- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- More cash, fewer requirements: States scramble for teachers

- UK strikes: More than just a matter of money

- Independent unions are having a moment. But are they here to stay?

- ‘I put the students first’: A public school librarian on book bans

- Sowing dignity: Vertical Harvest grows produce – and community

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

For this innovator, an early start and an ambitious goal

If you’ve been to a science fair, then you’ve seen high schoolers standing beside trifold foam boards and 3D models. Most will go home, some to next-level competitions, a few to the forefront of solutioneering.

Robert Sansone belongs in category three. The 17-year-old high school senior from Florida is 16 iterations into his synchronous reluctance electric motor. Next focus: “minimizing torque ripple.”

Robert’s larger aim: to make the manufacturing of the motors that drive electric vehicles (EVs) greener. A recent story in Smithsonian magazine did a pretty good job summarizing his work, he says in a private exchange on LinkedIn, where he describes himself as “a life-long builder and designer.”

But why wade into such a competitive, big-player realm – one with complicated growing pains?

“I was watching a video on … EVs, where the issue with rare earth elements in their electric motors came up,” Robert writes. That bothered him. “We are moving away from the problems with fossil fuels, but are now moving into this new problem with rare earth elements.”

Robert knew motors existed that didn’t require such elements, the extraction of which carries environmental and human costs. Research taught him that such motors lack the performance needed for EVs. That’s where Robert’s work comes in.

For an assessment of his prospects I turned to Eric Evarts, a former Monitor auto and tech writer. Eric hails Robert’s breakthrough engineering (also recognized as such with a global award), adding caveats that surely hover around Robert already. Beating the performance of existing coil-wound motors is one thing. Matching the rare-earth permanent-magnet motors that EV makers use now? Hard to do (if even possible), or to scale.

Robert isn’t backing down. Not yet in college, he has some torque of his own – and plans for patents. “Seeing the day when EVs are fully sustainable due to the help of my novel motor design,” he tells Smithsonian, “would be a dream come true.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

More cash, fewer requirements: States scramble for teachers

At the heart of the struggle to retain and attract new teachers is restoring a sense of dignity to the profession. Beneath political finger-pointing, that goal is shared by a wide swath of Americans.

As students flood back into public schools for fall terms, one important item is missing from some classrooms: teachers. Nationwide, schools are thousands of teachers below their requirements.

It is not a general shortage so much as an intermittent one, say experts. Rural and poorer communities are hardest hit. Special education and other specific types of teachers are in the shortest supply.

States and localities are trying creative ways to attract the educators they need. Des Moines, Iowa, is offering a bonus of $50,000 in retirement funds to veteran teachers.

Alabama now recognizes out-of-state teacher licenses.

Florida enacted a law that allows veterans to teach with only two years of college.

Florida Rep. John Snyder was that bill’s author. A former U.S. Marine himself, he thinks veterans could be a natural source for future teachers because both are dedicated to public service.

“One of the overarching values in every branch of service is ... being part of something bigger than yourself – and that’s what education is,” Mr. Snyder says. “It’s tough, hard work, and it takes a level of commitment and dedication to see that through.”

More cash, fewer requirements: States scramble for teachers

Back in his days as a United States Marine, John Snyder studied for a college degree in between battlefield patrols. He retired with two years of college credits under his belt. He has no doubts that he was prepared at that point for another tough assignment: U.S. classroom teacher.

Mr. Snyder ended up going in a somewhat different direction and now works in education-related human relations. In addition, in 2020 he was elected to the Florida state legislature as representative for a district centered on the town of Stuart.

But all the threads of his background have now come together in a bold bid to help solve one of Florida’s big education problems: a teacher shortage dire enough that nearly 9,000 positions remain open in the state as the new school year grinds into gear. He wrote, and the legislature passed, a bill that allows veterans with two years of college but no degree to become licensed teachers.

As the law took effect last week, 233 military veterans applied for an expedited teaching certificate, which allows them five years to finish their bachelor’s degree.

“I’m blown away” by the response, says Mr. Snyder, adding that it confirmed his hunch that veterans could be an untapped resource for understaffed schools.

Florida’s not the only state that needs the help. As the crisper air, pumpkins, and back-to-school days of fall draw near, states across the U.S. sunbelt and beyond are struggling to fill an estimated 300,000 teacher and support staff vacancies nationwide, according to figures from the National Education Association, a teachers union.

The need has led to a proliferation of creative attempts to staff the classrooms. States are taking steps such as offering veteran teachers five-figure bonuses to postpone retirement, lowering the age for providing instruction, and reducing requirements for specific teaching slots.

The shortage is not so much general as nuanced, with particular geographical areas and types of teachers facing a crunch.

But addressing it has been made harder by the new scrutiny the teaching profession is facing in a polarized America riven by political fights about what should and shouldn’t be taught in public schools. Some experts say that a powerful recruitment tool for teachers might involve dialing back the culture wars and restoring a sense of dignity and respect for the teaching profession.

“America has paradoxical attitudes about teachers,” says Jane Rochmes, associate director of the Center for Education Research and Policy at Christopher Newport University, in Newport News, Virginia. “We’re entrusting teachers with our children, so that’s an incredible level of responsibility. At the same time, we have these derisive attitudes like, ‘Oh, I wouldn’t do it.’ ... We have swung from teachers being heroes to this questioning of things that teachers do.”

Scope of the problem

Nationwide, the depth and breadth of the teacher shortage is not unprecedented, and can partly be attributed to a tight labor market. The crisis isn’t uniform by region, neighborhood, or specialty.

Part of it may be caused by an influx of $190 billion in federal pandemic recovery funds aimed at catching kids up after several years of interrupted schooling. Forty percent of schools plan to expand staffing compared to pre-pandemic levels, according to a recent report by the Rand Corporation.

