- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Did overturning Roe hand Democrats a lifeline? The view from Virginia.

- Eyeing Russia, Lithuania prepped for energy ‘Independence’ years ago

- Her family fled Pakistan for India in 1947. Here’s what they left behind.

- History uncovered: Fossils older than dinosaurs, and a religious refuge

- A modern-day Huck Finn travels the Mississippi on a flatboat

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Reporters on the Job: A bookstore in India serves as refuge

Howard LaFranchi

Howard LaFranchi

As part of my prep for interviewing Indian oral historian Aanchal Malhotra for my story on the 75th anniversary of colonial India’s partition, I purchased a copy of her latest work – 700-plus pages of interviews with the survivors and their descendants of one of the 20th century’s most searing events.

I was still in the impressive tome’s introduction, reading about Ms. Malhotra’s own family’s experience with Partition, when I stopped at this sentence: “When I began these informal explorations, my understanding was limited to the condensed version of events in my school curriculum, and the fact that in 1953 my paternal grandfather had set up a bookshop in Delhi’s Khan Market – then a refugee market, created as a commercial initiative for those who had migrated from the other side.”

A bookshop in Khan Market, I wondered. Could it be?

On my last reporting trip to India in 2019, I’d stayed in a hotel within walking distance of Khan Market, now a collection of mostly tony boutiques and restaurants catering to Delhi’s well-off.

But on one evening stroll, I’d come upon Bahrisons bookshop, and it quickly became a refuge for me – from the oppressive 120-degree Fahrenheit heat Delhi was experiencing, for sure. But it also opened a window into Indian society by the books displayed most prominently, or by the books patrons chose to leaf through. I purchased a couple that offered insight into stories I was doing and led me to several new sources.

So when I reached Ms. Malhotra, before we got down to the business of the interview, I shared my experience with the Khan Market bookshop, and asked if it was her grandfather’s. Indeed it was.

I could hear in her voice her delight. She said my experience with the shop would put a smile on her grandfather’s face, because what I’d found there was what he’d always intended – a welcoming place open to anyone keen to learn new things and to dream.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Did overturning Roe hand Democrats a lifeline? The view from Virginia.

Pundits originally predicted that overturning Roe wouldn’t have much impact on November’s elections. But the summer is suggesting otherwise.

Amid concerns about labor shortages, inflation, gun violence, and other problems, a vast majority of Americans now say the country is on the “wrong track.” That pessimism, along with President Joe Biden’s low approval ratings, has led to grim November election forecasts for Democrats.

But there are growing signs the anticipated “red wave” may be offset by a backlash over abortion. Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, ruling that the Constitution doesn’t ensure a right to an abortion, Democrats have made gains in national polling and are now tied with Republicans on generic ballot tests for Congress.

And while Democrats still face a challenging landscape, results this month on a Kansas ballot measure and two special elections in Minnesota and Nebraska suggest a GOP takeover of Congress is no longer a slam-dunk.

Democratic Rep. Abigail Spanberger, whose Virginia House seat is rated among the most competitive this fall, acknowledges that economic concerns may be top of mind for many voters. But she says abortion will drive some voters to the polls. “Knowing we are in a position where there is a right that has been in place for 50 years and we’re now backtracking – for a certain group, that’s a pretty animating issue.”

Did overturning Roe hand Democrats a lifeline? The view from Virginia.

Wearing a pink linen blazer and her congressional pin on a necklace chain, Abigail Spanberger bounces in the passenger seat of Roy Whitlock’s old truck as the octogenarian farmer drives his congresswoman to the wooded pasture where his cattle are hiding from the August sun.

Mr. Whitlock tells Ms. Spanberger about how his life has gotten harder recently, now that filling up his truck with gas a few times is equivalent to the profit from selling a calf.

The farm is one of several stops on a Field to Fridge Supply Chain Tour, in which Representative Spanberger is meeting with farmers, business owners, and voters in Virginia’s new 7th Congressional District that stretches from the northern suburbs to western farmlands. She has just come from a roundtable where farmers were lamenting the labor shortages impacting almost every area of their work, from truck drivers to veterinarians.

Concerns about labor shortages, inflation, gun violence, democracy, and an array of other issues have led a vast majority of Americans to say the country is on the “wrong track” ahead of this fall’s midterm elections. That pessimism, coupled with President Joe Biden’s low approval ratings and the tendency for post-presidential midterms to swing against the party in power, has led to grim election forecasts for the Democratic Party.

But in late June, following the Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that overturned Roe v. Wade, Democratic strategists and pollsters saw a glimmer of hope. With polls showing the majority of Americans support legal abortion, and protests erupting across the country, some Democrats reorganized their campaign messaging around a woman’s right to choose. Subsequent electoral tests this summer, such as on a Kansas ballot measure and special elections in Minnesota and Nebraska, suggested the Dobbs decision might work to counteract the “red wave” pollsters had predicted this November.

To be sure, Democrats still face a challenging landscape – especially in competitive House races like Virginia’s 7th District. As Ms. Spanberger knows, many voters have serious economic concerns, which are often the top priority when casting a ballot. Abortion is likely to be just one issue among many that voters will consider when they head to the polls. Still, it appears to be giving Democrats a measurable boost, scrambling the political calculus and suggesting a Republican takeover of Congress is no longer a slam-dunk.

“Let’s say, hypothetically, the economy is where it was three years ago, Joe Biden has a 50% job approval rating and the country is humming along – and then we have a reversal of Roe. That could really make a difference,” says Charlie Cook, a political analyst and founder of the Cook Political Report. “But that’s not the circumstance that we have. Will it motivate some people? Yes. But there are so many other things that are going on.”

A shift toward Democrats

Polling suggests the national landscape has improved for Democrats in recent weeks.

Just last week, for the first time this year, Democrats eked out a narrow lead (albeit of 0.1%) over Republicans in FiveThirtyEight’s generic congressional ballot test. And a recent Monmouth University poll found more Americans would prefer Democratic over Republican control of Congress, an improvement from June. Likewise, a Fox News poll from last week found voters evenly split between preferring a Democrat or a Republican candidate for Congress, after Republicans had held a 7-point advantage in May – with the shift coming mainly from women.

“There is a nervousness that’s there among Republican strategists that wasn’t really there 30 or 45 days ago,” says Mr. Cook. “You don’t have to paint them a picture about how this could go the wrong way.”

Democrats have also gained confidence from recent legislative wins – particularly the Inflation Reduction Act, which takes historic steps toward addressing climate change, along with lowering the costs of prescription drugs and raising taxes on corporations. Passage of that bill came shortly after the killing of Al Qaeda’s leader in Afghanistan, gas prices dropping below $4 a gallon, and a strong jobs report, rounding out a spate of positive news cycles for the Biden administration.

But the biggest source of optimism for Democrats unexpectedly came from Kansas, where almost 60% of voters in that largely conservative state voted earlier this month against removing abortion protections from the state constitution, with higher than expected turnout in suburban and rural areas alike. “Kansas is the earthquake that is going to rattle every assumption about what is going to happen this fall,” Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Chairman Sean Patrick Maloney told The Washington Post.

