- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Election deniers on ballot: What does this mean for democracy?

- Education Secretary Miguel Cardona on debt relief and teacher shortages

- In Jackson, a crisis of water – and a broken social contract

- No Paris? No problem! Russian tourists holiday in the homeland.

- At Fly Compton, the sky’s not a limit. Neither is race.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Monitor launches a new way to look at news

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Talk to anyone in journalism. “News avoidance” is a thing. People simply can’t cope with a daily dose of anger, failure, fear, and frustration. The Monitor was created to antidote this narrow view of news. Starting today, we’re going to make that even plainer.

Some of you will remember our Respect Project or Finding Resilience. By focusing on the values behind the news, we gave you a deeper view of the news and showed how it can highlight solutions that unite rather than divide. We’re going to do much more of this going forward. We’re going to clearly identify the values driving the news – whether it’s respect, compassion, responsibility, freedom, or so on. You can see how we’re starting this by clicking here.

This approach tells you why the story really matters – it gets to the heart of what people and societies are really wrestling with. But it also better explains why the story matters to you – showing how news from Mozambique to Minnesota has a universal relevance.

At first, these changes might not be apparent in places that you, as a subscriber, will recognize. In September, we’ll be focusing mostly on changes to the layout of the stories on our website. But we’ll make these changes more apparent in the Daily in the coming months.

The question we ask ourselves every day is: What more can we do to support the mission of our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, to do constructive, healing journalism that blesses all? We see this as something no one else in journalism is doing – and key to re-imagining the good that journalism can do in difficult times.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Election deniers on ballot: What does this mean for democracy?

Some Republicans who deny the validity of the 2020 vote are running for office in 2022. If they win, what happens to trust in U.S. elections?

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Across America, Republicans who question the legitimacy of the last presidential election are on the ballot for the 2022 midterms. At least 195 GOP Senate, House, governor, attorney general, or secretary of state nominees have echoed former President Donald Trump’s false charge that the presidential election was stolen, FiveThirtyEight estimated this week.

Yet multiple reviews have shown the election to be fair and the results accurate. Multiple officials of both parties, including Mr. Trump’s former Attorney General William Barr, have said they saw no evidence of widespread fraud.

Whether election deniers in key positions could have flipped 2020 for Mr. Trump is an open question. Not every candidate who criticizes the last presidential vote is embracing disinformation or false claims. For many, it may be a way of expressing anger at the 2020 outcome or continued support for Mr. Trump.

The U.S. election system is very decentralized, even for national elections. Many different levels of government have a hand in administering the vote. Key officials who oversee elections are themselves elected, meaning they can become partisan actors.

“Just think about the implications of simply ignoring the results of an election,” says Kenneth Mayer, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Election deniers on ballot: What does this mean for democracy?

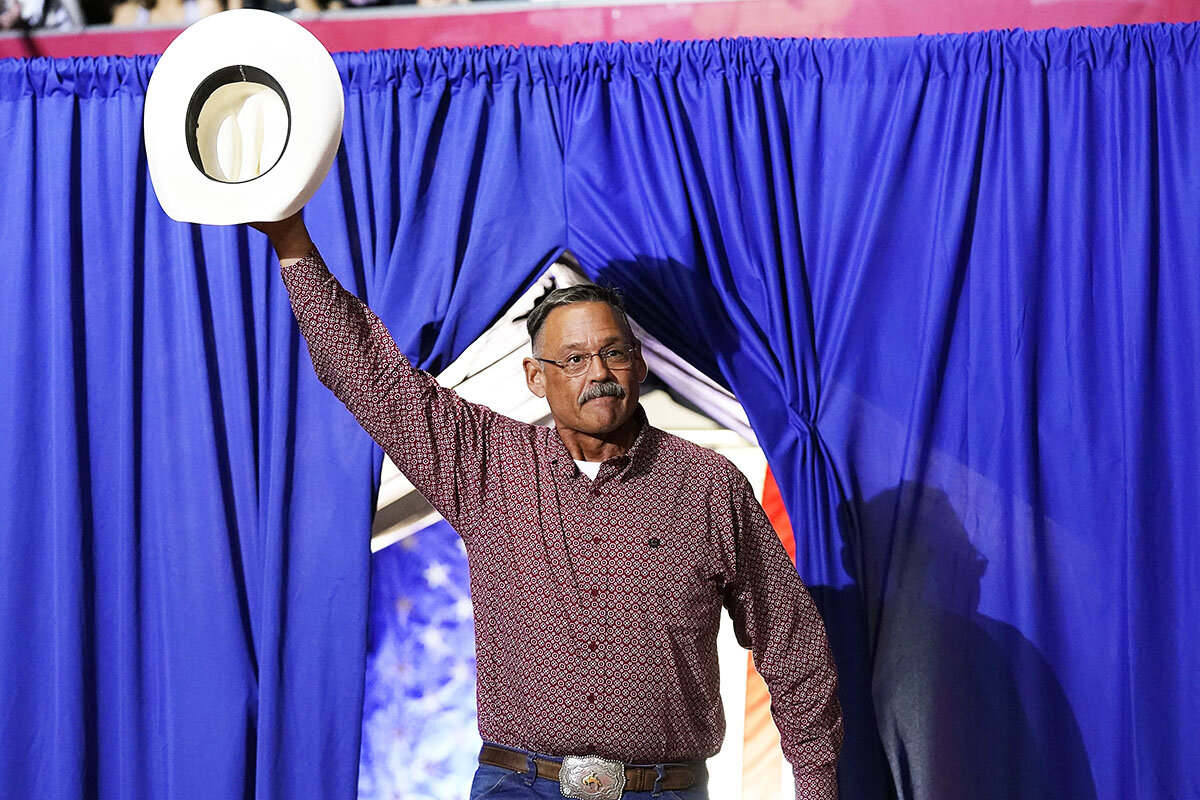

Mark Finchem, the Republican candidate to become Arizona’s top election official, secretary of state, has said he would not have certified President Joe Biden’s victory there in 2020.

Kristina Karamo, the GOP nominee for Michigan secretary of state, claims that the 2020 vote there was rife with fraud and that former President Donald Trump – not President Biden, who won the state by 154,000 votes – was the true victor of the state’s Electoral College votes.

