- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘The heart of the human drama’ in an art museum

April Austin

April Austin

Art museums can feel like a world apart. Entering the marble halls and gleaming galleries often induces a state of curiosity and awe. The appeal of this kind of atmosphere led Patrick Bringley to leave his job at The New Yorker and work as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

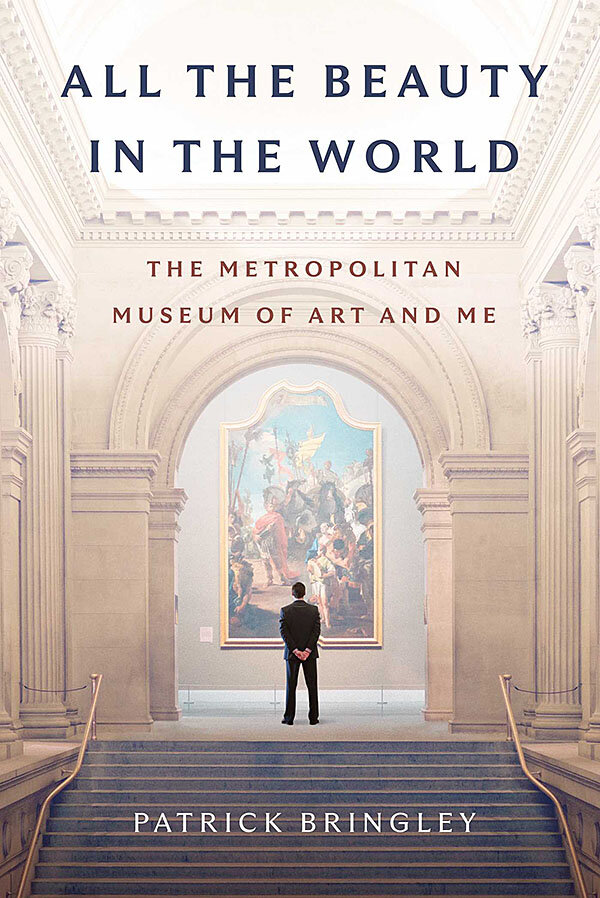

This week, Mr. Bringley’s memoir, “All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me,” arrives in bookstores to glowing reviews (ours is below).

His decadelong stint at the Met began in 2008, when he was in his early 20s and grieving the recent death of his brother. Spending his workday communing with art felt absolutely necessary.

“I relished the idea of spending quiet hours focused on things that seem fundamental, that have to do with the heart of the human drama,” he says in a video interview. “The museum as a whole feels like this sort of numinous place.”

While the book takes readers behind the scenes of one of the largest, most prestigious art institutions in the world, the most poignant passages deal with the author’s ability to be receptive to, and moved by, art.

“One thing that happens in an art museum is we make ourselves open,” Mr. Bringley says. “We turn on a part of our brain that allows us to feel the beauty and the wonder – of both big, cosmic things and also small, intimate things.”

Over time, the art he was guarding became a source of spiritual nourishment. Slowly, the grief receded, and he could take in the magnificent show – not only on the walls, but also in the galleries – of a parade of guards and visitors coming and going.

He says, “I was fortunate to have so much time to bring my defenses down and really let that whole story come in.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Taking on Trump: How 2024 might be different from 2016

A crowded GOP presidential field could help Donald Trump win the nomination again. But many factors are different – including Mr. Trump’s unique status as a “pseudo-incumbent.”

