- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- One country, two histories: What does it mean to be an American?

- Diverse Israeli coalition made history. But has it been a success?

- Amid rain and rockets, Ukrainian farmers keep working the soil

- Power plants that burn wood: Clean energy or major polluters?

- Kick off summer with the 10 best books of June

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

This biographer’s mantra: ‘Every life is a gift’

April Austin

April Austin

As a people watcher, I try to imagine the lives of those whose paths cross mine. I devour biographies with a similar desire to know the details of someone’s life.

A biographer’s role is “helping readers bridge the gap between their experience and a life from the past,” says Megan Marshall, winner of this year's Biography International Organization Award.

Ms. Marshall has written three biographies of extraordinary women, including “Margaret Fuller: A New American Life,” which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2014.

In the case of Fuller, a 19th-century journalist, feminist, and colleague of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “she had a vision for herself that really didn’t exist [in society].”

When readers see themselves and their times reflected in a biography, it can give them perspective, Ms. Marshall says. “There is so much to be worried about and so much that seems hopeless. But if you … look at other times when there seemed to be no hope ... you’ll see how people rose up anyway,” she says. “That is one of the most important things a biographer can do.”

She continues, “Just seeing how people renewed their hope, what right do we have to give up when people in extremely dire situations used whatever tools were available to them to try to make a difference?”

Readers may wonder how one person can change the trajectory of a society. Ms. Marshall explains the concept of a “trim tab,” a favorite idea of inventor Buckminster Fuller, a grandnephew of Margaret Fuller. “A huge steamship or an airplane will have a trim tab, and just moving it the slightest bit can alter the direction,” she says. “I like to think that someone like Margaret Fuller or Buckminster Fuller could just make a little difference in the huge stream of life.

“We can take those messages of those who didn’t give up,” she says. “Alternatively, you can learn from people who didn’t make it. Everyone is worthy of remembrance and ... every life is a gift. And what you do with that gift is up to you.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

One country, two histories: What does it mean to be an American?

How do you create a sense of shared community when a country’s founding stories are no longer agreed on? Part 2 in a series.

How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

Most schoolchildren recite the Pledge of Allegiance and learn patriotic songs. But beyond pageantry, many educators are rethinking which topics and voices they should emphasize, trying to reconcile the country’s multicultural roots and its founding principles. The long-standing narrative of U.S. history textbooks, that the country’s overall arc tilts toward progress, is itself under challenge.

Two approaches to American history that have captured public – and critical – attention recently are best known by their dates. The 1619 Project puts more focus on the role of slavery and enslaved people, while the Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum takes a more traditional approach.

Visits to classrooms where each is being taught offer insights into the differences, but also show the similarities: extensive discussion, reading and analyzing texts, and expectations for students to contribute to society. Educators at the schools talk about the need to create informed citizens, ready to participate in the work of democracy.

“We’ve always fought about the history curriculum,” says Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian. “But I think in prior eras, the fight was really about who should be included in the story; it wasn’t about what should the story be. And that’s the fight now.”

One country, two histories: What does it mean to be an American?

How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

During the past two years, that question has flowed through cultural battles over what’s taught in classrooms – particularly relating to history and race.

It popped up when President Donald Trump called for more “patriotic education” and when some educators embraced using the 1619 Project in schools to reframe the traditional U.S. origin story. Also part of the mix: steps taken by dozens of states aimed at limiting instruction related to the concept of critical race theory.

Most schoolchildren already recite the Pledge of Allegiance and learn patriotic songs. But beyond traditional pageantry, many educators are rethinking which topics and voices they should emphasize, trying to reconcile the country’s multicultural roots and its founding principles. The long-standing narrative of U.S. history textbooks, that the country’s overall arc tilts toward progress, is itself under challenge.

“We’ve come to this inflection point in our disagreements about what America is and what it means,” says Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian at the University of Pennsylvania.

“We’ve always fought about the history curriculum, but I think in prior eras, the fight was really about who should be included in the story; it wasn’t about what should the story be. And that’s the fight now,” says Professor Zimmerman.

A majority of Americans are in favor of teaching “the full history of America – including the terrible things that have happened related to race and racism,” according to a September 2021 report based on a survey of registered U.S. voters. They are more divided on the extent to which racism is a current problem and whether schools should focus more on teaching about it. Beyond that, most also agree that school should teach young people to love their country.

But which version of it? Two approaches to American history that have captured public – and critical – attention recently are best known by their dates. The 1619 Project reframes U.S. history, focusing on slavery and its ongoing legacy. It appeared first in The New York Times, created by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, and went on to win a 2020 Pulitzer Prize for commentary. The 1776 Report, commissioned by Mr. Trump and released in January 2021, and the separate 1776 curriculum – produced by Hillsdale College in Michigan – champion a traditional view of America’s founding.

Visits this spring to classrooms where both approaches are being used offer insights into the differences in what’s highlighted in each – but also show the similarities: extensive discussion, reading and analyzing texts, and expectations for students to contribute to society. Educators at the schools talk about the need to create informed citizens, ready to participate in the work of democracy.

A focus on perspective

As of yet, there’s no national data on how many of the country’s roughly 99,000 K-12 public schools use the 1619 Project or the Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum. The Pulitzer Center in Washington produces K-12 lesson plans for the 1619 Project, available for public download. This school year, individuals from 40 education organizations participated in a 1619 Project network cohort, and a similar number of organizations are expected to participate next school year.

“This project asks students to really consider what is the history of the United States and whose perspective has been presented to you before,” says Fareed Mostoufi, associate director of education at the Pulitzer Center, a nonprofit that supports journalism focused on underreported issues. “We want students, these are our future leaders, making informed decisions and being curious.”

The goal of using the 1619 Project – included in the district’s Emancipation Curriculum – is to empower students of color to know their greatness, says Fatima Morrell, the associate superintendent for culturally and linguistically responsive initiatives at Buffalo Public Schools in New York. It’s also to train students to be informed and critical thinkers who are prepared to live in a democratic society.

“It’s an American ideal to fight for justice for all. Our country was founded on those ideas,” says Dr. Morrell, in a phone interview a month before the May 14 grocery store attack in her city, when a gunman killed 10 Black people. The Emancipation Curriculum, introduced in the 2020-2021 academic year, helps “prevent the Derek Chauvins and George Zimmermans” of the world, she says, referring to the former police officer who murdered George Floyd and the man who killed Florida teen Trayvon Martin.

