coming together in a shared space ... to see and value what it means to be an American,” says Sarah Stitzlein, professor of education at the University of Cincinnati and co-editor of the journal Democracy & Education.

But this communal aspect of public schools has faced challenges in recent years. To begin with, the pandemic too often physically isolated students, keeping them from the interactions that help them learn about each other. It drove down the overall number of students as well. About 1.3 million students have left public school systems since the pandemic began in 2020, according to one national survey. All but a handful of states have experienced enrollment declines over that period.

In addition, the culture wars have come for the schools, with state legislators and governors moving to control what can and can’t be taught about America’s racial history and sexism. Since January of last year, 42 states have introduced bills or taken other action that would circumscribe teaching on these sensitive subjects, according to a database maintained by Education Week. Seventeen of these states have imposed their bans.

This all takes place in the context of continued pressure from advocates of sweeping change in the way the nation educates its children to de-emphasize traditional public schools and greatly expand the use of charter and private schools.

Such radical decentralization would greatly affect the democracy-building mission of the public schools, say experts who support the traditional system. Among other things, it might expose students to less social and cultural diversity.

“I think the idea of ‘go find a better school that better matches your views to tone down the culture war’ is a huge danger to our society and to democracy,” says Dr. Hermanns.

But public schools really aren’t civic melting pots, say some right-leaning education analysts. They tend to be monolithic, segregated racially and socially, because they reflect the demographics of American communities.

And public schools are not alone in their ability to teach fundamentals of democratic involvement, says Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and co-editor of “How To Educate an American: The Conservative Vision for Tomorrow’s Schools.”

There’s evidence that private schools and charters “take their civic responsibility just as seriously as traditional public schools,” he says.

Needed: a shared conversation

More time devoted to teaching civics, social studies, and U.S. and world history. More emphasis on structured discussions and debate.

Those are the basic moves that scholars of democracy and education support to help strengthen schools’ role in developing citizens.

As to what specifically should be taught, there is far less consensus.

The bipartisan EAD effort does not lay out a specific curriculum. Instead it identifies categories that students should explore in discussions, from America’s role in the world in its history, to the nation’s social and institutional transformation over time, and the basics of civic participation.

“Fraught though the terrain is, America urgently needs a shared, national conversation about what is most important to teach in American history and civics, how to teach it, and above all, why,” says the EAD report.

One tool that might help students build their civic capacity is a sustained practice with meaningful disagreement in the classroom, says Ashley Berner, an associate professor and director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy.

Discussing controversial subjects is a learned skill, says Professor Berner. Teachers can foster an open climate for civil disagreement that does not threaten students’ identity.

“Civic tolerance is a learned behavior. We do not come by it naturally,” she says.

Professor Berner also favors pluralist educational systems, in which government funds a wide variety of schools, including religious schools, but maintains control over teaching standards, curriculum, and assessments.

Such systems “are common in democracies around the world,” she says.

In the United States, education is not a federal right. Such a right is enshrined in all 50 state constitutions, but not in the U.S. Constitution.

The nation should consider establishing such a right through the courts, Congress, or a constitutional amendment, says Kimberly Robinson, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law and editor of “A Federal Right to Education: Fundamental Questions for Our Democracy.”

America really has two educational systems, says Professor Robinson: one for upper- and middle-class students that works well, and one for low-income, rural, and many Black and Hispanic students that works much less well.

A federal right could provide leverage and attention to begin to counter that disparity.

“It’s important,” says Professor Robinson, “because the more educated a child is, the more likely they are to vote when they become an adult, and they are more likely to be engaged civically not just in elections, but in community service and other avenues and opportunities that help make our communities and our democracy stronger.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include the most recent survey findings from the Annenberg Public Policy Center, and to clarify that the percentage of Americans attending public schools refers to the student population, rather than the entire population.

This story is the first in a four-part series:

Part 1: Do Americans agree on the importance of common schoolhouses? Do they still hold that public education is fundamental to democracy?

Part 2: How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

Part 4: How has parental participation in public schools shaped U.S. education?

‘Run philosophy’: Why ‘zero COVID’ has young Chinese eyeing emigration

A perspective shift: Our reporter looks at how the pandemic lockdowns in Shanghai may have altered Chinese confidence in Beijing to provide security in exchange for less freedom.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Scenes of mass exodus have played out across Shanghai in recent weeks, as authorities work to contain the country’s largest COVID-19 outbreak. On several occasions, people lined up for at least a mile on the access road to Hongqiao Railway Station, bedraggled refugees out of place against the backdrop of manicured boulevards and futuristic high rises.

For many urban, educated millennials, the lockdowns and quarantines imposed in Shanghai and dozens of cities nationwide have been a traumatic, paradigm-shifting ordeal that has shaken their sense of security. Even since Shanghai mostly reopened June 1, new cases have led authorities to impose fresh lockdowns, creating concerns about an endless cycle of easing and restrictions. Young Chinese have fled Shanghai in droves, and now, some are considering leaving the country altogether.

On social media, discussions about emigration are surging. Chinese netizens created a word for it – runxue, or “run philosophy.”