Experts say the problem is a big supply and demand mismatch in some regions and specialties. Rural and economically marginalized areas are experiencing recruiting and retention problems, especially in the special education and STEM – science, technology, engineering, and math – fields.

“At the national level, if you just look at the number of people getting teaching credentials, it still exceeds the number of slots,” says Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research in Arlington, Virginia. “So there’s not actually a number problem when we talk about teachers generically.”

What’s more, the nation saw “shockingly similar” school labor crunches in the 1990s and mid-2000s, Dr. Goldhaber says.

Yet it’s clear that some districts are struggling in new and profound ways to fully staff classrooms. According to the Rand study, three quarters of schools say they expect a teacher shortfall in the 2022-2023 school year, but not a large one. Seventeen percent of districts do anticipate a large shortage.

Nationally, the number of teachers graduating has dropped from 275,000 in 2010 to 200,000 in 2021, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Meanwhile, even before the pandemic, teachers were leaving their jobs at growing rates. Annual teacher turnover is now at 8%, up from 5.6% in the late 1980s, according to Learning Policy Institute figures.

Americans on the whole support their local schools and teachers, says University of Central Florida political scientist Aubrey Jewett.

But years of focus on student testing and ousting underperforming teachers from classrooms is now combining with an increase in politicization of curricula dealing with gender and race, leaving many teachers unsure of their mission and afraid for their jobs.

“Teacher turnover drives 90% of the teacher shortage,” says Henry Tran, a University of South Carolina associate professor of education. “With all the mandates and barriers, they cannot do what they believe is in the best interest of students.”

State and local incentives

All across the country school districts are hustling to try to fill their empty teaching slots.

Des Moines, Iowa, is offering a bonus of $50,000 in retirement funds to veteran teachers to stay another year. Over 50 educators have taken the district up on its offer.

Illinois earlier this year passed a package of bills aimed at easing its teacher shortage. The legislation, for example, reduced the age of being a substitute paraprofessional educator in grades K-8 from 19 to 18, effective January 2023, allowing students to move to the front of the classroom upon high school graduation.

Alabama now recognizes out-of-state teacher licenses.

And last month Arizona adopted a variation on Mr. Snyder’s idea in Florida by opening up teacher licenses to anyone enrolled in college, rather than requiring a degree in hand.

Florida itself is facing a difficult teacher staffing situation. The state has some of the lowest teacher salaries in the U.S. – but has also been hit hard by inflation, with rents up 30% in some locales. It also has some of the most heated curricula controversies in the nation.

Here in urban Duval County, the school district is short some 400 educators, causing the superintendent last week to warn students and parents that they will have to step up to make sure the school year is successful.

Amid the swaying palms and building thunderstorms Jacksonville, the throes of a national culture war can also be felt.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a potential presidential contender, has criticized teacher colleges for promoting “woke” activism.

The legislature has passed, and Governor DeSantis has signed, laws limiting the ability of teachers to discuss race and gender. Mr. DeSantis also injected himself into this week’s school board elections, endorsing dozens of candidates to what are supposedly nonpartisan positions.

At the same time, Governor DeSantis has signed teacher raises that have first-year teachers in Stuart, Florida, for example, seeing $48,000 starting salaries, up from $38,000 just a few years ago. Last week, Governor DeSantis vowed to expand Mr. Snyder’s recruitment bill to include retired law enforcement and first responders.

Nevertheless, the number of teachers graduating from Florida teaching institutions has nearly halved in the last five years. The staff shortages have become so acute in rural Lincoln County, for example, that the school superintendent has said he may have to drive a bus route.

“Maybe when you see the governor or other Republicans saying they are worried about the teacher shortage, it’s a bit of alligator tears here in Florida,” says Dr. Jewett, the UCF political scientist.

View from the flea market

High teacher turnover, reliance on substitutes, empty classes where an administrator rushes in to cover a class – all that is detrimental to student learning, says Dr. Rochmes of Christopher Newport University.

“These shortages keep districts from being their best in other ways,” she says.

Just ask Sam and Synthia.

The Duval County teenagers are walking through a Jacksonville flea market with a friend on Sunday afternoon, pushing a baby carriage with two mutt puppies they are hoping to sell.

Asked about a teacher shortage, Synthia says, “Ah, that’s been going on for years.”

She says it is what caused her to drop out of high school.

“The kids act up like crazy. They ran the teachers off. There was no point,” she says.

Sam says last year she had an environmental science class where subs sat without lesson plans for three semesters. A teacher was finally hired in the fourth quarter, and the class zoomed through the whole year’s curriculum in only eight weeks.

“We got through, but it was a little close,” says Sam.

A new Florida teacher encountered by the Monitor outside a Target in Yulee had a view of the educational system from the other side of the classroom.

She had just gotten a job as a teacher, having moved to Nassau County with her husband, who has recently retired from the military. (She asked not to be named out of a concern that any public comments could affect her work, pension, and job prospects.)

New to the state, she has begun to learn evolving rules as to what teachers can and can’t discuss with students with regard to sensitive or controversial topics.

“The protocol is basically to say, ‘I’m here, I support you,’ but not to appear to be guiding anyone,” she says.

Her stress level has been further increased by controversy over the contents of the school library.

“We have to go through our library [to weed out banned books] and, to be honest, I haven’t had time to do that yet,” she says.

Fundamental reforms

There is some evidence that the difficult questions swirling around the roles of America’s teachers are stirring attempts at more fundamental reforms.

Savannah, Georgia, teacher Cherie Goldman just spent a sabbatical year crisscrossing Georgia to talk to teachers for a just-released Teacher Burnout Taskforce report. The report found that pay is a problem, but so is the sheer amount of red tape that steals time from classroom instruction.

Schools and the teachers and students that mill through them are “just so foundational to the intricacies and relationships that bind and build our communities, and our society, for the better,” says Ms. Goldman, an English as a second language teacher who was voted Georgia’s 2022 Teacher of the Year.