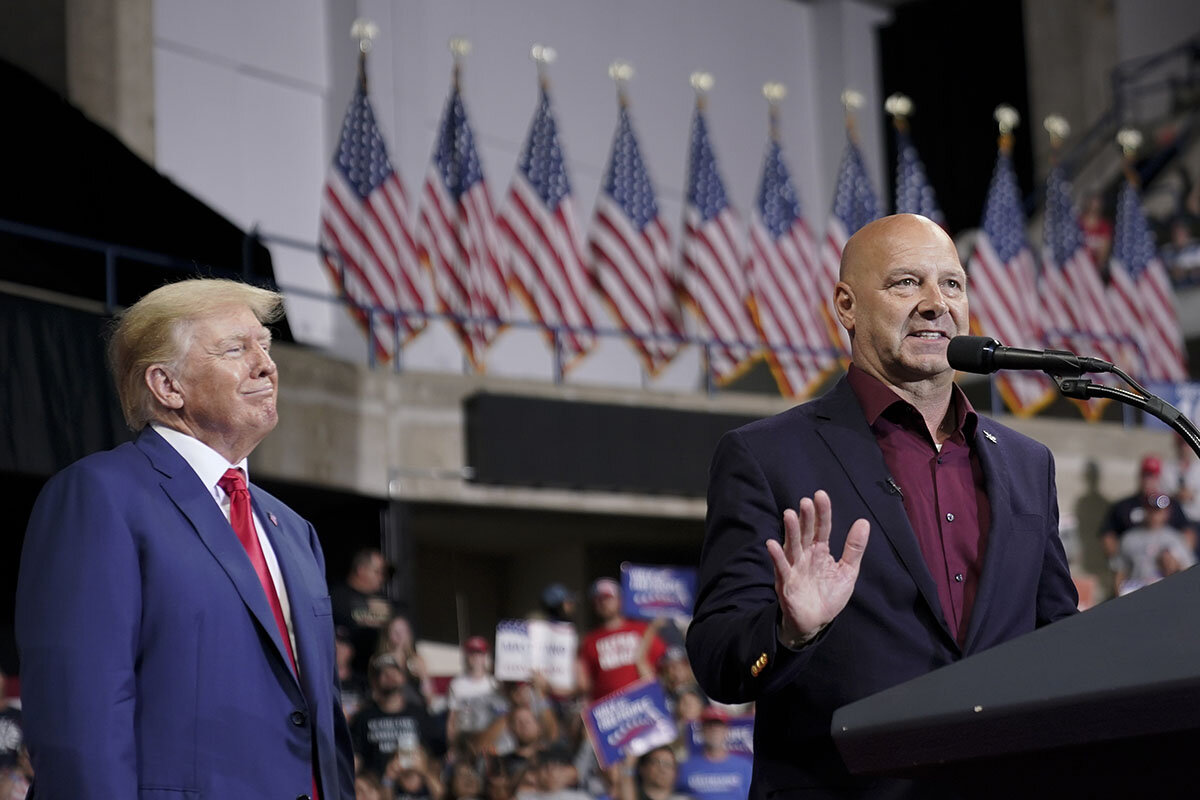

Doug Mastriano, Republican gubernatorial candidate in Pennsylvania, is a state lawmaker who introduced a resolution following the 2020 vote claiming that the election was “irredeemably corrupted” and the state legislature should appoint new delegates to the Electoral College. If he wins the governorship this November, Mr. Mastriano would have the power to appoint Pennsylvania’s next secretary of state.

Across America, Republicans who question the legitimacy of the last presidential election are on the ballot for the 2022 midterms. At least 195 GOP Senate, House, governor, attorney general, or secretary of state nominees have echoed Mr. Trump’s false charge that the presidential election was stolen, data media site FiveThirtyEight estimated this week.

Yet multiple reviews in state after state have shown the election to be fair and the results accurate. Multiple officials of both parties, including Mr. Trump’s former Attorney General William Barr, have said they saw no evidence of widespread fraud.

Whether election deniers in key positions could have flipped 2020 for Mr. Trump is an open question. The U.S. electoral system is decentralized and complex. Nor is every candidate who criticizes the last presidential vote embracing disinformation or false claims. For many, it may be a way of expressing anger at the 2020 outcome or continued support for Mr. Trump.

But Mr. Trump – who seems almost certain to run again – continues to push his false claims of widespread fraud at rallies and on his Truth Social media site. If in 2024 the election is razor-close, and a battleground state election official who echoes these claims refuses to certify a result or appoint Electoral College electors, trust in the election system, even in democracy itself, could be gravely damaged.

“Just think about the implications of simply ignoring the results of an election,” says Kenneth Mayer, a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

“This is going to remain a force”

In many ways Republican candidates who question the legitimacy of the 2020 election are simply mirroring what their voters believe. In poll after poll, about 70% of Republican voters say they do not think Mr. Biden legitimately won election to the presidency, according to the fact-checking site PolitiFact.

That does not mean a vast majority of the GOP accepts all the misinformation about 2020 that Mr. Trump continues to espouse. It’s possible some of this grassroots denialism represents disaffected voters expressing anger at the system, says Richard Pildes, a professor of constitutional law at New York University.

But expressing mistrust in the Biden-Trump contest’s result – despite more than 60 court decisions, official statements, and reports indicating it was conducted fairly – has become a foundational belief in particular for Republican primary voters, who are often the most motivated party faction. The result has been victories for candidates who embrace Mr. Trump’s “Stop the Steal” ethos in some key battleground states.

“I do expect that particularly in close elections, this is going to remain a force,” says Professor Pildes.

President Biden, in a speech billed as a defense of democracy last week, spoke for many Democrats and some Republicans when he criticized what he termed “MAGA Republicans” for not recognizing the will of the people and refusing to accept the results of free elections.

“They’re working right now as I speak in state after state to give power to decide elections in America to partisans and cronies, empowering election deniers to undermine democracy itself,” the president said.

GOP candidates who say they doubt the 2020 outcome were not happy with his words.

“I think he is too divisive calling his doubters horrible names. He should be trying to unite the country,” tweeted Mr. Finchem last week in response to the president’s speech.

