- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- All that nuclear talk: Is the unthinkable suddenly possible?

- When leaders don’t listen: Lessons from Liz Truss’ rise and fall

- How Xi Jinping is reshaping China, in five charts

- Evacuation orders, safety, and Florida’s hurricane culture

- Make them laugh: Dalit comics challenge caste, one joke at a time

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Where ingenuity keeps stoking progress

If you keep innovators in view, it’s hard not to feel at least a little optimistic.

I recently wrote in this space about a teen inventor in Florida who’s developing motors for electric vehicles that don’t rely on the extraction of rare-earth elements.

Now comes news that some Dutch students – with an eye to the carbon dioxide emitted in an EV’s entire lifespan, from manufacturing to recycling – have developed a prototype that can capture more carbon than it emits.

“They imagine a future,” Reuters reports, “when filters can be emptied at charging stations.”

Separately, in Amsterdam, autonomous boats roam, scooping river trash. In Portland, Oregon, Disaster Relief Trials train the riders of electric cargo bikes to deliver messages and supplies should a natural disaster break the city’s infrastructure.

Regions that lack communications infrastructure to begin with may get help from a U.S. startup making backpack-size solar-powered “cellular base stations” – essentially independent internet service providers. A pilot project is planned in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

And in response to deepening drought, a “modular” approach to seawater desalination was approved last week by California regulators. It will supply a small water utility south of Los Angeles. It passed muster with many environmentalists who’d opposed a larger private effort because of its projected effects.

“This could be replicated … up and down the coast,” an environmental scientist told Yahoo News.

Small steps, big ideas. All face hurdles and course corrections. All spring from daring to hope.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

All that nuclear talk: Is the unthinkable suddenly possible?

After World War II, the use of nuclear weapons was put behind an uncrossable red line. Do current world tensions threaten to put them back in play – or will international cooperation renew an old bulwark?

Since the bombing of Nagasaki in 1945, the world has observed a taboo on the use of nuclear weapons. It became unthinkable.

But now, Russian President Vladimir Putin has begun raising the prospect that he might use nuclear arms – albeit smaller-scale, tactical battlefield weapons – to defend Russian-held territory in Ukraine. And North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has shown signs of shifting his nuclear doctrine away from “no first use.”

This, against the background of a halt to landmark arms control treaties, and a shift among some military planners toward the use of small nuclear devices as a shock weapon in an “escalate to de-escalate” strategy.

That would take the world into unknown territory. Until now, the nuclear powers have used their weapons for their deterrence power. Mr. Putin is threatening to use them as a tool of coercion.

That is a rude awakening from three decades of post-Cold War complacency encouraged by declining fears that big-power nuclear confrontation could subject the world to a fearsome “nuclear winter.”

“Nuclear weapons never went away,” says Heather Williams, an expert at a Washington think tank. “The public just forgot about them.”

All that nuclear talk: Is the unthinkable suddenly possible?

First, Vladimir Putin raised the prospect of using nuclear weapons to further his aims in the war in Ukraine.

Then North Korea’s Kim Jong Un followed suit, announcing his field inspection of tactical nuclear weapons units. That seemed to confirm a change in nuclear weapons strategy Mr. Kim had hinted at earlier this year – from “no first use” to foreseeing the use of battlefield tactical nuclear weapons.

To many experts, the sudden crescendo in talk of nuclear weapons suggests an epochal shift in perception of the use of nuclear arms from unthinkable – remember Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev declaring in 1985 that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” – to possible.

“We are on the cusp of a third nuclear age that puts us in uncharted waters,” says David Cooper, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments in Washington and a former director of nonproliferation policy at the Pentagon.

After the Cold War era of nuclear competition between two superpowers, and then the post-Cold-War years of rising nuclear threats from regional powers, the world is back to great-power nuclear competition – with China added to the mix this time around, Dr. Cooper says.

Also dangerously characteristic of this third era: vanishing international cooperation on nuclear disarmament, and the destabilizing weakness of one of the nuclear powers, Russia.

Mr. Putin’s threats suggest that this new era has the potential for a creeping normalization of nuclear weapons’ use, some experts say – and for increased recourse to nuclear blackmail by countries like Russia (or North Korea) facing adversaries with significant conventional military advantages.

Moreover, the burgeoning public discussion of nuclear arms use and behind-closed-doors plotting of their place in battlefield scenarios suggest to others that the use of nuclear weapons is no longer necessarily seen as a moral issue.

“We have had this idea of a moral taboo” on using nuclear weapons, Dr. Cooper says. Under what he calls the “optimistic scenario” for today, that taboo is still operative, he says.

But “if the genie is out,” he adds, “we are back in a very dangerous nuclear landscape.”

A nuclear game changer

Yet despite these disquieting trends, the eight-decade-long proscription against nuclear weapons use has not been breached. While that offers hope, some say, it also adds urgency to diplomatic efforts to convince Mr. Putin and others not to cross the line.

President Putin “is not the only nuclear bully on the playground,” says Heather Williams, a nuclear weapons experts at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

“Nonetheless it is Putin who is leading the way in threatening to break a taboo that has held for 77 years. What has not changed is that any nuclear use is a game changer and has strategic consequences,” she adds. “That is the reality the U.S. and NATO and the West have to continue to message to Putin and anyone else,” such as North Korea and Iran.

The creeping normalization of the use of low-yield or so-called tactical nuclear weapons – even if still only rhetorical – results from a number of factors, nuclear arms experts say. They include nuclear superpowers’ retreat from landmark arms control treaties and nuclear diplomacy, the unchecked proliferation of nukes in North Korea, and a shift among some military planners toward thinking of tactical nuclear explosives as a shock weapon useful to an “escalate to de-escalate” strategy.