The voices of negativity surrounding education are exhausting, Ms. Goldman says. Teachers pour their hearts and souls into their jobs and they found it disheartening when their sheer effort isn’t appreciated.

“There is so much depth to education. It’s so much richer than it has been diminished to be for a catchy headline, a catchy tweet,” she adds. “People have lost sight of the tremendous things that are happening in school buildings every single day on behalf of students, families and communities.”

Mr. Snyder in Florida agrees. His bill to bring veterans into teaching has received some criticism nationally. But he sees it as an effort to recruit teachers who have already proven themselves devoted to public service.

“One of the overarching values in every branch of [military] service is ... being part of something bigger than yourself – and that’s what education is. It’s tough, hard work, and it takes a level of commitment and dedication to see that through.”

UK strikes: More than just a matter of money

A highly unusual wave of strikes in Britain suggests that fears of a recession and resentment at lagging pay rises are sharpened by a sense of social injustice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

For nearly 50 years, British workers have been relatively quiescent. But this summer they have launched a series of rolling strikes that would put their French counterparts to shame.

Railway workers, doctors, postal workers, and barristers are just some of the groups going on strike for higher wages – and disrupting wide sectors of the economy in pursuit of their goals.

The strikes have been especially drawn out because the government has been adamant in limiting public sector salaries. But behind this summer’s explosion of labor unrest is “10 years’ worth of inflation that hasn’t been matched by wages,” says employment lawyer James Conley.

Widespread resentment at this state of affairs has been sharpened by a sense of injustice; wage inequality has been widening in the United Kingdom this year faster than anywhere else in Europe besides Estonia.

A fear of recession, which threatens to bring layoffs and pay cuts, has fed a sense that Britain is at a breaking point where something has to be done. This summer of discontent, says labor activist Tatiana Garavito, has exposed “a growing dissatisfaction in the U.K. with how things are working.”

UK strikes: More than just a matter of money

Unlike their neighbors in France, Britons aren’t exactly famed for going on strike; “keep calm and carry on” and “stiff upper lips” are more their style.

But a current wave of strikes in Britain, the likes of which have not been seen for nearly half a century, is challenging that image.

The highest inflation rates for 40 years, spiraling energy prices, and the government’s refusal to meet employees’ demands for pay rises to match those increases have created “a perfect storm” after years of smoldering discontent, says teacher Rob Poole, who has had to put up with below-inflation pay rises for more than a decade.

“We’ve had 10 years’ worth of inflation that hasn’t been matched by wages,” adds employment lawyer James Conley. “Staff are so much worse off now that those areas of the workforce that are heavily unionized” such as the public sector “are looking to do something.”

The result has been a “summer of discontent,” with rolling strikes disrupting broad areas of the economy. Rail workers brought trains to a halt nationwide again on Saturday, and dock workers at Britain’s largest port, Felixstowe, launched an eight-day strike over the weekend in support of wage demands.

On Monday, barristers in England and Wales announced they would strike indefinitely from Sept. 5 to back demands for a 25% salary increase.

“When they go on strike, you know there’s a more systemic issue with pay and inflation that crosses professions,” says Mr. Conley.

A sense of injustice

Behind the pay demands lie a decade of cutbacks in public services and social welfare schemes, growing resentment at corporate and political hypocrisy, and a widening gap between rich and poor people. Inequality has risen faster in the United Kingdom than anywhere else in Europe except Estonia, since energy prices began to rise this year, according to the International Monetary Fund.

A sense of injustice underpins the newfound zest for strikes, bringing together ordinary people from myriad jobs and professions, says British-Colombian labor activist Tatiana Garavito. She sees this summer as a watershed moment exposing “a growing dissatisfaction in the U.K. with how things are working.”

After 50 years of relative quiescence, British workers are turning to the kind of industrial action more common in Latin America, she says, where “the material realities of people … are urgent.”

Doctors, nurses, teachers, postal workers, airport baggage handlers, bus drivers, container port staff, and barristers are among a dozen professions going on strike. But it is Britain’s railway workers, backed by large trade unions, and grinding the rail network to a halt, that have lit the spark that has inspired others.

The voice of the summer’s discontent has belonged to Mick Lynch, the unflappable leader of the transport workers’ trade union turned folk hero. His no-nonsense rebuttal of critical journalists and politicians has won wide public admiration, set social media platform TikTok alight, and rekindled public sympathy for trade unions at a time when just 23% of U.K. employees are union members, a record low.

Mr. Lynch’s campaigning has been a boon for the union movement.

“People have, for a long time, questioned why they are paying fees to unions,” says Mr. Conley. “It’s a little bit of posturing from unions to assert their dominance, make themselves appear more boisterous and more effective. They’ve clearly struck a nerve.”

Mr. Lynch’s booming rallying calls against “a government of billionaires” have also appealed to disgruntled workers in other professions less accustomed to striking, such as doctors and nurses. Worn down by the pandemic, they have been offered just a 1% pay rise after two years at the negotiating table.

In that time, “glaring differences between the rhetoric of politicians clapping for key workers during the pandemic and the way they have been treated in the workplace” have become apparent, says Mr. Poole, co-founder of a virtual map of picket line locations.

“Rank hypocrisy”

For Tim Colledge, a physiotherapist working in the state-run National Health Service, “rank hypocrisy is politicizing many [of us] who aren’t usually politically minded.”

Though Britain is no stranger to charges of political hypocrisy, recent instances of rule breaking by officials, including outgoing Prime Minister Boris Johnson, have added to a sense of a ruling class that is dodging its responsibilities. And demands for more corporate responsibility have also fueled discontent.

British shipping company P&O Ferries recently fired nearly 800 employees and immediately replaced them with foreign workers on the minimum wage. Oil giant BP recorded its biggest profit in 14 years, while energy firms say they are planning to charge consumers this autumn more than twice as much as they paid a year earlier. In August, workers at Amazon’s biggest U.K. warehouse walked out, rejecting a 35p (42 cents) per hour pay rise.