The role of secretary of state

Of 529 Republican nominees for top offices in the upcoming 2022 midterms, 195 have fully denied the results of 2020, according to FiveThirtyEight’s analysis. That means they either directly stated that the vote was stolen or joined in legal action to try to overturn the results.

An additional 61 nominees have raised questions about the presidential election, according to FiveThirtyEight, meaning they have expressed doubts that the vote was conducted fairly without openly questioning whether the election was legitimate.

The majority of these are House candidates, and many are poised to win. In office, they could vote to challenge state results in 2024 when Congress, per the Constitution, meets to certify the election of the president – as 147 did on Jan. 6, 2021.

But it is the prospect of election-denying candidates winning state offices – governor, attorney general, and secretary of state – that worries some experts the most. Of those, secretary of state may be the most vulnerable to electoral mischief. They are the top election officials in many states, setting rules and regulations, approving voting procedures, overseeing worker training, and certifying results.

“There’s a lot of room for them to put their thumb on the scale,” says Professor Mayer.

Secretaries of state could change how people vote in many states, pushing to eliminate or curtail drop boxes and the use of voting by mail, or electronic voting machines. They could expand access for partisan election observers, or increase the presence of law enforcement at precincts. They could discourage voting and erode trust in elections by continuing to question the electoral system.

Among the most disruptive things secretaries of state could do is refuse to certify accurate results, or acquiesce in objection to certification from lower-level officials. If such officials in just three battleground states won’t certify their results or appoint electors, the nation could face a constitutional crisis.

“One of the things that 2020 has driven home is the magnitude of insider threats to election integrity,” says Philip Stark, professor at the University of California, Berkeley and an election integrity expert.

“We have to play their game better”

There are nine Republican secretary of state nominees who fully or partially embrace false assertions about the prevalence of fraud in 2020 elections, according to a race-by-race analysis of American election candidates by Bloomberg News.

One is already guaranteed election this fall. In Wyoming, GOP candidate Chuck Gray is running unopposed in November’s general election. Mr. Gray has called the 2020 election “clearly rigged,” and has asserted that the “woke, big tech left” steals elections.

Four of them represent crucial battleground states and have joined together in an America First Secretary of State Coalition: Mr. Finchem in Arizona, Ms. Karamo in Michigan, Jim Marchant in Nevada, and Mr. Mastriano in Pennsylvania. The last, while a gubernatorial candidate, says he has already selected a suitable person for secretary of state.

Their website states that their goals are to achieve “voter integrity” and “counter and reverse electoral fraud.” While instances of fraud can be found, many experts say it is rare in America and limited to isolated incidents that would not affect an election’s outcome.

Their agenda includes eliminating mail-in ballots while keeping traditional absentee ballots – presumably for voters with an excuse as to why they cannot vote in person. They also favor single-day voting, poll-watcher reforms, aggressive “cleanup” of voter rolls, paper ballots, and a voter identification requirement.

“In order to win, we have to play their game better. If we want fair and honest federal elections, we must start with electing the right people at the State level,” says the America First Secretary of State Coalition website.

Different forms, but all “destabilizing”

There are many different forms of election denialism, says NYU’s Professor Pildes.

Some people say they wouldn’t have certified the 2020 election, he says. Some would say that Mr. Biden is president, but without saying he won. Some say there was fraud and the election will never be certain for that reason.

But “I’m not sure how much difference it makes to distinguish between these different versions because they’re all incredibly destabilizing,” he says.

The U.S. election system is very decentralized, even for national elections. Many different levels of government have a hand in administering the vote. Key officials who oversee elections are themselves elected, meaning they can become partisan actors.

And we’re in a period where many people on both sides believe our elections are existential matters, and that if the other side wins, the country will never be the same, says Professor Pildes.

“When people come to believe that, their willingness to take measures that they might not take under normal circumstances becomes heightened,” he says.

Monitor Breakfast

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona on debt relief and teacher shortages

From teacher shortages to student debt forgiveness, education in the United States is in the news. At a Monitor Breakfast, Education Secretary Miguel Cardona offered both critiques and solutions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Financing education was a major topic of discussion at today’s Monitor Breakfast conversation between reporters and Education Secretary Miguel Cardona. He made no apologies for the recently announced student debt forgiveness plan, saying, in essence, that what benefits some, benefits all.

“The intent of this debt relief is to make sure borrowers are not worse off after the pandemic than they were before,” Dr. Cardona said. “But to that person that paid off their loan, having their neighbor not go into default helps the local economy.”

The secretary has a long and wide-ranging background in education, beginning with teaching fourth grade in Meriden, Connecticut, then serving as principal, assistant superintendent, and finally as the state’s education commissioner, before joining the Biden administration in March 2021.

Asked about his criticism of the college ranking system, Dr. Cardona described a system “that rewards exclusionary practice.”

“There are millions of students out there with tremendous potential – many of whom are the first in their family to go to college – who won’t even be looked at by some of these universities.”

“I’m interested in developing and evolving our system of higher education to promote and reward inclusionary practices,” he added.

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona on debt relief and teacher shortages

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona has a message for Americans who paid off their student loans and aren’t eligible for the federal government’s new debt forgiveness plan.

When asked at a Monitor Breakfast for reporters Wednesday how the plan is fair, he answered, in essence, that what benefits some, benefits all. He compares the program – which is just gearing up and may face legal challenges – to the Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP, the government loans that kept businesses afloat during the height of the pandemic.

“The intent of this debt relief is to make sure borrowers are not worse off after the pandemic than they were before,” Dr. Cardona said. “But to that person that paid off their loan, having their neighbor not go into default helps the local economy.”

“We’re not complaining that businesses weren’t forced to shut their doors and we provided support for businesses through PPP,” the education secretary added. “Now we’re investing in Americans to make sure they get back on their feet and move on with their lives.”

Dr. Cardona expressed confidence in the legality of the student debt forgiveness program. Last year, both President Joe Biden and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi had asserted that congressional approval would be required to fund student debt relief – with cost estimates to the federal government of between $300 billion and $500 billion. (Individuals making under $125,000 – and married couples earning under $250,000 – a year are eligible for $10,000 in debt forgiveness, or $20,000 in relief from Pell Grants.)