Tactical nuclear weapons are smaller devices that can be fitted on shorter-range missiles, or even fired from the back of a pickup truck, deployed to annihilate an advancing military unit, for example, or destroy a few city blocks (rather than entire cities, targets for strategic nuclear weapons). Such weapons would still entail the threat of drifting radioactive clouds and long-term environmental impacts.

Another reason that Mr. Putin is threatening to use nuclear weapons may simply be that the Ukraine war has put on display the Russian military’s failures in conducting conventional warfare and its lack of high-tech, state-of-the-art weaponry, some say.

“When you are Russia, or for that matter when you are North Korea, your ability to fight the new generation of warfare … does not compare to South Korea, the U.S., or NATO,” says Henry Sokolski, executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center in Arlington, Virginia.

“And so what do you do? You jump to what you can do, which is to threaten using nuclear weaponry to achieve your objectives,” he says.

From battlefield nuke to mushroom cloud?

That would take the world into unknown territory, and new ways of using nuclear weapons. For decades, a hallmark of major powers’ nuclear policy has been deterrence. Now, Mr. Putin is using nukes as a tool of “coercion” to prompt desired responses from others, says Dr. Cooper, whose most recent book is “Arms Control for the Third Nuclear Age.”

The Russian president, he says, is warning the West that although “right now I’m sticking to lower-level stuff in Ukraine … you’d better not try to stop me or this will go to a nuclear level.”

“He’s betting he can backstop his conventional [warfare] problems in Ukraine with the nuclear threat, and he may be right,” Dr. Cooper adds. “We’re clearly in uncharted waters where our deterrence capabilities are significantly challenged.”

If Mr. Putin’s nuclear gambit were to succeed, a “normalization” of smaller tactical nuclear weapons would be “probable,” Dr. Cooper says, and could lead to nuclear proliferation worldwide.

That would be an alarming jolt after three decades of post-Cold War complacency encouraged by declining fears that big-power nuclear confrontation could subject the world to a fearsome “nuclear winter.”

“Nuclear weapons never went away; the public just forgot about them,” says Dr. Williams. “And then in the past we associated the nuclear threat with the big mushroom cloud and the devastating bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What Putin is talking about,” she adds, “are lower-yield tactical weapons that would likely be used on the battlefield.”

Even so, she says, the world needs to understand that their use would very likely entail the kind of broader “strategic consequences” that could lead to that mushroom cloud.

Patterns

When leaders don’t listen: Lessons from Liz Truss’ rise and fall

Leaders so sure of themselves that they do not listen to opposing views are shirking their responsibility to govern wisely, whether they be in London, Washington, Moscow, or Beijing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Just six weeks into her term as British prime minister, Liz Truss is struggling to keep her job not so much because of what she has done, as because of what she has not done.

Her plan to cut taxes for business and the wealthy was radical; the lack of any indication of how to pay for the cuts was daring. But her failure to listen to criticism or caution was fatal. From her first day in office she shut out or shrugged off doubters, denying herself a valuable corrective tool: a sounding board.

She has paid a harsh price. On Monday, in the face of market turmoil, her new finance minister canceled almost all the tax cuts she had wanted.

When you are a political leader, cutting yourself off from opinions other than your own has real-world effects everywhere. Former U.S. President Donald Trump ignored expert warnings about COVID-19. Russian President Vladimir Putin got his military into trouble in Ukraine by refusing to listen to invasion skeptics. Chinese leader Xi Jinping will hear no criticism of his bid to eliminate COVID-19, subjecting hundreds of millions of Chinese to lockdown.

There is no room for diverse opinions in an echo chamber, whether in London, Moscow, or Beijing.

When leaders don’t listen: Lessons from Liz Truss’ rise and fall

Even by the tumultuous standards of recent British politics – with three prime ministers in as many years – the rise and fall of the latest leader, Liz Truss, has been extraordinary.

It has been dizzyingly quick. It has damaged not just her reputation, but Britain’s economy.

It has also been almost entirely self-inflicted – which is why it carries important implications for Britain and other democracies such as the United States as well as autocracies like Russia and China.

That’s because the main reason Ms. Truss now finds herself scrambling to keep her job isn’t so much because of what she has done: her “supply-side” package of tax cuts and new spending without clear explanation of how to pay for it.

It’s because of something she hasn’t done: listen. More specifically, listen to voices of criticism or caution before launching her plan.

From the moment she entered Downing Street just six weeks ago, she has shut doubters out or shrugged them off. And that has denied her an invaluable corrective tool for anyone in government, especially at the top – a sounding board.

Her new finance minister’s wholesale abandonment on Monday of Ms. Truss’ original plan suggests she has now learned that lesson, though a growing number of her own Conservative Party colleagues are suggesting she has been too damaged politically to keep her job for much longer.

Monday’s unprecedentedly comprehensive U-turn was a culmination of events that started last Friday, when the prime minister fired her original finance minister, Kwasi Kwarteng. Now, she has had to sign on to a diametrically different approach by his successor, the more centrist veteran cabinet minister Jeremy Hunt.

Mr. Hunt announced he was canceling almost all the tax cuts. He was also time-limiting a multibillion-pound government support package to help people pay their rising energy bills, which Ms. Truss had vowed would last for two years. And he warned of budget cuts to avoid major new government borrowing.

His message was aimed at the financial markets. Their thumbs-down on the Truss plan had driven up interest rates, not just for the government but millions of British mortgage holders, while dragging down the value of the British pound.

The initial market response to Mr. Hunt’s reversal was the equivalent of a giant sigh of relief. Interest rates on government borrowing eased, and the pound began heading back upward.

Yet the difference between his approach and Ms. Truss’ ran deeper than economic policy.

Fundamentally, it was about listening. Consulting. Subjecting decisions to the filter of voices belonging to those with different expertise and experience, and those affected by what was ultimately decided.

One of Mr. Kwarteng’s first moves in office had been to sack the top civil servant in Britain’s treasury department. Before announcing the policy package that he and Ms. Truss had designed, neither of them bothered with the traditional pre-budget consultation with the Bank of England, Britain’s equivalent of the Federal Reserve.