“It reflects a kind of escapism psychology – people choosing to run away from this place,” says Chen Daoyin, a political scientist and former associate professor at the Shanghai University of Political Science and Law. “The middle-class group expected a decent life [in China]. ... Before they exchanged freedom for security, but now they have neither freedom nor safety.”

‘Run philosophy’: Why ‘zero COVID’ has young Chinese eyeing emigration

Through deserted Shanghai streets, some people silently pedaled bicycles, dragging roller bags with one hand or balancing luggage precariously on front wheels. Others fled the city’s lockdown on foot, wearing full hazmat suits and carrying possessions stuffed into plastic bags. They lined up for at least a mile on the access road to Hongqiao Railway Station, bedraggled refugees out of place against the backdrop of manicured boulevards and futuristic high rises. Among the crowd was Carol, a writer.

She recalls surveying the scene in May, shocked by how the ultramodern, cosmopolitan city she’d viewed as a splendid castle had transformed overnight into a place of mass deprivation.

“After this experience in Shanghai, everyone feels we aren’t living in a palace after all, but in a mud-brick house with a thatched roof,” says Carol, who spent more than two months confined to her apartment block with limited food during the country’s biggest COVID-19 outbreak. A Chinese citizen, she asked to use only her English name to protect her identity.

Similar scenes of exodus have played out across the city of 25 million people in recent days and weeks. For many urban, educated millennials like Carol, the lockdowns and quarantines imposed in Shanghai and dozens of cities nationwide have been a traumatic, paradigm-shifting ordeal that has shaken their sense of security. People have fled Shanghai in droves, and now some are considering leaving China altogether.

“The middle-class group expected a decent life,” says Chen Daoyin, a political scientist and former associate professor at the Shanghai University of Political Science and Law. “Before they exchanged freedom for security, but now they have neither freedom nor safety.”

What struck Carol about the lockdown in Shanghai was that no one could protect themselves. “This thing is universal – your freedom of residence and freedom of travel will be restricted. ... All the people are suffering,” she says from her hotel room in a neighboring province. No matter how much money you have or how big your house is, she adds, “you may get a knock on the door and be taken away in the middle of the night.”

Concerned that China’s strict zero-COVID-19 controls will further encroach on basic freedoms and lead to economic and social stagnation, Carol and many of her peers are exploring contingency plans to move overseas.

Carol, who has never lived abroad before, plans to work harder and earn more. “If I have enough money,” she says, “I will go.”

Running away

When Joanna returned to Shanghai three years ago after graduating from college in the United States, she expected to live in China for the rest of her life. A two-month lockdown changed her mind.

“This exceeded my worst predictions,” says the Shanghai-based media worker, asking to withhold her last name to protect her identity. Her goal now is to secure permanent residency in another country, while keeping her Chinese citizenship. “I want that option,” she says, to avoid the “terrifying” feeling that she is trapped in China.

China has allowed millions of its youth to study abroad in recent decades, but the majority have returned home, anticipating they will have better career opportunities here. Yet as the stringent COVID-19 policy exacts a rising economic and social toll, including high urban unemployment, some returned students like Joanna are again looking outward.

Joanna’s main concern is that the zero-COVID-19 policy, while it has succeeded in keeping cases and deaths in China low, is no longer economically feasible. Official figures show China’s economy contracting in recent months, with retail sales and industrial production declining. “If you keep suppressing people’s morale, everyone loses their desire to consume,” she says.

Even since Shanghai mostly reopened June 1, new outbreaks have led authorities to impose fresh lockdowns, creating concerns about an endless cycle of easing and restrictions. More than 1 million people remain confined at home or in quarantine facilities.

Meanwhile, online discussions about “running away from China” have surged. Chinese netizens created a word for it – runxue, or “run philosophy,” a play on words using a Chinese character that sounds like “run” in English.

“It reflects a kind of escapism psychology – people choosing to run away from this place,” says Dr. Chen.

On WeChat, China’s top social media app, Chinese users searched for the term emigration more than 100 million times on a single day in May, according to data released by the company. Emigration has also been a popular topic on China’s Twitter-like social media platform, Weibo, and millions have viewed a question about “run philosophy” on Zhihu, China’s version of Quora.

Users of GitHub, the world’s largest open-source platform for software, set up a repository that is gathering detailed strategies and tips on how to emigrate from China.

“To ‘run’ is a kind of risk aversion,” says Joanna. “Many people are thinking about it. They may not have pulled the trigger, but if things continue to go badly, I believe many people will take practical actions.”

Exit strategy

Allen Ai, a Chinese accounting student in Italy, left China a year ago after losing his job during the pandemic. He’s now fielding messages from contacts back home asking him for advice on moving abroad.

Yet even as the COVID-19 restrictions are pushing some young people to try to emigrate, Chinese authorities are imposing tighter controls on those attempting to leave.

Citing pandemic prevention requirements, the National Immigration Administration announced last month that it will “strictly restrict non-essential exit activities of Chinese citizens.” Last year, it said it would suspend issuing passports to people with “non-urgent” reasons for leaving the country.

China is unlikely to lift such overseas travel restrictions as long as it maintains the zero-COVID-19 policy, which is currently here to stay, experts say.