Now, the Biden administration is basing its ability to bypass Congress on a law passed in 2001 aimed at responding to war or another national emergency.

“Under the HEROES Act, I do have the ability to waive certain provisions to ensure that students are not worse off after the pandemic than they were before,” Dr. Cardona says, referring to the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act.

The education secretary says he “would welcome Congress’ action on this, because it is an issue that affects all Americans.”

And what about the underlying structural issues of how higher education is funded in this country, a system that has become increasingly unaffordable to people of modest means?

Dr. Cardona points to other efforts to make postsecondary education more affordable. One initiative involves income-driven repayment, which would cut student loan payments from 10% of a person’s income to 5%.

The education secretary brought to the table his background as an educator in Meriden, Connecticut – first as a fourth grade teacher, then as a principal and assistant superintendent, and finally as the state’s education commissioner, before joining the Biden administration in March 2021.

From his days as a principal, Dr. Cardona recalls a “really bright” boy in the sixth grade whose father declared that his son would not be going to college. “I just can’t afford it,” the man told him.

“The parent made a decision based on the fact that he knew he couldn’t afford college, you know – six years later that his son wasn’t going to college,” Dr. Cardona says. “That happens too often across our country. So we’re proud of the debt relief.”

The C-SPAN video of our breakfast with the education secretary can be viewed here.

Following are more excerpts from the breakfast, lightly edited for clarity:

What are other ways to fix the “broken system” of higher education financing?

Public service loan forgiveness. If you choose a profession where you’re serving the public, in many cases, you don’t do that because it pays like the private sector. You’re doing it to make the community better. So we’re making sure that the public service loan forgiveness law is implemented correctly.

When I became secretary of education, there was a 98% denial rate for public servants who paid their loans for 10 years, who served the public for 10 years and applied for this. Within a year of our fixing the broken system, we provided over $10 billion in loan forgiveness. Over 175,000 people have benefited from it.

We’re fighting to double Pell Grants so that more students who have maybe less resources growing up still have college accessible to them.

We’re going to be working very closely with our higher education institutions to ensure that we’re lifting up those universities that provide a good return on investment for students. You know, the days of going to college and leaving with $150,000 in debt and then getting a job paying $35,000 a year doesn’t cut it.

You recently referred to college ranking systems as a “joke,” taking particular aim at the most selective colleges’ obsession with rankings. What is it that gets under your skin?

There are millions of students out there with tremendous potential – many of whom are the first in their family to go to college – who won’t even be looked at by some of these universities.

I believe we have a system that rewards exclusionary practice. I’m interested in developing and evolving our system of higher education to promote and reward inclusionary practices. I don’t have to tell you that when students graduate, we still have disparities in achievement. The NAEP [National Assessment of Educational Progress] – the nation’s report card – is a symptom of the fact that in our K-12 systems, race in places still serves as a determinant of success, sadly, almost as a predictor.

Right now, an infusion of federal cash is helping K-12 schools. But what happens when that funding ends?

Federal spending on education makes up about 10% of education funding total. My challenge is to the other 90%: Match the president’s urgency. If we go back to the funding that was there in March 2020, we should not expect different results.

And how will a potential funding shortfall affect teacher “pipeline” programs, meant to address a shortage of K-12 teachers?

I’m visiting Tennessee next week as part of the back-to-school tour. I’m excited about that. Tennessee has a tremendous apprenticeship program, a Grow Your Own program that’s embedded throughout the state where it’s much like an apprenticeship for a trade.

They’re looking at solutions, viable solutions that are long term. There has to be an investment in those programs by states.

My push is not only to make sure we’re using the federal funds to create programs, but also to elevate the urgency in state and local governments on ongoing funding on those issues that are so important.

In Jackson, a crisis of water – and a broken social contract

Residents of Mississippi's capital city are without drinkable water from their taps. The story isn't just about recent floods. It's about decades of underinvestment fueling questions about equity and public trust.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

In Jackson, Mississippi, residents are having to rely on federal and state aid for drinking water in the wake of recent floods that caused a water treatment plant to fail. Yet even before this, Jackson residents were under a boil-water advisory because the city was unable to guarantee water safety.

Those who call this heavily Black city home say they’ve begun to feel left behind. And although the case of Jackson is extreme, such gaps based on race as well as income persist even in a nation where access to clean water is mostly taken for granted.

Experts say Jackson's need for $1 billion or more in water system upgrades is a problem decades in the making. Tax revenue sagged as many white and middle-class residents left the city starting with 1960s turmoil over civil rights and desegregation.

To win back public trust, the effort must stretch beyond city leaders, says Mukesh Kumar, a former Jackson planning official. It’s an investment that should be made collectively. “Meaning that the city of Jackson doesn’t just belong to the people who live in the boundaries. ... It’s a problem that exists for the state, that exists for the country as a whole.”

In Jackson, a crisis of water – and a broken social contract

This isn’t how Marie McClendon envisioned her Friday afternoon. Ahead of her vehicle is a long line of cars, idling in an abandoned mall’s parking lot in Jackson, Mississippi. It’s a dystopian scene, albeit with National Guard members scurrying about the open space to offer aid. Each car receives two cases of bottled water. She fans herself, shakes her head, and moves up in line.

Ms. McClendon grew up in Meridian, a city about an hour and a half away from the Mississippi capital here in Jackson. Ms. McClendon, her fiancé, and her daughter relocated to Jackson six years ago. Access to clean, safe drinking water has become a defining issue during their family’s time here. In fact, residents have been under a citywide boil-water notice since at least late July. As their family learned, the city’s boil-water notice was just a hint of the challenges to come.

Early last week, as the region flooded, the city’s O.B. Curtis Water Treatment Plant failed, leading to a chemical imbalance in the city’s drinking water supply. The system failure indefinitely eliminated Jacksonians’ access to clean drinking water. Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves declared a state emergency the next day; roughly 600 National Guard members were deployed to help distribute bottled water to the city’s residents. President Joe Biden then declared a national emergency that authorized the coordination of the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, to join in the city’s aid.