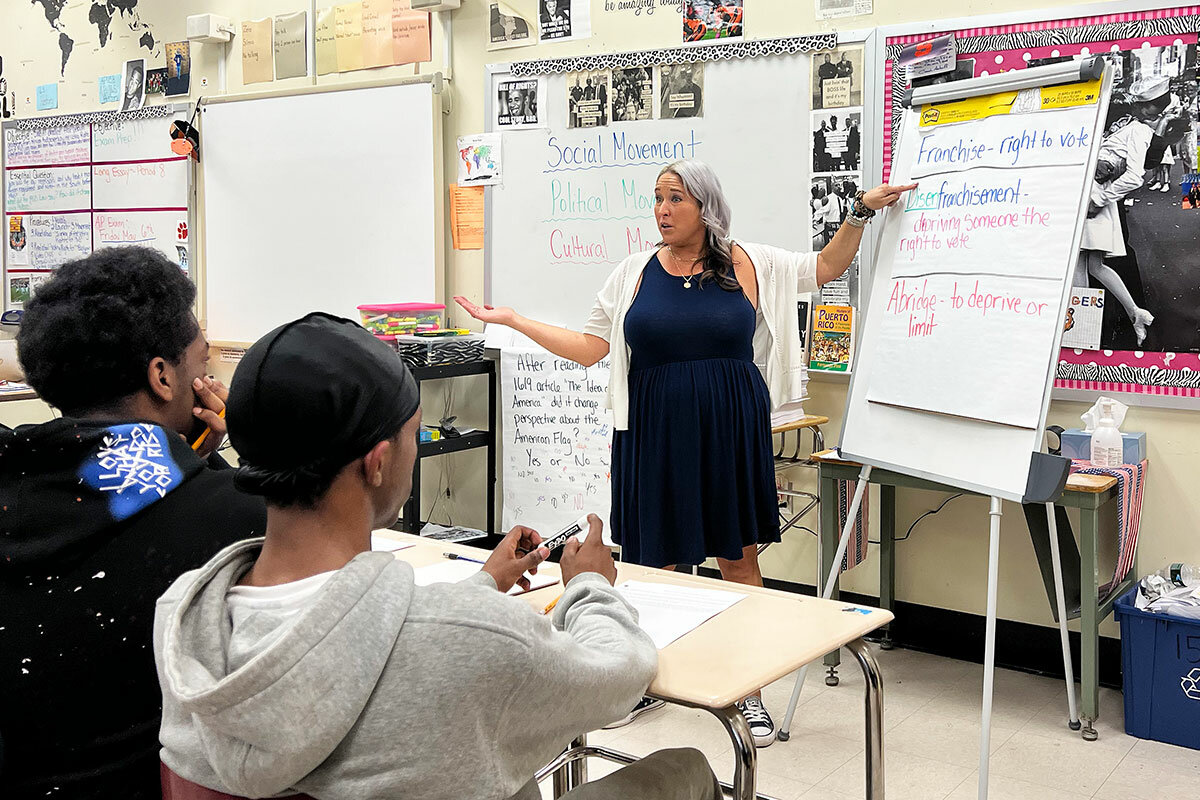

Use of the 1619 Project content in the district engages students in a variety of ways. During the school year, an 11th grade U.S. history class at Lewis J. Bennett School of Innovative Technology #363 read and discussed Ms. Hannah-Jones’ opening 1619 Project essay on democracy, in which she grapples with her view of the American flag.

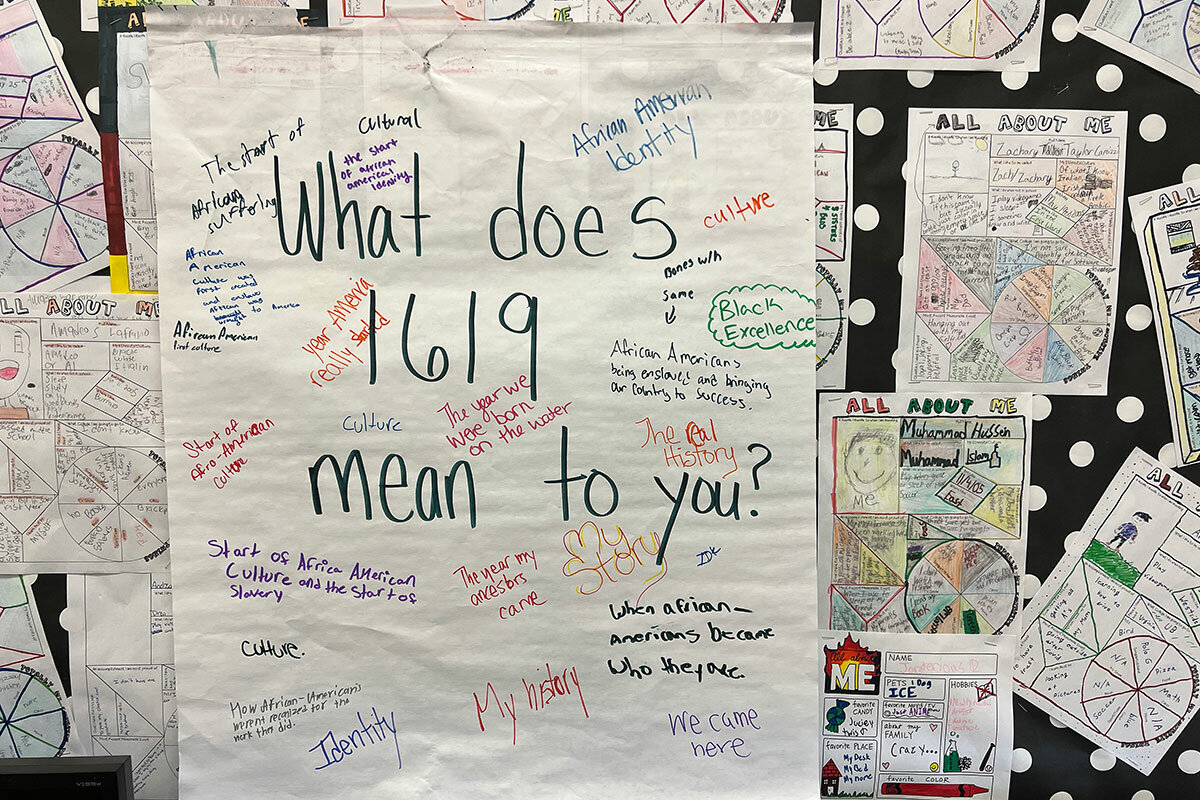

Large white flip-chart papers still hung on the wall in early May with prompts from the unit and student responses. One question reads, “What does 1619 mean to you?” Student comments include, “African Americans being enslaved and bringing our country to success” and “my history.”

Teacher Genah Lasby sees value in looking at all aspects of U.S. history. “In order to unify, we have to see the problems and issues that have occurred throughout time,” she says. “We all make mistakes, including the United States. And that’s OK, because we can learn from it, we can change, and we can make it better.”

Several miles away, Deborah Bertlesman starts her ninth grade English language arts class at Frederick Law Olmsted #156 by asking students to write about and discuss a quote from one of the essays in the project.

“Slavery gave America a fear of black people and a taste for violent punishment. Both still define our criminal-justice system,” the quote reads, part of lawyer Bryan Stevenson’s essay.

Students also write down information they see in the essay that confirms or challenges the story of American history they’ve already learned. During discussion, some students say they wonder whether the U.S. justice system is backsliding, after they read about some of Mr. Stevenson’s clients picking cotton at a Louisiana prison on the grounds of a former plantation.

Class discussion emphasizes actions students can take and their future impact on society – ideas reflected in posters on the walls with messages like “Tell your story” and “You are powerful.” The school building serves almost 900 students in grades five through 12, of which 68% are students of color. Median household income in the city is just under $40,000.

Chase Wood wants to become a civil rights lawyer. One of her research projects for the class this year was on how Black people interact with the criminal justice system. “I want to be that one peaceful person who goes to fight for people and civil rights,” says Chase.

Ms. Bertlesman ends by asking the class to respond to the prompt, “What is one thing you can do to continue to advocate for justice and change the world for the better?”

She views the 1619 Project as an opportunity to bring up perspectives that weren’t included in schools before, rather than an attack on American values, as some critics have charged. She considers systemic racism to be a truth that students and teachers should have “complex” discussions about, rather than ignore.

“Good citizens criticize. Good citizens question. That’s democratic – that’s democracy if I’ve ever heard of it,” says Ms. Bertlesman, who has not read the 1776 curriculum.

“It’s about giving them the evidence”

The Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum is also available for public download. Hillsdale College runs a network of K-12 classical education schools, which currently includes 57 member and affiliate schools with a mixture of public charter and private schools. The free 1776 resources, including primary documents and lesson plans, are culled from the history curriculum that Hillsdale has offered its schools for more than a decade.

“It’s not about pushing a particular agenda. It’s not about making sure students have access to a specific narrative,” says Kathleen O’Toole, assistant provost for K-12 Education at Hillsdale College. “It’s about giving them the evidence so they can go about learning what happened in American history, and then once they understand what’s happened, and have read the associated documents, then they can make a judgment for themselves about what it means and whether it’s good or bad.”

“We’re not afraid of asking hard questions,” she adds.

Oscar Ortiz is an immigrant from Honduras who is starting Heritage Classical Academy, a Hillsdale public charter school in Houston that expects to open in 2023. He says the history curriculum will help students understand how the ideas of America – like equality, liberty, popular sovereignty, and the rule of law – developed and why they are important.

Students “are going to learn what it means to be [American], what are the ideas or principles that set us apart from the world, and they will never feel that they have to give up their heritage or cultures as they do that,” says Mr. Ortiz.