Then last week, in two special U.S. House elections in Minnesota and Nebraska districts – both areas former President Donald Trump had won by double digits in 2020 – Republican candidates won by smaller margins than anticipated, with Democrats over-performing in larger, suburban districts.

“There’s still time for things to snap back before November, but we’re no longer living in a political environment as pro-GOP as November 2021,” Cook Political Report’s House editor David Wasserman tweeted on Wednesday.

GOP strategists are quick to point out that a ballot measure on one specific issue is very different from a multifaceted congressional election in which voters are weighing candidates and a variety of issues. They say the abortion ruling may help Democrats cut in on Republicans’ margins somewhat, but not enough to pull off outright wins.

“People can latch onto anything for hope,” says Matt Gorman, former communications director for the National Republican Congressional Committee and current vice president at Targeted Victory. “The midterms are going to be dominated by the economy and inflation. That’s what people are feeling right now, and in every poll that’s what they’re caring about.”

To Mr. Gorman’s point, the recent Monmouth University poll found that 24% of voters ranked economic policy as the most important issue in a congressional vote choice, followed by gun control policy (which has almost doubled in importance over the past three months) and abortion policy (which has actually fallen by 8 percentage points) tied at 17%. In third place is health control policy, followed by climate change and then immigration.

Ms. Spanberger recognizes the array of issues voters are considering.

“In a room full of people you might have, you know, 10 there who were there because they care about democracy-related issues and they’re worried about the fact that so many colleagues wouldn’t certify the election. You might have some folks who are just like, ‘You are the ones voting to lower prescription drug costs and that’s my issue,’” Ms. Spanberger tells the Monitor after her truck ride with Mr. Whitlock.

“Then there’s going to be people who are motivated because of the Dobbs decision,” adds the congresswoman. “So I don’t think it’s, like, the singular animating issue. But from what I’ve witnessed thus far, there are people for whom life is OK. Yes, maybe gas is more expensive and there are challenges here and there, but knowing we are in a position where there is a right that has been in place for 50 years and we’re now backtracking – for a certain group, that’s a pretty animating issue.”

View from a competitive House district

Ms. Spanberger’s reelection campaign may be one of several House races where this is particularly so. Holding one of the more competitive seats this fall, Ms. Spanberger is running in a new 7th District that was redrawn to include both rural and suburban areas around Culpeper and Fredericksburg. Her campaign highlights the two-term congresswoman’s moderate bona fides: She was recently ranked the fifth most bipartisan member of the U.S. House by The Lugar Center.

Her Republican opponent, Yesli Vega, a Prince William County board supervisor and former police officer in northern Virginia, has drawn national attention as one of several Republican Latina candidates running for office this year. She spoke onstage at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) earlier this month about the GOP’s ability to attract new support among minority voters.

But Ms. Vega also made news earlier this summer when, in response to a question about state-level abortion restrictions, she responded by questioning a woman’s ability to get pregnant following a rape. Ms. Vega and her campaign did not respond to the Monitor’s repeated requests for comment.

Steve Mourning, chair of the Culpeper GOP and a software developer, says he’s feeling a level of energy among Republican voters comparable to 2020, when Republican Nick Freitas lost to Ms. Spanberger by less than 1 percentage point.

“Abortion just doesn’t seem to be that big of a factor in the race. Folks are suffering from inflation and gas prices,” says Mr. Mourning, adding that a few of the Republican committee’s retired members stopped coming to meetings in person due to the cost of gas.

But Jen Heinz, co-chair of the neighboring Orange County Democrats, says the issue of abortion has been coming up regularly when she is out canvassing.

“In the past couple of weeks, you can really feel the uptick in support,” says Ms. Heinz.

At the county fair in late June, shortly after the Supreme Court ruling came down, Ms. Heinz says three young women approached the Orange County Democrats’ booth to ask about Ms. Spanberger’s position on abortion. After Ms. Heinz responded that the congresswoman had voted to codify a woman’s right to an abortion into law, one of the girls asked how she could register to vote.

“Here is a young woman who has never voted before,” says Ms. Heinz, “but feels motivated to fill out the form.”

Eyeing Russia, Lithuania prepped for energy ‘Independence’ years ago

Before Russia waged war in Ukraine and threatened Western energy supplies, Lithuania steeled itself against such aggression – shown by its acquisition nearly a decade ago of a ship called Independence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Long before the West woke up to Russian President Vladimir Putin as a threat, 3 million-strong Lithuania had always had eyes on its gargantuan neighbor. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Lithuanian leaders boldly declared that Mr. Putin had already started waging war on Europe, a claim that pacifist ears in the West didn't hear.

Now a series of policy decisions made over decades, based on the principles of preserving democratic freedoms, looks prescient.

Key among those was commissioning the Independence, a massive processing terminal for liquefied natural gas, which went into operation in 2014. It immediately started saving money for Lithuania, which had been reliant on Russian gas. Today it has allowed the country to stop Russian energy imports completely and help other European Union nations end their dependence on the Kremlin.

Vilnius has also set precedent for the bloc with its recognition of Belarusian pro-democracy opposition and Taiwan’s representative office. While Western Europe might have previously reacted to those decisions with skepticism, Lithuania is now able to start driving select parts of the EU agenda with its approach.

"We understand it in a very simple way: If autocracies are not stopped in the very beginning then they become international aggressors," says former Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius.

Eyeing Russia, Lithuania prepped for energy ‘Independence’ years ago

As Europe scrambles to defend itself against Russian aggressions, tiny Lithuania is reaping the benefit of cleareyed moves made more than a decade ago. That was when it commissioned the Independence, a massive floating vessel and processing terminal for liquefied natural gas.

Linas Kilda was the Lithuanian project manager tasked with overseeing ground-to-sea pipeline connections for the Independence. It was the early 2010s, and public sentiment was sharply divided. Yet success would mean Lithuania could eventually pick and choose among energy suppliers. At that time, Russia supplied the vast majority of Lithuania’s energy needs while playing politics with prices.

“We were paying the highest prices in the EU,” says Mr. Kilda, recalling the years just before the terminal opened in 2014. “My grandparents survived the deportation to Siberia during Soviet times, and they always dreamed of an independent Lithuania.”

Indeed, long before the West woke up to Russian President Vladimir Putin as a threat, 3 million-strong Lithuania had always had eyes on its gargantuan neighbor. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Lithuanian leaders boldly declared that Mr. Putin had already started waging war on Europe, a claim that pacifist ears in Germany and the West didn’t hear.

Today, a series of policy decisions made over decades, based on the principles of preserving and promoting democratic freedoms – including commissioning the Independence, but also the recognition of Belarusian pro-democracy opposition and Taiwan’s representative office – looks prescient. While Western Europe might have previously reacted to those decisions with laughter, skepticism, or frustration, Lithuania is now able to start driving select parts of the EU agenda with its approach.

“We always are fighting for spread of democracy and human rights because of our neighbor,” says Andrius Kubilius, who served as prime minister when the Independence was ordered in 2011.

“Thirty kilometers [18 miles] from Vilnius is a border where the democratic continent ends and you have Russia and Belarus – totalitarians. We understand it in a very simple way: If autocracies are not stopped in the very beginning, then they become international aggressors, like what happened with Putin.”