Even amid the state and federal efforts to help, those who call Jackson home say they’ve begun to feel left behind. The sense of being second-class citizens in their own state’s capital is particularly stinging because this is a heavily Black city, so the water failure cuts along racial lines. And although the case of Jackson is extreme, such gaps based on race as well as income persist even in a nation where access to clean water is mostly taken for granted. A 2019 report from the Natural Resources Defense Council found that drinking water systems that constantly violated federal safety standards were 40% more likely to occur in places with higher percentages of residents of color.

“I ain’t never seen nothing like this,” Ms. McClendon says, pointing to guard members as they heave cases of water into the car in front of her. “With this being the capital, the government should have never let it get this far.”

Decades of demographic change

Unlike last week’s flooding, the city of Jackson’s dysfunction didn’t occur overnight. Its water system woes were decades in the making, local officials and urban planning experts alike say.

In 1960, Jackson boasted a population of roughly 148,000 – of whom 64% were white, 36% African American. But in a decade marked by civil rights bills and school desegregation, as well as the resulting racially charged backlash across the country, a white-led exodus from Jackson and other American metropolitan cities ensued. In later decades, while Jackson reached a 1990 peak of roughly 200,000 citizens, rising crime became a factor that contributed to further losses of Jackson’s middle-class population to the surrounding suburbs.

The tax base that was the city’s foundation – which funds Jackson’s water and other public systems – began to disintegrate. Today, income for roughly 1 in 4 Jackson residents is below the federal poverty line. Its racial demographics have also shifted. About 16% of the city’s roughly 163,000 population today is white; 82%, Black.

“This is a set of accumulated problems based on deferred maintenance that’s not taken place over decades,” Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba said in a press conference last week, referring to the underfunding the city experiences as officials work to help systems keep pace.

Mayor Lumumba estimated that the city’s water system requires up to $1 billion in repairs.

Former city employees worry that the mayor’s recent estimate is too low, given that the Jackson water system encompasses more than 1,500 miles of water mains across its sprawling space.

Mukesh Kumar ran Jackson’s Department of Planning and Development from 2017 to 2019. Until a recent move to Waco, Texas, he was also a professor of urban studies at Jackson State University. In his recollection of internal conversations during his time employed with the city of Jackson, Dr. Kumar recalls officials citing estimates of up to $2 billion in needed investments.

The city’s annual budget hovers around roughly $300 million.

Chronic underfunding for infrastructure was matched, experts say, by a deeper fraying of the social contract between the city and community.

One way to view a city, Dr. Kumar says, is as a set of institutions that creates an enabling environment in which a community can thrive. If functioning well, one basic result of this social contract is to confirm and support the dignity that citizens have.

“Water systems, police, the roadways – they all end up being part of that enabling infrastructure. ... That’s what that social contract often presents,” Dr. Kumar says. “Once you lose that, it takes a long time to rebuild. It’s a very slow process. It’s not something that happens overnight.”

A recent survey by Blueprint Polling, an associate company of the Mississippi-based Chism Strategies, suggests that city and state elected leaders alike face a tough road ahead in regaining citizens’ trust. Of the nearly 500 Jackson residents who were included in the phone survey last week, roughly 55% agreed that Governor Reeves’ handling of the crisis was either totally unacceptable or poor. Mayor Lumumba registered slightly better with the survey’s respondents, as nearly 47% of those included said that his response was either totally unacceptable or poor.

“They’ve lost my trust”

The poll suggests a breakdown in trust – the core of that unspoken social contract. In interviews, Jackson residents confirm that feeling.

“It’s very bad,” says Kim Baptiste, a Jackson resident who recently relocated from Dallas, of the current state of the city. “How can you fill a pot with dirty water to boil it? That’s just crazy.”

It’s Friday afternoon, and Ms. Baptiste is hoping to have the water turned on in her new apartment in town, even if the water has been deemed unsanitary. That’s what’s brought her to the front steps of Jackson’s Water and Sewage Administration’s office during her lunch break. (Over the weekend, the city said water pressure has been restored to most city customers.)

In a rush, she strides over to the building’s doors and jerks on them twice. It’s part of the same abandoned mall complex from which National Guard members are distributing bottled water. However, the building’s doors are locked. A Water and Sewage Administration employee walks over to Ms. Baptiste and the others standing outside to tell them the office closed early for the afternoon due to the office’s air conditioning system not working.

Ms. Baptiste describes the afternoon as one that’s typical of her time in Jackson so far.

Cathy Johnson, a lifelong Jackson resident, is also locked out of paying her water bill today. Like Ms. Baptiste and others, she, too, was turned away during the time she’d taken from her lunch break. “It’s sad that you go to get the feds to come in and fix your stuff,” she says.

To win back public trust, the effort must stretch beyond city leaders, Dr. Kumar says. It’s an investment that should be made collectively. “Meaning that the city of Jackson doesn’t just belong to the people who live in the boundaries,” Dr. Kumar explains. “It’s a problem that exists for the state, that exists for the country as a whole.”

The road to recovery for Jackson likely consists of a 10-to-20-year project that will call for the replacement of old pipes and upgrading treatment plants. In December, the Environmental Protection Agency announced that nearly $75 million in federal water and sewer infrastructure funds would be made available to Mississippi this year through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

In the eyes of many here, the federal funding came too little, and too late.

After her wait, Ms. McClendon is at the front of the bottled water distribution site. She’s hot, tired, and busy – and she knows it likely won’t be her last wait for bottled water in coming days.

She leans over her steering wheel and sighs. “They’ve lost my trust,” she says, referring to the city. “They shouldn’t have let it get this far.”

No Paris? No problem! Russian tourists holiday in the homeland.

Amid war and sanctions, Russians have been cut off from many of their preferred vacation spots this summer. That has spurred a boom in travel to destinations within their own vast homeland.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Despite six months of intense sanctions against Russia, the ruble is strong, incomes are buoyant, and domestic transportation is functioning well.

But Russians who want to go on vacation are finding traditional destinations less accessible, due to the increasing difficulty of obtaining visas, the closure of airspace to Russian airlines, and the fact that Russian bank cards no longer work abroad.

Hence, a rush to discover Russia is on.

Tour operators report a surge in bookings, especially for traditional destinations like Volga river cruises and beach holidays in the Black Sea resort centers of Krasnodar and Sochi. In Moscow, there are more Russians than ever walking around Red Square, wandering through museums and galleries, and taking selfies in iconic metro stations. Other rich cultural centers like St. Petersburg are seeing similar booms.