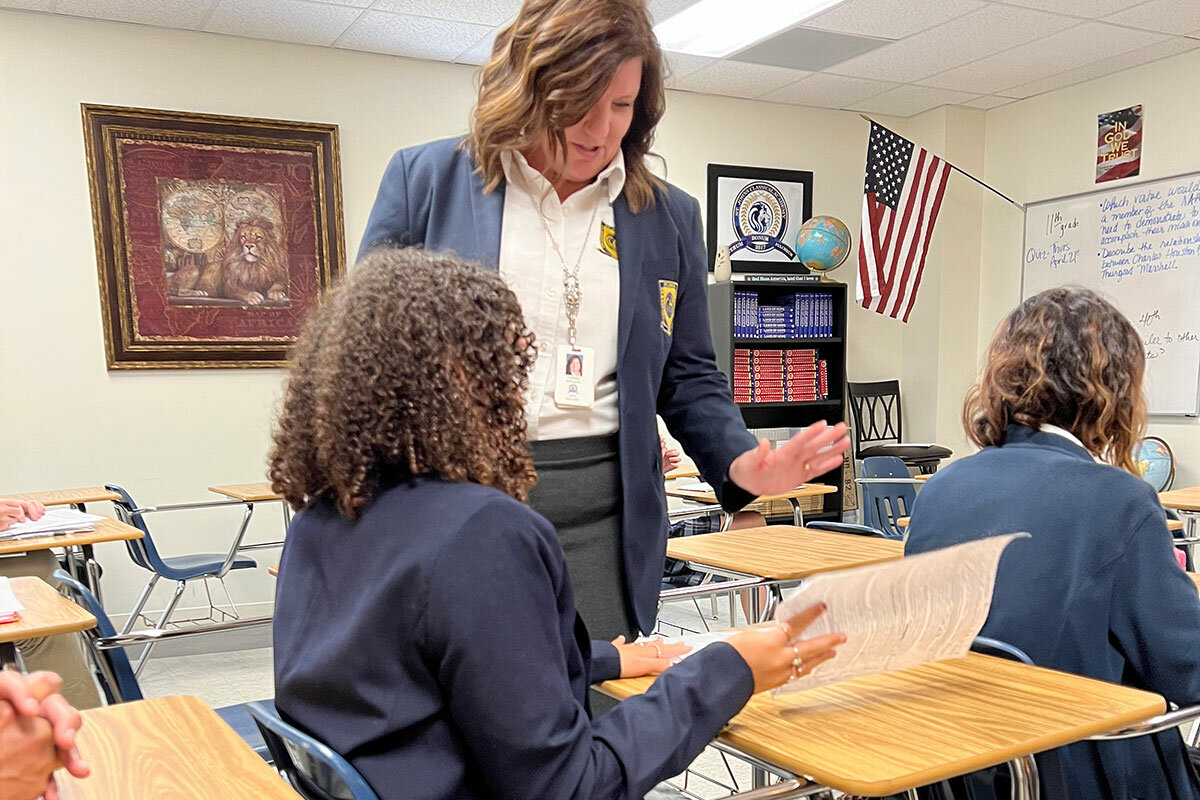

In Florida, students in Hillsdale schools spend half of each school year on American history, from kindergarten on. In April, 11th graders in a U.S. history class at St. Johns Classical Academy, a public charter school in Fleming Island, read aloud from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

Their teacher, Carmen Burgess, poses questions for discussion including, “How should we determine if a law is just? Which virtue is shown in Dr. King’s letter? Which virtues were denied to Dr. King and the other protesters?”

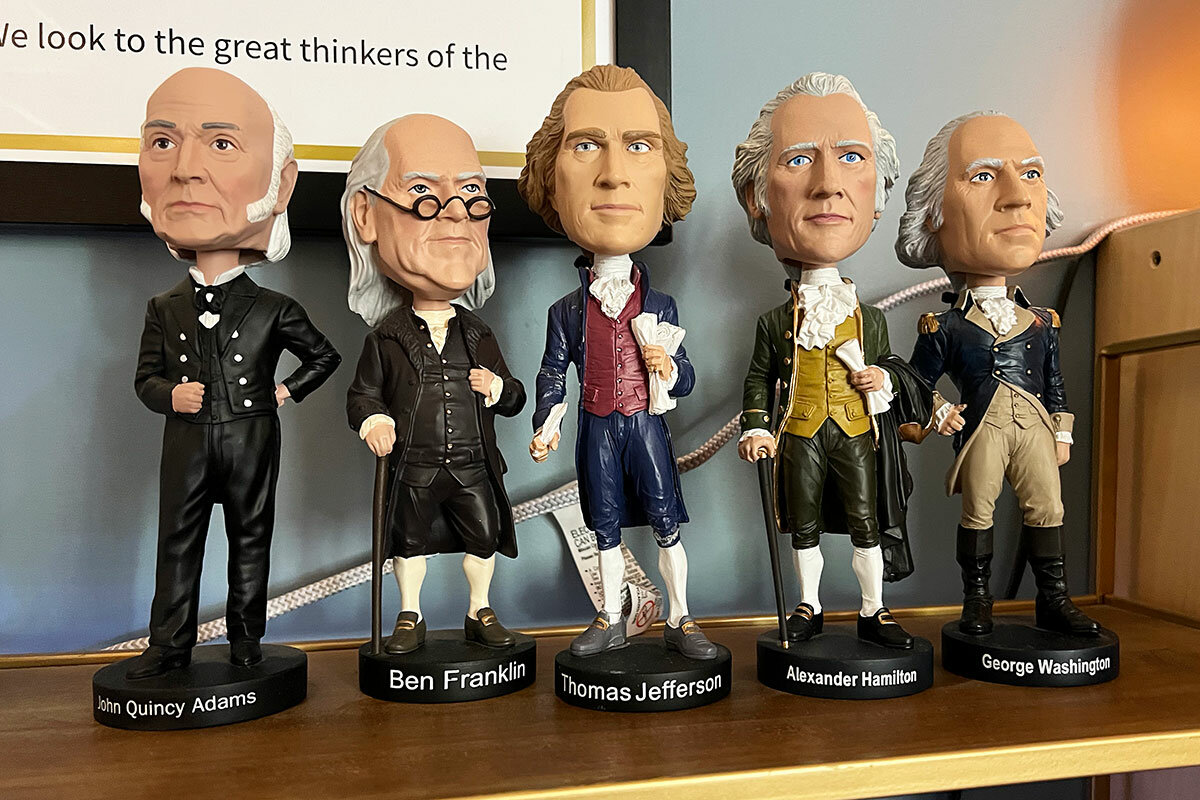

Ms. Burgess wears the same school uniform as her students, a navy blazer with an embroidered school seal. A poster of “In God We Trust” sits under the American flag in her classroom. The hallways are dotted with portraits of Founding Fathers and classic Western art.

The school, which opened in 2017 and awards seats by lottery, educates 800 K-12 students, with over 1,000 more on a waiting list, according to the school headmaster. The school is built on the property of a former church in a suburb of Jacksonville where the median household income is $101,000. The student body is 77% white.

The class talks about Dr. King’s intended audience and what he means when he writes of the feeling of “nobodyness” imposed on Black people by segregation and the different experiences of white and Black people in the 1960s.

“Does this kind of thing happen only in America?” asks Ms. Burgess at the end of class. Her students reply no, and they list other countries with contemporary strife, like Myanmar. She points to the poster of the school’s standards of virtues and encourages students to pick out and practice one.

One of the students, Grace Holton, says she plans to be an aerospace engineer. She expects to vote when she’s 18 and considers her school a place where she’s learning values that she’ll draw on as she eventually participates in U.S. civic life.

“We’re young. This is where you shape yourself for the rest of your life,” Grace says of her school. “At first when we came here, it was like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re pushing these virtues at us again, can’t they stop, we’re good people!’ But it kind of sticks and then you start noticing this person was really displaying integrity or that person really needs to work on their citizenship.”

Ms. Burgess has not read the 1619 Project and believes media coverage of history debates is divisive. “Anybody can use history to try and prove any point based on a perspective,” she says. “[Americans] really have more that unites us than divides us. We’re not perfect and we talk about that all the time. We clearly have failed from time to time and yet we also have created ways to repair the breaches.”

