- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Split-ticket voters were declared extinct. They may decide the Senate.

- Military veterans as election workers: Can they rebuild trust in vote?

- High aims, high hurdles: Building fairness into political reporting

- Imran Khan is stable after march shooting. Is Pakistan?

- Connecting through language

- How a documentary captures the human-robot bond

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Trump and a third run: Why he might announce early

Many signs are now pointing to a third presidential run by Donald Trump. At a Monitor Breakfast yesterday, former senior Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway told us she expected him to announce “soon” after Tuesday’s midterm elections. Other outlets echoed that news today, with one saying the former president’s “inner circle” is looking at Nov. 14, and another saying he could announce “possibly as soon as” that date.

Former President Trump has long been hinting at a 2024 run, and he did so again yesterday at a rally in Sioux City, Iowa. “I will very, very, very probably do it again,” he said.

Declaring this soon would be extraordinarily early; candidates typically announce in the year preceding the election. But Mr. Trump could have several reasons for moving quickly. He reportedly believes that being a declared candidate could insulate him from various criminal investigations, including ongoing probes of efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s victory in 2020.

And announcing his candidacy could help shore up his base of support, as polls show many Republican voters – including some Trump supporters – increasingly say they’d like someone else as their 2024 nominee.

Mr. Trump’s entrance would have immediate ripple effects. There are at least a dozen other credible GOP candidates, many a generation younger than Mr. Trump, who would feel pressure either to jump in or bow out.

It would also likely supercharge the Democratic side – in ways that could actually help President Biden. He has long made clear that he ran in 2020 to counter Mr. Trump, whom he and much of the Democratic base view as a threat to democracy.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that Mr. Trump is just toying with the media – something he’s done in the past – and he isn’t actually planning an announcement at this time. Still, the political world has to take the hints seriously.

At our breakfast, Ms. Conway discussed why Mr. Trump might want another term. “He's got a great post-presidency life,” she said. But he’s had only one term and “was just getting started. He loves this stuff and wants to continue.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Split-ticket voters were declared extinct. They may decide the Senate.

In recent election cycles, party loyalty – and deep suspicion of “the other side” – has meant fewer voters willing to split their vote. But this time around, they could decide control of the Senate.

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Clad in a gray hoodie, khakis, and sneakers, Ed LeCates sat this week on a bench next to the courthouse in downtown York County in Pennsylvania. Mr. LeCates is a proud Republican. He used to sit on the state committee. But he finds himself contemplating something different this election: voting for a Democrat for governor.

His loyalties are being challenged by gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano, a Republican who was present at the Jan. 6 insurrection, though he didn’t enter the Capitol and has been charged with no crime. Mr. Mastriano lags 10% behind Democrat Josh Shapiro.

“What happened on Jan. 6 was sickening, sad, atrocious,” says Mr. LeCates.

Some political analysts wrote obituaries for the split-ticket voter after the 2016 election. But this year, voters in at least nine statewide elections could pick governors from a different party than their U.S. senator.

Reasons include candidate quality, the power of incumbency, and shifting questions that can be summed up with “What have you done for me lately?” But some say the mutineering goes a little deeper – a pushback against identity politics in favor of personal agency and individual expression in a country where coloring outside the lines has long been considered de rigueur.

Voting is “the only power we have left,” as Irvin Bryant, a Black Atlanta voter, puts it.

Split-ticket voters were declared extinct. They may decide the Senate.

While parties and pundits may cast America as neatly lined up into tribal camps, competing in a zero-sum contest for the future of the republic, allow Richard Bink to break the mold.

The Savannah, Georgia, veterinarian voted early at Islands Library here on Georgia’s Whitemarsh Island as ibises veered through an ultramarine sky. He usually votes Republican, but has turned to the center lately, letting his party membership lapse.

On Wednesday, Mr. Bink pulled the lever for his Republican incumbent governor, Brian Kemp, and also for his sitting Democratic senator, Raphael Warnock.

His bifurcation is in large part a rejection. He says he cannot stomach Herschel Walker, the controversial Republican candidate and former football star endorsed by former President Donald Trump.

“Quality candidate, and all that,” says Mr. Bink, who also talks about wanting to protect democracy as a reason for his support for a Democratic senator.

Mr. Bink’s vote – and the votes of others like him – could be key. After all, Mr. Walker and Senator Warnock are locked in a dead heat.

Situated just east of Savannah, suburbs like this one are where political scientists say most of America’s political independents can be found: middle class, fairly racially diverse, center-right leaning, and, like Mr. Bink, possessing a keen sense of civic pride.

Many political analysts wrote obituaries for the split-ticket voter after the 2016 election, when every state that elected a Republican senator also voted for Mr. Trump, while every state that picked a Democratic senator voted for Hillary Clinton. But this year, polling suggests that voters in at least nine states – including Georgia and Pennsylvania – could wind up picking governors from a different party than their U.S. senator.

Reasons include candidate quality, the power of incumbency, and uneven fundraising. But for some voters, the mutineering may even go a little deeper – a pushback against today’s rigid partisanship in favor of personal agency and individual expression. Voting is “the only power we have left,” as Irvin Bryant, a Black voter from Atlanta, puts it.

“Voters who split their tickets tend to not follow politics as closely as the people who are strongly partisan, so I’m not sure we have a complete understanding of how they make up their mind,” says David Kimball, a University of Missouri political scientist who, as co-author, tried to answer that question in the book “Why Americans Split Their Tickets.” “In a way, ticket splitters represent some – I don’t know if ‘rationality’ is the right word. We want elections to respond to shifts in voter opinion, and split ticket voters, for better or worse, are [examples of] that.”

Consider Ed LeCates. Clad in a gray hoodie, khakis, and sneakers, Mr. LeCates sat this week on a bench next to the courthouse in downtown York County in Pennsylvania. Open in front of him was a book on algebra. A police officer stood near a ballot drop box by the courthouse.

Mr. LeCates is a proud Republican. He used to sit on the state committee. But he finds himself contemplating something different this election: Voting for a Democrat for governor.