Ma Xiaowei, head of the National Health Commission, wrote in the Communist Party publication Qiushi on May 16 that China is planning to set up large numbers of booths for regular COVID-19 testing in all provincial capitals and cities with more than 10 million people, while also creating permanent quarantine centers. The goal is to maintain COVID-19 prevention while reducing disruptions to normal life – an approach that showed better results in Beijing recently.

“Mass testing, makeshift shelters, and green code for travel – this may be the status in China for the next three-to-five, or five-to-10 years,” Dr. Chen says, referring to the health code system that tracks each individual’s COVID-19 risk status.

As for Mr. Ai, he’s seeking permanent resident status in Italy, where he expects to have more opportunities. “I think I made a correct decision,” he says. “If I stay in China, I don’t know what I can do.”

Essay

Searching for hope in the Summit of the Americas

Next up: a first-person sense of history and a window on how leaders define freedom and build relationships from our reporter, who has attended many of these summits over nearly three decades.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

I have attended six of the past eight Summits of the Americas – the ninth is being hosted by President Joe Biden in Los Angeles this week – and at some point I concluded that the summits peaked early, perhaps even at the inaugural gathering in Miami in 1994.

Miami had crackled with anticipation for where the summit process could take the hemisphere. President Bill Clinton led the proceedings, which touted a free-trade area “from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.”

My inaugural post-summit story’s headline: “Task for Americas Leaders: Keep Spirit of Miami Summit Alive.”

But with only a few exceptions, that task went unfulfilled. When the Trump administration, which revived talk of the Monroe Doctrine, sent Vice President Mike Pence to Lima in 2018, his reception was frosty.

Attending the LA summit is Chile’s young socialist president, Gabriel Boric, who has already said he plans to let President Biden know that the exclusion of Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua over their lack of democracy and poor human rights records was a “mistake.” One measure of the summit’s ultimate success may be whether Mr. Biden manages to hit it off with any of the hemisphere’s leaders. I will be watching in particular for any signs of rapport between Mr. Biden and Mr. Boric.

Searching for hope in the Summit of the Americas

It was the moment that those of us covering the Fifth Summit of the Americas were waiting for.

Just months into his presidency in April 2009, Barack Obama was signaling a new kind of U.S. leadership in the Western Hemisphere by meeting and chatting with regional socialist bad boy Hugo Chávez at the gathering in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.

The two leaders shook hands and smiled, and Mr. Chávez took the opportunity to slip the American a copy of Eduardo Galeano’s classic tome on imperialism in the region, “The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent.”

Later an unfazed President Obama would tell us that rather than wagging a finger at Mr. Chávez over the direction he was taking Venezuela, he had simply thanked him for the book. “He knows I’m a reader,” he said.

Indeed, two Americas summits later – in Panama in April 2015 – Mr. Obama would break the taboo dating from the first summit in Miami in 1994 and acquiesce to the regional clamor for communist Cuba to be allowed to attend a gathering whose invitation list is based on democratic governance and a free-market economy.

Cuba had neither, but that did not stop Mr. Obama from smiling for the press cameras as he shook Cuban leader Raúl Castro’s hand in Panama City.

Those are the moments we journalists focused on at these hemispheric summits, and for two reasons.

First, because they helped illustrate how U.S. leadership and interest in the Americas was evolving. But second, because the truth was that – especially by the time Mr. Obama was in the White House, but even as early as the post-9/11 first-term years of George W. Bush – not much else was happening at the meetings.

I have attended six of the past eight Summits of the Americas – the ninth is being hosted by President Joe Biden in Los Angeles this week – and at some point I came to the conclusion that the SOTAs, as they are called in diplo speak, peaked early.

Indeed, it may not be going too far to say that the summits reached their high point with the inaugural Miami gathering.

The Spirit of Miami

Miami had crackled with excitement and anticipation for where the summit process could take the hemisphere. President Bill Clinton led the proceedings, which focused on the goal of creating a free-trade area “from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.”

With South America’s military dictatorships having been replaced with democratically elected leaders, and the region’s guerrilla wars largely quieted (Colombia remaining an exception), the summit could proceed with all countries from Canada to Argentina and Chile in attendance – save for Cuba.

The summit even played a role in transforming Miami from a fading pastel beach town to a hub of Latin American enterprise, as political scientist Eduardo Gamarra of Florida International University used to relish telling me.

My curtain-raiser on Miami carried the headline, “The Bonding Of a Continent,” and featured this lead quote from then-Costa Rican President José María Figueres Olsen: “If just 10 years ago someone had said today we would have a continent of democratically elected governments promoting their economic development through free trade, we would have said it was not possible.”

My post-summit story’s headline read: “Task for Americas Leaders: Keep Spirit of Miami Summit Alive.”

But with only a few exceptions, that task went unfulfilled, and the “spirit of Miami” went cold – the victim of 9/11 and the United States’ focus on a new national security threat; growing opposition to a hemispheric free-trade accord; and rising public dissatisfaction with democracy’s ability to deliver.

Leaders assembled at the 2001 summit in Quebec City did direct their diplomats to come up with an Inter-American Democratic Charter, which would strengthen the region’s commitment to democratic governance. The document was adopted at an Organization of American States special session – on Sept. 11, 2001.

But beyond that, most subsequent summits were marked more by dissension and public rejection than unity.