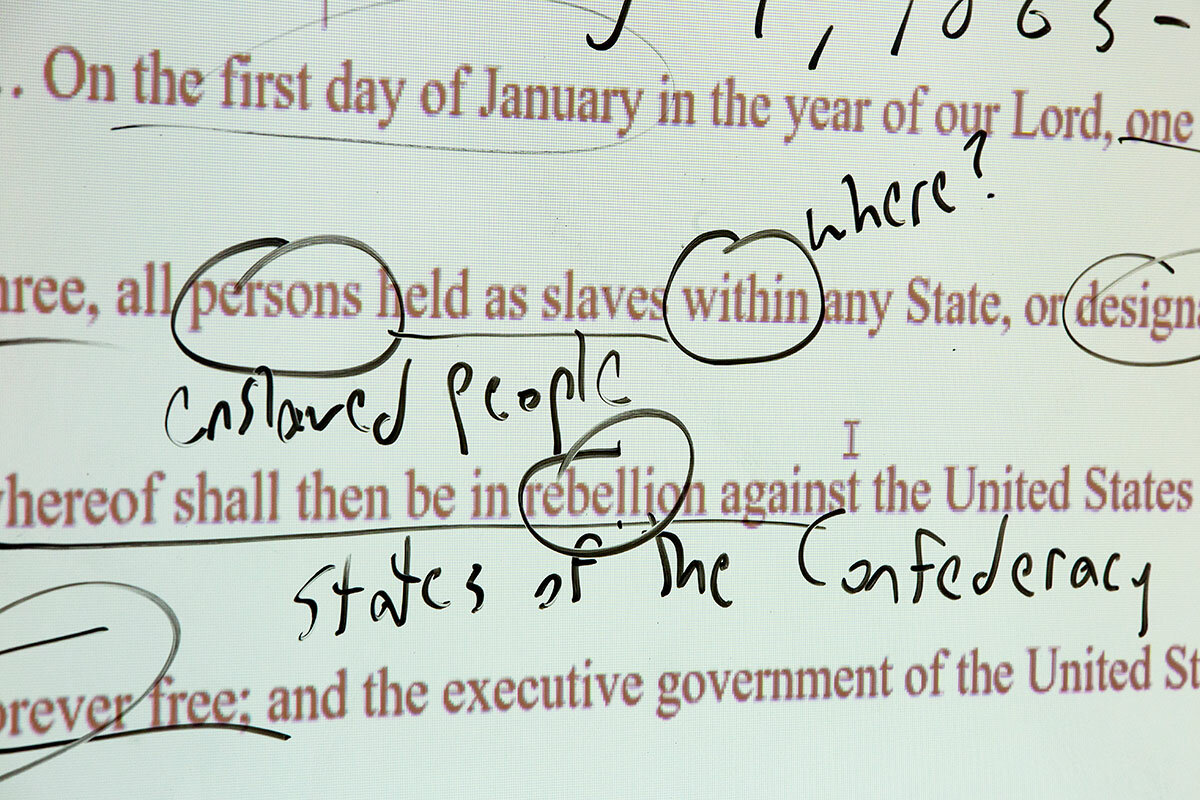

At another Hillsdale network school nearby, Jacksonville Classical Academy, school head David Withun works with seventh graders on a unit of Civil War history, including reading and annotating Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and filling out timelines of key dates.

“The way that I teach ... is as the story of the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. We distill those to things like liberty, equality, republican form of government, and self-government, and the rest of the story is a commentary upon those and a battle over the meaning of them,” says Dr. Withun. The school opened in downtown Jacksonville last academic year. It serves a diverse student body, with about 58% students of color.

Dr. Withun, who wrote a book on W.E.B. DuBois published by Oxford University Press in March, is concerned about a lack of familiarity with history that some of his students arrive with, like one student who thought King was a Civil War abolitionist.

With the school’s approach to teaching, he says, students are able to engage and respond with “‘Here’s why I think that Roger Taney is wrong in the Dred Scott decision ...’ and ‘Here’s why I think Frederick Douglass is right and here’s what Frederick Douglass means to my own life.’ Those sorts of interactions with these really challenging texts inspire the students and help them to think critically about what it means to be an American, what it means to be a citizen, and their place in the larger story of our country.”

“Contested American identity”

Does it matter to American democracy if there are different approaches to teaching students U.S. history?

In a senior education seminar class that he teaches, students read both the 1619 Project and the 1776 Report and analyze how differing interpretations of U.S. history are formed, says Charles Dorn, professor of education history at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine.

“The [public] debate over these two bodies of knowledge brings into sharp relief something that consistently has existed over time in the U.S., which is this contested American identity,” says Professor Dorn, co-author of the 2018 book “Patriotic Education in a Global Age.” “It also suggests ... a fundamental misunderstanding on the part of Americans on what history is,” he says.

All history is interpretation of facts, he says. The assignment he gives students is meant to highlight this.

With a nation as big as the U.S. and its long-standing fragmented education system, “to some degree it’s inevitable” that history won’t always be taught in the same way, says Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute based in Washington, D.C.

Mr. Petrilli says commonality can be found by focusing on the state standards for history and civics instruction. He points to an analysis the Fordham Institute conducted in 2021 of the history and civics standards in all 50 states, which found that the five states with the strongest standards in both areas were a mix of blue and red states.

“They do it in a way that’s patriotic but also critical by getting into the details,” he says, “so it’s doable and that’s what we should aim for.”

The potential for common ground is more robust than partisans on either side might believe.

“When you look at the 1619 materials and 1776, as an educator, parent, if you haven’t completely been sucked into toxic polarization, the heart and mind must go to ‘Isn’t there some room for both/and here?’” says Eric Liu, executive director of the Citizenship and American Identity Program at the Aspen Institute and CEO and co-founder of Citizen University in Seattle. “The fact is, there is more overlap and opportunity for synthesis than one might think between these two.”

This story is the second in a four-part series:

Part 2: How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

Part 4: How has parental participation in public schools shaped U.S. education?

Diverse Israeli coalition made history. But has it been a success?

The historically diverse Israeli government formed a year ago and now fraying was by definition a grand experiment in democratic cooperation. Is that enough to leave a positive legacy?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Neri Zilber Contributor

This week was supposed to be celebratory for the Israeli government led by Prime Minister Naftali Bennett as it marked a year in power. Its very existence, bringing together right and left and, for the first time, an Arab Israeli party, to cooperate and focus on consensus domestic issues, was one of the “greatest experiments in global politics,” as a senior government official puts it.

The coalition, however, is teetering. It has lost its parliamentary majority, and is on the verge of becoming a minority government that can be voted out of power.

Yet it has had success.

“The experiment over the past year has been whether a diverse coalition can work together, find compromises, and a common way forward ... as an antidote to increased polarization and populist nationalism,” says the government official. “In this sense it’s a resounding success.”

Mohammad Magadli, a prominent Arab Israeli television commentator, says even if the government were now to fall, there would be no going back.

“After this recent period of crisis ... you still have a majority of Arab Israelis in favor of further integration in national politics,” he says. “And for Israeli society ... its entire approach to the Arab Israeli community has changed. ... It’s a change in the whole social and political status of Israel’s Arab citizens.”

Diverse Israeli coalition made history. But has it been a success?

This week was supposed to be celebratory for the Israeli government led by Prime Minister Naftali Bennett as it marked its first anniversary June 13.

The eight-party coalition that had toppled the long-serving Benjamin Netanyahu was the most diverse and unlikely in the country’s history – one of the “greatest experiments in global politics,” as a senior government official puts it.

Its ranks included ultranationalist right-wingers, pro-peace leftists, centrists, and, for the first time ever, an Arab Israeli political faction, all coming together to govern.

These disparate parts agreed on very little, save for replacing Mr. Netanyahu and avoiding yet another election cycle after four largely inconclusive ballots between 2019 and 2021. The parties vowed to focus on consensus domestic items like the economy, housing, and transportation, and avoid more politically charged issues like the conflict with the Palestinians and West Bank settlements.

And to an extent, say analysts and some government officials, it has been a success.

“The experiment over the past year has been whether a diverse coalition can work together, find compromises, and a common way forward ... as an antidote to increased polarization and populist nationalism,” says the senior government official, who requested anonymity. “In this sense it’s a resounding success.”

Yet the coalition now finds itself teetering.

After the government failed to pass a crucial parliamentary bill last week, Nir Orbach, from Mr. Bennett’s pro-settler Yamina party, appeared to snap.

“You don’t want to be partners; the experiment with you has failed,” he screamed in the Knesset at a coalition member from the Arab Israeli Ra’am faction who had voted against the bill. On Monday Mr. Orbach said he was leaving the government, but was giving it a week to pass the measure before he would vote to topple it.

The coalition’s slim one-seat majority in parliament had already been wiped out after another key lawmaker from Mr. Bennett’s party defected to the opposition in April. Recent weeks have seen other coalition backbenchers threaten to defect or openly vote against the government.

Most analysts now believe snap elections are just a matter of time, and could possibly be called in the coming weeks.

Lasting change

But even if the government falls, does that mean the grand experiment failed? Some argue it may have forever changed Israel’s politics.