They also dispensed with an analysis by the independent Office of Budget Responsibility of what the new plan would cost, how it would be paid for, and how much additional borrowing it would require the British government to take on.

These short circuits meant their policy announcement struck markets as ill thought out and very possibly unsustainable – less a rigorously developed plan than a back-of-the-envelope draft.

There’s a profound irony in this for Ms. Truss. If she had listened to advice, she might well have been able to retain the core ideological thrust of her policy, yet time tax cuts and expenditures in such a way, and explain them with sufficient credibility, that markets would not be spooked.

The longer-term lesson, however, is that the core responsibility of any government – to protect and ideally improve the day-to-day lives of the governed – risks being undermined if leaders are cut off from policy opinions, experience, and expertise other than their own.

And not just in Britain.

Ms. Truss’ dismissal of civil servants and other analysts as mere “bean-counters” echoes an increasing trend among populist-minded leaders in Western democracies, characterizing all experts as tunnel-vision elitists, allegedly part of an unaccountable “deep state.”

That’s a political judgment, but with real-world policy effects. One example is the way in which former U.S. President Donald Trump shrugged off experts’ warnings during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, preferring to repeatedly play down its seriousness.

Neither are autocrats immune. Russian President Vladimir Putin rolled his tanks into Ukraine in the clear expectation of a fairly easy victory, ignoring skeptical voices. The result has been the battlefield morass in which his forces now find themselves.

In China, where leader Xi Jinping is being formally endorsed this week as the most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, the policy effects are also evident. There is no more striking example than the lockdowns, affecting hundreds of millions of people, through which he has been pursuing his goal of “zero COVID.”

Had Mr. Xi listened to experts outside his inner circle, he would surely have updated and modified his policy so as to minimize the disruption to people’s lives.

But in the evolving politics of China, where Mr. Xi has become recognized as the sole embodiment of all political, historical, and social wisdom, alternative voices have been facing a lockdown of their own.

There is no room for diverse opinions in an echo chamber, whether in London, Moscow, or Beijing.

How Xi Jinping is reshaping China, in five charts

Chinese leader Xi Jinping is expected to win a rare third term in this week’s 20th Communist Party Congress. Understanding how Mr. Xi has transformed China over the past decade can offer clues for what comes next.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Jacob Turcotte Staff

Over the past 10 years, China’s leader Xi Jinping has consolidated power to a degree not seen since Mao Zedong. His rule has brought major changes to China – from his sweeping anti-corruption and poverty alleviation campaigns to a huge military buildup and more assertive foreign policy.

He’s now poised to win another five-year term as the Communist Party holds a series of twice-a-decade political meetings that will formally install its top leadership.

Where is Mr. Xi expected to lead the country? In a lengthy report to the congress on Sunday, he outlined a blueprint for the coming years. The main takeaway, experts believe, is that Mr. Xi intends to stay the course – maintaining or intensifying his ambitious drive for China’s “great rejuvenation,” despite a slowing economy and the controversy some of his policies have generated at home and abroad.

Amid speculation among overseas experts that China’s power has peaked, “there is no indication the Chinese think that way,” says Oriana Skylar Mastro, a Center Fellow at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. “They think they have this trajectory – whether it be toward reunification [with Taiwan] or having a world-class military – and they are on track.”

How Xi Jinping is reshaping China, in five charts

Over the past 10 years, China’s leader Xi Jinping has consolidated power to a degree not seen since Mao Zedong. His rule has brought major changes to China – from his sweeping anti-corruption and poverty alleviation campaigns to a huge military buildup and more assertive foreign policy.

In coming days, Mr. Xi is widely expected to win a rare third term at the pinnacle of the Communist Party, as it holds a series of twice-a-decade political meetings that will formally install its top leadership, including the 25-member Politburo and elite, seven- to nine-member Politburo Standing Committee.

Where is Mr. Xi expected to lead the country next? In a lengthy report to the congress on Sunday, he outlined what the party-run media described as a “blueprint” for the coming five years. The main takeaway, experts believe, is that Mr. Xi intends to stay the course – maintaining or intensifying his ambitious drive for China’s “great rejuvenation,” despite a slowing economy and the controversy some of his policies have generated at home and abroad.

“What is telling [about Mr. Xi’s report] is that there was no reformulation of any of these major policies, in spite of some of the challenges the party has faced recently,” says Oriana Skylar Mastro, a Center Fellow at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. Despite speculation among overseas experts that China’s power has peaked, she says, “there is no indication the Chinese think that way. They think they have this trajectory – whether it be toward reunification [with Taiwan] or having a world class military – and they are on track.”