“Counting butterflies during a war”

Every week for more than two years in the early 2010s, Mr. Kilda oversaw pipeline construction for the Independence on the Baltic coast as a then-project manager for Lithuanian LNG operator Klaipedos Nafta. It required sacrifice, spending long days apart from his family in Vilnius, the capital, but he’d signed on not only for professional but also for personal reasons.

“One of the key drivers for me joining this project was to help my country become independent,” says Mr. Kilda. The Soviet Union had occupied Lithuania for 50 years beginning in the 1940s, and the forced deportations and resettlements of tens of thousands of Lithuanians made an indelible mark on many a family history, including Mr. Kilda’s.

Should Lithuania have its own LNG terminal – which re-gasifies a supercooled form of natural gas – vessels from any country could slide into Lithuania’s port. This would break Russia’s stranglehold on supply.

Russia enjoyed a near monopoly on oil and gas supplies to Lithuania, and it had been weaponizing energy in negotiations with the country, which had only declared independence from Moscow in 1991. “Russia started using energy as a weapon against Western Europe only one year ago, but Eastern Europe was under fire all the time,” recalls Albinas Zananavicius, the country’s vice minister of energy. Meanwhile, Russian state media was dubbing Lithuania a “dying young democracy” doomed to “energy destitution.”

Against this backdrop, the government instituted a tight deadline for the Independence to come online. Major milestones aside, countless minor details needed attending to.

The Curonian Spit, a UNESCO World Heritage Site whose sand dunes curve along the Baltic Sea from the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad in the south to Lithuania in the north, needed special attention. One part of the spit harbored spawning fish. A nesting habitat for sea gulls needed encircling with a tent, recalls Mr. Kilda. Local citizens needed to be reassured that having massive amounts of LNG in their backyard wouldn’t pose a danger.

“We were counting butterflies during a war,” says Mr. Kilda, recounting a running joke of the day. Even the colors of the ship came under fire. “Some guys asked why the Independence is in Russian colors,” he says. “But white, blue, and red has the lowest visual impact. So it’s not so visually disturbing.”

Finally, in 2014, the tankerlike Independence pulled into the port of Klaipėda with Lithuanian flags waving and a national audience on television. The impact on gas prices was immediate: They plummeted. The week prior, Lithuania was paying on average €8 ($8.20) more per kilowatt-hour than Western Europe; since then, the country has enjoyed an estimated savings of €150 million every year as the Independence forced Russia to compete with other natural gas suppliers, estimates Mr. Kilda’s team.

Today, ships carrying LNG from Norway, the United States, and a multitude of other sources pull up alongside the Independence to transfer their precious cargo. Lithuania was the first EU country to stop buying Russian gas after the war began. And now energy companies from other countries have come calling. “The Independence has been asked after as a model of independence for not only Europe but Asian countries, and even some smaller countries which are also struggling with having a single supplier,” says Mr. Kilda.

“We were always the freedom fighters”

Lithuania’s embrace of independence from the dictates of larger authoritarian countries doesn’t end at its own borders. Last fall, the government allowed Taiwan to open up a representative office in Vilnius and dubbed it of “Taiwan” rather than of “Chinese Taipei,” as many countries do in the ongoing quest not to irk China.

“It’s our right to call the office whatever we want,” says Mr. Kubilius, the former prime minister. “China needs to understand that the world during the last several hundred years was led by democracies.”

China promptly downgraded diplomatic relations and also halted certain Lithuanian imports such as beef and dairy. But the European Union – which first met Lithuania’s move on Taiwan with skepticism and frustration – ultimately rallied behind Lithuania and filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization.

“Bravery comes with particular costs,” says Margarita Šešelgytė, director of the Institute of International Relations and Political Science at Vilnius University. “China plays under the carpet and informally we receive praise for what we’re doing, but formally no one is following.”

That said, Taiwan is also now committing to new investments in Lithuania.

Lithuania has also offered refuge to the pro-democratic opposition of Belarusian leader Aleksander Lukashenko, and vocally supported Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement, even while other countries demurred from provoking Russia and China.

Perhaps it’s Lithuania’s “fighting spirit,” says Mr. Zananavicius, the Lithuanian vice minister of energy, who recalls that when the Independence was first being discussed, people were “laughing at us.”

“But if we’d listened, our independence wouldn’t have materialized. Our struggle was difficult, but we were always the freedom fighters. It’s a little bit in the blood.”

“The freedom to do whatever we wanted”

The fight for freedom seems to be something Lithuanians take pride in, and declare it’s worth paying for. Even though subzero temperatures are a fact of Lithuanian winters, having the right sources of energy is as important as the cost of the winter heating season.

“I was brought up kind of hating Russia,” says Arunas Smalskys, an information technology engineer who lives in Vilnius. “So independence from Russian oil, Russian gas was always a decision my parents wanted our government to make. The freedom to do whatever we wanted.”

Eugenja, a housecleaner who lives in Vilnius and asked that her last name not be used, remarks that her heating costs for the upcoming season will be nearly double last year’s due to Europe’s energy crisis, but it will be “worth it.” “It’s better to have our own supply, rather than give our money to other countries.”

And the Independence now sets up Lithuania to export energy, especially as Russia threatens the supplies of EU neighbors that still rely heavily on its energy.

In Vilnius, exhaust chimneys stand idle at a massive power plant run by state-owned energy company Vilnius Šilumos Tinklai, which supplies most of Lithuania’s heat. The company burns biomass and also distributes LNG. Come winter, the chimneys will be working overtime, especially as Mr. Putin has pinched off gas to Poland, Bulgaria, Finland, the Netherlands, and Denmark. Prices are skyrocketing and countries are scrambling to stockpile.

“We’ve already secured the necessary gas for winter, but we have to feel the responsibility not only for ourselves,” says Paulius Martinkus, Vilnius Šilumos Tinklai’s chief strategy officer. He and his employees are preparing for the possibility that they might need to burn fuel oil to create enough energy supply to help needy neighbors. “We can burn gas and let the neighbors freeze, but it’s not the right approach. We have a values-based approach.”

At the plant’s main switchboard, Kazimieras Paulavicius recalls Lithuania’s long fight for independence from Russia. “Tanks were rolling down the streets at night, and I felt despair and concern,” he says. Today he works with lights off when possible, having long understood the link between energy and values.

“Energy independence is our weapon,” says Mr. Paulavicius, who has worked in the industry for nearly 50 years. “It means we can buy and sell energy, choose different fuels, have flexibility.”

That flexibility, says Mr. Martinkus, will now benefit others. “We are mobilizing and basically living to values, and we are getting employees on board as well. We want to be part of Europe, and we feel the responsibility of being part of Europe. It’s not only about taking, it’s also about giving.”

Ieva Balsiunaite supported reporting for this story.

Commentary

Her family fled Pakistan for India in 1947. Here’s what they left behind.