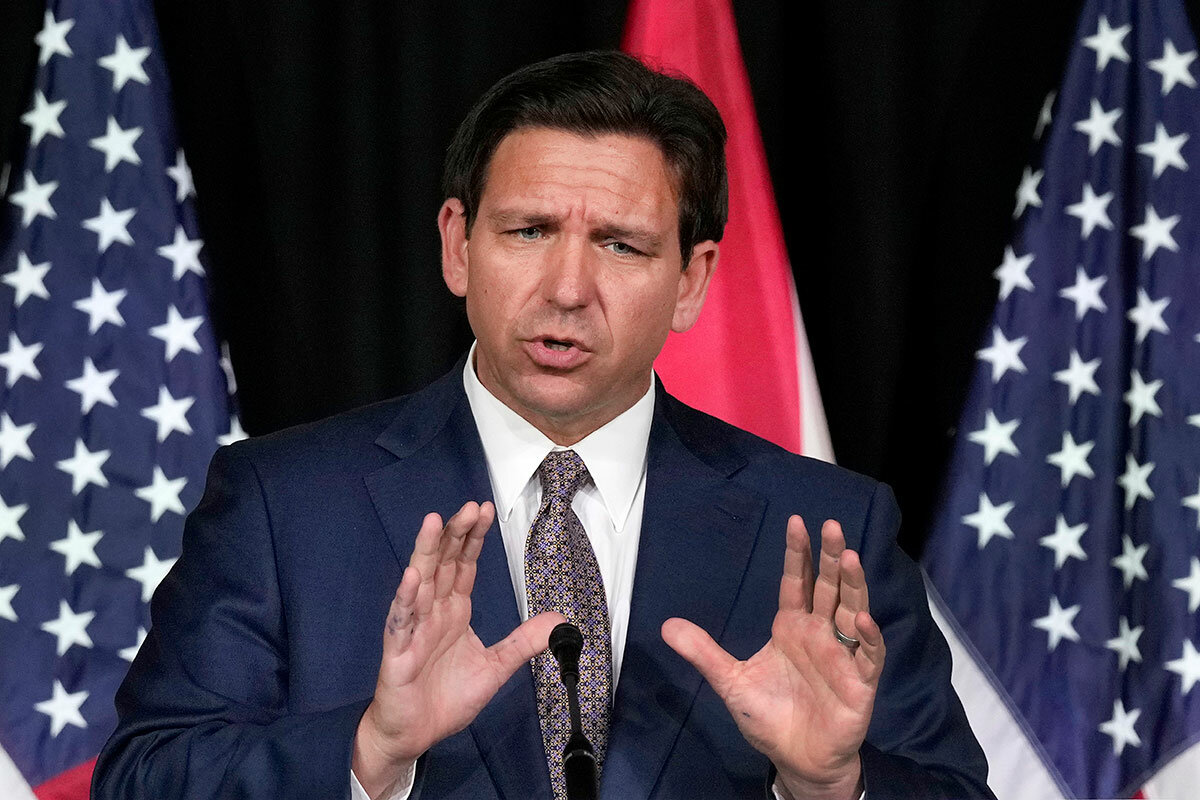

Nikki Haley, former governor of South Carolina, is now officially running for president – the first major Republican to take on former President Donald Trump, a declared candidate since November. Many other prominent Republicans are likely to follow, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, by far the strongest competitor against Mr. Trump in polls of GOP voters. Governor DeSantis is expected to announce in several months.

In a basic way, the math points to another 2016. A dozen or more prominent Republicans are expected to get in. President Joe Biden, an octogenarian struggling in the polls, presents a juicy target in his own anticipated run for reelection. And Mr. Trump commands a loyal following of GOP voters – not a majority, but enough to divide and conquer the rest of the field.

Still, political analysts say, the 2024 cycle is likely to be different in many ways. Mr. Trump is the first defeated one-term president to run for his old office in modern history – and as such, there’s no road map.

“They’re going to have this really crowded field, and tons of candidates that can’t really differentiate themselves from one another,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia.

Taking on Trump: How 2024 might be different from 2016

The battle has been joined.

Nikki Haley, former governor of South Carolina, is now officially running for president – the first major Republican to take on former President Donald Trump, a declared candidate since November.