Specifically, he’s not sure he can bring himself to vote for gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano, a Republican who was present at the Jan. 6 insurrection, though he didn’t enter the Capitol and has been charged with no crime. “What happened on Jan. 6 was sickening, sad, atrocious,” says Mr. LeCates.

Conversely, he believes Attorney General Josh Shapiro, the Democratic candidate, projects competence. “I could live with Shapiro because at least he would be honest,” says Mr. LeCates. Mr. Shapiro is the only Democrat Mr. LeCates is contemplating voting for.

Polls show that many Pennsylvanians are mulling a similar choice: Mr. Mastriano lags 10% behind Mr. Shapiro, while the Senate race is neck and neck. Spoiler alert: Mr. LeCates has yet to finalize his decision.

In the 1980s, as many as 1 out of every 3 voters split their ballots. As parties grew more ideologically homogenous and politics became increasingly cloaked in identity, that declined to just over 1 out of 10 in 2016. And though Republicans gained seats in the House even though Mr. Trump lost in 2020, only Maine deviated from party uniformity on presidential and senate votes. Thirty-five House districts in 2016 saw “cross-over” results. By 2020, that number had dropped to 16, according to analysis by the University of Chicago.

“People vote out of habit, and it really does get to be like sports: You root for the laundry rather than the person wearing it,” says Andrew Smith, a political scientist at the University of New Hampshire in Durham.

Split-ticket dynamics are different from state to state, but Pennsylvania and Georgia could be seen as bookends.

As Rust Belt cities like Pittsburgh continue to shrink, parts of Pennsylvania have been drawn into a politics of scarcity. They vote differently than Philadelphia and its booming suburbs. Meanwhile, parts of fast-growing Georgia ponder the politics of prosperity, says political scientist Lara Brown.

Those dynamics are “changing the way politics are happening in those states,” says Ms. Brown, author of “Amateur Hour,” about presidential character and leadership. “Politics is really about who gets what, when, and how, so when you are growing ... then it is a politics of, how do we divide the pie? But when it’s shrinking, it becomes a zero-sum game.”

Pennsylvania – the nation’s center of political gravity and perhaps its ultimate battleground on Nov. 8 – has been ahead of the ticket-splitting trend.

In 2019, Pennsylvania removed the option to automatically vote straight ticket – or “all of the above” – joining 15 others that have done the same since 1994.

The state in some ways kicked off the split-ticket era in 1956 when Republican Dwight Eisenhower carried the Keystone State while a sliver of voters – about 6 percentage points – crossed over to vote for U.S. Senate candidate Joseph Clark, a Democrat.

Pennsylvania has its share of solid-red and solid-blue areas. Its ticket splitters are bunched in large part into the Lehigh Valley. Northampton County, the Allentown suburbs, voted for Joe Biden for president and Mr. Shapiro for attorney general in 2020, but elected Republicans for treasurer and auditor, seats that have only been Republican once in the past 60 years.

Those districts are not a huge chunk of Pennsylvania’s total electorate, says Republican strategist Sam Chen, in Allentown, “but it’s enough that those areas are what make up the final determination of how the state is going to go.”

Mr. Chen, also a political scientist at Northampton Community College, has a keen personal sense of the crossover tensions. He is voting for Mr. Shapiro for governor and Mehmet Oz, a Republican, for Senate. His main reason is aversion to their opponents: Mr. Mastriano, the Republican, for governor and John Fetterman, a Democrat, for senator.

“I don’t think people have migrated. I think party apparatuses have,” says Mr. Chen. “Candidates always matter.”

In a phone interview, Chad Robson, a Pennsylvania human resources consultant, largely agrees. Candidates who vote the party line are a turnoff for him, he says.

“Traditionally, I’ve been more on the conservative side of social issues, but those are becoming less important to me, especially as we’ve seen the economy tank lately,” he says. “So the economy is probably my top issue currently.”

Tara Deihm, a registered Republican, has lived in Pennsylvania her whole life. Wearing a cardigan and slacks, she’s taking a break from her job at a community development financial institution in Lancaster.

Though she has voted Republican across the board for years – except in 2016, when she didn’t vote for president, and 2020, when she voted for Mr. Biden – her concerns about abortion rights and middle-class economic opportunity are spurring her to vote Democratic for both governor and senator. But she still plans to vote for Republican candidates down-ballot.

“I pay a lot of attention to the candidates and what they stand for,” says Ms. Deihm. “I also base [my decision] on the past and what they show themselves to be.”

Nearly 700 miles to the South, Baoky Vu has traveled a difficult road away from being a GOP voter right down the ticket.

Mr. Vu, a former Dekalb County election official in Georgia, was censured in 2021 by the local GOP for pushing back against claims of massive voter fraud in 2020. It wasn’t his first tussle with his party. A Vietnamese immigrant, Mr. Vu also resigned as a presidential elector in 2016, saying he couldn’t cast a ballot for Mr. Trump.

This year, Mr. Vu will cast his vote for Mr. Kemp as governor and Senator Warnock to retain his Capitol seat. He sees it as too risky for American democracy to cast his ballot for Mr. Walker, who has faced allegations of spousal abuse and, more recently, claims from two women that they had affairs with Mr. Walker and the anti-abortion candidate paid for their abortions. Mr. Walker has also said he had been diagnosed with dissociative personality disorder, though he says he has overcome it.

In the days before the election, polls show Governor Kemp has a commanding lead in his race, while Mr. Walker is neck and neck with Senator Warnock, despite being dramatically outspent.

For most Republican voters, what Mr. Walker says or does seems to matter less than what he represents: a reliable vote for conservative policies they see as America’s salvation. But even a small number of defections could make the difference in a tight race.

“The election is a story of a small sliver of moderate, mostly white, lean-Republican voters who have shown they are willing to vote for a Democrat,” says Bernard Fraga, a voter preference expert at Emory University in Atlanta.