Grappling with her family’s actions during Partition helped our contributor discover a new well of compassion – a quality needed now more than ever.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Noor Anand Chawla Contributor

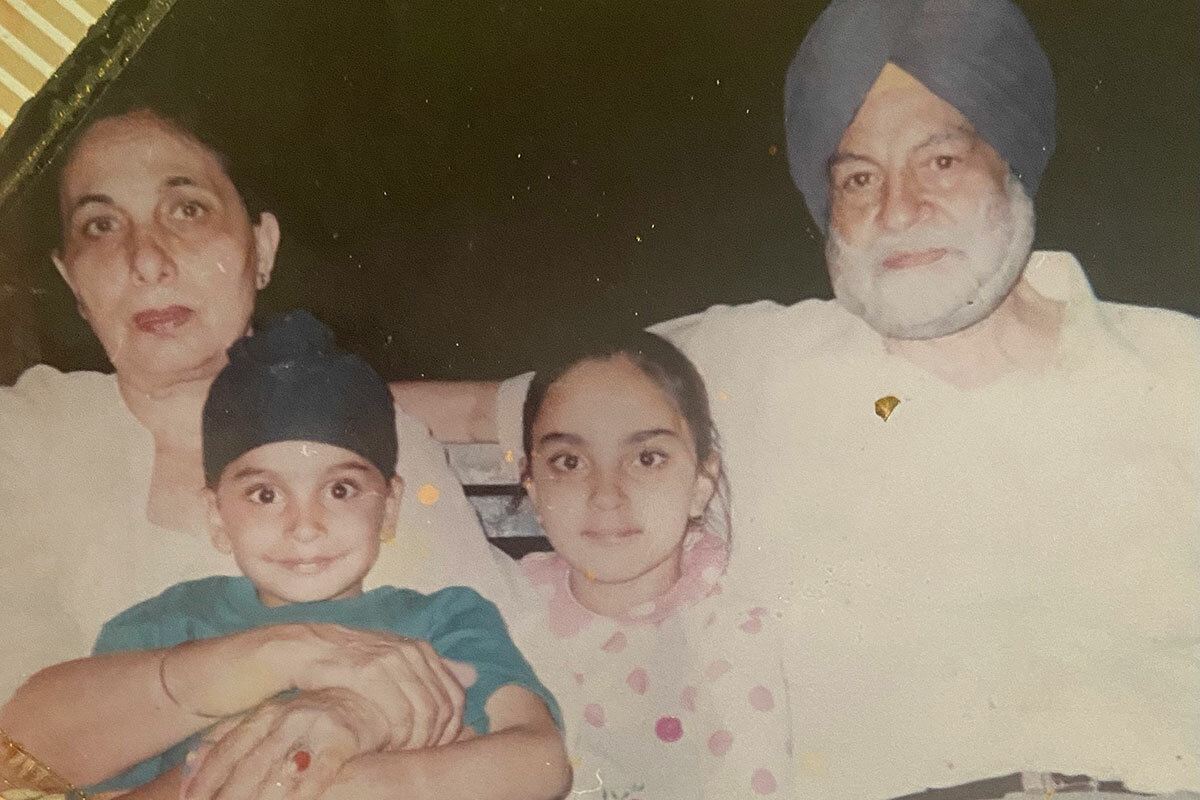

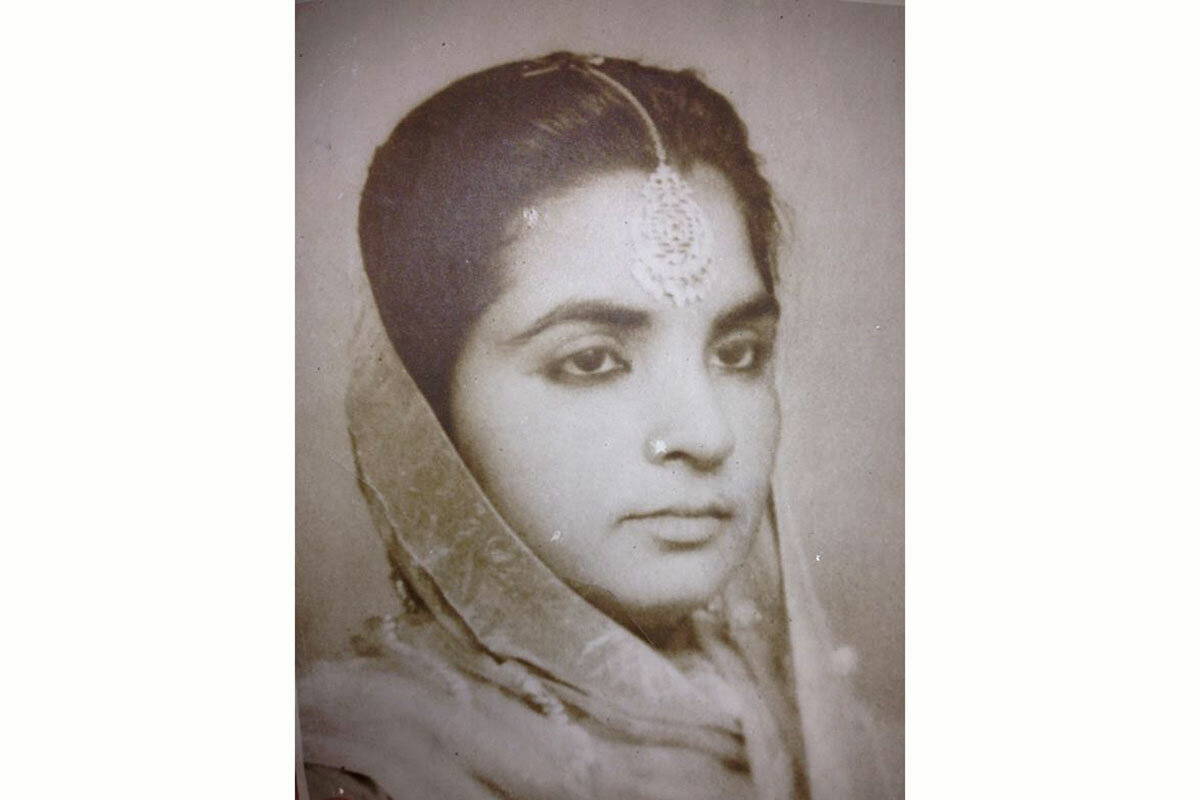

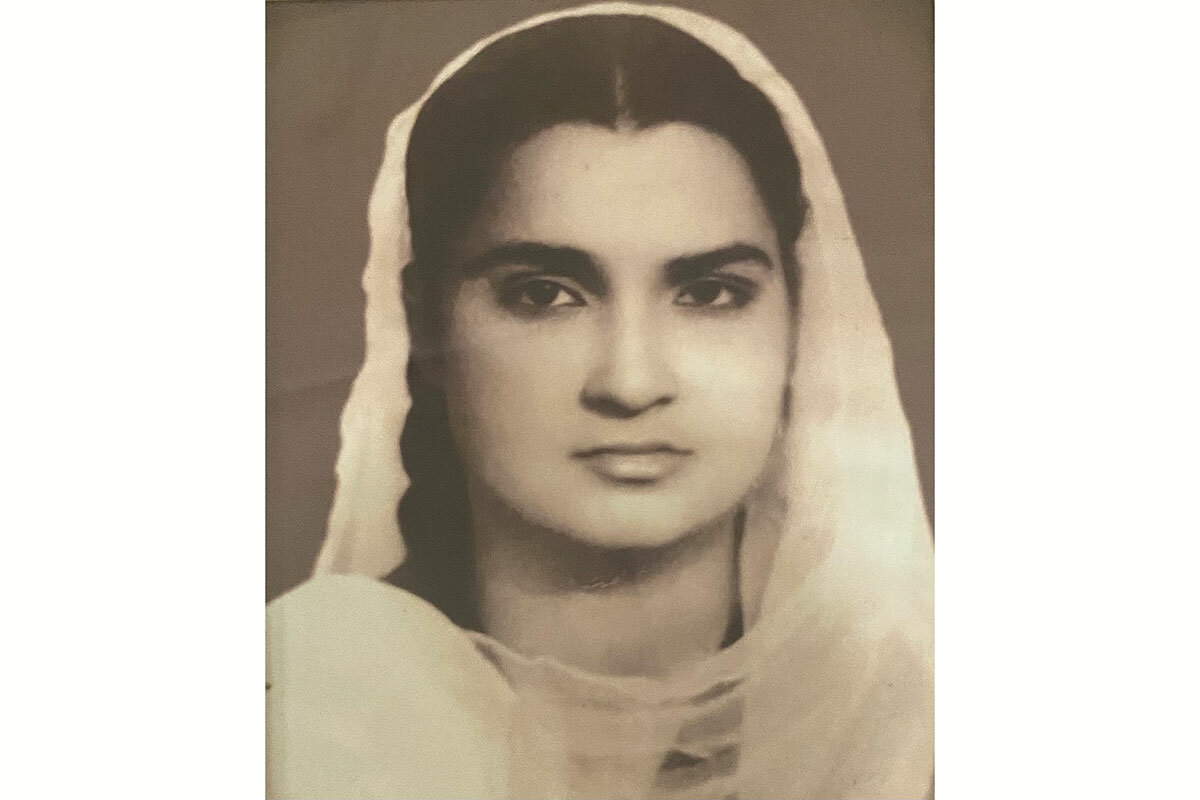

As a third-generation Sikh migrant born and raised in Delhi, I was always aware that during Partition members of my family had crossed the border from newly created Pakistan to lay down roots in India. But it wasn’t until my late 20s that I learned of a distant aunt who’d been abandoned during her family’s chaotic evacuation in 1947. The year after she was left behind, a family friend spotted her alive and apparently well in Pakistan. She had married a local and converted to Islam. But instead of celebrating this news, her siblings and parents declared her dead to preserve the family’s honor.

When I first heard this story, I was aghast. In the years that followed, however, marriage, motherhood, and a change in career from being a lawyer to a writer helped me look at things differently.

Faced with the loss of everything they held dear, including their homeland, my family perhaps should not be blamed for attempting to preserve the one thing they had control over – the legacy of their religious leaders, who fought back against forced religious conversion and called on followers to do the same.

Though I cannot condone the behavior of my elders, I find it increasingly easy to empathize with them.

Her family fled Pakistan for India in 1947. Here’s what they left behind.

Every August, my countrymen and those of our neighbor Pakistan collectively rejoice.

After all, our shared Independence Day – testimony to the long and arduous struggle for independence from our British colonizers – is just cause for celebration. Yet, for a sizable section of the populace, this occasion is marred by the memory of the traumatic event that occurred alongside it: the brutal and reckless partition of the subcontinent into two nations, Muslim Pakistan and secular India, in August 1947.

Growing up, I was drawn to the Partition portrayed in literature and movies. I knew millions were displaced or killed by the communal violence that erupted across the subcontinent, particularly in places like Punjab, where my family is from, which was divided by the new border.

Yet, as a third-generation Sikh migrant born and raised in Delhi, I viewed Partition as a largely abstract concept. I was aware that certain members of my family had crossed the border to escape riots and lay down roots in Indian soil, but I did not understand the details of this journey – or how their discovery would force me to expand my worldview in ways that were uncomfortable but ultimately enriching.

It wasn’t until 2017, when the 1947 Partition Archive released an interview with my paternal grandfather, that the stark realities of Partition came into focus for me. As I read my grandfather’s account of being a young army officer watching trains brimming with bodies of dead Muslims move toward Pakistan, I wondered why we never spoke about this incredibly difficult period in his life.

Perhaps in my naiveté, I didn’t know to ask, and in his reticence, he didn’t think to tell.