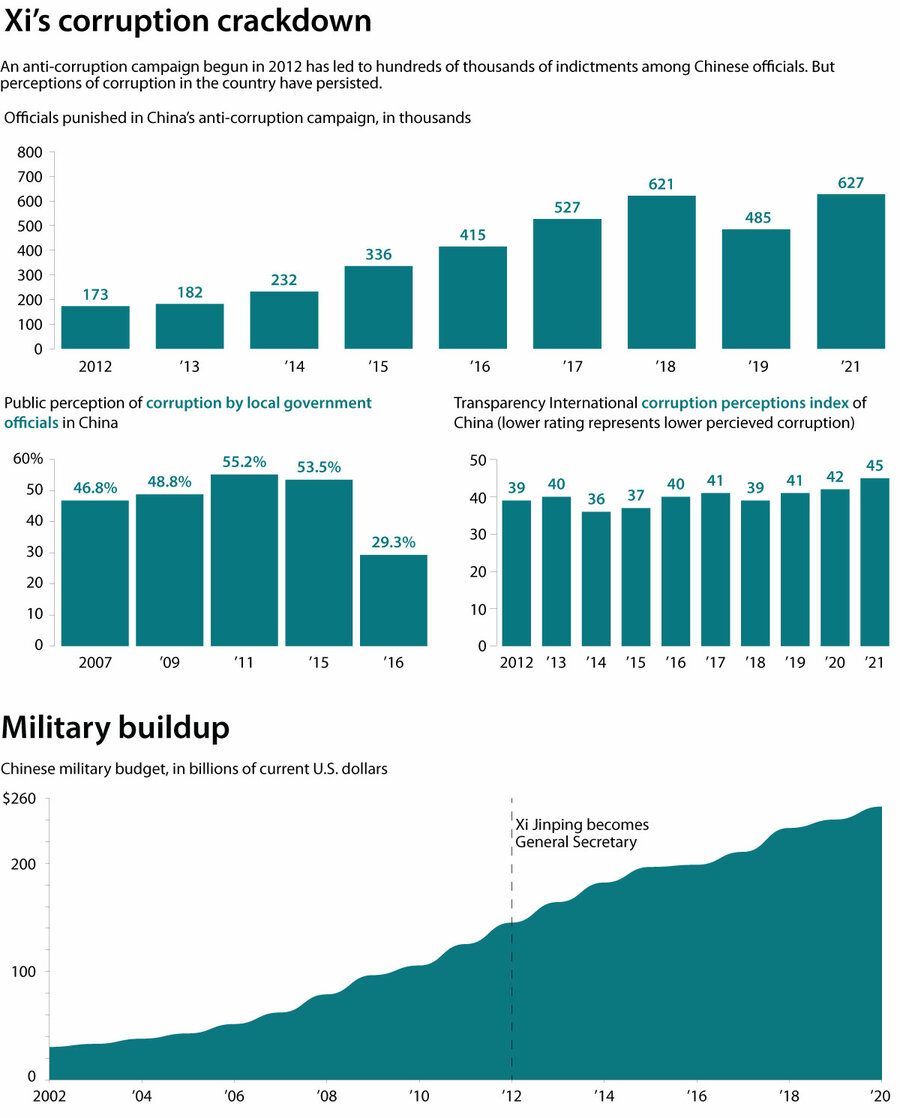

Corruption crackdown

Inside China, one of Mr. Xi’s signature policies has been his no-holds-barred sacking of Communist Party, government, and military officials – including senior party officials and People’s Liberation Army generals – for corruption.

In the three decades before Mr. Xi took power in 2012, China’s market-oriented economic reforms unfolded without a corresponding increase in political accountability or transparency, giving rise to an explosion of corruption. To Mr. Xi, dishonest and greedy officials posed a major obstacle to his bid to strengthen party rule, which he considers a prerequisite for China’s progress. He has taken a top-down approach to demanding greater “discipline” among cadres, investigating millions in the past decade.

Overall, the policy has been popular domestically, although Mr. Xi has also used the anti-graft push to eliminate political rivals, promote allies, and consolidate power in his own hands. And he is far from finished.

Speaking Sunday on a stage draped with bright red curtains framing a huge gold hammer and sickle in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, Mr. Xi told nearly 2,300 party delegates that corruption remains “a cancer to the vitality and ability of the Party.” Indeed, some experts say Mr. Xi has created so many political enemies that a continuous purge of the ruling elite is likely.

CGTN, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Transparency International

Income inequality and economic growth

China has made big strides in alleviating dire poverty under Mr. Xi, raising the incomes of millions of people above the country’s official poverty line. Mr. Xi, who declared extreme poverty eliminated in China in 2020, on Sunday hailed this as a “historic feat.” The policy has won Mr. Xi high popularity among Chinese in poor, rural areas.

Nevertheless, income inequality has surged during China’s economic boom, and as of 2020, 600 million Chinese still had monthly incomes of about 1,000 yuan ($140). Mr. Xi is targeting this gap between China’s haves and have-nots with a policy of “common prosperity,” a major focus for his next five years.

“We will promote equality of opportunity, increase the incomes of low-income earners, and expand the size of the middle-income group,” Mr. Xi said.

Chinese and foreign entrepreneurs worry, however, that Mr. Xi’s efforts to tackle inequality have involved sudden, somewhat clumsy, regulatory measures such as his crackdown last year on China’s most successful high-tech companies, which lost hundreds of billions in value virtually overnight.

Mr. Xi has also favored China’s state-run economy over the private sector and ordered a policy of frequent COVID-19 lockdowns – both serious drags on economic growth.

Peterson Institute for International Economics, Center for Strategic & International Studies

Military spending and national security

China’s military budget expanded to $252 billion in 2020, second only to that of the United States, as the country pursues a significant modernization and upgrading of its armed forces.

On Sunday, Mr. Xi pledged to accelerate his goal of building China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a “world-class” force by 2027, the 100th anniversary of the PLA.

China “will intensify troop training and enhance combat preparedness across the board” while also building “a strong system of strategic deterrent forces,” he said, in what the state-run media says is a reference to strategic nuclear weapons. “We will work faster to modernize military theory, personnel, and weapons,” he said.

The PLA’s mission, Mr. Xi said, is to safeguard China’s “core interests,” including its broad territorial claims over the South China Sea and Taiwan.

Over the past 10 years, Mr. Xi has stepped up pressure to unify mainland China with the self-governing island of Taiwan. On Sunday, he pledged in forceful tones that “complete reunification of our country must be realized, and it can, without doubt, be realized!” – triggering enthusiastic applause from the party delegates.

While seeking peaceful reunification, Beijing “will never promise to renounce the use of force,” he said, a warning that was directed at “interference by outside forces and the few separatists seeking ‘Taiwan independence.’”

But as China has stepped up pressure on Taiwan, with escalated air force incursions and major military exercises around the island, opinion polls in Taiwan show public sentiment has cooled on the idea of unification. This is in part because of the imposition of a draconian national security law on Hong Kong in 2020, which was viewed as undermining its autonomy promised under the “one country, two systems” formula, which Beijing also advocates for Taiwan.