“We expect up to 45 million Russians to travel inside the country this year. That’s ten times the number going to Turkey, which is the major foreign destination that’s still open to Russians,” says tour agency director Sergei Romashkin. “We’re seeing people going to the Far East, to Siberia, the North Caucasus, Karelia [on the Finnish border], and Kaliningrad [on the Baltic Sea]. Completely new destinations have suddenly become quite fashionable.”

No Paris? No problem! Russian tourists holiday in the homeland.

Each day, people from all over Russia tramp up several flights of stairs in an old apartment building in central Moscow. On the way, they often stop to gawk at the thick layers of fantastic, metaphysically themed graffiti, much of it dating from the Soviet era, scrawled by generations of Muscovites.

At the top of the stairwell is one of Moscow’s most popular tourist destinations, the memorabilia-stuffed former communal apartment where the author Mikhail Bulgakov lived and worked a century ago. Today it is a state museum, the graffiti on the stairs a sign of locals’ appreciation for Bulgakov’s beloved, sometimes absurdist, philosophical writings.

And there’s been a significant surge in visitors this year as Russians, increasingly frustrated in their hopes of traveling abroad, turn their attention to discovering their own country, says Alexei Yakovlev, deputy director of the Bulgakov State Museum.

Despite six months of intense sanctions, the ruble is strong, employment and incomes are surprisingly buoyant, and domestic transport networks are functioning well. But the vacation-minded are finding traditional destinations much less attainable than before, due to the increasing difficulty of obtaining visas in many countries, the widespread closure of airspace to Russian airlines, and the fact that Russian bank cards no longer work beyond the country’s borders.

Hence, an apparent rush to discover Russia is on. And the apartment-museum dedicated to Bulgakov – the most widely read author in Russian high school curricula, and whose focus on basic moral questions may resonate in these vexed times – is just one of those attractions benefiting.

“Bulgakov was concerned with what makes a person whole; his work is all about people on the verge, needing to make choices,” Mr. Yakovlev says. “He lived amid civil war, the coming of Stalinism, and some may feel that the times are similar. So, his importance is growing. We try to avoid addressing contemporary political issues head on, because there could be forces that might want to use us for their own purposes. We focus on literature, science, memory, and let Bulgakov’s legacy speak for itself.”

Exploring the motherland

Tour operators report a surge in bookings, especially for traditional destinations like Volga river cruises and beach holidays in the Black Sea resort centers of Krasnodar and Sochi – although wartime conditions and Ukrainian attacks have reportedly caused a sharp reduction in travel to the recently annexed territory of Crimea.

And in Moscow, there are a lot more Russians than ever walking around Red Square, wandering through the city’s famed museums and galleries, and taking selfies in its iconic metro stations. Other rich cultural centers like St. Petersburg and the central Russian “Golden Ring” constellation of ancient cities, with their ornate kremlins and fortress-like monasteries, are seeing similar booms.

“We expect up to 45 million Russians to travel inside the country this year. That’s ten times the number going to Turkey, which is the major foreign destination that’s still open to Russians,” says Sergei Romashkin, director of the Moscow-based Delphin tour agency. “In the past Russians have thought of travel mostly in terms of going abroad, because it seemed more exotic, and conditions were usually much better than at home. For a variety of reasons, a shift is taking place, and it might well become permanent.”

Tour operators also report surprisingly strong demand, especially among young people, for a host of domestic destinations that have never been regarded as places worth visiting by most Russians – and where local people have little in the way of hospitality industry and tourist infrastructure to receive them.

“We’re seeing people going to the Far East, to Siberia, the North Caucasus, Karelia [on the Finnish border], and Kaliningrad [on the Baltic Sea]. Completely new destinations have suddenly become quite fashionable,” says Mr. Romashkin.

Nation of destinations

If you had to be confined to a single country, Russia, the world’s largest nation by territory, wouldn’t be a bad choice – at least from a tourist’s point of view.

On its wild Pacific coast, the California-sized Kamchatka Peninsula is a land of virgin forests, volcanoes, and giant bears.

At the heart of Siberia is Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest lake, which was once declared sacred by Mongol warlord Genghis Khan. Around its shores are flourishing communities of indigenous Buddhists and Old Believers who were once banished to Siberia by the czars.

Kazan, a Tatar city on the Volga, is fast becoming another magnet for Russian tourists attracted to its sandy river beaches and the only kremlin in Russia that features a giant mosque at its center.

Russia’s northern Caucasus region, until recently engulfed in war and terrorism, is emerging as an unexpected tourist attraction. Tour operators say that even Dagestan, until recently a virtual no-go zone where visitors were more likely to be kidnapped than welcomed, has become a major destination for young Russians attracted to its mountain trails, ancient ruins, and sandy Caspian Sea beaches.

Another newly popular region is Russia’s European Arctic, where adventurous tourists can view the Northern Lights or take a ride on a nuclear icebreaker.

Russia’s Baltic exclave of formerly German Kaliningrad boasts Prussian architecture and miles of Baltic Sea beaches.

“No one wants to be shut in”

Sarah Lindemann-Komarova is an American who’s lived in Siberia for almost 30 years. She resides in Altai, an impoverished mountain republic abutting the border with Mongolia. In 2019, it saw about 2 million tourists, including many foreigners. This year the number has doubled, but it’s only Russians who are coming, mostly on newly inaugurated flights from Moscow and St. Petersburg. Prices have gone through the roof, and infrastructure is challenged, she says.

“Our village of Manzherok was a sleepy, poor backwater when I first came here in 2001,” she says. “Only a few nature-loving visitors appreciated the region, which some people referred to as the Switzerland of Russia. Now those people are horrified by the traffic jams and the loss of solitude. ... But it is providing a real economic boon for local people. Many villagers have been transformed into small business owners, building cabins to rent, offering various services. This is a community in transition.”

It’s hard to know whether the trend will be a lasting one, especially if the world should open up for Russians again. Mr. Yakovlev of the Bulgakov Museum says it’s fortuitous that external pressures are forcing Russians to discover their own country, and it’s hard to argue with the economic stimulus tourism can bring to once-neglected far-flung Russian regions.