The summer of discontent reverses a three-decade decline in industrial action. Anti-trade union laws passed between 1980 and 1993 mean that the U.K. has the most restrictive anti-union laws in Europe, which “make actually going on strike difficult,” says Mr. Poole.

But a growing “yearning for connections” with climate change and racial and gender-equality movements has spurred more union activism, suggests Ms. Garavito.

Multifaceted solidarity has been a hallmark of past labor movements in Britain, notably before World War I, when major labor strikes coincided with the women’s suffrage movement.

The coal miners’ strike of the 1980s, which bitterly divided the country, gained many “fervent supporters from many walks of life,” recalls historian Sheila Rowbotham, while Black and South Asian women often joined forces to protest against racial discrimination and gender inequality, as well as workplace conditions.

This summer, though, the overriding factors driving the strikers appear to be economic. “It comes down to a genuine fear of recession,” argues Mr. Conley. “You’ll get lots of people made redundant, or having to take a pay cut. There is a general consensus that this is a breaking point, and something has to be done.”

The Explainer

Independent unions are having a moment. But are they here to stay?

A new wave of labor organizers is bucking the old guard, raising questions about the future of power in the workplace, and the cooperation it may take for workers to stand their ground.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When workers at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island voted to unionize in April, it kicked off an exciting summer for pro-union activists. New unions are popping up in stores of big national brands from Apple, to Starbucks, to Trader Joe’s, and now even Lululemon.

The Amazon Labor Union was new – founded in 2019 – and independent. It had no formal ties to well-established organizers like Teamsters or the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union that had spent years and millions of dollars trying to organize Amazon workers.

There have been bursts of grassroots labor movements before, but they haven’t reversed the steady decline in unions’ membership and power in the United States. The future of labor organizing may require cooperation between established unions and independent ones.

“With this newfound energy and creativity and interest and support, [grassroots unions] stand a chance of really getting things going,” says Jon Hiatt, who served as the AFL-CIO’s chief legal counsel and still works in labor law. “But I think there’s a real chance it’s going to die out if organized labor doesn’t bring the institutional support that is going to be necessary to keep it going.”

Independent unions are having a moment. But are they here to stay?

When workers at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island voted to unionize in April, it kicked off an exciting summer for pro-union activists. New unions are popping up in stores of big national brands from Apple, to Starbucks, to Trader Joe’s, and now even Lululemon.

But the win at that Amazon warehouse was the most eye-catching, and the least expected. The union, which called itself Amazon Labor Union (ALU), was new – founded in 2019 – and independent. It had no formal ties to well-established unions like the Teamsters or the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union that had spent years and millions of dollars trying to organize Amazon workers.

“No one thought they had a chance of winning,” says John Logan, a professor of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State University. “No one had ever heard of the Amazon Labor Union.”

Now, however, the ALU is the hottest news in the labor movement. Its success is inspiring others to follow its footsteps and take the same, independent route. But sustaining that success may require cooperation with the organizations they eschew.

What is an independent union?

An independent union is a union that has no official affiliation with larger organizations like the United Auto Workers or the Teamsters. Most unions fit into a huge hierarchy. Workers at a grocery store might belong to a local branch of the United Food and Commercial Workers, which in turn is part of the AFL-CIO, one of two federations that, together, represent nearly all of America’s union workers.

Independent unions don’t fit into those hierarchies. They’re on their own. They tend to represent workers in one specific industry or even a single workplace, but apart from being unaffiliated, they function just like any other union.

What are the drawbacks to independent unions?

The main downside is that independent unions typically don’t have the same resources or clout as more established unions. Patricia Campos-Medina, executive director of The Worker Institute at Cornell University’s labor relations school, says large, affiliated unions “have organized legal departments, well-organized communications departments, relationships with elected officials to drive policy,” and, of course, deep pockets.

By contrast, ALU crowdsourced about $120,000 and got pro bono help from labor lawyers and veteran union organizers. That’s not much to go on compared with the coffers of long-standing unions, or the roughly $4.3 million that Amazon reported spending on anti-union efforts in 2021.

On the other hand, independent outfits have an advantage in credibility. Independent organizers bring intimate knowledge of their workplace that lets them craft tailored ideas for improving it. When big unions want to unionize a workplace, they often show up as outsiders. Dr. Logan says companies often tell their employees that a union is an external force that “doesn’t really either understand or even necessarily care about the things that are your concerns with the workplace.”

Chris Smalls, one of ALU’s leaders, has said that that kind of unfamiliarity was one reason a long-standing union’s recent effort to organize an Alabama Amazon warehouse has failed so far.

ALU’s credibility has won over another Amazon facility, near Albany, New York, where would-be union members have chosen to organize with the fledgling ALU.

Trader Joe’s employees in Hadley, Massachusetts, who just formed an independent union of their own, voiced the same eagerness for autonomy, saying they didn’t want just another “boilerplate” contract. On Aug. 12, a Minnesota store voted to follow them into the union, 55-5.

What’s next and what does this mean for the overall labor movement?

There have been bursts of grassroots organizing before, but they haven’t reversed the steady decline in unions’ membership and power in the United States.

“With this newfound energy and creativity and interest and support, [grassroots unions] stand a chance of really getting things going,” says Jon Hiatt, who served as the AFL-CIO’s chief legal counsel and still works in labor law. “But I think there’s a real chance it’s going to die out if organized labor doesn’t bring the institutional support that is going to be necessary to keep it going.”

Evolution might look like what’s happening with Starbucks. Workers at over 200 of the coffee shops have been unionizing with the same kind of grassroots passion shown by ALU, but their union, Starbucks Workers United, has official backing from Workers United, which itself is linked to the huge Service Employees International Union.

The future of labor movements may very well depend on similar cooperation. Grassroots organizers are “forcing international unions to learn to be more nimble and actually not make all the decisions at the top,” says Dr. Campos-Medina. “[Established unions] need to give local leaders a bit more room to be creative.”