Two visions of freedom

At Mar de Plata, Argentina, in 2005, large anti-globalization and anti-free-trade demonstrations were the main event outside, while inside a growing list of countries was now balking at the Miami commitment to create a hemispheric free-trade area.

Indeed, some demonstrators I spoke with on the streets assured me that the bonfires they set symbolized the FTA going up in smoke. They turned out to be right.

The Mar de Plata summit was also an opportunity for me to contrast two visions of freedom as embodied by two of the hemisphere’s controversial figures: President Bush, who two years before the summit had launched the Iraq war ostensibly to bring freedom to the Iraqi people and the wider Middle East; and Argentine native son Ernesto “Che” Guevara, champion of freedom from imperialist domination.

Mr. Bush touted freedom of the individual, I wrote in a pre-summit story from Buenos Aires, while Che championed the collective freedom of socialism.

And in Argentina, where average folks I interviewed on the street still spoke in terms of “our Che,” Mr. Bush didn’t have a chance.

President Obama, who normalized relations with Cuba and shook hands with everybody, sat better with people across Latin America, and his appearances at Americas summits attested to that. Still, he could never shake the deepening conviction among many in the region that, on the whole, the hemisphere just didn’t matter much to Washington anymore.

That image of an increasingly benign but distracted hegemon would come crashing down with President Donald Trump.

Mr. Trump’s first secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, alarmed the region by resurrecting mention of the 19th-century Monroe Doctrine to assert Washington’s primacy in the hemisphere – only now with Chinese and Russian meddling in the region in mind rather than European powers.

Before long, national security adviser John Bolton would be imploring Mr. Trump to “reassert the Monroe Doctrine,” while the president would further alarm the region by threatening to send the U.S. military into Venezuela and to the U.S.-Mexico border – a sure sign he held to the Monroe premise that the U.S. had every right to intervene in its sphere of influence.

That position was hardly a winner across Latin America – to the point that when the Summit of the Americas rolled around in Peru in 2018, Mr. Trump did not even bother to attend. Vice President Mike Pence was sent instead, but his reception was frosty – signaling the depths to which U.S. relations with the region had plunged.

Ironically, it was the Trump administration that agreed to have the U.S. play host this year.

The A team

The Biden administration seemed to get off to a slow and rocky start in its summit planning, but the White House is signaling the gathering’s importance by sending the A team to LA.

Attending with Mr. Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris will focus on migration issues, while Secretary of State Antony Blinken will address press freedom and meet with young entrepreneurs from across the hemisphere. USAID Administrator Samantha Power will take on regional food insecurity and women’s empowerment.

One measure of the summit’s ultimate success may be whether President Biden, who is known to thrive on personal relationships, manages to hit it off with any of the hemisphere’s leaders.

I will be watching in particular for any signs of rapport established between Mr. Biden, with his years of experience in the region, and Chile’s new and young socialist president, Gabriel Boric.

Mr. Boric has already said he plans to let Mr. Biden know that his exclusion of Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua from the summit over those countries’ lack of democracy and poor human rights records was a “mistake.”

But I’m hoping the bearded former student protest leader also presents the U.S. president with a book, say a collection of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s work. That would give journalists something insightful to write about.

Howard LaFranchi is the Monitor’s longtime diplomatic correspondent and a former Latin America bureau chief.

Indigenous ingenuity: India’s living bridges inspire architects

India’s living bridges, made from tree roots, aren’t just a natural wonder; they also offer a unique mental framework for solving engineering and architectural problems.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Anne Pinto-Rodrigues Contributor

In India’s northeastern state of Meghalaya, one of the wettest places on the planet, people rely on ancient bridges to cross the region’s many streams and rivers. But these aren’t typical overpasses – the bridges are alive.

For hundreds of years, the Khasis of Meghalaya have manipulated the aerial roots of the rubber fig tree to build sturdy bridges, known in the Khasi language as jingkieng jri. There are at least 150 such bridges in Meghalaya today, according to Morningstar Khongthaw, who works to preserve and educate the public about the community’s architectural traditions.

The jingkieng jri are not only a big tourist draw, but also an important proof of concept for engineers and designers interested in practicing living architecture. Integrating plants into architectural design lessens the need for harmful construction materials and promotes biodiversity, but it can also take generations to test and develop the right building methods. Bioengineers from around the world are studying the living root bridges in the hopes of applying aspects of the Khasi tradition to projects in their own countries.

“The Khasis have a brilliant understanding of architectural engineering, totally different from the western way,” says Ferdinand Ludwig, professor at the Technical University of Munich, adding that their traditions could offer “new solutions for [greening] construction.”

Indigenous ingenuity: India’s living bridges inspire architects

Covered with thick subtropical forests and streaked with streams and rivers, the hilly state of Meghalaya in India’s northeastern corner is one of the wettest places on the planet. During the monsoon season, torrential rains turn docile rivers into raging waterways, and people rely on centuries-old bridges to access farms, schools, and markets.

But these aren’t typical overpasses made of wood or steel – the bridges are alive.