World Bank

Foreign Affairs

China’s foreign policy under Mr. Xi has had mixed results.

On one hand, China continues to advance its influence and standing in the Global South. This is in part due to Mr. Xi’s massive “belt and road” investment push, which since 2014 has helped to fill a large infrastructure gap in developing nations. Mr. Xi has also closed ranks with other authoritarian states, in particular forging a close, “no-limits” alliance with Russia.

World Bank

Yet Mr. Xi’s more aggressive regional and foreign policy – and his unleashing of acrimonious “wolf warrior” diplomacy – has contributed to a deterioration of relations between Beijing and developed countries in Asia and the West, above all the U.S.

In his report, Mr. Xi railed against foreign interference, bullying, and hegemony, suggesting he may double down on his combative diplomatic approach with some countries, experts say.

“Xi has been very clear since 2013 that his tenure as leader would be about regaining China’s status on the international stage and resolving other core interests, mainly territorial issues, even at a cost,” says Dr. Mastro from Stanford. “We will probably continue to see, in their minds progress, and in our minds disruptions and harassment, in all these areas,” she says. “That is going to be pretty much guaranteed for the next five years.”

Pew Research Center

CGTN, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Transparency International, World Bank

Evacuation orders, safety, and Florida’s hurricane culture

Could more have been done to save lives as Hurricane Ian struck Florida? The answer hinges partly on government evacuation orders, but also on individuals’ ability and willingness to heed those orders.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Florida is one of the most hurricane-prone areas in the country, and hence has its own hurricane culture. People here stick “Hurricane Life” stickers to their windshields. Many have generators and storm-hardened homes and stores of essentials. When an actual storm comes – even one as dangerous as Ian – some don’t evacuate.

Or they don’t know to leave in time. Lee County, which contains some of the hardest-hit areas, has already come under scrutiny for mandating evacuations just a day before the storm – after it abruptly shifted southward. But evacuating an area is a shared responsibility. Local government needs to communicate the risks. Only residents, though, can decide to leave.

Warming oceans and air are predicted to make storms more destructive and less predictable, so each responsibility is becoming more important. Governments can better assess how locals decide to stay or go, says Rebecca Morss, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Meanwhile, locals need to recalculate the danger of hurricanes in a warming world.

“The challenge,” Dr. Morss says, “is understanding that every storm can be different.”

Evacuation orders, safety, and Florida’s hurricane culture

Christina Morris is an island person. She’s lived in Florida since 1993, and in a two-story house on the south end of Pine Island – off the coast of Fort Myers – for the past 2 1/2 years.

And island people know their hurricanes, she says. She was on Fort Myers beach during Hurricane Charley, a Category 4 storm 18 years ago, and she saw “Wizard of Oz stuff.” At one point, a manatee washed ashore. People ran to the beach, carried it on a piece of driftwood like a stretcher, and brought it back to the ocean.

So ahead of Hurricane Ian, with her mother visiting, with her six rescue animals, and with a sturdy two-story house, Ms. Morris decided to stay. Then the storm hit.

Ms. Morris spent hours sheltering in the upstairs bedroom with her mother, two dogs, and four cats. The window burst, and she had to shove her back against the door so it wouldn’t fly open. Charley, she says, was a “cakewalk compared to this.”

But she doesn’t think this will change how her area approaches its next hurricane, whenever it comes. “People here are just who they are,” says Ms. Morris. “We just survived a Cat 5. Do you think we’re going anywhere?”

Florida is one of the most hurricane-prone areas in the country, and hence has its own hurricane culture. People here stick “Hurricane Life” stickers to their windshields. Many have generators and storm-hardened homes and stores of essentials ahead of hurricane season. When an actual storm comes – even one as dangerous as Ian – some don’t evacuate.

Or they don’t know to leave in time. Lee County, which contains Pine Island and some of the hardest-hit areas, has already come under scrutiny for mandating evacuations just a day before the storm – after it abruptly shifted southward. But evacuating an area is a shared responsibility. Local government needs to communicate the risks. Only residents, though, can decide to leave.

Warming oceans and air are predicted to make storms more destructive and less predictable, so each responsibility is becoming more important. Governments can better assess how locals decide to stay or go, says Rebecca Morss, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Meanwhile, locals need to recalculate the danger of hurricanes in a warming world.

“Florida does experience hurricanes a lot of years,” says Dr. Morss, who specializes in weather-related risk communication. “And so the challenge is understanding that every storm can be different.”

A difficult place for evacuations

In the days before landfall, Hurricane Ian initially looked on track to hit the Tampa Bay area, one of the state’s population centers. The National Hurricane Center’s “cone of uncertainty,” a widely misunderstood model of where the center of the storm could arrive, had most of Lee county on the outer edge by even Monday. A day later, after the storm shifted southward, the area issued mandatory evacuation orders for the areas most at risk.

The county’s coast includes a set of highly populated barrier islands, vulnerable to storm surge – the top cause of fatalities during a hurricane. The population and road system also make it “the hardest place in the country to evacuate in a disaster,” according to a 2015 county document on evacuations.

More than 58 people so far are known to have died in Lee County due to the hurricane, more than half of the total deaths in the state.

Despite county policies on evacuating earlier when there’s a risk of major storm surge, the order didn’t necessarily arrive too late, says John Renne, director of the Center for Urban and Environmental Studies at Florida Atlantic University. “It seems like the call they made was reasonable,” he says.

Had Ian continued north toward Tampa, he says, having more cars on the road due to evacuations elsewhere could have clogged the highways. Regardless, local governments can only create evacuation plans, arrange shelters, and communicate risks to the public. They can’t force citizens to leave. That means people are ultimately responsible for their own safety, says Professor Renne, who researched evacuation decisions before Hurricane Katrina while working at the University of New Orleans.