But some Black voters, too, may be splitting their tickets on Tuesday.

Clarence McCloud, a Black voter from Savannah, may help offset some of Mr. Walker’s difficulties among white suburbanites by splitting his ticket the other way. He is voting for Stacey Abrams, a Democrat, for governor and Mr. Walker for Senator. “Walker is just my kind of guy,” explains Mr. McCloud.

Even as Black voting power has increased in Georgia faster than in any other state, voting patters are becoming less monolithic. A mid-October poll by Data for Progress found that 15% of Black voters planned to vote for Mr. Kemp, up from 13% in 2018.

Still, some Black independents say they would have been more open to voting Republican had the party nominated someone other than Mr. Walker.

“I look at fiscal and economical issues, which is why I’ve voted for Republicans in the past,” says Pashuen Thompson, an African-American psychiatrist in Atlanta. “But if you put someone unqualified up it comes off as a cynical ploy, and it insults a lot of voters like me.”

Back on Whitemarsh Island, Mr. Bink, knows that his choices may be critical to the outcome in an evenly divided state and country.

But he admits to having a deeper concern. He is well aware of Georgia’s central role in the 2020 election and an ongoing investigation in Fulton County into whether former President Trump illegally interfered in the administration of the election.

Voting, to him, isn’t just about participation in democracy, but protecting it.

“That’s why we’re here, right?” says Mr. Bink, nodding toward the long line forming outside Islands Library.

Staff writer Christa Case Bryant contributed to this report.

Military veterans as election workers: Can they rebuild trust in vote?

Amid an estimated shortfall of 100,000 election workers, U.S. military veterans are increasingly stepping up to help. Some see benefits flowing both ways – to the individuals as well as to society.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Retired Marine Corps Lt. Col. Joe Plenzler recalls the day when he and his wife, also a retired Marine Corps officer, got to vote in person after years of absentee ballots due to their career assignments. “It was so cool,” Mr. Plenzler recalls, “watching the rights you swore your life to defend being exercised by the people.”

Now they are part of Vet the Vote, an effort among veterans groups to get former troops to the polls not just to vote but to help, at a time of election staffing shortages and distrust in the system.

Veterans acknowledge that the presence of veterans among those storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 last year may call into question whether their presence at the polls should inspire confidence – or whether it may be seen by some as a veiled threat.

Still, overall public trust in the military remains high. And since the recruiting effort began earlier this year, veterans organizations have signed up some 65,000 from their ranks.

Vet the Vote co-founder Ellen Gustafson says that many Americans, “despite information to the contrary, ... truly believe that elections have been compromised.” She says the group wants to help restore a sense of “Wow, we do this” to democracy.

Military veterans as election workers: Can they rebuild trust in vote?

As a U.S. military family, Ellen Gustafson and her husband have lived and served with plenty of people who “really aren’t similar to you.”

And, she says, she likes that. Lately, she’s particularly appreciated not being stuck in an echo chamber – her social media feeds are filled with “a lot of different political opinions. I’ve always found it an incredible benefit.”

Yet a midterm election season liberally populated with candidates who have signaled that they may refuse to accept the outcome – unless they win – backed by a number of voters who appear to support such sentiments, got her thinking.

“Despite information to the contrary, people truly believe that elections have been compromised,” she says. “That norm, that bedrock that we’ve all agreed on – somebody wins, somebody loses, and we move on – that is shaky.”

She helped form an organization called Vet the Vote to encourage former troops to volunteer as poll workers, and teamed up with other veterans groups across the country to do the same.

It’s an effort to do in America what service members frequently have been called upon to do abroad: shore up the promise of fairness previously presumed to be inherent in electoral systems.

“It’s a great group of people who know how to get their jobs done for the greater mission – in this case, democracy,” says Ms. Gustafson, a Navy spouse. Though they don’t advertise their military background at the polls, vets bring skills from their service, supporters point out: They are schooled in small-group leadership, tend to take rules and regulations seriously, and have solid training in defusing situations in which people get hot under the collar.

In an election season in which a number of swing states have warned of poll worker shortages – some 60% are over the age of 60, an age group particularly affected by pandemic health concerns – it’s a particularly vital endeavor, analysts add.

Americans’ trust in the military shaken by Jan. 6

Yet veterans acknowledge, too, that in the wake of former troops being involved in the storming of the U.S. Capitol last year, their presence – which once may have inspired confidence in the electoral process – may now be seen by some as a veiled threat at the polls.

“I think the view of veterans in America took a bit of a hit after Jan. 6,” says Jeremy Butler, chief executive officer of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

The challenge is to make the process about civics rather than about politics, he adds. Jan. 6 “was not a good example of who we are.”

Since the recruiting effort began earlier this year, veterans organizations have signed up some 65,000 of their ranks, putting a considerable dent in a national shortfall currently estimated at roughly 100,000.

Volunteering at the polls is a chance not only to show up for a country in need, Mr. Butler says, but also to demonstrate that “we want to continue to serve honorably, and that we can have differences politically but come together to support our political process – the absolute antithesis of what happened at the Capitol that day.”

“The most significant thing I’ve done as a citizen”

Retired Marine Corps Lt. Col. Joe Plenzler recalls that when he and his wife, also a retired Marine Corps officer, came home from their local polling station, they were deeply moved.

After years of mailing in absentee ballots because of various assignments and deployments, they had voted in person. “It was so cool,” Mr. Plenzler recalls, “watching the rights you swore your life to defend being exercised by the people.”

His wife later volunteered to work at the polls. “She said, ‘I’ve got to tell you, that was the most significant thing I’ve done as a citizen in my life,’” Mr. Plenzler recalls. “I said, ‘That’s a big statement – I want to be part of that.’”

The training and work on voting day were “rigorous,” he says. “I’m reading off numbers, someone else is recording numbers, there’s a tamper-proof case, there’s a paper copy of every vote. I’m like, ‘Is this ‘The Hunt for Red October?’”