The latest crisis was due to emergency legislation that for decades had been routinely passed every five years, extending Israeli civil law to settlers living in the occupied West Bank. Two Arab Israeli coalition lawmakers, from Ra’am and the leftist party Meretz, voted against the bill, scuttling passage and drawing the ire of Mr. Orbach and other ultranationalists (no matter that a parliamentary majority was uncertain even if the two had voted in favor).

“There is no way not to come to the conclusion that a stable coalition can only happen when it relies on Zionists who served in the army,” Communications Minister Yoaz Hendel, of the right-wing New Hope faction, told party activists over the weekend. “There is a wider meaning to this than just the possible toppling of a government.”

But among Arab Israeli analysts and voters, as indicated by recent polls, there is a sense that increased political participation, and cooperation with Jewish factions, are becoming the new normal. That there is no going back.

Government leaders have attempted to project business as usual amid the turmoil, vowing to fight on and highlighting the many accomplishments of the “government of national salvation,” as they’ve come to describe it.

“We are not giving up on our country. We are not giving up on the possibility of cooperation between people who have different views, who love this country to the same degree,” Mr. Bennett told his Cabinet Sunday.

Attacks by Netanyahu

The formation of the current government was highly acrimonious from the start. Mr. Bennett’s decision to break from Mr. Netanyahu and partner with leftist and Arab parties was slammed by his base as a deep betrayal.

Mr. Netanyahu and his supporters have for the past year consistently tarred the prime minister as a “cheat” and a “liar,” calling the government illegitimate. Opposition rallies have demanded that a “Jewish government” be returned to power and that cooperation with “terrorist supporters” – that is, the Islamist Ra’am party – be halted immediately.

This Netanyahu-led “poison machine,” as Mr. Bennett calls it, has ensured that Israel remains a deeply divided and polarized country. Mr. Netanyahu is still the most popular politician nationally, and his Likud party, too, leads in all polls.

The fear expressed by government officials is that in any snap election, the Likud and its traditional far-right and ultra-Orthodox political allies may succeed in winning an outright parliamentary majority.

Mr. Bennett has therefore framed the choice now facing the country as similar to last year’s: “to move forward with a functioning state, or to descend again into chaos, internal hatred, external weakness, and the enslavement of the state to the needs of one man,” as he wrote in a recent pamphlet to the public, alluding to Mr. Netanyahu’s ongoing corruption trial and extralegal efforts to quash the charges.

Analysts credit the government with returning a modicum of normalcy to the political system, including passing a state budget after several years of instability, expanding diplomatic ties with neighboring Arab states, and soberly managing the country’s security challenges.

“The executive branch has actually been working really well – the various ministers are coordinated with each other, they give credit to each other, and they’re eager to prove to the public that they can make a difference,” says Tal Schneider, chief political correspondent for The Times of Israel.

Yet the government’s mere existence appears to be its biggest triumph.

“Even if this government falls, it was a historic year and a huge achievement, perhaps even a miracle,” Ms. Schneider adds. “In particular, breaking this taboo of bringing an Arab party into a ruling coalition. It’s bigger than anything else that has happened here over the past year.”

For Arab citizens, a historic shift

Arab citizens of Israel, 20% of the population, had never before been represented in government by an independent political faction, due to opposition from both their own politicians and the broader Jewish Israeli public.

Ra’am’s leader, Mansour Abbas, changed all that by first openly negotiating with Mr. Netanyahu and then striking a deal with Mr. Bennett and Foreign Minister (and alternate prime minister) Yair Lapid to join their coalition.

Mr. Abbas has over the past year condemned Palestinian attacks on Israelis and publicly recognized Israel as a Jewish state. In turn, the militant Hamas group has called him a traitor to the Palestinian cause, as have his opponents from competing Arab Israeli factions.

“Parallel steps [by both Arab and Jewish societies], this is the philosophy of our approach,” Mr. Abbas explained last week in an address to Reichman University in central Israel. “We’re not waiting for the change in order to say afterwards that we’re creating Arab-Jewish partnership. ... We’ve created the partnership despite all the differences and all the history and [competing] narratives. ... Through this partnership we’re creating the change.”

The Arab Israeli public appears to be highly supportive of this approach, with one recent survey showing nearly 70% approving of Arab political representatives joining a governing coalition.

Mr. Abbas has been adamant that this “experiment” in Arab-Jewish partnership has been a success, despite the naysayers within the coalition.

Arab Israeli officials and analysts, for their part, dispute the characterization of the political crisis as originating with Ra’am or other left-wing parliamentarians.

“Factually, over the past year, you can see votes by them in favor of what are termed ‘nationalistic’ or ‘security’ bills that clearly went against their morals and ideology,” says Mohammad Magadli, a prominent commentator for Israel’s Channel 12 News.

“Can’t turn back the wheel”

But even if the government were now to fall, he adds, there will be no going back – by either side.

“After this recent period of crisis, with all the political turmoil, terror attacks, and unrest at [Jerusalem’s] Al-Aqsa Mosque, you still have a majority of Arab Israelis in favor of further integration in national politics,” Mr. Magadli says.

“And for Israeli society – if not the world – its entire approach to the Arab Israeli community has changed. The moment you get to know something, you can’t turn back the wheel. It’s a change in the whole social and political status of Israel’s Arab citizens.”

The vitriolic opposition to any such change from many quarters of Jewish Israeli society is unsurprising, adds the senior government official.

“Any change of this magnitude takes time and brings about resistance,” the official says. “If we left politics tomorrow, it would still be the most important thing we’ve done. But we’re not leaving politics tomorrow.”

Amid rain and rockets, Ukrainian farmers keep working the soil

As war rages around them – sometimes even in their fields – Ukraine’s farmers are persevering to harvest their much-needed grains and export them to the rest of the world.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

War in Ukraine – a major breadbasket thanks to its highly fertile black soil – has the global food system reeling. Russia and Ukraine supplied nearly a third of the world’s wheat and barley before the outbreak of full-scale war. But last year’s corn and other grain harvests did not reach the international market because of Russia’s invasion.

In front-line regions, farmers work the fields knowing the risk of shelling and rockets rivals the odds of spring showers. In territories seized by Russia, they have adapted to occupation. Shortages of fuel, fertilizer, and storage space pose a challenge across regions. The motivation for farmers to carry on in such adverse circumstances ranges from the pragmatic to the patriotic.

“What will people eat if we don’t work here?” asks Valentyn Maksymenko, a farmhand on Dergoff farm in Tetiiv, Ukraine. “Everyone depends on us. The army. All Ukrainians. Everyone.”

With millions of people at risk of famine due to the war, Ukrainian farmers are finding themselves on the front lines of a global emergency.

“We don’t know what tomorrow will bring, but we will plant our seeds,” says Dergoff farm’s agricultural manager Oleksandr Chornyi. “Farming is key for food security and economic security.”

Amid rain and rockets, Ukrainian farmers keep working the soil

The Russian invasion of Ukraine feels far away from the Dergoff farm in the farming town of Tetiiv, as tractors spray fertilizer across freshly planted corn fields on a May sunny day.

Reminders come in the form of sturdy checkpoints in the town’s entrance – where “infiltrators” have been caught trying to smuggle weapons and night goggles – and a warplane cutting across the clear blue sky. Veteran farmhands see their presence in their fields as a matter of necessity and fret about the future.

“What will people eat if we don’t work here?” asks Valentyn Maksymenko, who has been farming for 25 years. “Everyone depends on us. The army. All Ukrainians. Everyone.”

Yet just a couple of miles away in one of the farm’s cavernous warehouses, unsold maize forms golden dunes. War in Ukraine – a major breadbasket thanks to its highly fertile black soil – has the global food system reeling. Russia and Ukraine supplied nearly a third of the world’s wheat and barley before the outbreak of full-scale war. But last year’s corn and other grain harvests did not reach the international market because of Russia’s invasion. Moscow’s warships block the maritime routes linking the southern strategic port of Odesa to the world.

In front-line regions, farmers work the fields knowing the risk of shelling and rockets rivals the odds of spring showers. In territories seized by Russia, they have adapted to occupation. Shortages of fuel, fertilizer, and storage space pose a challenge across regions. The motivation for farmers to carry on in such adverse circumstances ranges from the pragmatic to the patriotic.

“We are not on the front line now, but the day could come that we are on the front line or needed in the front line,” says Mr. Maksymenko’s colleague, Anatoliy Stelmakh. “We have children and grandchildren, so of course we are worried.”