“People need to have a plan,” he says. “They shouldn’t necessarily rely on the government for help.”

But an enormous number of variables affect a decision to stay or go, says Dr. Morss. Often people don’t have a plan equal to a hurricane’s risk. Pets, cars, personality types, homes, hotels, hurricane scale, forecasts, evacuation orders – these can all affect a household’s decision, she says. People’s past hurricane experiences also weigh into the choice, and in an area like Florida almost everyone has past hurricane experience.

Most people in the area evacuated to somewhere relatively safe during Ian. Still, some like Ms. Morris, standing outside her house with two dogs tying their leashes in knots, say surviving hurricanes is part of the local identity.

“People here are just who they are,” she says. “They’re old school.”

One couple’s decision to flee

In the past few weeks Fort Myers Beach, about 30 miles away from Pine Island, has come to look like a tourist landfill. Construction vehicles have piled up mounds of debris. The island reeks of seawater.

Michele Bruns and her husband, who have lived there for 10 years, came home for the first time in two weeks, Oct. 10 – and spent the day gutting their beachfront condo, nine floors up, so the upholstery and remaining food didn’t start to mold.

They left the Tuesday before the storm, after following the weather forecasts and deciding their safety was more important than their stuff. “You’ve got to be smart about it,” she says. “Our lives are the most important thing, and everything else can be replaced.” Locals had enough time to evacuate, she says, but her husband understands why some – including a few acquaintances – didn’t. Forecasts of deadly storm surge have been wrong so many times before, he says. Some people just stop listening.

And evacuating is difficult. Ms. Bruns and her husband couldn’t find a hotel anywhere between Fort Myers and Miami. Eventually they booked a room in Fort Lauderdale, two hours away. The beach didn’t reopen for two weeks. They’re now moving everything into a nearby apartment, which they’ve rented for a year.

“We’re staying here, absolutely,” she says. “We love this place. The hurricane isn’t going to make us move.”

A quarter mile down a sandy traffic jam on Estero Boulevard, Louis Monaco sits under a tent wearing a Chicago Cubs hat and gym shorts. He’s eating a free meal from the World Central Kitchen truck, which has been there for a number of days. Beside it is the mobile facility where he does his laundry and the trailer where he showers.

Mr. Monaco has lived in Fort Myers Beach almost since he graduated college 30 years ago. His wife left for their son’s home, a few miles inland, the day before the storm. For most people, be says, the smart thing was to leave. But unless Ian became a Category 5, says Mr. Monaco, he would stay.

“The captain don’t leave his ship,” he says.

So he sheltered on the second floor of his mid-island home. Again and again, he went downstairs to stack things on top of his truck in order to keep them dry. Eventually, that too was underwater.

“To actually see structures and houses come floating down the street – it was a little nerve-wracking,” he says. At times, he wondered whether he would make it. Looking back he doesn’t regret his decision. He’s thankful he saved pictures of his sons.

Mr. Monaco has spent the past few weeks ripping out wallboard on the bottom floor of his house and cleaning his yard – which the sheriff told him was the best looking now on the island. The town will take years to rebuild, and he’s starting now, praying it’s the last time.

“I think in my lifetime I’m not going to see something like this again – I hope,” says Mr. Monaco.

Make them laugh: Dalit comics challenge caste, one joke at a time

Comedy can be a tool to talk about the taboo. In India, a growing number of Dalit stand-ups are opening up about caste and demanding equality – onstage and off.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Qadri Inzamam Contributor

Manjeet Sarkar is one of a small but growing number of Dalit stand-ups breaking into India’s comedy scene, which has long been dominated by comics from the upper echelons of the ancient Hindu caste system. Although caste-based discrimination has been outlawed in modern India, anti-Dalit violence and stigma prevail across the country, and experts say the entertainment industry is no different.

But recently, Dalit comics have gone viral online for poking fun at caste-related issues, and some comedy shows now market all-Dalit lineups. Some comics have built careers on using humor to unpack firsthand experiences with casteism, including Mr. Sarkar, who cites Black comedians in the United States as major inspiration.

Comedians say talking about caste onstage has not only been personally empowering, but also offers a rare opportunity to challenge largely upper-caste audiences to think deeply about issues of caste.

“When they laugh at my jokes, they are in a dilemma whether they should laugh or feel guilty,” says Mr. Sarkar, adding that comedy provides a degree of protection.

“I can convey my thoughts without thinking twice whether I will be mob-lynched or beaten up,” he says. “Being on the stage gives me a sense of liberty and equality.”

Make them laugh: Dalit comics challenge caste, one joke at a time

Late one recent Saturday night, stand-up comedian Manjeet Sarkar walked up to a makeshift podium inside a jampacked cafe in the posh city of Bengaluru. Mr. Sarkar is a Dalit, a community regarded as “untouchable” by upper-caste Hindus. The audience welcomes him with loud applause, and once everyone settles in, Mr. Sarkar cracks his first one-liner: “If anyone does not laugh at my jokes, I touch them.”

The crowd loves it.

The quip takes aim at the Hindu caste system, a rigid, centuries-old hierarchy that places Dalits like him on the lowest possible tier, below Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. Old laws called for their physical and social segregation, and although the practice of “untouchability” has been outlawed in modern India, anti-Dalit violence and stigma prevail across the country.

For another half-hour, Mr. Sarkar makes a largely upper-caste audience laugh at jokes about the discrimination Dalits face and the classism that exists in elite Indian circles.

He is one of a small but growing number of Dalit comedians breaking into India’s Brahmin-dominated comedy scene. Onstage, they’re finding that examining caste through humor not only makes for better comedy, but is also personally empowering.

“I can convey my thoughts without thinking twice whether I will be mob-lynched or beaten up by someone,” says Mr. Sarkar. “Being on the stage gives me a sense of liberty and equality.”