Getting more vets out to volunteer, it occurred to Mr. Plenzler, could be a way to convince skeptics of the integrity of the process. While he wasn’t inclined to such skepticism himself, it nonetheless “left me super-confident in how elections are run,” he says. “You can’t walk away from that training and not be.”

It’s an open question whether voters will have similar confidence in the former service members who raise their hands to help out on Election Day.

Trust in the military has slipped in recent years: 56% of Americans said they had “a great deal of trust and confidence” in the armed services in 2021, down from 70% in 2018, according to the Ronald Reagan Institute.

Still, that figure was far higher than for other public institutions, including Congress at 10%, for example.

Countering extremism, bridging divides

It is in part the esteem in which veterans are generally held that made their participation in the Jan. 6 attacks more shocking, says Katherine Kuzminski, director of the Military, Veterans, and Society program at the Center for a New American Security.

Those figures were relatively “small numbers, but they had a large impact,” she adds. Getting vets to volunteer at the polls is a “way to demonstrate that the majority are good members of the community, invested in the health of democracy.”

Civic engagement could also help counter extremism in the ranks among vets who find themselves looking for a sense of belonging after they leave the service. The search to fill that void can make them easy marks for extremist organizations anxious to take advantage of their credibility and affinity for camaraderie, analysts add.

“The post-9/11 community is always looking for more ways to serve,” Mr. Butler says. “It’s a real opportunity to give back to the country and our fellow citizens.”

It also helps to bridge a civil-military divide that troubles many veterans, adds Mr. Plenzler, who serves on the board of We the Veterans Society for American Democracy. “You take a step towards your community, and they’ll take a step towards you.”

Leaving uniforms and personal politics behind

Efforts to recruit nonpartisan poll workers are particularly important, analysts note, given that those who continue to deny the outcome of the 2020 presidential election are also calling on supporters to sign up to serve within America’s local democratic infrastructure.

Former Trump adviser Steve Bannon is a prominent supporter of this so-called precinct strategy, which has also been endorsed by Donald Trump as a way to “take back our great country from the ground up.”

The Vet the Vote movement anticipated that it would be associated with partisan attacks on democracy, “from ‘They’re militarizing the polls’ on the left to ‘This is a bunch of lefty vets’ on the right,” Mr. Plenzler says.

For this reason, the group has been deliberate in its nonpartisan choices, down to the color of its online swag. Everything from the water bottles to the tote bags is purple (a combination of blue and red), and there are no camouflage prints in sight. The idea, it says, is to distance the organization, and the vets who take part, from any militaristic overtones.

Roman soldiers left their red capes and armor in camps outside the city when they returned from war, notes Mr. Plenzler. “It’s symbolic of our return from military duty to rejoin with our fellow citizens.”

“We’re not naive or Pollyannaish, pretending there aren’t challenges,” Ms. Gustafson says. “But we want to reconnect to this election, not by ‘I’m red’ or ‘I’m blue’ and ‘Let’s fight it out’ but by ‘Wow, we do this. Elections are what we do in America – and we’re the best at this.’”

Listen

High aims, high hurdles: Building fairness into political reporting

How does the Monitor approach political reporting with consistent fairness? In an era when politics-as-usual can sometimes mean devaluing facts, our politics editor says it’s a challenge.

What does it take to maintain fairness in political reporting at a divisive time, one in which “controlling the narrative” and “rousing the base” can mean pushing facts aside?

“One of the expressions that you hear at the Monitor a lot is ‘light, not heat,’” says the Monitor’s politics editor, Liz Marlantes. “And I think that can be a particularly beneficial approach in the realm of politics.”

Practically speaking, she tells the Monitor’s Samantha Laine Perfas, that means “trying to bring an objective and helpful perspective to various themes and issues and races in a way that will be a service to readers.”

That doesn’t mean presenting “both sides” in a way that creates false equivalencies when one side or the other strays from reality. It means acknowledging that there’s tremendous complexity around most issues, and calmly showing as many of those as possible so readers can form their own conclusions – and learn to push back on misinformation. It also calls for active listening, and not just to politicians. Reader feedback is always welcome.

“Sometimes we learn something new that we didn’t know about,” says Liz, “and at other times it’s just a chance to have a dialogue.” – Samantha Laine Perfas, multimedia reporter

This is an audio interview. Prefer to read it? You can find a transcript here.

Keeping It Fair

Imran Khan is stable after march shooting. Is Pakistan?

Behind the drama of mass marches and assassination attempts, Pakistani politics is mired in broad popular mistrust of the nation’s leaders and their ties to the military.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan had planned to be marching into Islamabad next week at the head of hundreds of thousands of supporters, demanding early elections. Instead, he was the target of an apparent assassination attempt on Thursday that he later blamed on the government and intelligence services.

But behind the drama reigns a widespread atmosphere of distrust and discord among Pakistani voters, say ordinary citizens and political analysts, after decades of opaque dealings between the country’s political leaders and the military.

“Why should we have any faith in politics when our leaders have consistently demonstrated that they are only interested in power?” says Asif Ghani, who works at a toy store.

“The mess we are in today is largely due to the fact that political leaders are not united on key issues concerning the country’s political system,” says veteran political analyst Raza Rumi, who teaches at Ithaca College in New York.

“They all think that making bids and deals with the army will give them power, so when they are in opposition they look for a deal, and when they are in government they defend the armed forces,” Mr. Rumi adds. This has just eroded trust in the political system even further.

Imran Khan is stable after march shooting. Is Pakistan?

Seven months after he was ousted by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan had planned to march triumphantly into the capital, Islamabad, next week at the head of hundreds of thousands of his supporters and compel the government to call early elections.

Instead, he was rushed to the hospital on Thursday after a man opened fire on his convoy, injuring Mr. Khan in the foot. By Friday evening he had recovered sufficiently to hold a press conference, blaming the apparent assassination attempt on Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and a top general in Pakistan’s premier intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence.

But behind the drama reigns a widespread atmosphere of distrust and discord among Pakistani voters, say ordinary citizens and political analysts, after decades of opaque dealings between the country’s political leaders and the military.