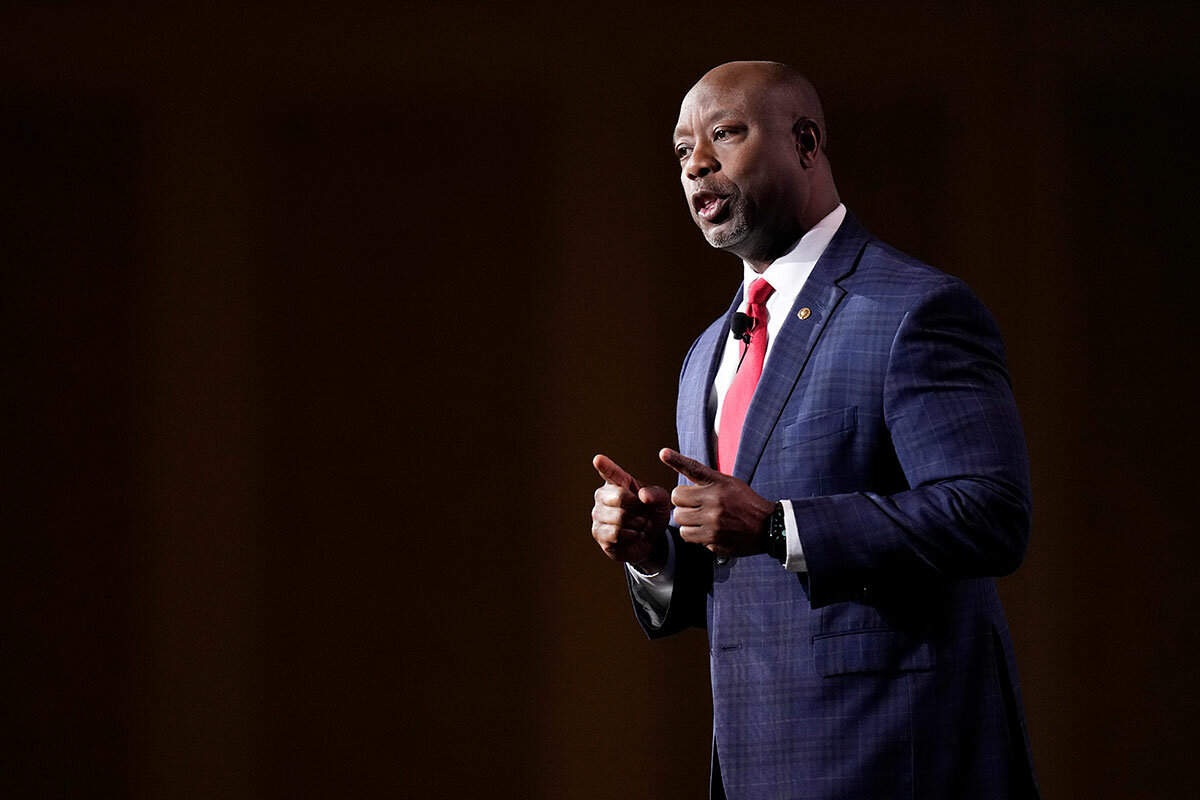

Tim Scott, a fellow South Carolinian and the only Black Republican in the U.S. Senate, launches a listening tour today for his own potential run. Mike Pence, the former vice president, is on a two-state swing ahead of his own possible campaign.

Many other prominent Republicans are likely to follow, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, by far the strongest competitor against Mr. Trump in polls of GOP voters. Governor DeSantis is expected to announce in several months.

All of which raises the billion-dollar question: Will the 2024 presidential cycle be a rerun of 2016, when Mr. Trump clawed his way to the Republican nomination by capturing pluralities of votes in winner-take-all primaries? Or will a new dynamic take hold?

In a basic way, the math points to another 2016: A dozen or more prominent Republicans are expected to get in. President Joe Biden, an octogenarian struggling in the polls, presents a juicy target in his own anticipated run for reelection. And Mr. Trump commands a loyal following of GOP voters – not a majority, but enough to divide and conquer the rest of the field.

“If not the presumptive nominee, he’s certainly the front-runner,” says Republican strategist Doug Heye. “Sure, his numbers have been dipping and we’ve seen instances where his message doesn’t resonate quite as much. But he’s still more than first among equals. He’s got a base; he gets more media coverage than anyone else; he has money in the bank.”

Still, political analysts say, the dynamic of the 2024 cycle is in many ways different from 2016. Back then, in the early going, Mr. Trump – a businessman and reality TV star – was a novelty act who shocked the GOP establishment, as when he called Mexicans rapists, criminals, and drug dealers in his announcement speech. Many Republicans didn’t take him seriously. Now, it’s clear anyone who discounts Mr. Trump does so at their peril.

