- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Protest anthem ‘Baraye’ captures Iranian people’s yearnings

April Austin

April Austin

How does a protest song become an anthem? For Iranians entering a fifth week of demonstrations against the government, the song “Baraye” captures pent-up longing, frustration, and sadness.

“Baraye” was composed by a young Iranian singer, Shervin Hajipour, after the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini. Using tweets from protesters, Mr. Hajipour stitched together lyrics that unfold the hopes and dreams of the Iranian people – in their own words:

“For my sister, your sister, our sisters

For changing rusted minds.”

The song also reflects exhaustion with theocratic rule, gender inequality, economic sanctions, and lack of opportunity. The video of Mr. Hajipour singing “Baraye” went viral, racking up more than 40 million views on Instagram before authorities made him take it down. He was arrested Sept. 29 and briefly detained before being released on bail.

The message of “Baraye,” which means “for the sake of” in Farsi, is both particular and universal, says Christiane Karam, a professor at Berklee College of Music in Boston. She grew up in Lebanon during the civil war, and found refuge in her music. Now, at Berklee, she teaches a class in songwriting as social change.

“Music has that ability to cut through our defenses and go straight to our hearts,” she says in a phone interview. “It brings us to a place where we’re reminded of our shared humanity.”

Mr. Hajipour is “speaking his own truth,” she says. “And this is why it’s touching us so deeply. This is at the heart of any powerful and impactful song.”

Professor Karam isn’t alone in her admiration. “Baraye” garnered over 85% of the 127,000 submissions for a new Grammy special merit award, best song for social change, as of Oct. 13, according to the Recording Academy.

“This is how momentum is built,” she says. “A momentum for positive change and momentum where we all are reminded that we are all in this together.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With midterms looming, Democrats play defense on crime

Republicans running on crime is nothing new. But as many Democratic-run cities struggle with elevated levels of violence and disorder, the GOP message may be resonating.

Crime is not the uppermost concern for voters right now, most of whom list the economy and inflation as the most important issues facing the country.

But with just weeks to go until Election Day, Republicans across the country are making violent crime – and the charge that Democrats are unable or unwilling to curb it – a central focus. And recent shifts in the polls in several key races suggest the attacks may be moving the needle.

Many large Democratic-controlled cities in swing states have struggled with higher levels of crime and homelessness since the pandemic, and Democratic candidates are being forced to distance themselves from previously held positions on things like bail reform or the controversial push to “defund the police.”

In Pennsylvania, where the number of Philadelphia homicides is already close to surpassing last year’s record high, Mehmet Oz has spent millions on ads calling his Democratic opponent John Fetterman “soft on crime.” The Republican’s campaign has particularly focused on Mr. Fetterman’s role securing releases for some convicted murderers.

Mr. Fetterman addressed the attacks directly at a recent rally in critical Bucks County. “[Dr. Oz is] lying about my record on crime. I’m running on my record on crime,” he said.

With midterms looming, Democrats play defense on crime

Heading into Senate candidate John Fetterman’s rally on a recent Sunday, Democratic voter Kate Sommerer waves dismissively at the protesters across the street. The group, some wearing orange prison jumpsuits, are waving posters that read: “Violent Criminals 4 Fetterman” and “Felons 4 Fetterman.”

“It’s because they don’t have anything else to go on,” says Ms. Sommerer, rolling her eyes. “I think [the race] is going to be tighter than what we initially thought,” she adds. “But I still think John’s going to pull it off.”

In the final stretch before Election Day, the race for Pennsylvania’s open Senate seat has tightened considerably, with the independent Cook Political Report recently moving it back to “tossup” status. Mr. Fetterman, the hoodie-wearing lieutenant governor who previously held a double-digit lead in the polls, was forced to limit his public schedule throughout the summer while recovering from a stroke. And lately, he has been thrown on the defensive over one issue in particular: crime.

It’s not just Pennsylvania. In contests across the country, Republicans are making violent crime – and charges that Democrats are unable or unwilling to curb it – a central focus of their campaigns.

In many ways, it’s an age-old political play – one that Democrats say often has racist undertones. Richard Nixon famously promised to restore “law and order” after the civil rights clashes of the 1960s. Two decades later, George H.W. Bush released his controversial Willie Horton ad about a Black inmate who committed a rape after being granted a weekend furlough by Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis. More recently, Donald Trump made urban crime a central focus of both his campaigns, frequently highlighting violent offenses by unauthorized immigrants among others.

Crime is not the uppermost concern for most voters right now. In the New York Times/Siena poll released this week, voters from both parties overwhelmingly listed the economy and inflation as the most important issues facing the country, while the percentage choosing crime as the top issue was in the low single digits.

Still, recent shifts in the polls in several key races suggest the GOP’s attacks could be helping to move the needle. Many large Democratic-controlled cities in swing states have struggled with higher levels of crime and homelessness – as well as a general sense of disorder – since the pandemic. And several Democratic candidates are being forced to explain or distance themselves from previously held positions on things like bail reform or the controversial push to “defund the police.”

In Pennsylvania, where the number of Philadelphia homicides is already close to surpassing last year’s record high, Republican nominee Dr. Mehmet Oz has spent millions on ads calling Mr. Fetterman “soft on crime.” The Oz campaign has particularly focused on Mr. Fetterman’s role on the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, where he secured releases for many nonviolent offenders but also for some convicted murderers.