His story inspired me to delve deep into my family’s Partition experience, and I soon learned that my maternal grandmother, or Naniji, had migrated with her family from the West Punjab city of Rawalpindi to Delhi in 1947.

Like my grandfather, Naniji had died by the time I started investigating my family history, so it was her son, my uncle, who shared her story with me.

As religious rioting began to spread throughout newly created Pakistan, Naniji’s father, who held an exalted position as the local bank manager, sent his wife and their brood of eight young children; one newly married daughter, Jeet Kaur; and the daughter’s husband to Delhi while he stayed behind to wrap up some business affairs.

At the station, as the family was boarding the train, a group of hooligans kidnapped Jeet Kaur. Her husband beat a quick retreat, while the younger children, traumatized at seeing their beloved sister left behind, created a ruckus – but to no avail. Every person on that train was mourning a deep loss; the cries of aggrieved children were easily ignored, and soon buried in the silence that follows the trauma of survival.

According to my uncle, a family friend who worked as a government pilot spotted Jeet Kaur the following year. He reported that she had converted to Islam, married a local, and seemed to be expecting his child.

Instead of celebrating this news, Jeet Kaur’s stoic mother – my great-grandmother – declared her daughter dead in an effort to preserve the family’s honor. With time, the siblings, too, chose to believe their sister dead.

Though the family was successful and happy by all outward appearances, the strain of losing their sister revealed itself in the acute mental health issues of the oldest brother, and in the vitriolic conversation of the younger brothers whenever Muslims were mentioned.

It was only years later, when their children – second-generation migrants – learned the facts about Jeet Kaur, that her “death” was challenged in any way. The more forward-thinking youngsters were upset, but felt powerless to do anything about it.

By the time my generation arrived in the 1980s and ’90s, the “otherness” of Muslims had ceased to evoke such serious negative emotions. When I moved to London to pursue a master’s degree in the early 2010s, I felt impervious to religious and national differences. There, I made friends from both sides of the border, bonding over our shared culture, language, and foods. We created our own narrative, and it effectively put the Partition in a place that seemed almost fictional.

Years later, when I learned of my distant aunt, I was aghast. I had read novels about women being killed by their own family to prevent them from being raped by members of another faith, or of women being left behind and declared dead to maintain the family’s honor. It seemed inconceivable to me that the love for a daughter or sister could so easily be cast aside in the face of saving perceived family honor. But now, my own family was guilty of this injustice.

At first, I was extremely upset, and questioned my uncle. Where did the pilot find her? Why didn’t anyone in the family go back? But he was merely the messenger – most of my grandparents’ generation were gone, and the time for debate had passed.

In the years that followed, however, I learned to look at things differently. Marriage, motherhood, and a change in career from being a lawyer to a writer helped me open my worldview to other perspectives.