Q&A

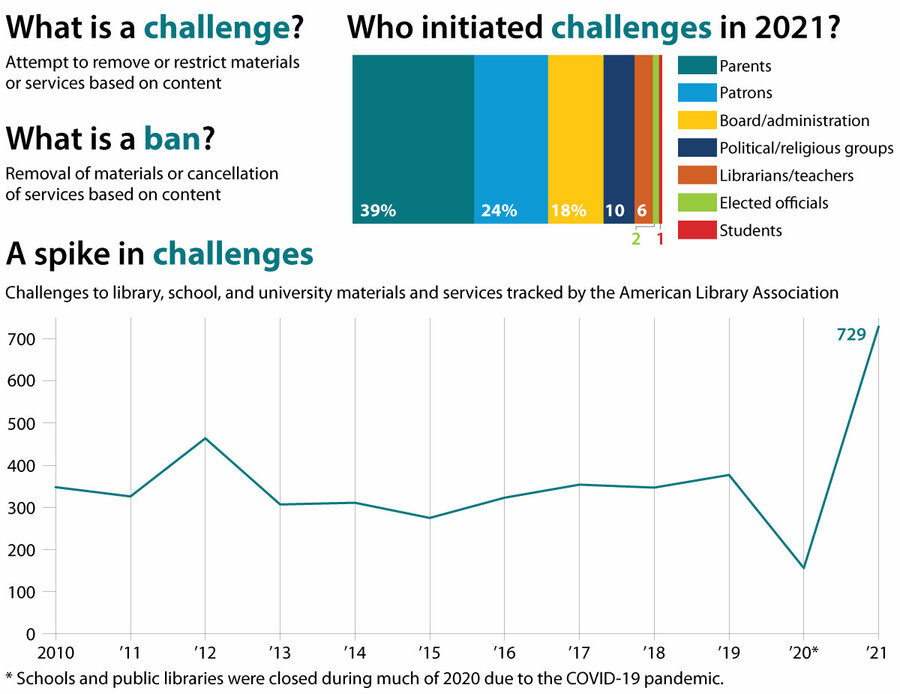

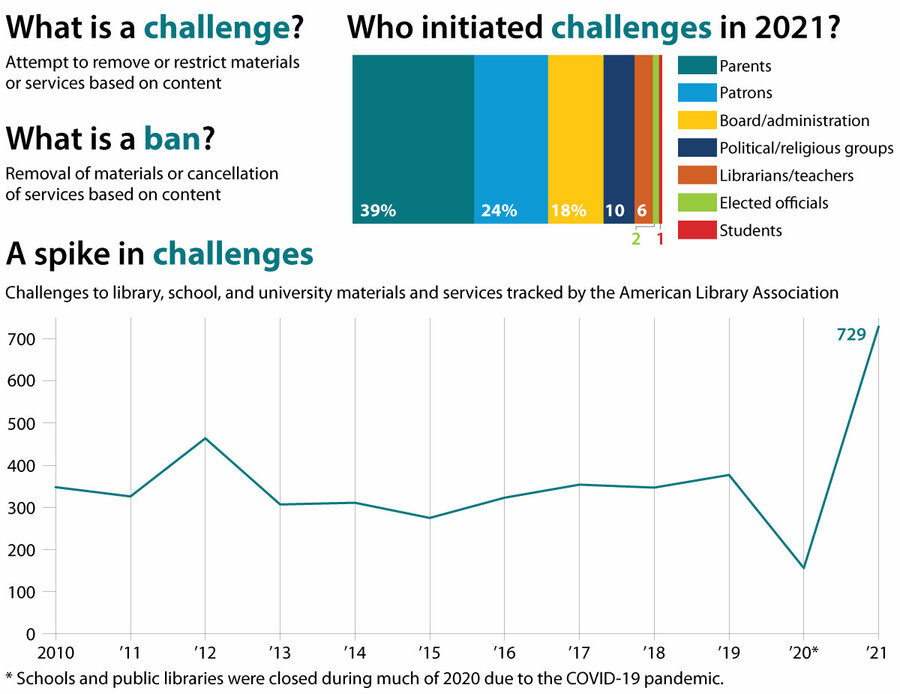

‘I put the students first’: A public school librarian on book bans

As some parents push book bans, scrutiny extends to school staff. Yet school librarians like Martha Hickson defend their responsibility to students.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Calls to ban books – from classrooms and library stacks – are on the rise, but they aren’t new. Usually, direct dialogue with parents resolves book concerns, says librarian Martha Hickson, in her 18th year at North Hunterdon High School in Annandale, New Jersey.

“I put the students first and foremost, but of course parents are a part of the equation,” she says. “My obligation is to first listen, understand what the concern is, and then to help the parent understand how and why the book is in the library, and then to remind the parent that library materials are there for voluntary inquiry.”

“Nobody must read a library book,” she continues. “If the book in question is not compatible with the parent or student’s reading preferences, let’s choose another.”

Asked what gets left out of news coverage on the topic, she answers, “The parents who support the right to read and the voices of librarians. What’s been happening is, because the language and the tactics of the book banners are so outrageous, that grabs eyes and attention. It’s practically clickbait.”

“In my community,” she adds, “my experience is those voices are very few, but very loud.”

‘I put the students first’: A public school librarian on book bans

Calls to ban books – from classrooms and library stacks – are on the rise, but they aren’t new. Direct dialogue with parents often resolves book concerns, though they’ve been rare, says librarian Martha Hickson, in her 18th year at North Hunterdon High School in Annandale, New Jersey.

What is new: having to defend not just titles for teens, but herself.

Backlash began at a school board meeting last September during Banned Books Week. A local parent claimed the school library’s inclusion of certain books with sexual references was an effort to “groom” students as potential victims of pedophilia. Next, says Ms. Hickson, came hate mail – an example of the scrutiny faced by school staff countrywide in this culture war.