And once again, Mr. Trump is playing a unique role. He’s the first defeated one-term president to run for his old office in modern history – and as such, there’s no road map. He is, in effect, a pseudo-incumbent, running to unseat an actual incumbent, each with a presidential record to run on.

Republican primary voters face a fateful decision. But it’s still early days. So far, Mr. Trump’s 2024 campaign has been remarkably low-key. Perhaps, some political observers suggest, his heart just isn’t in it; maybe he’ll change his mind about running.

Or, it may just be that he’s pacing himself. Some observers point to Mr. Trump’s influence in the 2022 midterms as a sign that he’s still very much in the game.

“They’re going to have this really crowded field, and tons of candidates that can’t really differentiate themselves from one another,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia. “They don’t know if they’re Trump; they don’t know if they’re not Trump. We’ve seen that dysfunction play out in Congress.”

The fact that so many prominent Republicans are running against Mr. Trump, or preparing to run, is evidence enough that he’s vulnerable.

In her campaign debut this week, Ms. Haley – who served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations under Mr. Trump – sought to thread the needle between distancing herself from her controversial former boss while also not attacking him. Her digs against Mr. Trump were indirect, as when she seemed to go after both him and the current president in her pitch for generational change.

“America is not past its prime. It’s just that our politicians are past theirs,” said Ms. Haley, who is in her early 50s. She also said she favored a “mandatory mental competency test for politicians over 75 years old.” Mr. Trump falls in that category, as does Mr. Biden.

She highlighted her parents’ background as immigrants from India, and her unique identity in GOP presidential politics as a woman of color. But Republicans, including Ms. Haley herself, are quick to say that their party doesn’t engage in “identity politics.”

“Republicans rebel against being told to vote for someone because of race, color, or religion,” says Chapin Fay, a GOP communications strategist in New York. Still, he adds, “Republicans want to expand the tent and live up to [former President Ronald] Reagan’s ideals.”

Indeed, the optimism that Ms. Haley sought to project in her campaign debut seemed to come right from the Reagan playbook. The “American era” hasn’t passed, she said. America is not a “racist country.”

But she also highlighted the culture war themes of race and education that have dominated the early going of the 2024 cycle – and have rocketed Mr. DeSantis to national prominence, and could also be Virginia GOP Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s calling card if he decides to run.

Ms. Haley, less widely known nationally than the Florida governor, may well have been smart to jump in first after Mr. Trump, earning several days of national media coverage. Her entrance drew relatively mild swipes from her former boss, whom she had once pledged not to oppose in a presidential race.

In an interview with Fox News Digital, Mr. Trump said he welcomed her to the race – even hinting at how the math works in his favor. “The more the merrier,” he said, adding, “I want her to follow her heart – even though she made a commitment that she would never run against who she called the greatest president of all time.”

The former president offered a sharper dig on Truth Social, calling her appointment to the U.N. ambassadorship in 2017 “a favor to the people I love in South Carolina” – i.e., getting her out of the governorship.

So far, Mr. Trump has not bestowed upon her a signature nickname. As more Republicans get in, however, he may feel duty-bound to deliver.

“Trump is in a kind of awkward situation,” says Dennis Goldford, a political scientist at Drake University in Iowa, which will hold the crucial first GOP nominating contest next year. “On the one hand, he takes it as personally offensive to him when people challenge him. But he also knows, the more the merrier.”

Some prominent Republicans note with disappointment that, in her announcement speech, Ms. Haley failed to mention the most courageous act of her governorship: removing the Confederate flag from the South Carolina State House grounds. The move, taken with bipartisan support, was a response to the 2015 massacre of Black parishioners by a white supremacist at a historically Black church in Charleston.

The issue of the Confederate flag remains fraught in the South, as some residents view it as a symbol of their heritage, not of racism.

Henry Barbour, longtime member of the Republican National Committee from Mississippi, says he became a Haley fan back in 2015 when the flag came down in Charleston.