“Why should we have any faith in politics when our leaders have consistently demonstrated that they are only interested in power?” says Asif Ghani, who works at a toy store in Rawalpindi, a city adjacent to the capital.

“When the current government was in opposition, they were demanding free and fair elections and Imran was saying that the parliament would complete its term,” Mr. Ghani recalls. “Now Imran is saying he wants free and fair elections, and the government is saying it intends to complete its term. What is the ordinary person supposed to conclude from all this?”

For local political commentator Murtaza Solangi, Mr. Khan’s crusade against graft and nepotism, branding all his political opponents as “a band of crooks,” has polarized Pakistani society.

Yesterday’s apparent assassination attempt on Mr. Khan, he argues, is just the latest symptom of a country rent by discord. “The seeds of bigotry and intolerance sown by our deep state and nourished by many politicians, including Imran Khan himself, are now bearing fruit,” he says.

Deep distrust

In the months since his ouster as prime minister, Mr. Khan has launched a three-pronged attack against the Pakistani army, Washington, and the coalition government led by Mr. Sharif, all of which he blames for his downfall.

His campaign has propelled his party to a string of by-election victories, but has been less successful in mobilizing support for his planned siege on the capital. Mr. Khan had expected a tsunami of demonstrators to follow him from Lahore to Islamabad and overthrow the government; in fact, until yesterday’s attack, the “Freedom March” had struggled to gather momentum.

That, says Ahtasham Mangool, a manager in a medical company in Rawalpindi, is because people do not trust politicians to work for the public good. “Imran Khan says he will bring accountability into the system but look at the people he has around him,” he says. “These are the same people who have never let anyone prosper in their constituencies. How can we believe that they will ever let anyone succeed except for themselves?”

With annual inflation running at around 26% in October, there is widespread dissatisfaction with the government, but not much enthusiasm for Mr. Khan as an alternate. Though his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, won the most recent parliamentary by-election last month, only 35% of voters bothered to cast a ballot.

Such is the mistrust in the political system that some even question whether the attempt on Mr. Khan’s life was genuine. “I think Imran Khan did it himself because his march was failing and he wanted to get a boost from the public,” says Saleem, a daily wage laborer who asked to be identified only by his given name. “Everyone knows that the army runs the country and Imran Khan made a big mistake by crossing them. The generals will never let anyone else take control.”

The ever-present army

Civil-military discord has troubled Pakistan throughout its 75-year history, and the country has oscillated between overt and covert military rule.

Mr. Khan’s critics contend that his victory in the 2018 elections would not have been possible without the army’s interference, and they chided him when he was serving as prime minister for having been “selected,” rather than elected. But as soon as rifts developed between Mr. Khan and his military backers, the same opposition exploited this breakdown to return to power.

“The mess we are in today is largely due to the fact that political leaders are not united on key issues concerning the country’s political system,” says veteran political analyst Raza Ahmad Rumi, who teaches at Ithaca College in New York.

“They all think that making bids and deals with the army will give them power, so when they are in opposition they look for a deal, and when they are in government they defend the armed forces,” Mr. Rumi adds. This has further eroded trust in the political system.

“Imran Khan used to say that the military establishment was on his side. Now he blames them for removing him from power,” points out toy salesman Mr. Ghani.

Mr. Khan differs from his predecessors, argues Mr. Rumi, in that he doesn’t pretend to stand for constitutional supremacy. “His public posturing does not demand that the military should go back to the barracks,” Mr. Rumi says. “In fact, what he says is that the military should act on his behalf and install him because he is cleaner and more honest than his political opponents.”

How the apparent attempt on his life will impact Mr. Khan politically is still unclear. But “as a shrewd politician who uses every crisis as an opportunity,” says Mr. Solangi, “Imran will use this as a pressure valve to make maximum gains.”

Commentary

Connecting through language

Better communication between Arab and Jewish Israelis would increase neighborliness, this Heart of a Nation Teen Essay Competition winner says. And she sees a way to help that happen. To read other winning entries, visit Teens Share Solutions to Global Issues.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Noga Novis Deutsch Contributor

Arab Israelis make up over 20% of Israel’s population. However, less than 10% of Jewish Israelis speak Arabic. None of my Jewish friends speak Arabic. The adults in my life only know a few phrases, but from their army service. “Jib el awiah” (Pass me your ID) and “Wakf walla batuchak” (Stop or I shoot) do not make for civil conversation. Jewish Israelis expect Arabs to be fluent in Hebrew, but don’t hold ourselves to the same standards.

I propose that Jewish students start learning Arabic in kindergarten and focus on expanding their vocabulary. Classes should also be taught in experiential and innovative ways that will provide positive experiences for the students. For example, movies, podcasts, and other media have proven to be effective in teaching and immersing learners in new languages. Students can put on plays in Arabic, create pop-up museums using Arabic, and engage in other activities that prompt the creative use of the Arab language.

Arab and Jewish schools should also interact more so that students can experience live conversation with their peers.

In order for us to work on our society’s big issues, we first need to break down the barriers we’ve erected between us.

Connecting through language

This is one of three winning entries in a teen essay contest for Americans, Israelis, and Palestinians that was sponsored by Heart of a Nation. The essay prompt was “What do you most want to improve about your own society and how?” Winners were chosen by the organization; the Monitor supported this cross-cultural program by agreeing to publish the winners’ essays. Views are those of the writer, who lives in Kibbutz Hannaton, Israel.

Earlier this year, I was waiting at the train station when I heard a little boy crying. I walked over to see if I could help, but when I asked him what was wrong, he responded in Arabic. I couldn’t understand him; although I assumed that he was lost, I felt helpless. Eventually, his mother found us and thanked me in Hebrew. We were able to communicate because she knew my language.