Caste can be funny

The culture of independent stand-up comedy emerged in India in the early 2010s, fueled by the rise of YouTube and influenced by comedians in Britain, Canada, and the United States. Back then, only upper-caste people could afford to work unpaid shows and open mics, and even nowadays, when there’s more money to be made, that’s who dominates the comedy circuit.

Madhavi Shivaprasad, an independent researcher based in Bengaluru who has also published a paper on caste and stand-up comedy in India, says that like other art forms, Indian stand-up has historically been very exclusivist. While many upper-caste comedians identify as feminists and progressive, they “do not acknowledge the caste barrier they are responsible for putting up” in the industry, she says.

In her paper, Ms. Shivaprasad argues that comedians have a special responsibility to challenge castism, writing that “danger lies in the possibility that discriminatory attitudes get sanctioned and reinforced, particularly through the guise of humour, where ‘nothing is serious anyway.’”

Until recently, few comedians in India have been willing to do that. But when Mr. Sarkar looked overseas, he saw comic legends like Kevin Hart, Jordan Peele, Bernie Mac, and Eddie Murphy criticizing racism.

In America, Black comedians “talk about how their people faced generational oppression. That intrigued me,” says Mr. Sarkar, who’s been performing stand-up for five years now. “I realized comedy is an art form where you can talk about things which are taboo.”

Mr. Sarkar’s jokes are rooted in his lived experiences as a Dalit growing up in a tribal Naxalite area in eastern India. During the show, Mr. Sarkar talks about how untouchability was normalized in his home village. He recalls how in his childhood he was yelled at by an upper-caste woman for drinking from a public hand pump. The woman later washed the hand pump with Gangajal – the sacred water of the Ganges – to purify it.

“Then I touched the Gangajal itself, and she had to purify the Gangajal with Gangajal,” Mr. Sarkar tells the audience, eliciting another burst of laughter.

People come up to Mr. Sarkar after most shows and ask him to “tone down the anti-caste jokes,” but not at this one.

After Mr. Sarkar leaves the stage, audience member Pranjal Das comments that he and his sibling didn’t know Mr. Sarkar was a Dalit going into the show, but they enjoyed his set nonetheless. “I was shocked to hear a few things he said,” Mr. Das adds.

That’s one of Mr. Sarkar’s favorite parts of this job – shocking the audience members out of their comfort zone, forcing them to think about caste from a new perspective.

“In most cities, the audiences are privileged and upper caste. … When they laugh at my jokes, they are in a dilemma whether they should laugh or feel guilty,” Mr. Sarkar says.

Finding authenticity onstage

Not every Dalit comic leans into their caste identity. For some, the first instinct is to veer away from that topic.

Ankur Tangade, a stand-up comedian and social activist who travels frequently to perform around India, has only started integrating her caste identity into her comedy this year.

She used to stick to subjects that were familiar to upper-caste audiences. “I thought connecting to the audience was important, and being a Dalit and having such content would not be relatable,” she says.

But recently, her perspective shifted. She realized she could make a better mark for herself and create more useful comedy, if she let her audience get to know her. Ms. Tangade gradually started talking about being queer and a Dalit in her shows, and now she frequently pulls from her life experiences, like when a former partner had “backed out” once he learned she was a Dalit. “His parents were OK with anyone but a Muslim or Dalit girl,” she says with a chuckle.

Ms. Tangade says she’s trying to raise awareness about discrimination, and hopes her visibility as a Dalit comic will help pave the way for more equality in the entertainment industry and beyond. “We are here to tell people that you cannot ignore us and that we are equal,” she says. “Everyone talks about their own life, but no one talks about minorities.”

The growing number of Dalit comics gives Ms. Shivaprasad, the researcher, hope for India’s comedy scene. Dalit comics have gone viral online for poking fun at caste-related issues, and some comedy shows now market all-Dalit lineups. “There are people and groups that do anti-caste and feminist comedy,” she says, “which is different than the way mainstream comedians perform.”

Still, having more openly Dalit comedians doesn’t always translate to more opportunities.

Ms. Tangade recalls an instance when a production house she had worked for chose to sign an upper-caste performer despite having a dozen Dalit artists to pick from. Only later did she learn that all the people in positions of power at that company were upper caste themselves.

“People want to help their own,” she says. “Dalits don’t have anyone to pull them up. As a Dalit, you have to carve your way up.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The force of peaceful tactics

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

At a time of global concern about democracy, violent crackdowns against protesters in Iran and Myanmar illustrate the difficulty of challenging authoritarian rule. Yet in two countries, Sudan and Venezuela, the tactics of pro-democracy activists may be showing how peaceful transitions are not just possible but perhaps inevitable.

Both countries are being nudged by regional and Western leaders toward talks to restore inclusive and accountable government bound by the rule of law. That goal, observers say, may rest on a characteristic the two countries share – a commitment by activists to nonviolence.

“The way to change society is to change ideas,” said Giannina Raffo, a Venezuelan activist who helps develop websites and apps for peaceful campaigns by civil society groups.

Autocracy may be having a global moment, but the peoples of Sudan and Venezuela are showing that peaceful struggle against a violent ruler can help set a precedent for rule by law, freedom, and equality. The process itself reflects the ultimate goal.

The force of peaceful tactics

At a time of global concern about democracy, violent crackdowns against protesters in Iran and Myanmar illustrate the difficulty of challenging authoritarian rule. Yet in two countries, Sudan and Venezuela, the tactics of pro-democracy activists may be showing how peaceful transitions are not just possible but perhaps inevitable.

Both countries are being nudged by regional and Western leaders toward talks to restore inclusive and accountable government bound by the rule of law. That goal, observers say, may rest on a characteristic the two countries share – a commitment by activists to nonviolence. As the United States Institute of Peace noted earlier this month, “an asset that can help Sudan build the more responsive governance it needs is the country’s remarkably vibrant, deeply rooted tradition of nonviolent civic action.”