“It was a powerful moment in South Carolina history,” Mr. Barbour says, noting that Mississippi removed the Confederate symbol from its own state flag in 2020. “It shows she’s willing to lead. ... She did the right thing. I’d encourage her to talk about that.”

Mr. Barbour is also a big proponent of highlighting diversity within the GOP, even while rejecting identity politics. The party is, in fact, diversifying, as seen in the slight uptick in the Black and Latino vote for Mr. Trump in 2020.

A message of inclusion will help the party win back some of the suburban voters it lost in 2016 and 2020, he says. “That’s where the aspirational message – addition versus division – helps us regain those lost voters.”

Why French protesters feel ignored on pensions

The French are taking to the streets to protest a planned increase in retirement age. While all agree reform is needed, many French are asking: Are we getting what we were promised?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Hundreds of thousands of French protesters have taken to the streets in recent weeks to demonstrate against the French government’s proposed reform to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64. Most say they're fighting to save a sacred – but broken – pension system.

But as the government’s retirement reform bill is debated at the National Assembly this month, there is an increasing disconnect between the public and the government about how best to do that.

The government has said that unless the French work longer, the numbers simply don’t add up: Without reform, the pension system will not be able to sustain itself for future generations. And though protesters say this is precisely their main concern, they don’t think working into old age is the right answer.

“In various studies, the French say that work is very important to them, not just the salary but what they get out of it personally,” says sociologist Dominique Méda. “French people are not lazy, they just don’t feel recognized for their work.”

Why French protesters feel ignored on pensions

It’s a frigid February afternoon; just above freezing. But it’s the first sunny day in weeks and there is a palpable energy outside the Paris Opera, where thousands have gathered in protest against the French government’s proposed reform to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64. Raphael Alberto stands in a circle with his co-workers, holding a turquoise union banner.

“Today, the government says [the retirement age] will be 64, tomorrow, they might say it’s 67,” says Mr. Alberto, a junior-high school teacher in nearby Montreuil. “When will it stop?”

Mr. Alberto, like many protesters here, says working conditions have deteriorated in recent years and he’s afraid he won’t be healthy enough to enjoy his retirement by the time he takes it. “We’re one of the last countries to have this system, where we pay for our parents’ retirement and then young people pay for us,” he says. “It’s a true system of solidarity.”

Mr. Alberto, like most French protesters, says he’s fighting to save a sacred – but broken – pension system. But as the government’s retirement reform bill is debated at the National Assembly this month, there is an increasing disconnect between the public and the government about how best to do that.

The government has said that unless the French work longer, the numbers simply don’t add up: Without reform, the pension system will not be able to sustain itself for future generations. And though protesters say this is precisely their main concern, they don’t think working into old age is the right answer.

With one month before the bill is put to a final vote, big questions remain about how to bridge the gap: How can the government inject new life into an ailing system without antagonizing a large swath of the French public? And is it time for the French to rethink their approach to work?

“What French people want is to be heard, that the government addresses their problems. And one of the big problems is working conditions,” says Dominique Méda, a sociologist at the Institute for Interdisciplinary Research in the Social Sciences at Paris Dauphine University – PSL. “The French have high hopes towards work but they’re simply terribly disappointed by it ... and their government. So this [reform] just feels like a provocation.”

A system in need of change

France first put a retirement system in place in 1930, guaranteeing a full pension for those who paid into the system for 30 years. As the decades passed, it went through several iterations, but by the early 1990s, it was in financial trouble.

In 1993, the government launched what became the first of countless reforms. Since then, it has toyed with changing the minimum age or using a points system based on years worked. But the pension system has become central to French citizens’ image of their society.

“The golden years for France came after the Second World War, when the French republic and society functioned relatively well,” says Michel Wieviorka, a French sociologist. “But now, everything from hospitals to schools are deteriorating and people want to defend the things that were acquired during those times, like the retirement system.”