Arab Israelis make up over 20% of Israel’s population. However, less than 10% of Jewish Israelis speak Arabic. None of my Jewish friends speak Arabic. The adults in my life only know a few phrases, but from their army service. “Jib el awiah” (Pass me your ID) and “Wakf walla batuchak” (Stop or I shoot) do not make for civil conversation. This language barrier is significant. It bars us from being able to communicate with our neighbors and fellow citizens in their native language. Jewish Israelis expect Arabs to be fluent in Hebrew, but don’t hold ourselves to the same standards. We strive for peace in Israel and intend to see each other as equals – but most of our population can’t even hold a simple conversation in Arabic.

I believe that there’s a simple solution: We need to start teaching Arabic again! Arabic used to be a compulsory course, but even the schools that still teach it now only offer it to older students, which is more ineffective. It isn’t a high-priority class and is mostly taught as a literary subject. This prevents the students from having a large vocabulary, because it prioritizes learning the different letters rather than the relevant words for day-to-day life.

I propose that students start learning Arabic in kindergarten and focus on expanding their vocabulary. The lessons should be prioritized, especially in the younger grades. Classes should also be taught in experiential and innovative ways that will provide positive experiences for the students. For example, movies, podcasts, and other media have proven to be effective in teaching and immersing learners in new languages. Students can put on plays in Arabic, create pop-up museums using Arabic, and engage in other activities that prompt the creative use of the Arab language.

Arab and Jewish schools should also interact more. We can pair schools, and once a month the schools would meet and engage in communication so that they can experience live conversation with their peers.

In order for us to work on our society’s big issues, we first need to break down the barriers we’ve erected between us.

Noga is a high school senior who lives on a kibbutz in Israel with her family and cat. She has been training as an aerial acrobat for nine years and has been a counselor in the youth movement Noam for three years.

To read other Heart of a Nation Teen Essay Competition winners, visit Teens Share Solutions to Global Issues.

Film

How a documentary captures the human-robot bond

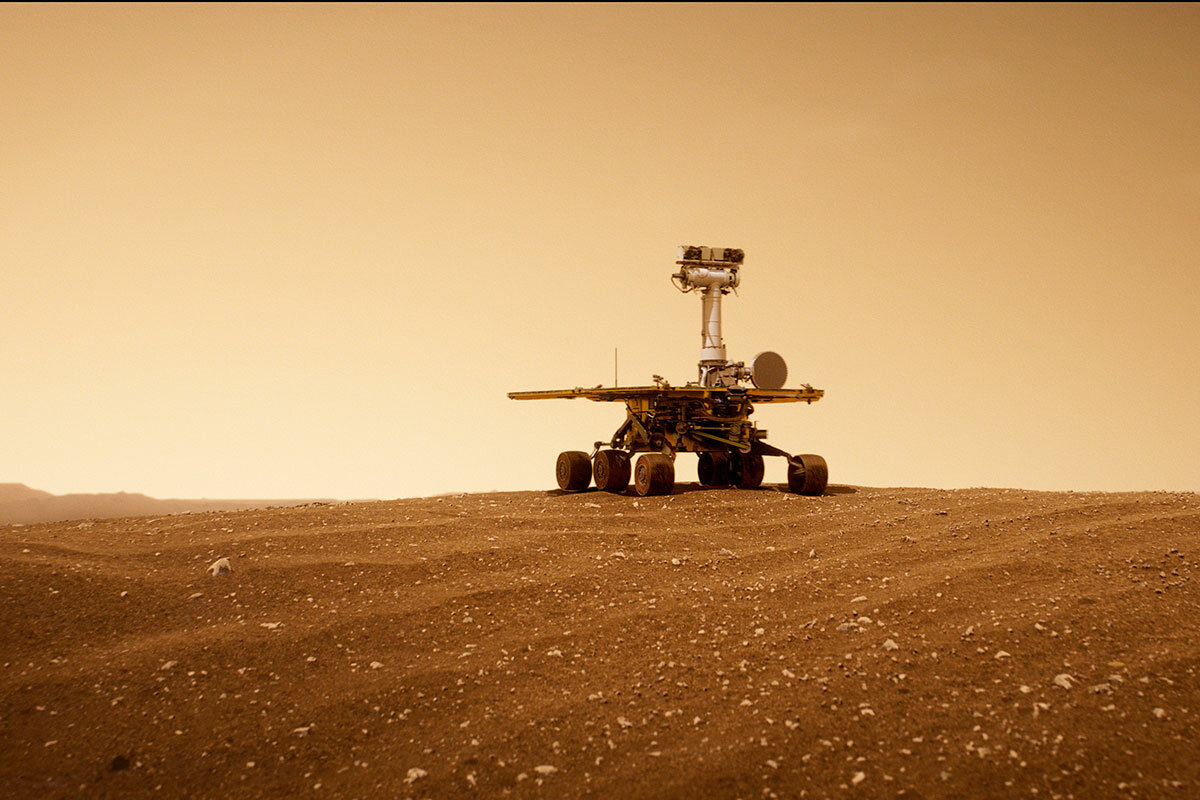

When director Ryan White talks about his documentary “Good Night Oppy,” featuring Mars space rovers and their human handlers, he describes the bonds and emotions of family – and the teamwork it took to exceed expectations.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Mars rovers Opportunity and Spirit departed Earth in 2003. Upon successfully touching down on the red planet, they were only expected to last about 90 days. The scientists and engineers at NASA were flabbergasted that the pair survived for many years.

In his latest documentary, “Good Night Oppy,” director Ryan White examines the doting relationship between the control room crew members – people from across the globe – and their robotic progeny. It’s a story of gumption: When a machine gets mired in quicksand 140 million miles away, how do you rescue it?

The connection between humans and nonhumans interested the director. As did ideas like discovery and exploration, especially as they relate to childlike awe and imagination.

“Why can’t we as adults have that feeling anymore?” he asks in a recent Zoom interview, adding, “This group of humans did. They were going to a place that had literally never been seen before by mankind. And they were doing it by this avatar of theirs that they had created by their own design. And so I wanted the audience of the film to feel that sense of wonder.”