For hundreds of years, the Khasis of Meghalaya have manipulated the aerial roots of the rubber fig tree (Ficus elastica) to build sturdy bridges, known in the Khasi language as jingkieng jri. There are at least 150 such bridges in Meghalaya, according to Morningstar Khongthaw, who works to preserve and educate the public about the community’s architectural traditions. The figure includes the famous double-decker living root bridge of Nongriat village, which locals estimate is about 250 years old. Mr. Khongthaw’s village, Rangthylliang, has 20 living root bridges. “The oldest one is about 700 years old,” he says, with great pride.

Today, the jingkieng jri are not only a big tourist draw, but also an important proof of concept for engineers and designers interested in practicing living architecture. Integrating plants into architectural design lessens the need for harmful construction materials and promotes biodiversity, but it can also take generations to test and develop the right building methods. Bioengineers from around the world are studying the living root bridges in the hopes of applying aspects of the Khasi tradition to projects in their own countries.

“The Khasis have a brilliant understanding of architectural engineering, totally different from the western way,” says Ferdinand Ludwig, professor of green technologies in landscape architecture at the Technical University of Munich. “Their way of thinking forms the conceptual base of a new way of architecture and engineering that we urgently need to cope with climate change.”

Ancient bioengineering

“There are different ways of designing, building, and growing a living root bridge,” says Mr. Khongthaw. The most popular model of construction, and the fastest, involves the creation of a bamboo framework, over which the roots of a nearby rubber fig tree are pulled and intertwined, until the roots reach the opposite bank. The bamboo framework itself serves as a temporary bridge while the living root structure takes shape. Over time, the bamboo rots away while the roots grow and merge together, making the structure sturdier and more stable.

The time required to reach the first functional stage – when the bridge is strong enough to hold about 500 pounds, or roughly three people with loaded baskets – depends on the required length of the bridge. Mr. Khongthaw says a bridge crossing a stream would be about the length of a school bus, and take nearly 20 years to become functional, whereas a bridge across a river would take 70-80 years. In places where there are no rubber fig trees nearby, villagers must first plant a sapling on the river bank and wait 10-15 years for the aerial roots to appear before building the bamboo framework.

In all stages of their development, the bridges require regular maintenance. This happens in monsoon season when the roots are more pliable. “Everyone in my village takes part in maintaining the bridges,” says Mr. Khongthaw. “Whoever crosses the bridge, spends five or 10 minutes working on the roots to make the structure stronger.”

In the past, the work of constructing and maintaining bridges was done by men. But that is changing. “Nowadays, women are also involved,” says Mr. Khongthaw.

In addition to bridges, the Khasis construct cliffside ladders, tree platforms, swings, and tunnels using traditional techniques passed down orally from one generation to the next. Now, the Khasis are sharing their knowledge with the rest of the world.

Global applications

In Germany, Professor Ludwig has been studying examples of living architecture from around the world for nearly two decades. He has designed and overseen the construction of several structures that integrate plants, including a footbridge that uses living willow plants as the sole supports.

Professor Ludwig first learned of the living root bridges of Meghalaya in 2009, via a documentary, and was struck by the Khasi approach to building. “They do not prescribe the structure itself. They only prescribe the aim,” he says. “They want to go from A to B in a safe and comfortable way. They plant a tree and manipulate the growth of the roots in a direction that is beneficial to them.”

One of his students at the Technical University of Munich, Wilfrid Middleton, is studying Meghalaya’s living root bridges as an example of regenerative design – an increasingly popular concept wherein structures are not just sustainable (built with minimal and efficient use of resources) but they also replenish the resources required for their functioning and enrich their surroundings, thus having a net-positive effect on the environment. In cities, living structures like the footbridge designed by Professor Ludwig can help sequester carbon, create a cooling effect, and provide a habitat to birds and other urban wildlife. Manipulating ficus plants or comparable species could open up “new solutions for [greening] construction in densely populated urban areas,” Professor Ludwig adds.

Mr. Middleton has visited 70 jingkieng jri so far, and with the consent of the village elders, he photographs the bridges to create precise 3D models. “Each year, as the bridge grows and changes, we are able to capture its incredibly complex structure,” he says. “We are trying to learn from the Khasis.”

Preserving Meghalaya’s bridges

While there is increasing international appreciation of the living root bridges, back in Meghalaya, Mr. Khongthaw says many villagers aspire for a modern lifestyle, complete with concrete houses and bridges. Worried that traditional Khasi knowledge may feel irrelevant to younger generations, Mr. Khongthaw founded the Living Bridge Initiative in 2016, with the objective of preserving, protecting, and increasing the number of living root bridges. He regularly visits educational institutions to speak about his work.

“These bridges, which our elders have worked on for so many years, are being forgotten,” he says. “I wanted to start something to recognize their efforts.”

Mr. Khongthaw has also started a sapling center to address the shortage of rubber fig saplings, which are not easy to find in the forest. The biggest threat to these ancient bridges, however, are the development projects in their vicinity.

Byron Nongbri runs a homestay with his wife, near the famous double-decker bridge in Nongriat village. In 2016, he participated in stopping a road project that would have led to a flood of tourists in the area. Now he is worried about a limestone mining project underway barely 3 miles from his village. “It will surely harm my paradise,” says the father of five.

Meanwhile, Mr. Khongthaw finds hope in building new bridges, and honoring the wisdom and ingenuity of his ancestors. He was recently involved with the construction of seven bamboo bridges, each of which will be used as the framework for a new living root bridge, to be shaped and maintained by future generations.