“I have never seen anything like this in my lifetime, with the exception of maybe in history books,” says the librarian, who helped defend five LGBTQ-themed books from removal. “I’m thinking of the Nazi era, or perhaps the McCarthy era with the Red Scare.”

The Monitor spoke with Ms. Hickson, who received a 2020 American Association of School Librarians’ Intellectual Freedom Award, about her responsibility to young readers. The conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

How do you define your duty to students?

My duty to students is essentially to enable them to go out into the world to be effective and discerning users of information, and lifelong learners.

How do you define your duty to parents?

I put the students first and foremost, but of course parents are a part of the equation. My duty to parents is to work with them within the guidelines established by the school system and the board. There are policies and rules in place to help me and the parents work together when there is a concern about a book. That process should begin with a conversation with the librarian and/or the principal. In that conversation, my obligation is to first listen, understand what the concern is, and then to help the parent understand how and why the book is in the library, and then to remind the parent that library materials are there for voluntary inquiry.

Nobody must read a library book. If the book in question is not compatible with the parent or student’s reading preferences, let’s choose another.

Calls to ban award-winning books like “Gender Queer: A Memoir” – featuring LGBTQ protagonists as well as sexually explicit content – have included allegations of pornography. How do you reconcile perceptions of harm with your embrace of intellectual freedom?

Perceptions of harm have to also come in contact with reality ... and legal precedent. There is the Miller rule regarding obscenity – and this is one of the things that is getting overlooked repeatedly. This is the Supreme Court guideline, and the major element there is viewing the work as a whole. Is the work as a whole patently vulgar?

In the example of “Gender Queer,” time and time again, including in my own district, the decision has been that no, it is not. In fact, a book such as this contains value for helping individuals who are questioning gender identity or sexuality understand that there are others in the world like them.

Have you personally seen the value of the types of books now being challenged in an individual student’s life?

Absolutely. Every day. One of the books that was challenged in my library is a book called “This Book Is Gay” by Juno Dawson. It’s essentially a handbook for kids who are either questioning or just understanding their sexual identity. It covers all the things that a young person might have questions about in that situation – things about dating, coming out, bullying, religion, and, yes, sex.

The cover of this book is bright, broad rainbow stripes ... [and] says “This Book Is Gay.” Can you imagine being 14 years old and having the backbone and the courage to take that book off the shelf, walk through the library with it, hand it to me – a 62-year-old woman, whom you barely know, perhaps – and check it out? That’s an act of courage and trust. I respect so greatly – and value so greatly – that a teenager trusts me enough to hand me that book and know that they’re safe in my hands. That kind of transaction happens every day in our library.

I have received a number of emails from former students – kids who weren’t out at the time that they were in high school – who’ve thanked me for having a library that was a safe space for them, where they saw themselves represented on the shelves.

American Library Association

Is there anything in the coverage of book bans – or school librarians more generally – that gets left out of the news?

I think one of the things that gets left out of the news a lot of times is the voice of the other side ... the parents who support the right to read and the voices of librarians. What’s been happening is, because the language and the tactics of the book banners are so outrageous, that grabs eyes and attention. It’s practically clickbait, so a lot of the coverage gives a lot of space to those voices. ... At least in my community, my experience is those voices are very few, but very loud.

Many librarians, rightly so, are incredibly fearful for their personal safety, for their family’s safety, for their job security. They don’t feel at liberty to speak out.

What, if anything, gives you hope?

The pattern of history shows that these eruptions of censorship are cyclical. I am hopeful that the library community in particular, and the society at large, are learning valuable lessons from this experience that we can apply the next time the cycle happens.

In sort of a broader, happier sense, one of the things that gives me hope is the kids. We didn’t get into this, but among the community that came out to support the right to read were a huge number of students who were the most passionate, persuasive, eloquent public speakers. To see the kids rise up and say, “No, these are my books, and you can’t take them away, because they’re valuable to me,” was beautiful.

American Library Association

Difference-maker

Sowing dignity: Vertical Harvest grows produce – and community

People with disabilities often have a hard time finding meaningful employment. But a Wyoming greenhouse provides just that, planting seeds of dignity to cultivate robust lives and professional success.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Jodi Hausen Contributor

Vertical Harvest, in Jackson, Wyoming, produces about 100,000 pounds of lettuce, microgreens, and tomatoes annually. That’s a big deal in this ski town where the growing season is four months at best. Equally important, about 40% of the greenhouse’s employees are people with disabilities.

The unemployment rate for people with disabilities in Wyoming is 9.7%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 five-year estimate. That’s lower than the 11.4% national average – which is about twice that of people without a disability.

Founded in 2016, Vertical Harvest was built to address this disparity, and its success is in part due to Caroline Croft Estay’s work in creating the Grow Well model of employment. Designed to foster employees’ professional development, personal discovery, and community impact, Grow Well uses customized employment plans that take into account individuals’ strengths, attributes, and aspirations.

Anna Olson, president of the Jackson Hole Chamber of Commerce, says Grow Well’s unique model showcases the potential for people of all abilities working together.

“Caroline ... really understands and believes [people with disabilities] have equal rights and equal ability to contribute in our community,” she says. “And we need to open our minds to that.”

Sowing dignity: Vertical Harvest grows produce – and community

To say Caroline Croft Estay is as bright and sparkly as the hot pink glitter polish she wears on her fingernails would be, at the very least, apt. The co-founder of Vertical Harvest in Jackson, Wyoming, sits in the break room of the greenhouse, where employees come and go, many stopping by to say hi, to give her updates, or simply to smother her in hugs.

“She’s just an inspiration,” says employee Destiny Kennington. “She’s smart, bubbly, kind, and really understanding of everyone and everyone’s personal needs.”