As the French became increasingly attached to their social protections, there was the expectation that the system functioned well. But even though 30 million people pay social contributions to pensions for 16 million retirees, that only pays for 79% of state retirements today. The government has said that due to a rise in life expectancy and the eventual ratio between those paying contributions and retirees, the deficit will reach €1.8 billion ($1.9 billion) this year and €43.9 billion ($46.8 billion) in 2050 without a reform.

According to research by the Retirement Guidance Council (COR), an independent consulting group for the government, these calculations don’t take into account things like inflation and future rising salaries. They say that a more accurate projection, based on GDP, puts the deficit in 2050 at eight times what it is today, versus the government’s 24 times.

Still, there is no doubt that the system is in trouble.

“There are unions saying, let’s focus solely on years worked and not a minimum legal age, but this isn’t what [the reform is] doing,” said Astrid Panosyan-Bouvet, deputy for Paris, member of the social affairs commission focusing on retirement, and member of President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance Party.

“There is a deficit and an urgency that we need to fix [this system] today,” she said, speaking to the Anglo-American Press Association in Paris. “We think it’s a balanced reform and we’re aiming to reach an even better balance by 2030.”

But some have questioned whether the situation is as urgent as the government contends and whether simple math is enough to make up for the missing funds. Vincent Viet, a historian and researcher on social and health policy at the Cermes3 research center, says that because statistically people have more health problems starting at age 60, moving back the retirement age may increase health care costs for workers who would otherwise have left the job market. This could counteract the savings that the reforms are meant to create.

“We should be asking ourselves about the viability of this reform, as well as its impact on and future cost to the health system,” says Mr. Viet. “People are going to get to retirement age in poor health. We need a reform, but we should question whether there are other alternatives.”

The French and work

Indeed, many French protesters worry about not just the daily grind of working extra years, but what this reform will mean in terms of their ability to enjoy retirement. Already, France rates on the low end of the European spectrum when it comes to “disability-free life expectancy” – the number of years lived free of activity limitations due to health problems – at 63.7 years, compared to 74 in Sweden and 70 in Spain, according to 2019 Eurostat research.

Observers say part of that is due to a steady decline in working conditions and an increase in labor inequalities. France has one of the highest levels of accidents at work in Europe and one of the lowest self-reported working conditions, according to a 2021 survey by Eurofound. It takes six generations for someone to move out of poverty here.

So when President Macron said last year that the French worked fewer hours than their European counterparts, it lit a renewed fire among many who felt that the government did not understand their hardships while suggesting a certain ingrained laziness.

According to research from 2021, the French worked less than the OECD average – 1,490 hours per year, compared to 1,716. But some French think tanks have suggested that these numbers only take a macroeconomic approach and ultimately don’t show the full picture, such as how countries calculate things like vacation days and maternity leave.

“In various studies, the French say that work is very important to them, not just the salary but what they get out of it personally,” says Ms. Méda, the sociologist. “French people are not lazy, they just don’t feel recognized for their work.”

France consistently ranks amongst the most productive countries in the world, and in some categories – like part-time work – the French put in more time than the European average.

Those in physically demanding, low-paying, or part-time jobs, in particular, feel unfairly targeted by the reform. Many feel that they shouldn’t have to sacrifice anything else in order for the retirement system to thrive. Rather, they say, the government should replenish the retirement fund by tapping into other accounts, instead of asking for more from an already stretched-thin public.

“Education, health, it all has to cost something, but that’s why we pay taxes,” says protester Stéphane Leguem-Escuriol, an English teacher in a Paris-based vocational school. “We’re more productive [than other countries] but the money doesn’t go back to the people. It’s obviously not going to the right place.”

But such arguments don’t engage with the main problem: All government programs, including the retirement system, are paid for by the public, and the retirement system is getting more expensive.

The government says that it knows it still has work to do. It has admitted to inequities within the reform – such as its repercussions on women – and has promised to address them. Four out of ten workers will still be able to leave earlier if they started earlier in the labor market, according to Ms. Panosyan-Bouvet.

But for the French to feel vindicated – and stop them from continuing regular protest efforts that threaten to shut down the country – they say the government needs to make more than just baby steps toward them.