With millions of people at risk of famine due to the war, Ukrainian farmers are finding themselves on the front lines of a global emergency, even if the conflict may not be threatening them immediately.

“We don’t know what tomorrow will bring, but we will plant our seeds,” says Dergoff farm’s agricultural manager Oleksandr Chornyi. “Farming is key for food security and economic security.”

Harvest, interrupted

Agriculture is a mainstay of the Ukrainian economy, with about a third of the population active in this sector. In recognition of the strategic importance of farmers, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy temporarily exempted them from military conscription. Out of the roughly 600 people who work in the vast Dergoff farm, 10 have gone off to fight.

“Many of our employees are willing to fight, but the conscription office has them on hold because they need experienced fighters,” says Bohdan Balagura, who is the mayor of Tetiiv but is well versed in the farm’s business operations, which he oversaw until 2020. “They are more useful here.”

The Dergoff farm is relatively well positioned to weather the economic storm thanks to diversification. Still, they expect a revenue loss of no less than 50% relative to last year.

“We are ready to go through hard times because we are certain that victory will come,” says Mr. Balagura, pointing to a giant nest on the chimney of the farm’s office, considered a good luck omen because it was built by a stork, the national bird of Ukraine. “Our family can easily leave the country, but we decided to stay here because we believe in victory.”

Ukraine grows enough grains to meet domestic consumption and export three-quarters of its output. But blocked ports mean producers can’t sell their grain. Rail alternatives via Europe have not been viable at the scale needed. Moscow has said it will lift the blockade only if Western sanctions are lifted.

“Ukraine, which can feed half the world, is isolated,” laments Mykola Gorbachov, president of the Ukrainian Grain Association, which unites grain producers, processors, and sellers.

The export of agricultural products is crucial to Ukraine. “More than 50% of foreign exchange earnings in Ukraine come from the export of agricultural products,” says Mr. Gorbachov. “Depending on the prices, this amount may be between $22 billion and $28 billion per year. From this you can conclude how important it is for our GDP. Wheat and corn and sunflowers are produced in all regions of the country.”

In the autumn, Ukraine made plans to export about 70 million tons of grains and oil seeds in the first half of 2022. It only managed to export 43 million tons as of Feb. 24, when Russia invaded the country, he notes. About 27 million tons of wheat and corn earmarked for exports are stuck. Of the 33 million tons of grain planted this year, 26 million were for export.

War has meant a 40% drop in production. “If last year we produced about 107 million tons of grain and oil seeds, this year we are expected to harvest about 65 million tons,” says Mr. Gorbachov.

“It is a danger to be here”

Most of the fields on Ihor Tkachov’s farm are devoted to winter wheat, a variety planted in autumn and harvested in summer. It is well suited to the cooler climate of northeast Ukraine. “We need to do something to save this harvest,” he says. “It is important to transfer grains out of the front-line zones because these are at the most vulnerable zones.”

Intermittent shudders shake the fertile soil underfoot as he speaks. That is the impact of incoming shells. Guttural pops mark outgoing fire and those have increased in intensity as Ukrainian troops have pushed Russian forces away from Kharkiv. Mr. Tkachov’s farm sits near the border with Russia, in the village of Skovorodynivka.

Russian troops have not marched on his property, but countless rockets have landed in his fields. Ukrainian forces spread mines in the area to stop Russian advances. Both have claimed farmers’ lives. He refuses to show his grain silos for fear that they be targeted by Russia, as has been the case elsewhere in Ukraine.

“It is a danger to be here,” says Mr. Tkachov, sporting a black vest against the morning chill. “I’ve never seen a planting season like this one. The traders were supposed to come on Feb. 24 or 25. Instead there were Russian planes coming. Rockets flying over the village.”

Two brave agronomists who work with him, Sasha Serdytyi and Slava Khrolenko, risked their lives twice venturing to nearby Kharkiv. They procured seeds and fertilizers as street battles raged and tank shells rained. “Suppliers understand that we need chemicals, seeds, and fertilizers,” says Mr. Tkachov. “Even if they had evacuated from Kharkiv, they came back to open up the storage facilities.”

“Everything needs to be done at the right time in farming,” says Mr. Serdytyi. “All we think about is whether we will wake up the next morning. All we want is to collect this harvest.”

“We work so that our children do not go through a Holodomor,” adds Mr. Khrolenko, referencing the 1932-33 state-generated famine in the Soviet Ukraine that killed millions of Ukrainian people. All three farmers grew up with stories about the horrors of hunger. Mr. Tkachov credits his grandmother for teaching him the value of bread.

Failure to work could spell hunger for their fellow Ukrainians and the world. “This is not just about Ukraine,” says Mr. Serdytyi. “Many countries depend on our exports.”

Dealing with the Russians

About 20% of Ukrainian land is now under Russian occupation, blocking 6 million to 10 million tons of grain. Dmytro, who declined to give his last name for security reasons, works for four agricultural companies employing 80 workers in the occupied region of Kherson in southern Ukraine. The agronomist, who once served in the Soviet Army’s rocket forces, decided to stay put along with his mother and his wife after Russia took over Kherson in early March. His sons left.

“Russians went through the Kherson region as if they were marching on a parade. So easy,” he says in a phone interview. “It doesn’t matter if you want it or not – sometimes we must communicate with them. They are so polite, it’s almost disgusting.”

Farming has carried on largely as normal under Russian occupation, he says. They have planted wheat, barley, rapeseed, and sunflowers on schedule. The region has been spared the relentless bombing endured in other parts of Ukraine, so there has been no war-related damage to agricultural facilities and fields. The inputs needed for the spring – fuels, seeds, chemicals, pesticides – were secured after the autumn harvest.

“We have everything, and we have ... nothing,” says the farmer, who is particularly upset by acts of petty theft and the difficulties he has procuring medicine. “Russians came and took one car from each farm. And now they’re driving around in our cars.”

Russia’s occupation of Kherson has also meant the rise of “dodgy dealers” who drive around buying grain for 4,000 hryvnia ($135) per ton, about 50% less than the regular price, he says. Some travel in cars with Crimean license plates and then transport the grain to the Black Sea port of Sevastopol, the second largest city in Crimea, which Russia annexed from Ukraine in March 2014. Ukrainian authorities estimate that about half a million tons of grain have been taken to Crimea by land and exported as Russian grain.

Despite the circumstances, the farmer is optimistic. The region, he says, expects a higher-than-average harvest. And he is among those who have not lost hope that the Ukrainian army can liberate Kherson by the end of the summer.

“We expect to harvest wheat, rapeseed, and barley while still under the occupation, and sunflowers when back in Ukraine,” he says.

Oleksander Naselenko contributed reporting to this story.

Power plants that burn wood: Clean energy or major polluters?

Is it honest and accurate to count power plants fueled by wood as clean energy? It’s a burning issue, literally, in the European Union and beyond.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The phrase renewable energy may evoke images of solar or wind power, but in the European Union, fully 60% of energy classified as renewable is generated by burning organic matter – most of it wood from forests.

The EU is in negotiations over what exactly should count as sustainable biofuel – with the added complication, now, of the war in Ukraine and efforts to pivot away from Russian fossil fuels as quickly as possible.

Proponents of bioenergy argue that burning wood can be a carbon-neutral process because the carbon released into the atmosphere will be reabsorbed by new trees growing where old ones were logged. Critics, however, say it will take decades for that to occur – time that, given the challenge of climate change, we simply don’t have.

“If you had asked me even two years ago if burning trees was better than burning coal I would have said, ‘Of course,’” says Martin Pigeon at Fern, a forest advocacy group. “But now we are living in a situation where the climate crisis is becoming very visible for all to see; we’ve already entered an emergency phase.”

Power plants that burn wood: Clean energy or major polluters?

In the north of England, surrounded by villages and farmland, lies a vast complex of concrete cooling towers that dominate the landscape.

These gray and somber structures might give the impression of traditional power generation, feeding on a feast of fossil fuels, but no longer. Instead of consuming copious amounts of coal, most of the boilers at the Drax power station now rely on a different menu: wood pellets, sourced from North American forests and shipped to the United Kingdom to keep the fires burning 24 hours a day.

This is bioenergy, and it’s classed as a clean source of energy by both the U.K. and the European Union, among others – playing a crucial role in their targets of renewable energy generation. Supporters see bioenergy as a critical asset in the transition to a cleaner future, even part of the longer-term mix, but critics are aghast that the felling of forests could ever be considered sustainable.