How a documentary captures the human-robot bond

It takes a village to raise a robot. A new documentary, “Good Night Oppy,” chronicles the familial bond between a pair of Mars rovers and their human “parents” at NASA. Opportunity and Spirit departed Earth in 2003. Upon successfully touching down on the red planet, the duo were only expected to last about 90 days. The scientists and engineers were flabbergasted that the pair survived for many years. In his latest film, director Ryan White (“Good Ol’ Freda,” “The Case Against 8”) examines the doting relationship between the control room crew and their robotic progeny. It’s a story of gumption. When a robot gets mired in quicksand 140 million miles away, how do you rescue it? “Good Night Oppy” is a testament to egoless team effort. The film ends its multidecade story with the launch of a new rover named Perseverance. Mr. White spoke recently with the Monitor via Zoom. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What were the key themes you wanted to explore in the movie?

First of all, the connection between human and nonhuman was something I was very interested in. ... And then another big one is this idea of discovery and exploration, and especially with that sense of wonder and awe that we often have as children when we use our imaginations. ... Why can’t we as adults have that feeling anymore? And this group of humans did. They were going to a place that had literally never been seen before by mankind. And they were doing it by this avatar of theirs that they had created by their own design. And so I wanted the audience of the film to feel that sense of wonder.

What were your favorite backstories about what inspired these scientists and engineers to choose their careers?

I think it’s important to remind people that this isn’t just Americans working on these projects. So, Vandi Verma, she’s a rover driver. We have a little bit of her backstory in our film. She’s from India and she got a book on space exploration for her [seventh] birthday, and she knew that’s what she wanted to do. ... Almost everyone in our film was an outsider. ... We wanted to be very conscious of making sure people, kids, especially watching the film, would see themselves represented on the screen by a potential role model. Like [Ashitey Trebi-Ollennu] from Ghana, who grew up taking radios apart in his small town, is now one of the lead engineers.

What does this movie reveal about human ingenuity and leadership as tools to solve unforeseen obstacles?

Ingenuity is at the center of the film. And I would say even more so than leadership. For sure, leadership plays a massive role in that. But I would say [what] comes to mind even more than leadership are teamwork and collaboration.

Steve Squyres, who is the head leader of this mission ... is always very careful to stress, “I was the principal investigator. I have no idea how to do almost everything that made this mission successful. I knew how to do a very slim portion of this mission, and then the next person knows a very slim portion of this mission, and they have no idea how to do most of the other mission.” What’s integral to these types of missions – and it sounds cheesy, but it is inspirational – is this idea of [how] everybody has to come together and do their part to pull off something bigger than us.

I was struck when Steve Squyres said, “The whole project was bound together by that feeling of love. You’re loving the rover and you’re loving the people.”

It’s probably the last word you would expect a principal scientist to be using. ... But, yeah, I do believe it’s driven by love. And you can see it even when we’ve had screenings and you see [the team] get to see each other, because they move on very fast to other missions and they get split up.

Was there a moment when you, as the filmmaker, became similarly emotional?

I was allowed to go in July of 2020 – so it was the height of COVID – to Perseverance’s launch. ... My cameraman had a camera on [Moogega] “Moo” Cooper, who’s a young Black woman in my film, and she was one of the announcers for [the launch]. And so I could see on my cellphone him recording her reacting to the launch, because this is her baby. ... Seeing her emotion while I was feeling the earth rumble and watching the rocket launch from my camera ... I definitely teared up and probably stayed that way for 30 to 60 minutes.

“Good Night Oppy” is in theaters now and will be available to stream on Amazon Prime Video starting Nov. 23. It is rated PG for some mild language.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Alternate atmospherics at this year’s climate confab

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

More than 30,000 people are expected to gather in Egypt next week in the serious business of dealing with climate change. Frustration has been high ahead of this latest global conference on the issue. One reason is that weather disasters seem more frequent and intense while progress on carbon emission goals remains slow.

Feelings of anger and fear have come to dominate the annual confabs. Yet beyond the policy arena, a diversity of thinkers in science, philosophy, and religion is suggesting a recognition of different mental frameworks – ones that view a warming atmosphere less as a problem of moral action than as a call for a new mental atmosphere.

Much of that creativity involves efforts to reconcile science and religion. In Indonesia, a program has introduced a climate change curriculum at 50 Islamic boarding schools. Measures like these reflect an intent to draw on religious values to help cope with the effects of climate change. Yet they may be knocking on the door of something more profound – an approach that the late French thinker Bruno Latour described as the “new climate regime,” a challenge so profound to humans that it calls for new ways of thinking about material assumptions.

Alternate atmospherics at this year’s climate confab

More than 30,000 people are expected to arrive on the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt next week – government officials, industrialists, scientists, and activists – all gathering in the singular, serious business of dealing with climate change. Frustration has been high ahead of this latest global conference on the issue, the 27th convened by the United Nations since 1995. Greta Thunberg decided not to be there. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak wasn’t planning to attend until public pressure changed his plans.

One reason for the sour mood is that weather disasters seem more frequent and intense while progress on carbon emission goals remains slow. Wealthier countries are also not delivering on promises to pay poorer nations for the “loss and damage” caused by the climate effects of their earlier industrialization.

Feelings of anger and fear have come to dominate the annual climate confabs. These summits “have a culture which is zero-sum, hostage-taking, bargaining, negotiating games,” Alden Meyer, a policy analyst at E3G, a London-based climate change think tank, told The New York Times.

Yet beyond the contentious policy arena, a diversity of thinkers in science, philosophy, and religion is suggesting a recognition of different mental frameworks – ones that view a warming atmosphere less as a problem of moral action than as a call for a new mental atmosphere.

“Solving the problem of climate change will not be successful if we allow our fears to overcome us,” Tyler Giannini, co-director of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School, told The Harvard Gazette in April. “Solving the problem will require the strength, commitment, and creativity of our global community.”