“Our knowledge should be recognized not only in Meghalaya but everywhere,” he says.

Television

Who gets to save the world? ‘Ms. Marvel’ debuts Muslim superhero.

If movies are a mirror on society, Hollywood is just catching up with societal diversity. The latest Marvel character reflects a heroism trend and, as one scholar tells us, “a type of ethical and moral expression of equality.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Tyler Bey Special contributor

When “Ms. Marvel” debuts on Disney+ this week, it will bring the first Muslim superhero, teen Kamala Khan, to millions of viewers.

Lead actor Iman Vellani was an ardent fan of the “Ms. Marvel” comic books that the TV series is based on when she was growing up. Now she has become the hero she idolizes.

For underrepresented groups, seeing themselves on the page and on the screen can have an empowering effect. Just ask Ms. Vellani. But until recently, the most well-known on-screen heroes in capes, spandex, and armor have largely been white.

Now, Hollywood is starting to break the mold. The film industry is belatedly realizing that there’s an audience demand for iconic characters who reflect today’s multicultural world. One yardstick of how much things have changed: J.J. Abrams is producing a Black Superman movie written by journalist and author Ta-Nehisi Coates.

“It does matter that people who are at the margins see themselves as being participants in the center of building and creating and being heroic in this world,” says Adilifu Nama, author of “Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes.” “It gives [audiences] an opportunity to at least challenge their ... notions of what diversity can be.”

Who gets to save the world? ‘Ms. Marvel’ debuts Muslim superhero.

“Ms. Marvel,” which debuts Wednesday on Disney+, features an unconventional superhero: a teenage Muslim girl.

Kamala Khan is a New Jersey high school student whose traditional, Pakistan-born parents worry that she doesn’t have a direction in life. Kamala is, however, passionate about one hobby: She’s a fangirl of The Avengers – especially Captain Marvel. One day, while furtively attending a comic book convention dressed as her idol, Kamala gains powers that transform her into a real superhero.

The lead actor in “Ms. Marvel,” Iman Vellani, has a backstory that’s as meta as that of the origin story that unfolds on screen. Growing up, Ms. Vellani was an ardent fan of the “Ms. Marvel” comic books that the TV series is based on. She only auditioned for the role because, as she told The Hollywood Reporter, “my 10-year-old self is going to hate me if I don’t do it.” Now she, too, has become the hero she idolizes.

When underrepresented groups see themselves on the page and on the screen, it can have an empowering effect. Just ask Ms. Vellani. But until recently, the most well-known on-screen heroes in capes, spandex, and armor have largely been white. (Well, perhaps not the Hulk.)

Now, Hollywood is starting to break the mold. A number of upcoming movies include people of color with superpowers. The film industry is belatedly realizing that there’s an audience demand for iconic characters who reflect today’s multicultural society. One yardstick of how much things have changed: J.J. Abrams is producing a Black Superman movie written by journalist and author Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Credit comic books for being first to create diverse superheroes – including LGBTQ characters – who can now be adapted to the screen. Advocates for cultural pluralism in storytelling say that diverse superheroes can offer valuable insights into other people’s experiences. But, some add, the traits that make superheroes universally relatable are the underlying flaws, moral conundrums, and insecurities that speak to all of us.

“It does matter that people who are at the margins see themselves as being participants in the center of building and creating and being heroic in this world,” says Adilifu Nama, author of “Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes.” “It gives [audiences] an opportunity to at least challenge their ... notions of what diversity can be, should be, and they can take actual joy in the diversity that they bear witness to. It doesn’t always have to be an imposition.”

In 2018, “Black Panther” disproved Hollywood’s conventional wisdom that a Black superhero film wouldn’t have worldwide appeal. Now, many more like it are in the works. The success of “Black Panther” opened the door for Marvel movies with Asian leads, including “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” and “Eternals.” Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny will soon star as Marvel’s first Latino superhero in the movie “El Muerto.” And this fall, the formidable biceps of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson will stretch the spandex supersuit of the DC Comics character Black Adam.

In Hollywood, money speaks loudest. A UCLA study of English-language movies released in 2021 found that people of color had a significant impact on box-office revenue, especially on opening weekends. But that’s not the sole reason the film industry is trying to increase diversity in front of, and behind, the camera.

“Hollywood executives don’t want to be embarrassed anymore,” says Tim Gray, awards editor of features and senior vice president for Variety. “When #OscarsSoWhite started that movement, I think it was January 2015 when the Oscar nominations came out, it was like a wake-up call. It’s like, ‘Look, people are watching you and people are going to hold you accountable.’”

When it comes to diversity, comic books have often been out front. After all, in the United States, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created the first African superhero, Black Panther, back in 1966. Other Black icons such as The Falcon, Blade, and Luke Cage followed in the Marvel universe soon afterward.

“The consumer now has to deal with a new type of Black person – a Black person that can fly, not a Black person that says, ‘Yessir, boss,’” says Dr. Nama, who is a professor of African American studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. “They are symbols of racial reconciliation. Because these are Black superheroes who ... do not fight to save just one particular racial or ethnic group. They are here to serve and save humanity. So they speak to a type of ethical and moral expression of equality.”