“Lieutenant Governor Fetterman has some outlandish views on crime and punishment, and he has not been shy about talking about them for many years. The ads you see running against him on crime are just clips of audio he’s said himself,” says Chris Nicholas, a GOP political consultant and former campaign manager for the late Sen. Arlen Specter. “Add that to the fact that violent crime in Pennsylvania is on the rise. ... You have the perfect storm for Republicans in this Senate race.”

A pattern from Wisconsin to Oregon

A similar dynamic is unfolding in the Wisconsin Senate race, where Democrat Mandela Barnes – also his state’s lieutenant governor – is now trailing incumbent Republican Sen. Ron Johnson, after holding slim leads in polls over the summer. As the homicide rate in Milwaukee continues to tick up, Republicans have been emphasizing Mr. Barnes’ past support for abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “defunding the police,” and eliminating cash bail.

Mr. Barnes has had to play defense. “I’ll make sure our police have the resources and training they need to keep our communities safe,” Mr. Barnes says to the camera while unpacking groceries in an ad titled “Truth.”

Even in deep-blue Oregon, polls show the Republican candidate for governor currently is leading amid a campaign focused largely on crime. Portland was the site of prolonged clashes between antifa, the radical left-wing groups, and law enforcement beginning in the summer of 2020. The city’s violent crime rate rose 38% last year, and homelessness and drug overdoses are up sharply.

In Pennsylvania, “Big John” Fetterman cuts a unique figure among Senate hopefuls with his Carhartt sweatshirts, goatee, and tattoos. The former mayor of Braddock, a small, mostly Black city outside Pittsburgh, he blends progressive positions on issues such as marijuana legalization and LGBTQ equality with more pragmatic stances on guns and hydraulic fracturing. Supporters hail him as a rare Democratic candidate with an Everyman persona who can appeal to both urban and suburban elites as well as working-class union members.

“He’s a good person. He was the mayor of a small town and seven people got murdered and he has them all tattooed up his arm. He’s passionate,” says Fetterman supporter Lisa Nastasiak. Mr. Fetterman’s right arm is in fact tattooed with nine dates memorializing residents lost to violence during his tenure as mayor. He frequently cites the fact that Braddock went for more than five years without a homicide due to gun violence while he was mayor.

But Mr. Fetterman’s past comments in favor of decriminalizing all drugs, support for sanctuary cities, and particularly his efforts to release convicted offenders from prison, have made him vulnerable to Republican attacks. In a review of three primetime Fox News programs during the month of September, Media Matters for America found Mr. Fetterman’s name was mentioned at least 120 times – more than triple the mentions of Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona, the second-most mentioned Democratic candidate.

Mr. Fetterman addressed the attacks in a 10-minute rally appearance, in front of roughly 1,000 voters in a park above the Delaware River in politically crucial Bucks County.

“We’re still standing,” he said, in his slower, post-stroke cadence. “We’re more than standing, we’re winning.” Mr. Fetterman raised $22 million in the third quarter, a new Pennsylvania record according to the campaign. And he is still leading Dr. Oz in the polls, albeit by much smaller margins.

Perhaps more important, in a late September Fox News poll, 65% of Democrats said they supported Mr. Fetterman “enthusiastically.” Just 38% of Republicans said the same about Dr. Oz, a Turkish American surgeon who rose to fame as a regular guest on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” in the early 2000s. A longtime New Jersey resident, Dr. Oz also starred in his own daily talk show, during which he gave health advice that’s since been criticized by many in the medical community.

The Oz campaign did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The suburban vote and abortion

As in most elections, the outcome in many close statewide races this year may hinge on the suburbs. While the violent crime in Philadelphia may not directly affect Bucks County’s small, suburban towns, that doesn’t mean the issue isn’t a potent one, says Bucks County Republican Committee Chair Pat Poprik.

“We’re law enforcement people here,” says Ms. Poprik. “The people of Bucks County feel it when they go into the city, and they don’t want it here.”

There’s some evidence Philadelphia’s rising crime rates have begun to concern not just Republicans but Democrats. In mid-September, both parties in the state legislature voted to hold Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s progressive district attorney, in contempt for failing to comply with a subpoena from a newly formed Select Committee on Restoring Law and Order. Republican lawmakers have been trying to impeach Mr. Krasner – who filed his own contempt motions against the Philadelphia Police Department last year – accusing him of failing to enforce the law.

Earlier in the summer, following the Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade and the right to an abortion, Democrats had begun to feel cautiously optimistic. Despite history showing the president’s party almost always loses seats in the first set of midterm elections, the sudden focus on abortion – which a majority of Americans believe should be legal – seemed to be energizing women voters, as state after state banned the procedure.

Still, some strategists warned against relying too heavily on it. “It’s a good issue,” Democratic strategist James Carville told The Associated Press. “But if you just sit there and they’re pummeling you on crime and pummeling you on the cost of living, you’ve got to be more aggressive than just yelling abortion every other word.”

At the Fetterman rally, the candidate’s wife, Gisele, reminds the crowd that her husband “understands that our basic rights, including abortion rights, are on the line.” Other Democratic candidates for statehouse races also mention abortion. Even Mr. Fetterman’s response to Dr. Oz’s crime attacks flows into an inevitable segue.