In tacit acknowledgment of this apparent paradox, the EU is currently in the midst of negotiations to classify what exactly can be counted as sustainable biofuel – with the added complication, now, of the war in Ukraine and efforts to pivot away from Russian fossil fuels as quickly as possible.

“Bioenergy – if it’s done sustainably – can really contribute,” says Andrew Welfle, a research fellow at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at The University of Manchester. “We have carried out much research working with industry, government, and academic partners scrutinizing its sustainability. In the vast majority of scenarios, bioenergy can provide energy with emissions far below those of coal or natural gas.”

Drax would certainly agree. And the power station in North Yorkshire accounts for 12% of the country’s renewable energy.

Others, however, are less convinced. A group of conservation organizations filed a complaint to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development last October, challenging many of Drax’s claims on sustainability. Just a few days earlier, Drax and 14 other firms were kicked off a global investment index of clean energy companies, as criteria for inclusion were tightened up.

Over in the European Union, where some of the other booted-out companies are based, the subject is no less controversial. Various EU bodies are hammering out their positions on revising what can be classed as “green” biomass, qualifying for subsidies. In a place where fully 60% of renewable energy is generated by the burning of organic matter, this is no trivial issue. And while biomass can refer to sources other than trees – crops grown to provide biofuel, for example – forest biomass is the most controversial, and it accounts for 70% of the EU’s bioenergy.

“Biomass, in all its different forms, is an integral part of our energy needs,” says Irene di Padua, policy director at Bioenergy Europe, a trade association that describes itself as the voice of European bioenergy. “When it comes to sustainability, we already have to respect quite strict requirements – how it’s harvested, where it comes from, what is the carbon footprint.”

But herein lies one of the key points of contention: Proponents of bioenergy argue that burning wood can be a carbon-neutral process because the carbon released into the atmosphere will be reabsorbed by new trees growing where the old ones were logged.

They also point out that the carbon released has been sequestered only as long as a tree has been growing, whereas the burning of fossil fuels is pumping carbon into the atmosphere that’s been locked away for millions of years.

The problem, however, is that it will take decades of growth before the new trees will have reabsorbed the same amount of carbon released by the combustion of their predecessors – time, say climate activists, that we simply don’t have. Moreover, because of the nature of wood, you have to burn more of it than you would of coal to produce a given amount of energy, thus releasing a greater quantity of carbon into the atmosphere in the interim.

“At the moment, it’s the worst of both worlds, because you’re using an energy source that adds the most carbon to the atmosphere, at the same time as cutting into your carbon sink,” says Martin Pigeon, forest and climate campaigner, and the focus person for bioenergy, at Fern, a forest advocacy group based in the EU.

“If you had asked me even two years ago if burning trees was better than burning coal I would have said, ‘Of course,’” continues Mr. Pigeon. “But now we are living in a situation where the climate crisis is becoming very visible for all to see; we’ve already entered an emergency phase.”

For now, the debate is less about whether to use bioenergy and more on how to make it as sustainable as possible. One particular concern: what parts of the trees are being used to fuel the bioenergy boom. The industry insists that it uses only waste products from other activities, tree parts that can find no other use and would otherwise be sent to landfill or left on the forest floor.

Various investigations, however, have questioned these assertions. A CBS report in April 2022 captured footage of mountains of logs at a pellet-producing plant in the United States. Photographic evidence showing a similar story was compiled from sites all over the EU by the Forest Defenders Alliance in the same month. In both cases, they query whether such quantities of hefty tree parts could not have found uses other than burning.

The concern is that rising bioenergy demand may be leading to logging that would not otherwise occur. In a letter sent to world leaders last year, hundreds of scientists, describing this very scenario, put their name to a plea not to “undermine both climate goals and the world’s biodiversity by shifting from burning fossil fuels to burning trees to generate energy.”

To alleviate some of these potential pressures, one EU proposal is to exclude from its definition of green biomass any wood that comes from “primary forests” – areas little disturbed by human activity to date.

“The effects of using biomass for energy have impacts on the natural environment and other environmental objectives, which deserve society’s attention, in addition to just climate,” says Ben Allen, executive director at the Institute for European Environmental Policy, in an email exchange.

The bioenergy industry, however, is lobbying to water down these proposals. In addition, at the end of January, 10 EU nations signed a letter to the European Commission, arguing that it was “too early” to strengthen the sustainability criteria for bioenergy. While it is not yet officially in the public domain, a spokesperson for the Commission confirms receipt of the letter.

The EU is expected to reach a conclusion on the matter no later than September, when a final vote is expected to take place. Amid the debate, many experts are wary of dismissing bioenergy out of hand.

One paper, for example, co-written by more than 20 scientists from institutions around the globe, argues that “narrow perspectives obscure the significant role that bioenergy can play by displacing fossil fuels now, and supporting energy system transition.”

“If you look at bioenergy over the years, it’s a dynamic picture,” says Dr. Welfle, whose work focuses on bioenergy, sustainability, and climate change. “In the U.K., it’s used in a big way for power generation, but power is likely to be decarbonized in a big way.”

He predicts that “in the future it’ll be much more targeted to niche sectors such as providing low carbon fuel options for aviation and shipping.”

Books

Kick off summer with the 10 best books of June

Our 10 picks for June include books about a Black horse trainer’s dignity in the face of racism, a train car full of commuters who learn to lean on each other, and a timely reimagining of America’s neglected shopping malls.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Monitor reviewers

“No entertainment is so cheap as reading, nor any pleasure so lasting,” wrote Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, an essayist and poet who lived in England in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

More than diversions, the books our reviewers selected this month offer both enjoyment and substance.

From novels that introduce quirky characters and invite a good laugh to weightier nonfiction about overcoming bias – including a memoir by a female NASA scientist – these titles will substantially enrich your reading.

Kick off summer with the 10 best books of June

Discover your next favorite book, whether you’re in the mood for insightful short stories about the immigrant experience, a startling fantasy novel about survival, or a deep exploration of a little-known aspect of Native American history.

1. Horse by Geraldine Brooks

“Horse” is not just about a racehorse but about race. This heart-pounding novel about a famous antebellum champion thoroughbred named Lexington and his talented, enslaved trainer circles two tracks, one historical, one contemporary, to highlight the ongoing scourge of racism in America.

2. A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times by Meron Hadero

Displacement haunts Meron Hadero’s superb debut short story collection. Hadero gorgeously illuminates quotidian moments to create unforgettable characters: a refugee learning English, a preteen confronting racism, and two friends whose lives can be tracked through the pages of “The Good Housekeeping Illustrated Cookbook.”

3. Last Summer on State Street by Toya Wolfe

Fe Fe Stevens’ Chicago neighborhood is under attack. As the housing authority tears down the high-rises the sixth grader and her friends call home, other threats edge closer – gang violence, drugs, hostile police. “Know what you want to do, so no one else ends up deciding,” urges a neighbor. Resilient and open-hearted, Fe Fe finds her way in Toya Wolfe’s moving debut.

4. Iona Iverson’s Rules for Commuting by Clare Pooley

“Never talk to strangers on the train.” It’s one of Iona Iverson’s “rules for commuting” – advice she promptly ignores in Clare Pooley’s buoyant novel. Flamboyant former “It Girl” Iona, overlooked and belittled at her London-based magazine job, gets drawn into an incident on the 8:05 to Waterloo. As the commuters begin to interact, community forms and stereotypes slide away.

5. The Wall by Marlen Haushofer

First published in 1962, “The Wall” offers a gripping survival story well tuned to today. A 40-something woman visiting a hunting lodge in the forest discovers she’s cut off from the world by an invisible, impenetrable wall. As she scrambles to secure food and fuel, her only companions – a dog, a cow, and a cat – teach and sustain her in this remarkable tale of perseverance.

6. The Candid Life of Meena Dave by Namrata Patel

When Meena, a photographer, inherits an apartment in Boston, her solitary life is upended. Cryptic notes, friendly Indian “aunties,” and a handsome neighbor all inspire her to search for answers to secrets from her past. This charming story wraps history and culture in a message of lives renewed.

7. The Angel of Rome by Jess Walter

Reading Jess Walter’s second collection of short stories, one is shepherded through sometimes gritty terrain, but with the constant assurance of finding light and unexpected laughs. He mines gold from the profound perspectives of his unique characters.