Ms. Croft Estay is also chief potential officer for the three-story farm that produces about 100,000 pounds of lettuce, microgreens, and tomatoes annually. That’s a big deal for this ski town, where the growing season is four months at best. Equally important, about 40% of the greenhouse’s employees are people with disabilities.

Disabled people often have a hard time finding meaningful work, and the purpose and community that come with it. Vertical Harvest provides that, with a unique employment model that recognizes certain traits as talent, and nurtures personal and professional growth by treating every individual with dignity.

The Grow Well model

The unemployment rate for people with disabilities in Wyoming is 9.7%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 five-year estimate. That’s lower than the 11.4% national average – which is about twice that of people without a disability.

Founded in 2016, Vertical Harvest was built to address this disparity, and its success is in part due to Ms. Croft Estay’s work in creating the Grow Well model of employment. Designed to foster employees’ professional development, personal discovery, and community impact, Grow Well uses customized employment plans that take into account individuals’ strengths, attributes, and aspirations.

Getting to know Johnny Fifles, who has autism, Ms. Croft Estay recognized his extraordinary attention to detail and ability to hyperfocus. As such, Mr. Fifles excels at seeding microgreens on cellulose mats in a single layer. “No more, no less,” he says.

This framework conveys dignity to every job. Workers thrive and get promoted.

“If I get a promotion, it’s telling me that I’m doing a good job and maybe in a few years, I’ll get another promotion or raise,” says Sean Stone, an original Vertical Harvest employee who’s risen to become a senior facilities associate. Previous jobs didn’t give him that same opportunity – or reason to hope. “If I’d be a dishwasher for four years, I may never get promoted,” he says.

“Mama bear”

Brought up in the South, Ms. Croft Estay studied psychology and education at the University of South Carolina, then fell in love with the Mountain West after a summer working in Yellowstone National Park. Losing her mother as a young child, and becoming a mother in her early 20s, likely cultivated her “mama bear” instincts, she says. “I’ve always looked out for the underdog. I think it’s just making sure that my cubs, everybody’s good.”

Ms. Croft Estay became a state-certified Medicaid provider, working one-on-one with disabled people. It was so difficult finding them employment that she considered creating a compost pickup program to provide them jobs. Local connections led her to Nona Yehia, an architect who was already working on an indoor farming project. The women teamed up to co-found Vertical Harvest, which is now expanding.

The company recently broke ground on a 70,000-square-foot building in Westbrook, Maine, that is expected to grow 2 million pounds of produce annually. And there are plans for additional facilities across the country, each one guided by the Grow Well model to cultivate dignity in underserved communities through inclusion and accessibility.

But getting here wasn’t easy. The company’s first year was challenging, says Ms. Croft Estay, who experienced her own growth then, too. She realized she’d been overprotecting some of her employees, sometimes speaking for or limiting them. “As a case manager here, I think I’m so progressive. I’m such an advocate,” she says. “It took this greenhouse to expose where I still had judgments or barriers or reservations.”

As if on cue, Ms. Croft Estay notices 40-year-old Mycah Miller, who has Down syndrome, and tells her to avoid picking at a small wound on her shoulder. “I’m watching you. I’m mothering you,” says Ms. Croft Estay, offering to put a bandage on it.

Business is social

Grow Well goes beyond the workplace. Vertical Harvest fields a team in Jackson’s kickball league where 95% of employees participate. They also sell produce at farmers markets; lobby and march together to advocate for diversity, inclusion, and social justice; and have monthly “happiest hours” – an evening out on the town. People with disabilities are often lonely, Ms. Croft Estay notes, and these activities bring dignity to their personal lives.

Jessie Phillips-Grannis coordinates employment for people with disabilities for Community Entry Services in Jackson. She’s had several clients work at Vertical Harvest and calls the company’s approach effective and life-changing. One of her clients just started there.

“I am already seeing it being more empowering to him than other places he’s worked,” she says. “He feels he’s part of something that matters and that’s important and huge and something he isn’t going to find if he was working someplace else.”

Anna Olson, president of the Jackson Hole Chamber of Commerce, says Grow Well’s unique model showcases the potential for people of all abilities working together.

“Caroline ... really understands and believes [people with disabilities] have equal rights and equal ability to contribute in our community,” she says. “And we need to open our minds to that.”

“They are driving the future of what, hopefully, employing people with disabilities looks like,” says Ms. Phillips-Grannis.

Often, institutional structures and rules “remove the human side of the human,” Ms. Croft Estay says. But in the day-to-day grind of producing thousands of pounds of food, dignity supplants stereotypes.

“Because we are sitting here sweating, working side by side getting product out the door ... all those barriers and all those stigmas, they go away. ... We don’t do helplessness. ... We’re a family. We’re a system.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Bytes and bravery over bullets

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

So far in 2022 the world has witnessed three major displays of military might. Russia invaded Ukraine in February. In August, China encircled Taiwan for four days of massive “military exercises.” Less noticed, Iran has announced it has “hundreds of thousands of rockets” arrayed against Israel.

As scary as all this aggression is, the three recipients of that violence – Ukraine, Taiwan, and Israel – have found the mental and moral qualities to respond.

By the pluck of his leadership to defend Ukraine’s freedom, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has rallied both his country and much of the democratic world by asking this sort of inspirational challenge: “When hatred knocks on your door, will you be ready?”

As part of its defense against China, Taiwan is championing qualities of a democracy, such as freedom of thought and rule of law that nurture individual innovation. The island is home to the world’s largest contact chipmaker.

In Israel, a democratic spirit of innovation has helped erode Iran’s menace. The country is a world power in high-tech entrepreneurship. Many of Israel’s Arab neighbors want to join that freedom-fueled innovation, cornering Iran’s regional ambitions by the new political alliances.