“Let me ask you: What has Dr. Oz ever known about crime, or fighting crime, living in a mansion in New Jersey? Oz might be a joke – but it’s really not funny because abortion rights are on the ballot right now,” says Mr. Fetterman to the cheering crowd.

“[Dr. Oz] spent his career lying about magic pills, and now he’s spending his entire campaign lying about my record on crime,” he says. “I’m running on my record on crime.”

The Explainer

Intervention in Haiti: Can the world respond without interfering?

Haiti’s government is asking for international military help to regain control from violent gangs that have immobilized the capital city, Port-au-Prince. Now world leaders – including Haiti’s – must weigh the consequences of intervention and its controversial history.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The Haitian government is calling for international military intervention to avoid a “major humanitarian crisis.” Armed gangs closed access to one of the country’s main fuel terminals, forcing gas stations to shutter and hindering essential services like banks and hospitals.

Does Haiti need intervention? What has gone wrong – and right – with the long history of international intervention there? And is there an international responsibility to intervene?

Haitians and veteran Haiti watchers tell the Monitor that lives are at stake in the turmoil. And even though the chaos has reached unprecedented levels, there’s still hesitancy by Haitians themselves to invite foreign powers in. Likewise, though the United States and Canada sent armored vehicles over the weekend, foreign powers are reluctant to get entangled, again, in what is already a fraught history of international interventions in Haiti, a nation that has been independent since enslaved people revolted in 1804.

“I can’t say that the government controls the situation in the country right now. If we have some kind of foreign intervention, maybe we can have some change quickly,” admits a Haitian government appointee who asked not to be named and believes that in the long run the country will still be left with the problems it has always had.

Intervention in Haiti: Can the world respond without interfering?

Even for a nation facing constant political turmoil and violence, chaos in Haiti has escalated to unprecedented levels since President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in July 2021. Armed gangs have immobilized the capital, Port-au-Prince, shutting down the already troubled economy and creating fear among citizens to even walk the streets.

The administration of Prime Minister Ariel Henry has issued a “distress” call for international military intervention to avoid a “major humanitarian crisis.” The United States and Canada responded over the weekend with a shipment of armored vehicles; and the United States and Mexico are preparing a United Nations resolution that would authorize an international mission to help improve security in Haiti. But the fraught history of foreign intervention in Haiti – independent since enslaved people revolted in 1804 – means most Haitians foresee less help than hindrance in the request.

Here’s a brief on the complexities of international responsibility in the face of Haiti’s crisis.

Does Haiti need intervention?

“I can’t say that the government controls the situation in the country right now,” admits a Haitian government appointee who asked not to be named. As a result, lives are at stake after gangs closed access to one of the country’s main fuel terminals, forcing gas stations to shutter and hindering essential services like banks and hospitals.

Though the official – like many Haitians – holds antipathy for any international involvement in the nation’s affairs, they concede that Haiti obviously needs short-term help to secure rule of law.

“If we have some kind of foreign intervention, maybe we can have some change quickly,” says the official.

But, in the long run, they and other Haitian observers note, the country will still be left with the problems it has always had.

What has gone wrong and what has gone right with interventions?

While interventions have brought temporary stability, it’s rarely lasting – and new problems often ensue, says Frantz Voltaire, a Haitian author, professor, and filmmaker living in Montreal.

The impulse to intervene in Haiti, overtly with troops and humanitarian aid, or opaquely through diplomacy and carrot and stick economics, depended on the crisis at hand. And it has always carried with it the whiff of what one Haiti watcher calls “neocolonial trappings.”

Poverty and violence in Haiti can have political repercussions when waves of migrants land on the shores of other Caribbean nations and the United States. So tinkering behind the scenes to prop up a government or spirit away a besieged president, or outright help to restore rule of law, might help those foreign governments more than the Haitian government. Humanitarian crises like hurricanes and the catastrophic 2010 earthquake can be cause for compassion and huge outlays of aid that solve momentary problems but not necessarily long-term structural ones.

Haitian suspicions are stoked by the long history of outside intervention starting with 17th-century French colonization and slavery and the huge debt of reparation imposed by France after Haiti won independence. The U.S. occupation in the early 20th century set the stage for the Duvalier family dictatorship from 1957 to 1986. And there have been several military and peacekeeping missions in the past 35 years.

The legacy of this history is seen in Haiti’s dysfunction: Since the fall of the Duvaliers in 1986, there have been 15 presidencies – only one of them widely hailed as democratically elected. Most recently, after they were brought in to help after the catastrophic 2010 earthquake, U.N. peacekeepers were believed to have introduced cholera to the water supply and were involved in a sexual abuse scandal.

It doesn’t help that Haitian institutions are depleted and disorganized, says Mr. Voltaire. At the moment, for example, the National Assembly has so many unfilled seats that a quorum can’t be reached. And Prime Minister Henry is seen by many as illegitimate because he was never confirmed by the Assembly.

On the other hand, says Robert Maguire, a Haiti expert and retired professor at George Washington University, a share of that disarray is a product of the global powers that meddled in Haitian politics and unfit leaders.

Is there an international responsibility to intervene?

Intervention of any sort is always vulnerable to accusations of interference – even when invited in a dire situation like Haiti faces today.