8. A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman by Lindy Elkins-Tanton

Lindy Elkins-Tanton, a planetary scientist, tells how she overcame obstacles to lead the NASA mission that will send a rocket to explore the massive asteroid Psyche. Her beautiful and inspiring memoir illuminates the challenges faced by women in science.

9. Meet Me by the Fountain by Alexandra Lange

Architecture critic Alexandra Lange’s fascinating cultural history explores the shopping mall, beginning with its birth in postwar America. She captures the mall’s role in providing freedom to some while excluding others, and offers ideas for how to re-imagine the empty shopping centers that now dot the suburban landscape.

10. We Refuse To Forget by Caleb Gayle

Caleb Gayle’s eye-opening account centers on Black members of the Creek tribe, who were long considered fully Creek but whose tribal membership was revoked in 1979. In tracing their history up to current legal efforts by descendants to be reinstated in the tribe, Gayle complicates our easy assumptions about American identity.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A South African answer to xenophobia

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In recent decades, a rapid rise in migrants displaced by war has tested many host countries. One country that has struggled with an influx of migrants is South Africa. As Africa’s strongest economy, it has drawn people from across the continent seeking safe harbor and opportunity. This has led to periodic bursts of violence against migrants. That’s not the case in Giyani, a town near the northern border with Zimbabwe, which is setting an example.

There the local citizens and migrant Zimbabweans have forged a seamless community built on social networks that transcend ethnic or national identity. “Peaceful and mutually beneficial relationships between South Africans and migrants can and do regularly exist,” wrote Shannon Morreira, a professor of anthropology at the University of Cape Town, and Tamuka Chekero, a Ph.D. candidate, on the news site The Conversation.

“The dominant story of migration in South Africa is that of xenophobia. This is simply not true,” they point out.

An African problem may already have a distinctly African solution – a view of others as a source of strength and comfort.

A South African answer to xenophobia

In recent decades, a rapid rise in migrants displaced by war has tested many host countries. Some, such as Turkey and Germany, have responded generously. Migrants may also boost a labor-short economy. One country that has struggled with an influx of migrants is South Africa. As Africa’s strongest economy, it has drawn people from across the continent seeking safe harbor and opportunity.

This has led to periodic bursts of violence against migrants, including a current wave of xenophobic attacks. Even though their constitution upholds dignity for all, many South Africans see migrants as hindering efforts to lift citizens out of poverty first.

That’s not the case in Giyani, a town near the northern border with Zimbabwe, which is setting an example. There the local citizens and migrant Zimbabweans have forged a seamless community built on social networks that transcend ethnic or national identity. “Peaceful and mutually beneficial relationships between South Africans and migrants can and do regularly exist,” wrote Shannon Morreira, a professor of anthropology at the University of Cape Town, and Tamuka Chekero, a Ph.D. candidate, on the news site The Conversation last month.

“The dominant story of migration in South Africa is that of xenophobia. This is simply not true,” they point out.

Roughly 4 million foreign-born people live in South Africa, according to the most current data. Most are from other parts of Africa where they faced conflict or prolonged economic and political crises. The official statistics also show that immigration, much of which is illegal, has slowed in recent years. But in a country where the unemployment rate has hovered at 35% or higher for decades, foreigners are often accused of stealing jobs and committing crime. One human rights watchdog, Xenowatch, estimates that 623 people have been killed and 123,000 dislodged from their homes since 1994.

The current wave of violence has newly exposed a divide within the ruling African National Congress. A vigilante group calling itself Operation Dudula has taken encouragement from some high-level politicians, including the minister of home affairs, who support anti-migrant policies. President Cyril Ramaphosa has condemned the violence.

In addition, new civil society groups have formed to protest xenophobia. Joseph Mary Kizito, Roman Catholic liaison bishop for migrants at the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference, argues that South Africans must end a feeling of being a separate culture from the rest of Africa. And, as he told the Catholic journal Crux, South Africans should see migrants as able to contribute to a host community.

In towns like Giyani, suspicions of migrants are being dissolved by the process of discovering shared cultural norms. A local hub for commerce, it has attracted Zimbabwean and Mozambican migrants for years. But the political divides that have fueled anti-migrant violence elsewhere in South Africa haven’t disrupted Giyani. Through a mix of assimilation and shared cultural ideas about community, migrants forged social bonds with locals. Churches played a key role in welcoming the foreigners and erasing differences.

“African ideas of making strangers feel at home have been mobilized to good effect,” observed Dr. Morreira. “This has implications for policy and interventions in spaces where xenophobia is rife.” An African problem may already have a distinctly African solution – a view of others as a source of strength and comfort.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Worry less, love more

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Paula Jensen-Moulton

Sometimes love and care for others can seem to go hand in hand with worry. But God is always here to inspire us with peace of mind, wisdom, and guidance, freeing us from disruptive fear and angst.

Worry less, love more

Years ago, a friend was talking to me about her concerns regarding a family member. She said that her worry for this individual was great – for his safety, future, and care. And these constant worried thoughts caused her much angst.

Together we prayerfully addressed this. One thing that we discovered was that the worry and fear were always about this family member’s future: “What will happen to him?” “What if I’m not around to help?” “What if there’s nobody to care for him?”

As we recognized these questions as future-based speculations, staying in the ever-presence of God’s love became key in not entertaining doom-filled thoughts. My friend began to replace the fearful thoughts with thoughts of love – messages from God, divine Love itself, that assured her that Love was capably meeting every concern and providing needed wisdom.

In the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, we find this promise: “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (p. 494). “Worry less, love more” became my friend’s reminder to faithfully turn her thoughts away from anxiety to Love, God. And that included seeing her family member as God knew him – as God’s loved, complete child. She recognized that the love she had for her relative came from God, the true source of all the love we express.

This brought my friend a longed-for freedom. The strong and tender love of our ever-present divine Parent was providing ongoing care and informing her decisions.

And so it has proved, these many years later, and all needs for my friend’s relative have been met, minus the apprehension. God, as infinite Love, is always here to provide for His creation.

As individual spiritual ideas inseparably linked to our Father-Mother God, we have infinite power to accept only the thoughts that come from God. It’s helpful to remember every morning that these uplifting thoughts can be held to throughout the day, defeating and reversing worry.

When we consider that every real, true thought comes from divine Mind, God, we are able to more quickly dispose of fear-based suggestions. We can put off a mortal mentality filled with worries and doubts. We can discern instead the God-given thoughts coming to us as substantial ideas that truly move us in the right direction.

These pure thoughts bring peace and confidence. The Bible gives us this sacred wisdom: “I know the thoughts that I think toward you, says the Lord, thoughts of peace and not of evil, to give you a future and a hope” (Jeremiah 29:1, New King James Version). That kind of inspiring message has all the power of Truth behind it to sweep anxiety away and fill us with the loving expectation and acceptance of Love’s unwavering presence.

Here are some examples to consider of how to identify thoughts that free us from worry and open wide the windows of peace. They are based on seven names for God found in Science and Health.

• Thoughts that come from divine Love are tender and pure, and fill us with the light and power of God’s presence.

• Right ideas have their source in Mind and are intelligent and ready to bless all.

• Thoughts from Truth illumine that which is real and good, and bring healing.

• Messages from Life awaken us to our vitality, joy, and purpose.

• Thoughts from Soul bring spiritual evidence into sharper focus, drawing out grace and beauty in our experience.

• Thoughts from Spirit champion liberty and freedom and reveal our true nature to be spiritual.

• Ideas grounded in Principle reveal the strong foundation of God’s law governing every aspect of our life.

If thoughts don’t meet the criteria above, they aren’t really from God. And to take this concept further, divine Mind is really the only Mind, the one divine governing intelligence imparting all that needs to be known every moment. This brings a calm trust in the unfoldment of ideas that are there for us exactly when needed. Omnipresent Love, all-knowing Mind, is ours to cherish and express and is the sure solution to every discordant or disturbing suggestion that comes our way.

Christ Jesus modeled how to give our full attention to God. And Christ, God’s message of love that is forever here, revealing our true identity as God’s expression, gives us the divine authority to reject all that does not come from God. It gives us authority to cherish and hold in thought all that we know to be valid and worthy.

However worry surfaces, divine Love, your always-available help, is right at hand.

New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Adapted from an article published in the March 14, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Next stop, Rwanda?

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Coming tomorrow: Many are struggling to find bare necessities in Cuba. We explore how the island’s residents show a creative solidarity that is bridging gaps.