It eventually dawned on me that the act of abandoning this young girl in Pakistan was a result of centuries of social conditioning, dating back to the origin of the Sikh religion itself. Our 10th and final Guru, Gobind Singh, formed a military sect known as the Khalsa – literally “the pure” in Punjabi – which was called to fight the forced conversions of Hindus and Sikhs into Islam by 17th-century Mughal rulers. The Khalsa chose death over conversion, exemplified in the story of the Guru’s two younger sons, ages 9 and 6, who chose to be bricked alive over converting. Their sacrifice remains an inspiration to Sikhs today.

Faced with the loss of everything they held dear, including their homeland and family, these hapless children and their lonely mother perhaps should not be blamed for desperately attempting to preserve the one thing they had control over – the legacy of their Gurus, which was their very identity.

At the same time, I cannot judge my aunt for choosing to convert. I would also like to believe she lived a better life than she might have with her original husband, who abandoned her at that train station back in 1947.

Though I cannot condone the behavior of my elders, I find it increasingly easy to empathize with them. I can only hope I’ll never have to make the sorts of decisions my grandparents and great-grandparents did, or face such a sudden, monumental loss. I can never know how I would react in their position.

What I can do is try to foster a more inclusive worldview, for myself and my children, in which everyone is worthy of understanding.

Seventy-five years on, as the deeply embedded religious intolerance in my own countrymen begins to rear its head once again – this time buoyed by a Hindu nationalist political agenda and fueled by fears of forced conversions – this capacity for compassion is more important than ever. Isn’t that what democracy, of which we so proudly proclaim ourselves the largest proponent, is all about?

Noor Anand Chawla is an independent journalist based in New Delhi. She contributes to various publications and blogs at www.nooranandchawla.com.

Points of Progress

History uncovered: Fossils older than dinosaurs, and a religious refuge

In our progress roundup, discoveries in both Brazil and Turkey were surprising in their vastness, providing paleontologists and archaeologists with a wealth of opportunities to learn.

History uncovered: Fossils older than dinosaurs, and a religious refuge

Discoveries of an old human civilization and ancient animals and plants are enriching knowledge of life on Earth. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom is developing a new environmental curriculum to help safeguard the planet.

1. Brazil

Brazilian paleontologists rediscovered a mother lode of fossils that had been lost for decades. The incredible fossil site was initially discovered in 1951 in the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul. But without a description of the exact location, the fossils may have remained hidden if landowner Celestino Goulart hadn’t been curious about the fossil of a fish on his grandfather’s mantel that he’d heard came from his backyard.

A research team has since dug 6 feet into the ground, uncovering hundreds of fossils so far that range from pteridophyte vegetation to mollusks and ancient fish from the Permian period, a time that led to a mass extinction and paved the way for the dinosaurs. Scientists draw parallels between that period and today.

“While what we’re going through now is a result of human behavior, the mechanisms of extinction are very similar to those that happened during the Permian period,” says paleontologist Felipe Pinheiro. “We are interfering in the same biogeochemical cycles – the carbon cycle, the nitrogen cycle – that during the Permian period, because of natural factors, caused the death of almost 90 percent of species. So when we study this extinction, we’re studying the present day.”

Source: National Geographic

2. United States

The number of young people at Hawaii’s juvenile detention facility has fallen dramatically. Minors who end up at the Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility are some of the most vulnerable and high-risk youth. In 2014, there were over 100 youths at the facility. Thanks to extensive reforms, there were only 15 young people in incarceration in June – and no girls.

Many young people land in prison for low-level offenses and have histories of abuse or poverty. Hawaii’s success does not mean the state has fully solved the problems facing youth, but reflects a key shift toward trauma-informed care.

“What I’m trying to do is end the punitive model ... and we replace it with a therapeutic model,” said Mark Patterson, administrator of the correctional facility. “Do we really have to put a child in prison because she ran away? What kind of other environment is more conducive for her to heal and be successful in the community?” Nationally, incarceration rates for young people dropped by two-thirds between 2000 and 2018, according to the justice reform initiative Square One Project.

Sources: Hawaii News Now, The Washington Post

3. United Kingdom

Aspiring to be a world leader on climate change, the U.K.’s Department of Education is creating a new national curriculum for secondary school students to inspire environmental responsibility. The natural history course will focus on three main sustainability issues: local wildlife, environmental field studies, and the impact of human development on the natural world. The course will be ready for students by 2025.

Nearly 60% of young people across the U.K. and nine other countries reported feeling very worried or extremely worried about climate change, according to a 2021 survey. “We can make studying the natural world as much a part of school life as maths and English, establishing it as a foundational subject,” wrote environmentalist Mary Colwell, who first proposed the idea of a curriculum in 2011. Some educators say climate change should be taught across subjects, not siloed into its own course; other advocates are pushing for a more robust environmental curriculum earlier on in the school system.

Sources: The Guardian, BBC Wildlife Magazine, Schools Week

4. Turkey

Researchers are uncovering details about civilization in ancient Turkey, as they explore a sprawling city below modern-day Midyat. An underground tunnel leading to the town of at least 74 acres was discovered during a restoration project of local homes in 2020. The site is thought to be a former refuge for Christians and Jews, who were persecuted by the Roman Empire in the first century. Researchers have turned up coins, lamps, and silos for food, oil, and drinks among the homes carved out of limestone, where an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 people lived between the first and sixth centuries. One rock wall bears an engraved Star of David that may have been part of a synagogue. Archaeologists know of several dozen other underground cities across the country, but none as large as this discovery, being called Matiate. Only around 5% of the town has been excavated so far.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

5. Mozambique

A national park in Mozambique now offers a haven for rhinos, formerly extinct in the region. Zinave National Park became a protected area in 1972, but a civil war from 1977 to 1992 decimated the land. Following years of other rewilding and restoration efforts, conservationists recently succeeded in transporting 19 white rhinos from neighboring South Africa to Zinave. The rhinos traveled over 1,000 miles in the longest rhino road transfer yet completed.

An estimated 8,000 rhinos have been killed by poachers in southern Africa in the past decade. Reintroduction efforts give species a better chance at survival by providing a habitat for future generations – a healthy female rhino calf was born in June. The team intends to release 40 rhinos in Zinave over the next two years, to join over 2,400 animals from 14 species already introduced, including leopards, wildebeests, and hyenas. Zinave is part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park, linking national parks in Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe – an important initiative for conservation, tourism, and local job creation.