But global powers should feel a certain responsibility to Haiti, says Robin Derby, a scholar of Caribbean affairs at the University of California, Los Angeles and an opponent of military intervention.

“We need to begin discussions with groups outside of government for a way forward,” she says. While the U.S. government, for example, doesn’t typically deal with nongovernmental bodies, there are strong grassroots organizations in civil society in Haiti. One such group of civic, religious, and political groups – after Mr. Moïse’s assassination last year – developed the Montana Accord as a path forward, starting with a provisional government to take over from Mr. Henry and hold elections.

Dr. Maguire suggests that as a starting point, the U.S. needs to enforce its own laws, particularly when it comes to international weapons trafficking and money laundering by Haitians and Haitian Americans in the U.S. who are instrumental in funding the violence in Haiti.

Planting trees – and hope – in a flood-prone Nigerian town

Developing nations are bearing the brunt of extreme weather caused by the climate emergency. In Nigeria, some communities are creating their own solutions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ahmad Adedimeji Amobi Contributor

Twenty-five years ago, a storm ripped the roof off Soladoye Gbenjo’s house and dumped his belongings in the surrounding flooded fields of Igbajo, a district of windswept hills in southwestern Nigeria.

After replacing his roof, Mr. Gbenjo, an agriculturist, wanted to make his home safer. So he planted dozens of trees around it.

That decision inspired locals to begin a huge tree planting project that is now bearing fruit.

One of the highest levels of deforestation in the world means Africa’s most populous nation has lost all but 4% of its primary forest. Trees can help mitigate damage in storm- and flood-prone areas. Leaf canopies reduce erosion, while branches and roots act as a drag for wind and floodwater.

In recent weeks, more than 1.5 million Nigerians have been affected by flooding in 29 of the country’s 36 states. Igbajo has been largely spared, in part because of residents’ proactive measures.

Almost every compound today has seedlings sprouting around houses: teak, gmelina, afara, and maple. Locals also pooled their money to donate about 40 hectares of land to turn into a juvenile forest. This year, volunteers are on track to plant 20,000 saplings.

Watching recent floods unleashed across the country prompted resident Funke Abu to volunteer her time during a planting expedition. “It took me two days to pick 1,000 gmelina seedlings,” she says proudly.

Planting trees – and hope – in a flood-prone Nigerian town

A quarter of a century after the event, Soladoye Gbenjo still remembers the storm that changed everything. For months during the rainy season, battering rains tore through Igbajo, his rural community in the southwestern Nigerian state of Osun. Then came a wind that tore off the roof of his house, and dumped most of his belongings in the surrounding flooded fields.

Mr. Gbenjo, an agriculturist, realized something: His house, like most in the district of steep, windswept hills, was too open to the elements.

After replacing his roof, Mr. Gbenjo did the only other thing he could think of to make his home safer – he planted dozens of trees around it.

Mr. Gbenjo did not know it then, but that decision was a seed that would come to fruition more than two decades later, as the community found itself grappling with the increasing ravages of climate change.

“I developed an interest in tree planting from what happened to me,” says Mr. Gbenjo, now an octogenarian, pointing with a trembling hand at the dozens of trees he has planted around his house over the decades.

Trees can help mitigate damage in storm- and flood-prone areas. Leaf canopies reduce erosion caused by falling rain and provide a surface area for water to evaporate; and tree branches and roots also act as a drag on wind and floodwater, reducing the speed of both.

Nigerians need all the help they can get tackling floods, which are predicted by scientists to rise as the climate emergency gathers pace. Already the country has one of the highest levels of deforestation in the world. As the oil-producing nation grapples with a rapidly growing population, trees are being lost to urbanization, wood burning, and environmental disasters such as oil spills. An annual deforestation rate of about 3.5% translated to the loss of around 14,587 hectares in 2020. Today, Africa’s most populous nation has lost all but 4% of its primary forest.

In recent weeks, much of Nigeria has been hit by devastating floods that have affected 29 of the country’s 36 states.

Caught off guard by extreme weather events, Nigeria’s government has struggled to contain the catastrophic fallout. Widespread deluges caused by extreme rainfall and the release of excess water from a dam in neighboring Cameroon has displaced 1.4 million citizens and killed 500 in the past month alone, according to government officials.

But in Igbajo, residents have long since banded together to try to plug the gaps left by government inaction. As is common in Nigeria, the community of around 25,000 residents has an informal association tasked with resolving local disputes and issues that rarely reach state – or even local – government offices. As floods ravage large parts of the country, residents in Igbajo have been largely spared in part thanks to that association.

When Mr. Gbenjo began planting his trees 25 years ago, the chairman of the Igbajo Development Association immediately saw the advantages it would bring. And so, in a series of spontaneous gatherings, Shola Fanowopo asked the well-respected Mr. Gbenjo to talk to other community members about the benefits of planting trees.

So convinced were locals by the plan, that they pooled money to buy about 40 hectares of land to turn into a juvenile forest. That forest, in turn, would serve as a reservoir for eventually repopulating the entire district’s depleted trees, they hoped.

But first, they needed the actual trees.

Olalere Ajayi, a local farmer, was one of dozens who was convinced to sign up after seeing a neighbor’s roof torn off during a violent storm.

That made him realize the “need to protect my house,” Mr. Ajayi says, while walking through rows of young saplings on the edge of the community.