Much of that creativity involves efforts, stirred by climate change, to reconcile science and religion. These discussions are emerging from diverse places, from Harvard’s Divinity School to The Nature Conservancy. In Indonesia, a program started earlier this year by the Center for Islamic Studies at the National University has introduced a climate change curriculum at 50 Islamic boarding schools. The curriculum is designed to instill in students an approach to environmental stewardship rooted in Islamic values.

Measures like these reflect an intent to draw on the diversity of religious values to help the world cope with the effects of climate change. Yet they may be knocking on the door of something more profound – an approach that the late French thinker Bruno Latour described as the “new climate regime,” a challenge so difficult that it calls for new ways of thinking about material assumptions.

That perspective will be at work on Nov. 13 during the two-week climate conference in Egypt. Representatives of the world’s major religions will gather at Mount Sinai, the site of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, to collectively affirm the utility of spiritual laws for the world’s response to climate change. Their gathering is not a passive petition for divine intervention. It is, as the various organizers put it, a “calling for reexamination of deep-seated attitudes and for identifying ways to transform these attitudes for the wellbeing of Earth.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Getting past who’s right and wrong

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Susan Booth Mack Snipes

When we’re open to the idea that everyone has a God-given ability to know and do what’s right, everybody benefits.

Getting past who’s right and wrong

In the flyleaf of my mother’s Bible is a sentence she’d written: “There’s no me to do right; there’s no me to do wrong; there’s just God and His faultless idea.”

That’s not to say that we don’t exist, or that what we do doesn’t matter. Rather, it means that there’s more to us than mortal personalities that are either good or bad. We’re God’s children, or ideas – spiritual and good – and therefore inherently capable of doing what’s right because God is the source of universal good. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, defined “Mind” in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” in part as “The only I, or Us” (p. 591).

These ideas helped me when my teenage daughter called in tears from camp. Her friends were doing something dangerous, and she asked them to stop. When they didn’t listen, she told her counselor, who brought the camp director to talk to the girls. This stopped the activity – but after that, the cabin mates wouldn’t speak to my daughter.

I assured her that she’d done the right thing, and said I would pray with her. But as I prayed, I struggled with how proud I was of my daughter for doing the right thing and with judging these other girls as not so good.

I thought about that sentence in my mom’s Bible and realized I had to be willing to give up the limiting notion of personal good and personal evil, and instead see that we are all God’s faultless ideas.

It took almost an hour to wrestle down the desire to hang on to personal good, but when I yielded to the truth, a beautiful peace came over me. Just then the phone rang, and my daughter’s cheerful voice said, “We’re all talking again!” And at a gratitude campfire later in the camp session, one of the girls said, without referring to this specific instance, “I’m grateful to be in a place where when you are doing something wrong, you are loved enough to be helped to stop doing it.”

God speaks to every one of us about our faultless being.

Adapted from the July 29, 2022, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

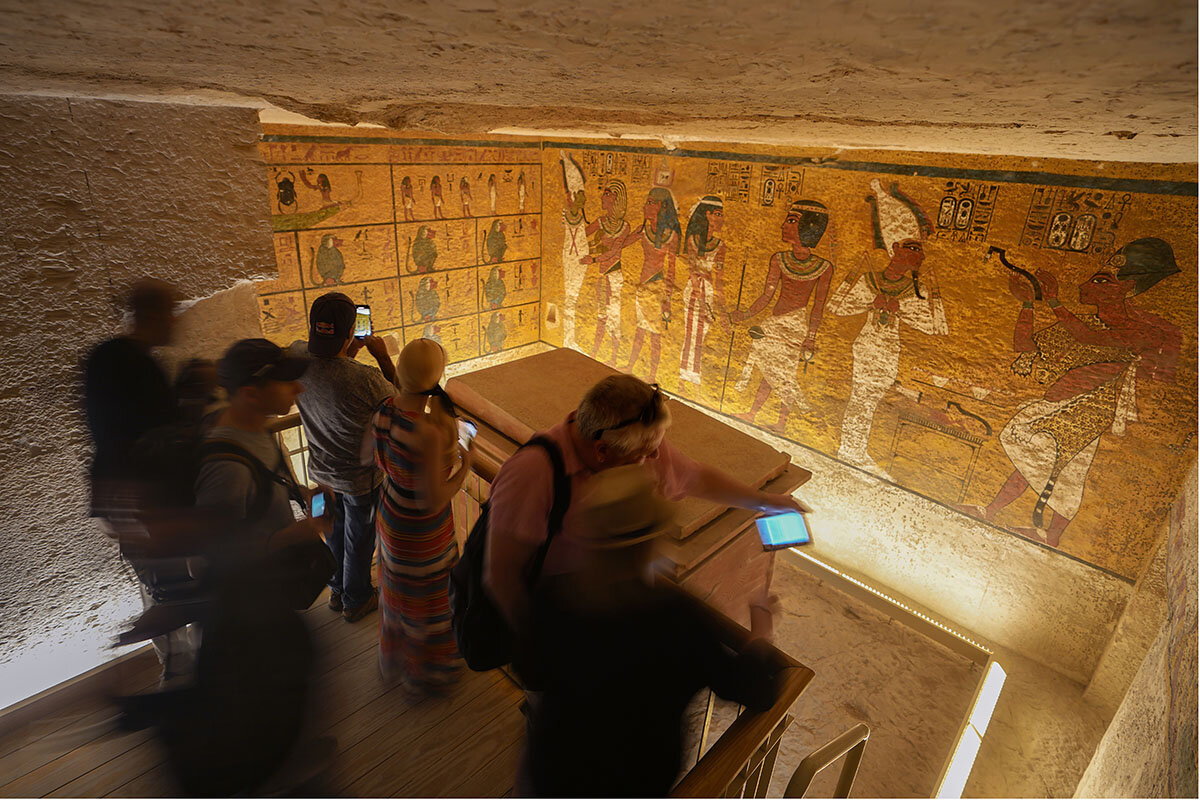

Inside Tut’s tomb

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come again Monday, when we look at the state of American democracy on the eve of crucial midterm elections.