“Maybe for now people aren’t really feeling the effects of enclosure, because it’s all so novel and this is an awfully big country,” he says. “But eventually it’s going to have an impact. No one wants to be shut in and isolated the way we were in the Soviet Union.”

Difference-maker

At Fly Compton, the sky’s not a limit. Neither is race.

In an industry with an underrepresentation of minorities, a group of Black professionals is passing along skills to the next generation of potential aviators.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Marlon L. Dwight Contributor

As teachers and role models, the aviation professionals at Fly Compton Aero Club know the value of their Black faces to the young people who come to them to learn how to fly. Their nonprofit foundation in Los Angeles County puts Black and Latino youths at the cockpit controls and on Saturdays schools them in aerodynamics, air traffic control, and other subjects.

Major companies across the U.S. aerospace industry have launched initiatives to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workforce, and Fly Compton is committed to supporting those efforts at the pipeline level.

A former stockbroker, political consultant, and current president of Fly Compton, Demetrius Harris was well into adulthood before being inspired to pursue a career in aviation after boarding a flight to travel abroad.

“Both of the pilots were African American,” Mr. Harris recounts. “And I’d never seen even one African American pilot at a commercial airline before. That visual unlocked my motivation to want to become a pilot.”

At Fly Compton, the sky’s not a limit. Neither is race.

“I was really nervous,” says 11-year-old Yeshaya Lang. “I don’t really like curves and stuff. Like [not even] roller coasters.”

A year ago, Yeshaya was anticipating the ups and downs of a single-engine airplane – with his own hands at the controls as a student pilot for the first time.

“I was like, ‘What if we crash?’”

At Compton/Woodley Airport where Yeshaya takes flying lessons, students pilot short excursions over the neighboring city of Carson with Fly Compton Aeronautical Education Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to guiding marginalized youth into the aviation industry. It’s affordable access to professional education for careers that might otherwise be inaccessible.

But Yeshaya wasn’t thinking about his professional future as much as the Piper PA-28 Cherokee right in front of him at that moment. So he told himself, “A bunch of other kids do this a lot, and nothing’s ever happened.”

His flight went off without a hitch. So too did his second flight weeks later. On his third flight, the anxiety that had nagged at him was no more.

It’s confidence gained in an atmosphere created by professionals trying to remove some of the barriers to aviation. Across the board, the kids who enroll at Fly Compton already defy commonly held perceptions of Black and Latino youths in the United States. For Yeshaya, that means being the son of a psychologist and a Boeing executive who learned about Fly Compton through work. But as a function of systemic financial and social barriers that limit access to educational resources largely on the basis of race, these young people still commonly encounter barriers that their white counterparts do not.

“[It’s] about educational access,” says Alex Barker, Fly Compton Aero Club’s chief certified flight instructor.

While representing 12.3% of all U.S. workers 16 years and older, African Americans made up only 3.9% of U.S. aircraft pilots and flight engineers in 2021, a tiny increase over a decade ago, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor stats for Latino, Asian American, and female pilots and flight engineers during the same periods are comparably low.

Major companies across the U.S. aerospace industry have launched initiatives to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workforce – among them Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, Northrop Grumman, and Lockheed Martin. American Airlines, for one, has begun to employ graduates of its Cadet Academy – a project designed to train and lend other critical support to prospective pilots, with people of color and women as principal areas of focus.

Creating an atmosphere of support

For its part, Fly Compton is committed to supporting those initiatives at the pipeline level.

“What we’re trying to do is get all of these commercial airline companies and airplane builders to invest just a little to help diversify the industry that they, themselves, say they want to diversify,” says Demetrius Harris, Fly Compton president and executive director.

Students at Fly Compton are instructed using a curriculum similar to what they would encounter in an aviation program at a college or university. In person and via Zoom on Saturdays, over the course of nine months, Fly Compton students are instructed in subjects such as principles of flight, aerodynamics, airplane engine systems, weather, and air traffic control communications. The course costs students an annual enrollment fee of $125, plus $25 each month.

Fees at private aviation undergraduate institutions are high, explains Mr. Harris.

“The total cost to get a commercial license can range based on a number of factors, such as how often a student trains or how quickly they are able to grasp all of the concepts,” he says, noting that Fly Compton’s hourly rates to rent planes to adults for instruction are 15% to 20% lower than those offered by other flight schools in Southern California. “Our goal is to continuously fundraise from corporations and government entities to provide scholarships for training to our students to help mitigate the high costs.”

As the son of an air traffic controller growing up in Orange County, California, Mr. Barker, the flight instructor, had always been fascinated by aviation. Yet he never imagined that becoming a pilot was an attainable goal. Typically, in the U.S., pilots pursue either a military or civilian path.

But after earning a college degree in geology, working odd jobs, and starting a family of his own, he pursued his pilot’s license. After earning his ratings (which authorize pilots to fly specific types of aircraft), he elected to become a certified flight instructor. He discovered Fly Compton Aero Club, the for-profit flight school affiliated with the Fly Compton nonprofit. Upon meeting the team, he knew he had found a home.

Role modeling

A key benefit for students at Fly Compton is the opportunity to meet with Black aviation professionals – people who have succeeded in the industry, whom the students themselves might hope to one day join.

This includes people like Fly Compton advisory board member Tony Marshall, a retired U. S. airman and former prisoner of war who flew for the Air Force during the conflict in Vietnam; Fly Compton Director of Operations Ronnel Norman, a pilot for Alaska Airlines; and Jonathan Strickland, who pilots for UPS and started flying at age 12.

A former stockbroker and political consultant, Mr. Harris was well into adulthood before being inspired to pursue a career in aviation in 2018 after boarding a flight to travel abroad.

“Both of the pilots were African American,” Mr. Harris recounts. “And I’d never seen even one African American pilot at a commercial airline before. That visual unlocked my motivation to want to become a pilot. And literally three months after that, I was in flight school.”

Mr. Harris has piloted corporate jets for a number of celebrities and other high net worth individuals. But the work he does with Fly Compton is where his heart lies: “Honestly, I love it. I’ve had my experience flying jets, and it’s great. But this is more fulfilling to me. This is where I feel like I can make the most difference.”