Within a year, almost every compound had rows of seedlings sprouting around houses. Residents planted gmelina, afara, and maple saplings common to the area, hardy and fast-growing trees.

Out in the surrounding fields, farmers also planted teak trees – whose firm grain makes it particularly useful for weather control – alongside their cash crops of cocoa, cassava, and yams.

In the first year, about 2,000 trees were planted, Mr. Fanowopo says. This year, volunteers are on track to plant a whopping 20,000 saplings, making a total of 50,000 trees planted since the project launched.

Like about 40 other residents who regularly volunteer, Mr Ajayi can often be found pitching in, either planting seedlings into small nylon bags; spraying growing saplings to keep insects and disease at bay; or digging older saplings to transplant them to where they’re needed.

Not all of those trees make it. Some seedlings don’t germinate, while others die after being uprooted to be transferred.

“The weather,” Mr. Gbenjo notes dryly, often doesn’t help.

Then there’s a lack of funding to maintain and fuel the trucks used to transport the trees across different locations – now even more difficult amid rocketing costs of diesel. And with inflation hitting a 17-year high, residents of the rural community are having to tighten belts, meaning the project is being put on the back burner.

Nigeria has announced several strategies to tackle deforestation, such as REDD+ – a United Nations-backed project launched at the COP26 climate summit last year, which aimed to limit the number of trees being cut down. But local residents and researchers say such plans rarely translated into results on the ground, with most state governments lacking the financing and data needed to make significant progress.

Agriculturists say initiatives like the one in Igbajo could be successfully transplanted to other communities, though that would require more input from government agencies.

“Hopefully the government will wake up and take action,” says Ugwu Shedrach, a young agriculturist and soil scientist in Nigeria’s central Nasarawa State.

In Igbajo, residents say they are determined to press ahead regardless. Watching recent floods unleashed across the country prompted Funke Abu to volunteer her time toward a planting expedition. “It took me two days to pick 1,000 gmelina seedlings,” she says, weary but satisfied.

Points of Progress

From beach to desert, efforts that add up

When leadership sets a positive tone for a community’s conduct, the results can be transformative. In our progress roundup, a Western U.S. program in prisons is nurturing nature. And on Australian coasts, towns and their volunteers have significantly reduced the trash on beaches.

From beach to desert, efforts that add up

1. United States

Incarcerated individuals are helping to save a keystone plant. Sagebrush ecosystems have shrunk by half in recent decades, due in part to forest fires that have swept across the western United States.

Since 2014, people imprisoned at 18 facilities across eight states from California to Montana have tended over 500,000 plants, feeding, watering, and weeding them and monitoring their health. The seedlings’ success rates when replanted are three times that of simply planting seeds in the affected areas, according to program coordinator Holly Hovis.

Participants in the program learn horticulture and team-building skills that can contribute to their employability once they are released, although they are not paid for their work. “It’s all completely voluntary by the inmates, and there’s usually a waitlist for people to join,” said Ms. Hovis. “They get so much peace of mind, stress relief, and the chance to work with, not against, their peers.” Recidivism research has shown positive rehabilitative effects from garden and environmental programming.

Sources: Reasons To Be Cheerful, Insight Garden Program

2. Senegal

Senegal broke a West African record with women occupying 44% of its new government’s seats. In 2010, the country became the second nation in the continent, after Rwanda, to require gender parity in government. Senegal mandates that women make up half of the candidates in each political party’s slate.

While achieving parity in local elections is still a challenge, the country ranks fourth in Africa for gender parity in parliament, according to the Geneva-based Inter-Parliamentary Union, and 18th in the world. “In the past, women were involved in political campaigns – but we were seen as performers, wearing beautiful clothing and singing,” said Mariama Cissé Mbacké, a participant in a leadership workshop given by the Women’s Association of Senegalese Jurists. “We brought our communities together, and paved the way for men to be elected. ... But we are no longer followers. We’re claiming our spot.”

Sources: Agence France-Presse, American Jewish World Service

3. Spain

The largest solar plant in Europe is now operating in Spain. The facility in the western region of Extremadura uses 1.5 million solar panels and will produce enough energy to power over 334,000 homes. In addition to helping reduce dependence on volatile energy markets, the plant contributes to the country’s goal of generating three-quarters of its electricity from renewables by 2030.

In recent years, solar power capacity has surged in Spain, one of the sunniest countries in Europe. Rooftop solar capacity on residential and business properties grew by 102% between 2020 and 2021, and solar energy cooperatives have made headway.

Sources: Bloomberg

4. India

India’s digital revolution has connected millions of people to the internet. The government launched “Digital India” in 2015 to bring more of the population online. At the time, only 19% of India’s population accessed the internet; today, almost 60% of the country has access, supported by falling prices for mobile data. Rural India saw a 13% growth rate to 299 million internet users over the past year, or 31% of India’s rural population.

Critics point out that the government has imposed more internet lockdowns than any other democratic country. But many users have experienced a transformation in their daily lives. “We had never imagined that we would get electricity or roads,” said Jay Shriram Sharma, a resident of the village of Kanda in the Himalayas who now uses video calls from his home to speak to his grandson, a doctor in Delhi. In some of the most remote villages where digital infrastructure is the most difficult, residents can access “common service centers” to pay bills or access documents.