Bytes and bravery over bullets

So far in 2022 the world has witnessed three major displays of military might. Russia, of course, invaded Ukraine in February with nearly 200,000 troops and indiscriminate rocket attacks. In August, China responded to U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan by encircling the island nation for four days of massive “military exercises” that included, for the first time, firing missiles over the island. Less noticed, Iran has announced it has “hundreds of thousands of rockets” arrayed against Israel from Syria to Lebanon to Gaza.

As scary as all this aggression is, the three recipients of that violence – Ukraine, Taiwan, and Israel – have found the mental and moral qualities to respond.

By the pluck of his leadership to defend Ukraine’s freedom, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has been voted the world’s most influential person by Time magazine’s readers. That began with his decision to stay in a besieged Kyiv, walking about with brave certainty of Ukraine’s sovereign future. Most likely he will be named Time’s Person of the Year. Mr. Zelenskyy has rallied both his country and much of the democratic world by asking this sort of inspirational challenge: “When hatred knocks on your door, will you be ready?”

As part of its defense against China, Taiwan is championing essential qualities of a democracy, such as freedom of thought and rule of law that nurture individual innovation. The island is home to the world’s largest contract chipmaker, making it an essential source for the high-tech industry – including in China. Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, said Monday that democracies like hers can ensure a reliable supply of semiconductors to each other, or what she called “democracy chips.”

China is making “the mistake of thinking that simple military might makes a nation a great power,” former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage told Radio Free Asia this week.

In Israel, a similar democratic spirit of innovation has helped erode Iran’s menace. The country is a world power in high-tech entrepreneurship despite its small population. It is home to 10% of the world’s “unicorns,” or companies worth $1 billion and not yet publicly traded. Last year, $25 billion was invested in Israeli high-tech startups.

Many of Israel’s Arab neighbors want to join that freedom-fueled innovation. They signed the 2020 Abraham Accords to recognize the Jewish state and now eagerly welcome Israeli investments. “I liken it to the ‘Sand Curtain’ just dropped, much like the Iron Curtain,” OurCrowd founder and venture capitalist Jonathan Medved told The Media Line news site.

Israel’s tech dynamism, built on the creativity that open societies nurture, has begun to corner Iran’s regional ambitions by the new political alliances. Like China and Russia, Iran may be discovering that the bytes and bravery of democracies are a strong match for bullets and ballistic missiles.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The good news

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Caryl Emra Farkas

Even in the face of bad news, the ever-present light of Christ is here to comfort and transform.

The good news

In the decades leading up to Jesus’ birth, just as during his lifetime, momentous events were unfolding. In the Roman Republic Pompey the Great besieged Jerusalem, killing 12,000 Jews; civil war broke out in Rome. Julius Caesar emerged the victor in the civil war and was appointed dictator, but shortly after he was assassinated. Eventually Augustus became head of the new Roman Empire.

While there was no news media then as we know it today, Jesus and his followers were likely aware of important events taking place during their time. But when we search the Gospels, what references to world events and politics do we find?

Jesus’ teachings center on our relation to God and on the fact that Christ, God’s spiritual idea, is always with us, always here to help and heal. One place in which Jesus did address news of the world, though, is this statement to his disciples: “Ye shall hear of wars and rumours of wars: see that ye be not troubled” (Matthew 24:6).

Jesus wasn’t telling his followers to be unconcerned about what was going on around them. He wanted them to see that God is bigger and more powerful than any threat they could hear of. He knew that the only way to “be not troubled” is to gain a truer idea of life as spiritual and of each of us as children of God rather than mortal men and women.

Through all he said and did, Jesus proved that sin, disease, and death could not overcome divine Life, Truth, and Love. His manifestation of Christ, including his knowledge and conviction of God’s invariable presence and the supremacy of divine good, consistently removed not just fear but all evidence of any kind of trouble.

In his instructions on how to pray, Jesus taught his disciples how to realize God’s presence and power. First, he told them, “Enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret” (Matthew 6:6). And then he took them through an exposition of divine reality that Mary Baker Eddy referred to as “that prayer which covers all human needs” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 16). The entire Lord’s Prayer is about rising above a merely material sense of life and trusting in God’s always-present law of Love.

The carnal mind reports life as no more than the serial ups and downs of material conditions, which ultimately end in death. Such thinking would leave us with a vision of existence utterly without God. But in her spiritual interpretation of the final line of the Lord’s Prayer, “For Thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever,” Mrs. Eddy presents the Christianly scientific view of life: “For God is infinite, all-power, all Life, Truth, Love, over all, and All” (Science and Health, p. 17). This is the good news of the Gospels: that God’s kingdom, power, and glory are always true, always with us, always here to comfort us and transform our experience.

On the basis of their grasp of this good news, the apostles navigated times of divisiveness, violence, and political upheavals, leaving behind not complaints but an inspiring chronicle of healings, life-changing spiritual visions, rescues, and journeys full of “signs and wonders.” So, we too can bring to light God’s ever-present good and find our own and others’ expression of that divine goodness even amidst bad news.

This is not ignoring problems or pretending they don’t exist, but refuting them with the Mind of Christ, sure of the all-power of divine Love. In this way, we not only bring calm but ultimately aid in the reversal or destruction of evils.

Mrs. Eddy wrote in Science and Health: “This material world is even now becoming the arena for conflicting forces. On one side there will be discord and dismay; on the other side there will be Science and peace. The breaking up of material beliefs may seem to be famine and pestilence, want and woe, sin, sickness, and death, which assume new phases until their nothingness appears” (p. 96).

When confronted with disturbing reports, we need not wonder, “Why are things so bad?” We can remember that any report that leaves out God, good, is incomplete. No matter what appears to be going on, we can find the imprints of God’s good news, and trust that it will be manifested more fully as we steadfastly plant our hope, faith, and understanding in God’s goodness.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Aug. 22, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

She changed the course of history

A look ahead

Thanks again for starting your week with us. Tomorrow we’ll have a report from Martin Kuz on how Ukrainians’ remembering and honoring of loved ones killed in war reveals an essential humanity that defies the barbarism of the conflict.