Kwanza Osajyefo, a writer who has worked at Marvel and DC Comics, independently released an even more radical comic story. “Black” imagines a society where only Black people have superpowers. A highly anticipated sequel, “White,” released in 2021, was inspired by the racial tension of Trump-era politics.

Mr. Osajyefo told the Monitor that new and refreshing stories are emerging from artists within the uplifting and tightknit Black comic community. He hopes that the future of Black storytelling is one that includes youth, especially those underserved in economically unstable communities.

In recent years, famous characters in print have also been recast as different racial identities – sometimes as alternate versions of superheroes. For example, the alter ego of Silk, who has powers similar to Spider-Man’s, is a Korean American teenager named Cindy Moon. Amadeus Cho, an Asian nerd, transforms into the Hulk-like Brawn. Riri Williams, a genius 15-year-old Black teen, makes her own version of an Iron Man suit to become Ironheart. Riri will make her big-screen debut in November in “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.”

New iterations of icons such as Green Lantern, Batwoman, The Flash, and Superman: Son of Kal-El have also come out as gay, bisexual, nonbinary.

Susan Kirtley, director of comics studies at Portland State University in Oregon, says that some fans, attached to the characters they grew up with, express racism, sexism, and homophobia about revisions to characters. “There was a lot of pushback when a female picked up the hammer and became the new Thor. ... There’s a couple of great scenes [in the comics] where the new female Thor is fighting against a character called Absorbing Man. It was really delightfully on the nose because Absorbing Man was acting like one of the [internet] trolls,” she says.

The inclusion of previously underrepresented identities in comic books reflects how the industry has changed. An increasing number of the writers and illustrators behind these creations are female, LGBTQ, and people of color. Sometimes, their creations are meant to provoke political or cultural conversation. In a 2014 comic, the Falcon inherited the role of Captain America. That storyline carried over into the movie “Avengers: Endgame” and the subsequent TV series “The Falcon and the Winter Soldier.”

On the small screen, TV networks and streamers have experimented more with appealing to niche audiences – with mixed results. The Ava DuVernay-helmed “Naomi” on the CW, about a Black teen, lasted just one season this past year. Netflix’s “Raising Dion,” from Michael B. Jordan (“Black Panther”), about a mom raising a Black child with superpowers, was just canceled after two seasons.

“Ms. Marvel” is an example of a story that reflects its roots. The character lives in a New Jersey neighborhood similar to the one that co-creator Sana Amanat, a Pakistani American, grew up in. Ms. Amanat and writer G. Willow Wilson wanted to challenge stereotypes of Muslims and also tell a story about someone defying labels and categories to find their true self. As if to underscore that Kamala is no conventional superhero, her costume features a silk scarf – reflecting her Pakistani heritage – rather than a cape.

The universality of “Ms. Marvel” stems from the fact that Kamala’s story isn’t a generic tale of how teens often clash with their parents, says Hussein Rashid, co-editor of “Ms. Marvel’s America: No Normal,” a book of essays about the comic book character’s impact on culture. It’s the specificity of her story as someone with a Pakistani heritage that offers a realism that draws us in – and also reveals that some broader human experiences are common to every race and ethnicity, even if the particular manifestations are different.

“This is the power of story,” says Dr. Rashid. “It’s not lecturing at you. It’s saying, ‘Here’s this character’s experience. We’re inviting you to that experience and inviting you to think and reflect on your own experiences.’ And that’s the work of great art.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A cleansing turn in Honduras

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Between 1990 and 2020 the number of migrants from Central America increased 137%, according to United Nations figures. Refugees and asylum-seekers from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador accounted for 72% of the total. The outflow from Honduras rose 530%.

Yet for Western Hemisphere leaders gathering this week in Los Angeles to address the “root causes” of human displacement in the region, another number may be more important: 61%.

That’s the most recent measure of public support for Xiomara Castro. The first female president of Honduras, she has established a national anti-corruption council and repealed a public information law that enabled officials to invest millions of dollars in public funds without disclosure.

“The immediate effect of Xiomara’s election is to wake up with hope,” Nessa Median, a Honduran activist, told Women’s Media Center recently. “There are people who decided to suspend their plans to migrate because they know that the woman taking power will do it differently from what the last governments have been doing.”

Rooting out corruption in a country where 70% of the people live in poverty marks a step toward addressing the economic drivers of migration. It also starts a process of entrenching new norms of public good.

A cleansing turn in Honduras

Between 1990 and 2020 the number of migrants from Central America increased 137%, according to United Nations figures, from 6.8 million to 16.2 million. Refugees and asylum-seekers from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador accounted for 72% of the total. The outflow from Honduras rose 530%.

Yet for Western Hemisphere leaders gathering this week in Los Angeles to address the “root causes” of human displacement in the region, another number may be more important: 61%.

That’s the most recent measure of public support for Xiomara Castro. The first female president of Honduras, she entered office in January promising a raft of reforms to tackle corruption, strengthen democratic institutions, and safeguard the rights of women and minorities. A Mitofsky poll in April found public support increased 10 points in her first four months – reflecting a broader desire in Latin America for new leadership that is honest and inclusive.