Sources: BBC, The Economic Times

5. Australia

Plastic pollution along the Australian coast decreased by an average of 29% in just six years. From improved household waste collection to local beach cleanups, municipalities have made a concerted effort to reduce coastal litter. Scientists surveyed 183 shore sites in 2018 and 2019, comparing the data with surveys from 2012-13, and found that litter – which is almost three-quarters plastic – fell by as much as 73%.

While the amount of waste varies significantly among regions, depending on geographic conditions or the proximity of cities, the study offers evidence that raising public awareness and investing in concrete programs can lead to positive results. “It’s an amazing testimony of how much can change and how quickly you can see that change in the environment,” said Denise Hardesty, a co-author of the study by the government’s research agency. “Almost 30% in six years is really heartening and can help people understand the impacts of our behaviours.”

Sources: The Guardian, One Earth

Books

Humans use tech to connect. A novelist explores whether it’s working.

How much does technology alter human behavior? It’s a question that invites a deeper debate on the nature of connection and communication.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

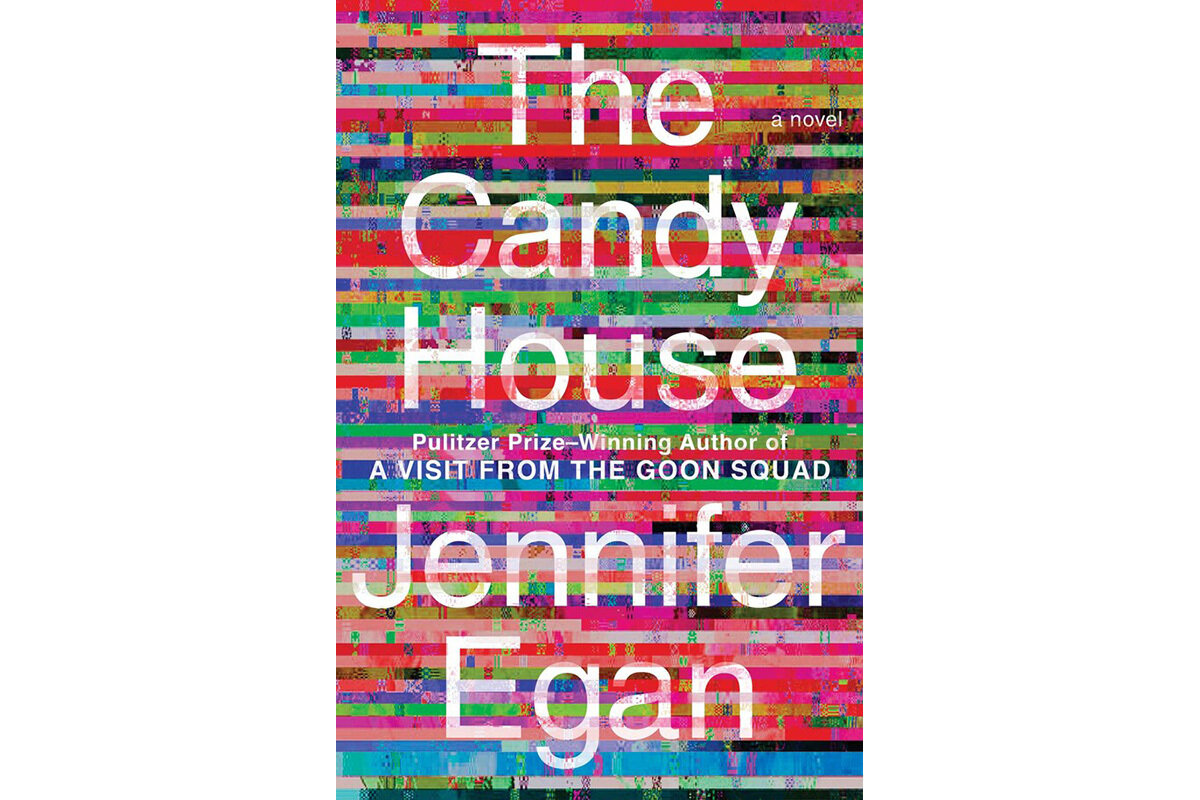

American writer Jennifer Egan’s fascination with human reactions to technology sits at the heart of her novel “The Candy House.”

Told in a dizzying array of narratives and styles, “The Candy House” is an exploration of our interconnectedness, but also our desire for real connection.

The book delves into the dangers of mass surveillance, the performative pressures of social media, and the consequences for “eluders” – those who go to great lengths to reject this brave new world.

But lest you think “The Candy House” is in the same dystopian realm as Aldous Huxley’s 1932 classic, Ms. Egan is here to set you straight. This is not a dystopian novel and was never intended to be.

“Dystopia is kind of uninteresting to me,” she says in an interview. “I feel weary of a post-apocalyptic landscape in which everything has gone wrong… [This book] is such an environment of humor and even hilarity and absurdity, and one in which it’s pretty optimistic.”

But that’s not to say she isn’t perplexed by our current relationship with tech. In fact, it was a driving force when she wrote this book. “I ask the question again and again whether we are being changed internally by technology,” she says.

Humans use tech to connect. A novelist explores whether it’s working.

I first met author Jennifer Egan in late September at the Festival America, a Paris book fair celebrating some 70 North American authors. Hundreds of literary fans milled around the mazelike configuration of tables, stacked books, and writers at the salon du livre, in hopes of making a brief but meaningful connection with their favorite authors.