Reuters, Peace Parks Foundation

Book review

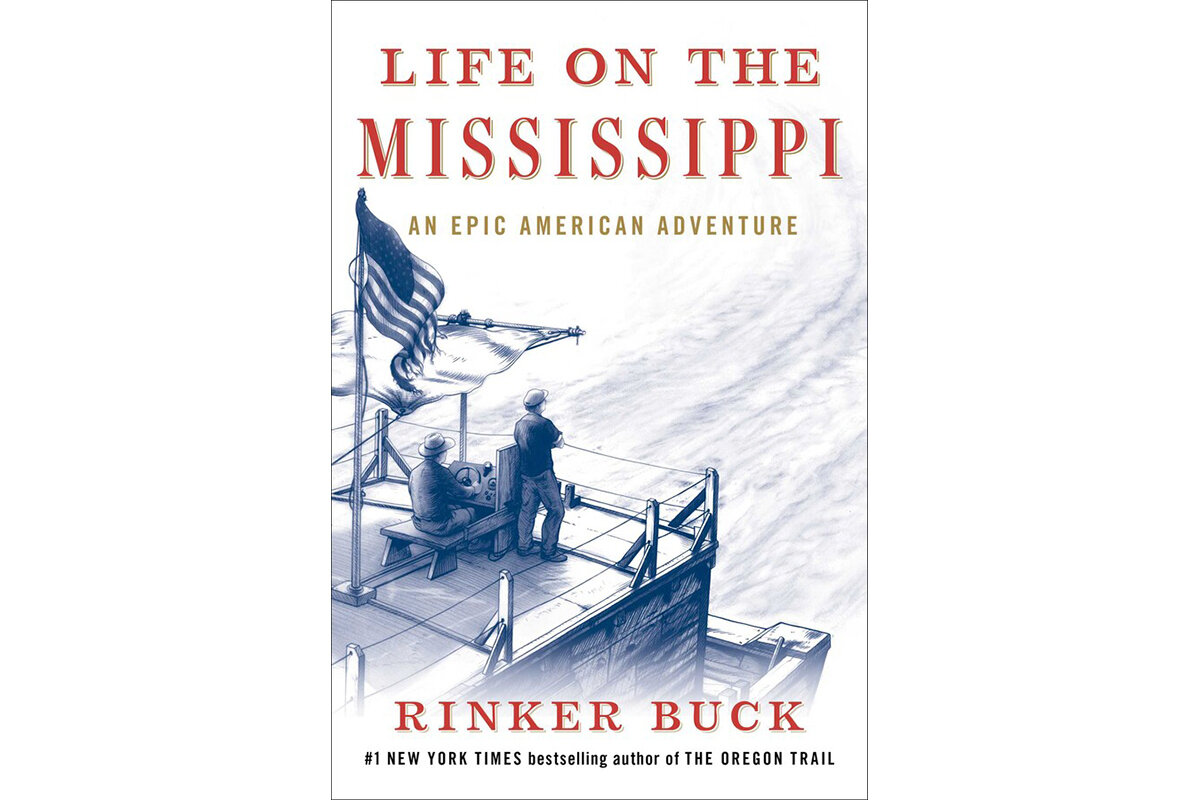

A modern-day Huck Finn travels the Mississippi on a flatboat

What does it take to see a project through? Journalist-adventurer Rinker Buck drew on perseverance and courage to safely pilot a flatboat down the Mississippi River – making connections with people and America’s past.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Terry W. Hartle Contributor

Having played a critical role in westward expansion, the mighty Mississippi River exerts a pull on the American imagination.

Flatboats were the vessels of choice for 19th-century inland shipping, carrying people, including settlers, and goods such as tobacco and cotton.

Rinker Buck, a journalist with a deep interest in history and a love of adventure, commissioned a boat builder to construct an updated replica of a flatboat, hired a crew, and set off in 2016 on a 2,000-mile journey from Pittsburgh to New Orleans on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

He documents the journey in “Life on the Mississippi: An Epic American Adventure.”

The book is both a travelogue and a sometimes sobering history lesson. Buck recounts the central role the Mississippi River played in the Trail of Tears – the expulsion of more than 100,000 Native Americans from the Deep South. He also writes about how flatboats were used to move at least 1 million enslaved people from the tobacco fields of Virginia to cotton plantations in the Mississippi Valley.

While the book is largely about the adventures Buck and his crew experienced, he writes compellingly about the need to look at all sides of the nation’s complicated past.

A modern-day Huck Finn travels the Mississippi on a flatboat

In the early years of the 19th century, vast numbers of small wooden boats plied the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Carrying goods to market and settlers to the lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains, these vessels launched America’s western expansion. The boats were known by many names but, because they had a flat bottom and a shallow draft, they were commonly called “flatboats.” After the Civil War and the rapid expansion of railroads, they gradually disappeared.

Rinker Buck, a journalist with a deep interest in history and a love of adventure, became fascinated by this little-remembered chapter of American history. He decided that the best way to understand this era would be to build a boat, hire a crew, and travel these legendary rivers himself. He documents the journey in “Life on the Mississippi: An Epic American Adventure.”

He engaged a small, family boatbuilding company in Gallatin, Tennessee, to build the vessel, which was not an exact replica of its forerunners. For starters, it had a motor. It also had modern maps, GPS, a marine radio, a lighted magnetic compass, and an electric bike for getting supplies while docked. He named it Patience and declared, “She was as sturdy as a Roman galleon and looked as jaunty as a ... monster truck.”

However, the journey did not start well. He hired a semi-trailer to truck the Patience to the launch site in Pennsylvania but the 550-mile-journey over interstate highways was “an epic fiasco.” The truck suffered a dozen blown-out tires along the way and Buck wondered if he should have named his flatboat Calamity.

Buck was well aware that the trip would be dangerous because the river is more treacherous today than it was 200 years ago. There are locks, dams, sandbars, cement revetments, rock jetties, and mountains of floating debris to avoid. Submerged obstacles like boulders and logs could have easily ripped out the ship’s hull.

More important, thanks to navigational improvements designed to facilitate barge traffic, the river current is much faster today than it used to be. On any given day along the lower Mississippi, there are “at least 820 tugs pushing barges and the typical fifteen-barge string weighs over twenty-two thousand tons, making it virtually impossible for them to alter course quickly,” he writes. And the last 50 miles of the Mississippi River before New Orleans is “essentially a commercial sea-lane, congested with large oceangoing vessels.”

There was no shortage of people telling him that he was nuts. His brothers tried to dissuade him, saying, “You’ll sink the boat in the first storm.” During the trip, with the Patience moored at docks near towns, locals came down to see the boat. They were appalled that the crew wasn't carrying firearms. Buck writes, "Upriver, the [white] off-duty cops ... implored us to get weapons because the Blacks in Vicksburg and Baton Rouge were going to pour over the banks to rob the boat. Downriver, the Black kids were convinced that the rednecks were going to get us. The race-blind solution for all was the same: America, Get Guns."

Instead, the people the crew met along the way were overwhelmingly welcoming and eager to be helpful. In a time of intense political polarization, it’s uplifting to see so many who were willing to help a modern pilgrim on his journey.

Ultimately, the book is both a travelogue and an engaging history lesson about America’s westward expansion after the Revolutionary War. Of course, the history of antebellum America was also “profoundly tragic.” Buck recounts the central role the Mississippi River played in the Trail of Tears, which saw the expulsion of an estimated 100,000 Native Americans from the Deep South. Later, he writes despairingly of the way flatboats were used to move at least one million enslaved people from the tobacco fields of Virginia to cotton plantations in the Mississippi Valley under horrific conditions. Without river transport, such vast movement of human beings would not have been possible.

After four months and 2,000 miles, Buck navigated the jam-packed Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and reached his destination, where he felt “exhaustion, exhaustion, elation, elation.” He also reported being “just maybe more experienced, and a little vain about proving that I could handle a boat.”

Buck points out that he should have discounted the warnings of doom and trusted his own instincts and skills and those of his crew. And he was reminded once again that American history is a story of good and bad, inspiration and shame. He repeatedly talks about the need to look at all sides of the nation’s long and complicated past.