“The immediate effect of Xiomara’s election is to wake up with hope,” Nessa Median, a Honduran activist, told Women’s Media Center recently. “There are people who decided to suspend their plans to migrate because they know that the woman taking power will do it differently from what the last governments have been doing.”

The Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles marks the ninth time since 1994 that leaders from across the Americas and Caribbean have met to build stronger political and economic ties. That goal has met numerous setbacks over the years from populist and autocratic regimes. President Joe Biden had hoped to chart a more united way forward with a focus on causes of migration: weakened democracy, climate change, economic hardship, and violence.

Ms. Castro is a key partner in that project. She is part of a small cadre of reform-minded officials in countries like Ecuador and Guatemala taking on systemic corruption. Her task is formidable. She inherited the presidential sash after 12 years of democratic erosion under the previous ruling party. So far she has established a national anti-corruption council and repealed a vaguely defined public information law that enabled officials to invest millions of dollars in public funds without disclosure.

Most dramatically, in April, she allowed for the arrest and extradition to the United States of her predecessor, Juan Orlando Hernández, on narco-trafficking and weapons charges.

Those steps underscore both the urgency and symbolism of reform. The Honduran Constitution bars presidential incumbents from serving consecutive terms. Ms. Castro has just four years. Rooting out corruption in a country where 70% of the people live in poverty marks a step toward addressing the economic drivers of migration. Perhaps more importantly, it starts a process of entrenching new norms of public good.

“The fact that Juan Orlando Hernández has fallen sends a great message ... that presidents do not always go unpunished,” Jennifer Ávila Reyes, editorial director and co-founder of activist group Contracorriente told PassBlue media outlet. “People feel more empowered now. ... But it will not be so easy to dismantle the entire structure that these actors have left behind, many of whom still have power in the territory, like mayors, governors, legislators.”

On the day the summit opened in Los Angeles, a new caravan of migrants from Central America and the Caribbean – estimated to be the largest in history – set off northward from Mexico’s southern border. Not by coincidence they are reminding regional leaders of the toll of poor governance. Yet in one point of origin, Honduras, a restoration of democracy is underway.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Always meaningfully employed

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kim Crooks Korinek

Recognizing that God cares for and values all of His children opens the way for opportunities to experience divine goodness more tangibly, as a woman found during a job search.

Always meaningfully employed

Newly single. New housemates. No job. Bills accruing. And a borrowed car. That’s how I started out on an urgently needed job search many years ago.

Having grown up in Christian Science, I was familiar with this idea from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science: “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (p. 494). I knew from experience that this was true about divine Love, God. But how was this going to work out in my current situation?

Christian Science, based on the Bible, also teaches that God has created all of us full of joy and gladness; we have an innate joy and desire to do good that come from God. Recognizing our true, spiritual identity as God’s offspring, or expression – and therefore our relation to one another as brothers and sisters – empowers us to do our part in helping meet the world’s need for truth, health, and happiness.

To find a job was certainly my desire. But I had more to learn, on a deeper level. Science and Health states, “Desire is prayer; and no loss can occur from trusting God with our desires, that they may be moulded and exalted before they take form in words and in deeds” (p. 1).

I was on my way to an interview when I saw a poster in the window of a Christian Science Reading Room that said, “You are already employed.” I ran in. “Please explain that poster!” I hurriedly asked the person working there, who smiled. We had a wonderful discussion that left me understanding more about God, and four main things came to me:

• Our completeness: God supplies everything we need. This includes being employed at every moment in utilizing all the spiritual qualities that God has given us in whatever we are doing each day. In this way we can each be going about our heavenly Father’s business, following Jesus’ example (see Luke 2:49).

• Our purpose: It is already set. God knows, places, and paces us. We can lean on God and let divine goodness be expressed in all we do. Goodness multiplies, so we can start right where we are. In “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” Mrs. Eddy encourages rising “above the oft-repeated inquiry, What am I? to the scientific response: I am able to impart truth, health, and happiness, and this is my rock of salvation and my reason for existing” (p. 165).

• Our future: God exists in the eternal now, and therefore expresses goodness, joy, and purpose in each of us, eternally. With gratitude, we can count on God’s guidance and protection – always.

• Our value: God, Love, created each of us in His image and likeness. All things created by God have value and purpose, and all of God’s ideas – including us – are harmonious. God’s ideas can’t compete with each other, judge each other, or withhold something of value from one another, because we are each a complete, full, and unique expression of Love’s goodness.

I went on to the interview with new confidence that I was already employed and valued, and that we all were united in the same purpose of seeing good. I felt I was going to the interview not in desperation, but with a goal of imparting goodness as best I could and witnessing divine Love in operation. I saw that there was reason for hope both for me and for the interviewer – their needs would be met in finding the right candidate, and even if that wasn’t me, I trusted in God to uplift and inspire in ways that would lead me forward.

It turned out that the interview went very well, I got the job, and I started work the next week!

Recognizing that God has given us all we need in order to know and reflect His goodness lifts the fear that we won’t have what we need. It “mould[s] and exalt[s]” our motives to a higher, nobler goal: to see how divine Love is already working its purpose out for everyone. We can be employed to be a blessing wherever we are. And that’s a job God has for all of us.

A message of love

Goodbye, golden arches

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about young Americans who are forging spiritual paths that don’t necessarily conform to religious traditions.