Ms. Egan was seated calmly amid the flurry, a lighthouse in the storm, and asked if we could speak later, over Zoom, so that she could “stay present” for the people who had shown up to see her.

It was apropos, given that her latest book, “The Candy House,” delves into our deep need for connection, but also, authenticity, as we are increasingly overwhelmed by technology’s slow but steady takeover.

It is also fitting, then, that the first thing that happens when she and I speak again is that my Wi-Fi cuts out. As I sit devising the few choice phrases I’d like to say to my internet company, Ms. Egan doesn’t mince words about our relationship to tech: “We can’t go back.”

In “The Candy House” – a sibling novel to her 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “A Visit from the Goon Squad” – the reader follows some 14 characters’ twists and turns as they navigate a world dominated by Own Your Unconscious, a technology created by Bix Bouton – a demigod à la Mark Zuckerberg – that uploads users' memories onto a cube, so they are then available to others.

Told in a dizzying array of narratives and styles – from first person plural to epistolary to an instruction manual for spies – each chapter of “The Candy House” is an exploration of our interconnectedness, but also our desire for real connection.

The book delves into the dangers of mass surveillance, the performative pressures of social media, and the consequences for “eluders” – those who go to great lengths to reject this brave new world.

But lest you think “The Candy House” is in the same dystopian realm as Aldous Huxley’s 1932 classic, Ms. Egan is here to set you straight. This is not a dystopian novel and was never intended to be.

“Dystopia is kind of uninteresting to me,” she says. “I feel weary of a post-apocalyptic landscape in which everything has gone wrong. ... [This book] is such an environment of humor and even hilarity and absurdity, and one in which it’s pretty optimistic.”

But that’s not to say she isn’t perplexed by our current relationship with tech. In fact, it was a driving force when she wrote this book. “I ask the question again and again whether we are being changed internally by technology,” she says.

If “The Candy House” is any indication, the people developing the internet, cell phones, and social media are probably not part of a master plan to destroy us. Thanks to technology, she writes: “tens of thousands of crimes solved; child pornography all but eradicated; Alzheimer’s and dementia sharply reduced by reinfusions of saved healthy consciousness; dying languages preserved and revived; a legion of missing persons found; and a global rise in empathy that accompanied a sharp decline in purist orthodoxies – which, people now knew, having roamed the odd twisting corridors of one another’s minds, had always been hypocritical.”

Ms. Egan’s own relationship with technology would appear to be love-hate. Despite her fascination with our interactions with it, she says she regularly stashes her cell phone in another part of the house and is not tempted in the slightest by social media. As for misadventures down the internet rabbit hole, she does it like everyone else, but, she says, “I rarely feel good about a lot of time spent noodling around online, and I don’t know many people who do feel good about it.”

She cites “The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America,” the 1962 work by Daniel Boorstin, as eerily prescient about the performative, curated nature of social media today. Mr. Boorstin essentially coined the term “famous for being famous” (a celebrity is “a person who is known for his well-knownness”) and claimed that press conferences and presidential debates were manufactured events, with the singular goal of gaining press coverage.

Today, according to Ms. Egan, “a lot of what we see on social media is people trying to know each other’s interiors and trying to share the content of one’s own interior because that’s such a human wish and a human need.”

Cue society’s almost painful desire to be “seen” on a mass scale and social media’s ability to deliver – from the “humble brag” of the friend on Facebook who simply can’t figure out where he should donate his economic stimulus check, to the exhausted mother who posts a wholly unflattering Instagram selfie showing her futile attempts to put the kids to bed.

“I’m fascinated by the desire for authenticity ... [but] I literally never say to myself, ‘How can I live an authentic life?’” she says. “The minute you’re trying to do something authentic, it’s a sign that you’re in territory that is preventing you from doing that.”

The desire to cut the act is so strong that it pushes some characters in “The Candy House” to the extremes, most spectacularly Alfred, whose “intolerance of fakery” has led him to releasing a primal scream in public places, in search of genuine human reactions and authenticity.

But perhaps resistance to technology’s pull is futile. As the character Chris Salazar – the head of an entertainment startup fighting to preserve people’s privacy – says about externalizing one’s consciousness, “The collective is like gravity: Almost no one can withstand it. In the end, they give it everything.”

Ms. Egan’s own advice on how to exit the “paradox of authenticity” is an obvious one: Get off the screen.

And so it is that as I am saying goodbye to her, I find myself trapped in a brilliantly ironic moment of life imitating art. There’s me, shamelessly seeking connection by relaying an anecdote that would link Ms. Egan and me through one of my closest friends, and my Wi-Fi once again going on the fritz.

“I’m losing you again,” she says, as the line cuts in and out. “I think it’s a sign that we have to end.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

California’s wrinkled brow at sports gambling

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In two different ballot measures next month, voters in California have an opportunity to approve legal sports betting in America’s most-populated state. Yet polls indicate the two measures, known as Propositions 26 and 27, will not pass. Why the public’s hesitation?

For one, the state is saturated with betting places, from 66 tribal casinos to 23,000 stores selling lottery tickets. Two, California doesn’t even know how many people struggle with gambling addiction.

Yet another reason may lie in concerns about “how Americans think about wealth, luck, and success,” as historian Jonathan Cohen puts it in a new book, “For a Dollar and Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America.”