For Yeshaya, Fly Compton was a key part of a memorable final year of elementary school packed with student council and sports activities and academic and citizenship awards. While he begins middle school with a strong knowledge of a potential career in aviation, Yeshaya says he’s uncertain about exactly what career he wants.

But when asked what he thinks about becoming a pilot, his eyes light up: “I think it would be a fun job.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Left or right, Latin Americans find their voice

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Five years ago, much of Latin America broke right, electing conservative governments that promised to tackle corruption and rising crime. Now it appears to be swinging the other way. If Brazilians return former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to power on Oct. 2, the region’s six largest economies will be governed by leftists for the first time.

There may be less – and more – to that than it sounds. Voters aren’t shifting back and forth between ideologies. They are eagerly searching for greater social equality, more economic opportunity – and, above all, better competency in governance.

The new leaders of Latin America face stiff headwinds and short leashes. They have come to power promising social justice and green economies. But they have little room to maneuver amid crises of inflation, food insecurity, and most of all, voters who are both impatient and weary of government overreach.

That last point was made clear in Chile on Sept. 4 when voters soundly rejected a proposed, broadly leftist constitution. “We must listen to the voice of the people and walk alongside the people,” said President Gabriel Boric.

Left or right, Latin Americans find their voice

Five years ago, much of Latin America broke right, electing conservative governments that promised to tackle corruption and rising crime. Now it appears to be swinging the other way. If Brazilians return former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to power on Oct. 2, the region’s six largest economies will be governed by leftists for the first time.

There may be less – and more – to that than it sounds. Popular demands have expanded but they haven’t changed. Eighty-five percent of Latin Americans thought corruption was a big problem before the pandemic, according to Transparency International. COVID-19 deepened that crisis of public trust. So have climate change and inflation. Voters aren’t shifting back and forth between ideologies. They are eagerly searching for greater social equality, more economic opportunity – and, above all, better competency in governance.

Those expectations mark an important shift from a half-century ago when the region seemed stuck in historical grievances. “Our defeat was always implicit in the victory of others,” wrote Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano at the time. Now Latin Americans are more apt to recognize their own “silence of complicity, of fear, of hiding” against brutal or dishonest regimes, as Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra put it to The Atlantic through his translator.

Recent protest movements have ushered in new types of leftist governments, reflecting a newfound agency to build a new society rather than simply tear down the old. “A perspective is opening up that undoubtedly has to be taken advantage of,” wrote Andrés Allamand, the Chilean Ibero-American secretary-general in a “message or optimism” this week.

The new leaders of Latin America face stiff headwinds and short leashes. Like Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, they have come to power promising social justice and green, post-carbon economies. But they have little room to maneuver amid crises of inflation, food insecurity, unpredictable weather, and most of all, voters who are both impatient and weary of government overreach.

That last point was made clear in Chile on Sept. 4 when voters soundly rejected a proposed, broadly leftist constitution. The defeat forced a 6-month-old government to pause in its attempts at sweeping social and environmental change.

“I’m sure all this effort won’t have been in vain, because this is how countries advance best, learning from experience and, when necessary, turning back on their tracks to find a new route forward,” said President Gabriel Boric. “We must listen to the voice of the people and walk alongside the people.”

In a region where many citizens have found a voice for reform, leaders left and right have indeed had to listen.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Addressing negative self-talk

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Bobby Lewis

Negative self-talk comes to thought aggressively, suggesting we are inadequate. But we can counter it with the spiritual truth that we are made in the image of God, divine Mind, and therefore hear and respond only to His thoughts.

Addressing negative self-talk

As I walked north next to a railroad track, the uninvited words “You know nothing” intruded hard into my thought like a train coming out of nowhere. I paused, stood still for a moment, and then as if arriving on the tracks from the other direction another thought came to mind: “I know something of You, God, and You know everything of me. That is enough.”

This sequence of thoughts was illustrative to me. Negative self-talk often slams into our thinking and speaks unwanted messages to us. Sometimes it is tied to a situation in which we feel as though we could have done better, and other times (like for me that day) it is invasive but unattached to any particular circumstances. In either case, the question is: What can we do about it?

Part of the answer to silencing negative self-talk is not to internalize or agree to the suggestion that we are the source of self-deteriorative thoughts, because they are no part of our God-created spiritual individuality. Rather, we can separate these thoughts from ourselves and see them for what they are – erroneous intrusions, falsely suggesting that we have a self apart from divine Life, God, that can talk us down. This discouraging mental chatter feels personal, but the truth is, it’s not. It is an imposition on us and not something of our own creating, nor something that has the power to separate us from an awareness of our spiritual identity.

When negative self-talk is barging into thinking, it also helps to remember the account in Scripture where Moses asks God His name and the answer is: “I AM THAT I AM” (Exodus 3:14). With a thought like “I am incompetent,” for example, it’s appropriate to ask in prayer, Is this statement true about the I AM, God? The thought, “I AM incompetent” is certainly never something the divine Mind could or would think about itself.

The Bible’s first chapter, Genesis, states that we are created in God’s image (see Genesis 1:26). If a statement is not true about God, it cannot be true about His image either. From that place of establishing in prayer what is true about God, we have a foundation for recognizing what is true about ourselves, and what is not. We do this, day by day, by growing in our understanding of Spirit, God, and listening for the truth about who and what we are spiritually.

The Apostle Paul said that we “have the mind of Christ” (I Corinthians 2:16). And Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, wrote of man that he has “no separate mind from God” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 475).

We can recognize the true, divine voice in our thinking because it consistently speaks to us the truth about God and about us. In Scripture there is a passage where God is speaking and says, “My thoughts are not your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:8). Like with my experience by the railroad tracks, I find it helpful when a negative thought comes to ask in prayer, “Is this a God-thought?” If the thought is deteriorative and not from God, we can seek to set it aside by asking God to remove it from us through His truth. Then we can give it no more place in thought.

I saw a bumper sticker once that said, “Don’t believe everything you think.” We are empowered by God to recognize self-deprecating thoughts that do not have a divine source, and to reject and discard them as impostors not having an origin in us or power over us. The foundation for seeing ourselves clearly is to understand that true consciousness is inseparable from its source in divine Mind. What a sweet difference-maker that is.

A message of love

No. 10’s new occupant

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow when we look at why nuclear power is getting a fresh look around the world.