Sudan and Venezuela face similar crises. They are ruled by disputed governments that have overseen acute economic and humanitarian crises. In Sudan, 8.3 million people face severe hunger, according to the World Food Program. In Venezuela, 95% of the population lives in extreme poverty, and nearly 7 million have fled since 2014, according to the United Nations. In both countries, security forces have responded to public protests with violence and detentions.

The international community had hoped that isolating the two regimes – one a military junta that seized power in a coup last year, the other an autocratic regime that 50 countries regard as illegitimate – would compel them to change. There is now growing recognition that that strategy, which includes targeted sanctions, has not worked. And amid changing global energy security conditions, the Biden administration and others see a benefit in bringing the two oil-producing nations back in from the cold. Both have lately signaled an openness to talks.

That receptiveness, however, may be motivated less by the dangling of international carrots than by a recognition that intimidation has not quelled popular aspirations for a just society. In Sudan, for example, the junta’s tanks are up against a concept of nonviolent resistance called silmiya, which the Sudanese filmmaker Mohamed K described in a recent study as “the atmosphere of love.”

That ethos is one reason why nonviolent campaigns are “10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period” compared with countries that have violent anti-government campaigns, according to Harvard University professor Erica Chenoweth. Nonviolent civic protests, she noted in an interview with The Harvard Gazette, achieve three important goals. They unite society around shared values, empower moderates, and deprive repressive regimes of justifying violence against their own people.

“The way to change society is to change ideas,” said Giannina Raffo, a Venezuelan activist who helps develop websites and apps for peaceful campaigns by civil society groups. One key concept involves defending the “freedom to express ourselves without fear and to be able to criticize and combat everything we consider ... antidemocratic,” wrote Antonio Perez Esclarin, a professor at Simón Rodríguez National Experimental University in Caracas, on his blog.

Autocracy may be having a global moment, but the peoples of Sudan and Venezuela are showing that peaceful struggle against a violent ruler can help set a precedent for rule by law, freedom, and equality. The process itself reflects the ultimate goal.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Where do we look for stability?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Sometimes stability – in our lives, or in the world at large – can seem out of reach. But getting to know God as unchanging good empowers us to feel more fully God’s stabilizing presence.

Where do we look for stability?

Whether in our own family or within the wider community, changes can occur that put a familiar stabilizing influence out of reach. The loss of a loved relative or a respected leader, for instance, can cause us to ask if their unique impact will be lost too.

Over many decades, I’ve been learning how true it is that the qualities we value in others have a source that is never lost: God. Therefore, in changing times we can look for continuity in a deepening grasp of our relation to God, our oneness with all that God is, including spiritual Life, Truth, and Love.

Christian Science teaches the value of looking Spiritward in this way to discern an underlying consistency that is not at the mercy of the ebb and flow of human experience. This Science reveals the truth that God is Spirit, infinite and unchanging good, and that this is our only life.

Understanding this has a practical impact, calming our anxieties and purifying our thoughts and actions. Words from the book of Isaiah paint a picture of such transformation: “Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain” (40:4).

The writer was referring to a bigger issue than individual temperament, foreseeing and foretelling the life of John the Baptist, who would prepare people for the coming of Christ Jesus. But in our lives, too, we can pave the way for the coming of Christ – not as a previously absent personal Messiah, but as the ever-present spiritual idea of Truth, forever discoverable in our consciousness.

The timeless spiritual idea of God that enabled Jesus to love with such healing effect is revealed in the Bible and the Christian Science textbook – Mary Baker Eddy’s “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.” The healing ideas in these books offer a clear understanding of God and our relation to God, and through this understanding we can glimpse the life of Life, feel the truth of Truth, and better see how to express the love of Love. This enables us to perceive and experience God’s stabilizing presence and power in practice.

Opening our thought to this divine influence lifts us to see ourselves and others in spiritual terms. While we always appreciate the expression of good shining through the example of others, our security is in seeing our own and everyone’s changeless oneness with God. Understanding this unveils fresh opportunities to do good ourselves and brings to light inspired and practical answers to the challenges we face as individuals and as a society. So, we can open our heart to the saving action of Truth identified by Mrs. Eddy. A poem of hers says,

And o’er earth’s troubled, angry sea

I see Christ walk,

And come to me, and tenderly,

Divinely talk.

Change is essential in a world brimming over with the misleading conviction that matter is the foundation and substance of being. And Christ is at hand to empower our adherence to Truth as matter’s limitations are exposed and matter is found to have no intelligence, substance, or reality. The upshot of listening for, hearing, and heeding Christ’s message is increased recognition that instability, like all discord, is actually a material misperception of Spirit, which is all-harmonious.

Mrs. Eddy’s poem continues:

Thus Truth engrounds me on the rock,

Upon Life’s shore,

’Gainst which the winds and waves can shock,

Oh, nevermore!

(“Christ My Refuge,” “Poems,” p. 12)

This Truth is always true. Jesus once commented on two widely known incidents in his day, a fatal accident and a murderous abuse of power (see Luke 13:1-5). Both took many lives. When asked about such destabilizing events, Jesus rebuked the tendency to speculate on material reasons for the tragedies. He highlighted a deeper need to see through the false belief in life’s supposedly mortal framework, which would include belief in random or criminal danger. In the reality of divine Life that Jesus exemplified and proved, there is only goodness, with no contrasting subjection to any such evil.

Jesus knew that the unfolding of God’s infinite goodness truly and provably excludes all else. That goodness continues unabated, whatever loss might loom large in our individual lives or the life of a nation. The enduring stability that Christ reveals remains intact: It is God’s infinitely just, eternally benign, and flawlessly wise presence, power, and love.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Oct. 17, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Reunited

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow for a report on how one community in southwest Nigeria, long neglected by local government, has come together to tackle the devastating effects of deforestation.