While the modern state lottery has been around for decades, its impact is very mixed and could be influencing public debates on legal sports betting, which Mr. Cohen calls “the new frontier of American gambling.”

California’s wrinkled brow at sports gambling

In two different ballot measures next month, voters in California have an opportunity to approve legal sports betting in America’s most-populated state. Given the 40 million people who live there, the potential market for this fast-paced type of gambling could be the second largest in the world, behind that in Britain.

In promoting the measures, special interest groups have broken state spending records. On the table are billions of dollars in yearly revenue from legal sports betting.

The referendum vote is being closely watched in other states. Since a Supreme Court ruling four years ago opened the floodgates to sports gambling, more than 30 states have lifted their bans. The rest have been reluctant to follow. Yet they could shift if California joins the rush to tap the money in sports betting.

Despite so much at stake, polls now indicate the two measures, known as Propositions 26 and 27, will not pass. Why the public’s hesitation?

For one, the state is saturated with betting places, from 66 tribal casinos to 23,000 stores selling lottery tickets. “The last thing California needs is more gambling,” states an editorial by the Bay Area News Group.

Two, California doesn’t even know how many people struggle with gambling addiction, according to a new state audit. The social costs in dealing with this public health issue could skyrocket with legal sports betting. The San Diego Union-Tribune cites “legitimate apprehensions over the risk to society when the barriers to legally betting on sports are lowered.”

Yet another reason may lie in concerns about “how Americans think about wealth, luck, and success,” as historian Jonathan Cohen puts it in a new book, “For a Dollar and a Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America.”

While the modern state lottery has been around for decades, its impact is very mixed and could be influencing public debates on legal sports betting, which Mr. Cohen calls “the new frontier of American gambling.”

One big problem with lotteries, he says, is that state agencies running them appear to run counter to the purpose of all other branches of state government: “to promote the greater good, not to sell a product to the public.”

As new types of gaming continue to grow, he says, government guidance on gambling remains “lacking and unsuited,” especially as it is well known that state lotteries hit hardest on “a population that is disproportionately poorer, less educated, and nonwhite.”

Lessons from state lotteries could be giving pause to many Californians about sports betting. Americans, Mr. Cohen advises, need to think critically about the “economic forces” that limit social mobility and financial security, driving many people to gamble.

California may be due for a discussion on whether a belief in luck – or “hitting the jackpot” – has anything to do with wealth and success.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Capable? Yes!

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

If we’re feeling in over our head with a task we’ve been called upon to do, there’s strength and inspiration to be found in considering our God-reflected nature and abilities.

Capable? Yes!

Sometimes we may have doubts about our abilities. At times they may seem so heavy that we feel as though we’re impostors, having no business attempting the jobs we’re expected to do.

When I’ve felt that way, inspiration from the Bible has helped me. For instance, Christ Jesus said, referring to himself, “The Son can do nothing of himself” (John 5:19). Yet virtually everywhere Jesus went, wonderful regeneration, victories, and healing works took place.

Was this false modesty? No. He explained that God was behind everything that he did: “The Father that dwelleth in me, he doeth the works” (John 14:10).

There’s good news for you and me: While we, of course, are not Jesus, we too express the same heavenly Father. We are the self-expression of the Divine. So qualities that stem from God – such as intelligence and wisdom – are always at full strength and present in each of us as God’s spiritual offspring.

When we’re presented with a difficult or overwhelming job or task, we don’t need to ruminate on whether we as mortals have what it takes. Instead we can draw on what we know of our true, spiritual nature as reflecting the rich goodness, intelligence, insight, and strength of God.

“Man is God’s image and likeness; whatever is possible to God, is possible to man as God’s reflection,” writes the Monitor’s founder, Mary Baker Eddy, in her “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896” (p. 183). Just as the moon never originates its own light, but reflects only the sun’s light, we don’t originate ability; we reflect God’s infinite abilities.

As we come to realize and accept this, fears and doubts begin to evaporate and we feel a calm strength and hope.

Once, I took on a new job in a field I’d never worked in before and, additionally, suddenly had several dozen people reporting to me and looking for leadership. I felt out of my element, to say the least.

So I decided that each day, I would treasure that idea that we are all reflections of God’s nature, rather than mortals attempting to accomplish things through personal force of will.

It took a little discipline, as sometimes self-absorption and rumination would make me oblivious to the inspiration that our Father is always imparting. However, each time I released a sense of self-importance – even a slight one – I found myself more receptive to God’s gifts of reflected intelligence and inspiration.

Through prayer, my awareness of God solidly working within me – and all my colleagues, too – expanded. I was able to successfully fulfill my job duties, which soon expanded even more.

“Through God we shall do valiantly,” says the Bible (Psalms 60:12). Yes, through God we do valiantly – and capably. Praying from that basis helps us connect with our genuine selves – capable and productive – and overcome feelings of impostor syndrome. As Mrs. Eddy explains in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” the textbook of Christian Science, “Man’s genuine selfhood is recognizable only in what is good and true” (p. 294).

For God’s glory and splendor alone, we shine brilliantly by reflected light.

A message of love

A three-day harvest

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow, when our Scott Peterson examines how Ukrainians are preparing for winter, especially as Russian airstrikes target energy infrastructure.