It’s a mark of Buck’s ability to write engagingly of his journey that many readers will conclude that a trip down the Mississippi would be a romantic adventure and a wonderful chance to learn about America’s history. But it’s equally the case that few, if any, of them will want to make the trip by flatboat.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Hidden hand of calm in Iraq

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

As Americans know well, when angry protesters forcibly occupy the national legislature, violence is all too possible. Yet in Iraq, whose democracy was planted by the 2003 U.S. invasion, a similar protest in Baghdad over recent weeks has been relatively peaceful. One reason may be the quiet influence of the country’s most respected religious leader, top Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani.

For 10 months, Iraqi politics has been in a tense stalemate following an inconclusive parliamentary election. No party won enough votes to form a government. The standoff – between two dominant alliances representing the country’s majority Shiites – has been fought behind the scenes as well as in dueling protests in the legislative building and the streets. Fears of a civil war are high with a potential to disrupt the Middle East.

In recent days, Mr. Sistani reportedly met with the leader of one political bloc, firebrand Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. His bloc, which rejects meddling by Iran, won the most seats in the election. The meeting fits Mr. Sistani’s long insistence that Iraqis act responsibly as a nation to avoid the “abyss of chaos and political obstruction.”

Hidden hand of calm in Iraq

As Americans know well, when angry protesters forcibly occupy the national legislature, violence is all too possible. Yet in Iraq, whose democracy was planted by the 2003 U.S. invasion, a similar protest in Baghdad over recent weeks has been relatively peaceful. One reason may be the quiet influence of the country’s most respected religious leader, top Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani.

For 10 months, Iraqi politics has been in a tense stalemate following an inconclusive parliamentary election. No party won enough votes to form a government. The standoff – between two dominant alliances representing the country’s majority Shiites – has been fought behind the scenes as well as in dueling protests in the legislative building and the streets. Fears of a civil war are high with a potential to disrupt the Middle East.

In recent days, Mr. Sistani reportedly met with the leader of one political bloc, firebrand Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. His bloc, which rejects meddling by Iran, won the most seats in the election. The meeting fits Mr. Sistani’s long insistence that Iraqis act responsibly as a nation to avoid the “abyss of chaos and political obstruction.”

Unlike top Muslim clerics in neighboring Iran, Mr. Sistani believes Islam calls for clerics to largely stay away from ruling a country. He seeks a strong Iraqi identity rooted in democratic values that bind the country’s religious diversity. Yet in times of crisis, the still-divided Iraqis look to him for what he calls “caretaking” and “guidance.”

As in the past, he again walks a fine line between mosque and state. In many ways, though, he speaks for Iraqi youth. Their mass protests in 2019 altered the political landscape with demands for a government based on the common good, not the current power-sharing system that divvies up national resources by sects and ethnicity – with a high dose of corruption.

“The people and [Shiite religious authority Sistani] will reject any scenario of a Shia/Shia conflict, and any attempt will be defused,” Luay al-Khatteeb, Iraq’s former minister of energy, told Le Monde newspaper.

Delicate guidance now by Mr. Sistani fits his call for a corruption-free “civic state,” one based on political compromise rather than zero-sum competition. His calming effect comes as Iraq plans to host an international conference on interfaith dialogue scheduled for October.

The event, according to organizers, will emphasize equality in citizenship and guarantees of respect for all religions. After the near dismemberment of Iraq by the militant group Islamic State between 2014 and 2017, that is a message many Iraqis take to heart.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Love holds the control

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Larissa Snorek

Even when things get scary or difficult, we can yield to the power of God, divine Love, that brings confidence, wisdom, and safety.

Love holds the control

I imagine that most of us would probably prefer to avoid being thrown into a den of hungry lions against our will. Nor would we enter voluntarily into what looks like certain destruction!

This likely was also true in biblical times for Daniel, whose story describes a time under King Darius when being thrown into a den of lions was punishment for refusing to acknowledge the king as a god (see Daniel 6). Daniel continued to follow the First Commandment – to worship the one God he knew to be the only true God. And although the king had been tricked into meting out this punishment against his own personal wishes, Daniel’s profound trust in Love, God, protected him and the lions. The king celebrated with Daniel God’s saving power and the Love that held control and secured good for all.

Interestingly, Daniel’s prayers did not keep him from having to enter the lions’ den. But his understanding of God’s power gave him the spiritual realization that there was no real danger, even in the place that seemed most dangerous. He could go through this experience and be safe. Daniel brought such a sense of Love’s control over him, and all, that the ferocity of fear was neutralized. “Understanding the control which Love held over all, Daniel felt safe in the lions’ den,...” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 514).

Have you ever found yourself thinking that if only you’d prayed harder or studied more, then you wouldn’t have had to face some difficult thing? But scientific prayer is not employed to control circumstances or avoid facing hard things. On the contrary, it delivers us from fear, anxiety, and danger. It proves that no matter what hard things we have to face, Love holds the control and protects us. We understand this as we know God as Truth, Spirit, and Mind. This Mind causes its expression, each one of us, to know and feel divine presence and power in any circumstance.

Someone sent me a cartoon recently that said, “Relax! Nothing is under control.” But in order to really relax and stop running ourselves ragged trying to always keep things under control, we have to understand that control is held by a higher source – God. Understanding that divine Love is always governing allows us to relinquish a need to be in charge and to let go of attachment to a certain outcome. We can do this by yielding to Christ – the divine influence ever present in consciousness that enables us to see through the struggle to the pure gold and perfection of true, spiritual identity.

Yielding everything to Love, we find ourselves yearning more to experience dominion than to avoid challenges; more to gain the awareness of being the beautiful reflection of Soul, God, than to look a certain way; more to have a conscious, ongoing sense of unity with good, God, than to just fix a problem and go on our way; more to feel the spiritual power of our own innocence than to point out the faults of others.

Yielding to a Christlike approach of knowing Love’s power brings deliverance and healing. We discover happiness in trusting God as Soul rather than in trying to create perfection in our human experience.

When King Darius ran to the lions’ den the following morning, it was with the hope that Daniel’s trust in his God had delivered him. Explaining his protection, Daniel said, “My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions’ mouths, that they have not hurt me: forasmuch as before him innocency was found in me.”

The all-power of divine Love gives us a conscious sense of our freedom from apparent destructive forces. This same power operating for Daniel has not been displaced over time. When we gain confidence in our safety through an understanding of our unity with God as Mind, Love, and Spirit, we can face our own lion-like problems. The Christlike understanding of being facilitates protection from evil through the strength of innocence – true spirituality and godlikeness. Yielding to this Christly intuition brings us safely home to the confidence that good is operating – right where we feel a dread of something bad happening.

Knowing Mind’s government of all creation gives us equanimity and the confidence to find safety and security in the only place where true safety can be found – God. And we see that Love is all that can ever control us and all.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Aug. 15, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Unbreakable

A look ahead

Here’s a question for you: Who is Maryrose Wood? In tomorrow’s issue, Books Editor April Austin talks to the author, who writes for 8-to-12-year-olds. Ms. Woods says her stories are “animated by hope” – something that catches the eye of adults as well.