“I’m not living my life just to get to retirement, but when I get there, I want to be healthy enough to enjoy it,” says Emilie Ducamp, the director of a daycare center in southwest France, who came to the Paris protest with her husband and two young daughters.

“We’re here because we want to show our daughters why people are angry, and to show them that they have a voice. And that together, we have power.”

Patterns

Ukraine war pulls NATO center of gravity eastward

The Ukraine war has reinforced, and reshaped, the NATO alliance. Some less familiar Eastern European players, led by Poland, are coming to the fore.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

A year ago, the trans-Atlantic security alliance, NATO, seemed in disarray; Washington was focused more on China than on Europe, and its European allies were discussing how to lessen their dependence on the United States.

What a difference an invasion of Ukraine makes. And Russia’s aggression has not merely revivified the alliance, it has reshaped it.

President Joe Biden will mark the invasion’s first anniversary in Europe, but not in Berlin or Paris. He will keynote his visit in Warsaw, Poland. That is in recognition of the growing importance that Eastern European countries are assuming, as the center of gravity shifts their way.

France and Germany have provided Ukraine with weapons, but they have done so with some reluctance. Washington’s most reliable shoulder-to-shoulder partners have been on Europe’s eastern flank – Poland and other former Soviet bloc states such as the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, as well as formerly neutral Finland and Sweden, which have chosen to join NATO.

This reconfigured alliance remains a geopolitical work in progress, though, and if Ukrainian forces have difficulty holding back an expected Russian offensive this spring, its unity would be tested.

The former Soviet bloc states would hold firm, but other European governments might seek a path to negotiations. And as the recent balloon scare reminded Washington, China has not gone away.

Ukraine war pulls NATO center of gravity eastward

Like a gusting easterly, Vladimir Putin’s assault on Ukraine has buffeted America and its European allies into huddling more closely together than at any time since the 9/11 terror attacks two decades ago.

Yet the Ukraine war hasn’t just reinforced the trans-Atlantic alliance.

It has been changing it, dramatically.

And while the endpoint of this process isn’t yet clear, the way in which it plays out in the months ahead will have a decisive impact on the war, on the level of Western military support for Ukraine, and the shape of any diplomatic resolution, if and when that comes.

One thing is clear: the U.S.-Europe partnership looks unrecognizably different than before the invasion. And that change will be underscored next week, a year after Mr. Putin unleashed his military in a bid to crush and swallow up Ukraine.

U.S. President Joe Biden will mark that grim anniversary in Europe. But he’ll do so not in Paris, Berlin, London, or Brussels, allied capitals that White House aides would have chosen to keynote a European visit before the Ukraine war.

He will be in Warsaw, alongside the president of Poland, Ukraine’s neighbor and now an increasingly important member of NATO.

On both sides of the Atlantic, that would have been almost unimaginable a year ago – and not just because Polish President Andrzej Duda, like his fellow “illiberal democrat” Viktor Orbán in Hungary, was a full-throated cheerleader for Mr. Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump.

It’s because before Mr. Putin attacked Ukraine, the United States had seemed in trans-Atlantic retreat. Even under a new president, Washington was less focused on its European allies – whom it blindsided with its sudden and chaotic retreat from Afghanistan – than on its rivalry with China.

Europe, too, was in a period of flux, introspection, and uncertainty.

Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, Europe’s elder statesperson, had left the scene, giving way to a coalition under the untested Olaf Scholz. Britain had abandoned decadeslong membership in the European Union and was struggling to figure out how to deliver on the lofty promises of Brexit.

French President Emmanuel Macron, widely viewed as the natural heir to Ms. Merkel, did have a coherent vision, but it was of a more united Europe asserting “strategic autonomy” from Washington, not a closer alliance.

Then Mr. Putin provoked Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War II.

America is now reengaged, as the trans-Atlantic alliance’s indispensable senior partner. It is Washington that has brought the allies together with a unity and effectiveness that very few outside leaders – Mr. Putin surely not among them – would have believed possible.

And while a number of NATO allies have come up with military and financial backing for Ukraine, the United States has been providing by far the lion’s share.

The geopolitics of Europe, too, have changed.

Both France and Germany have given military assistance, including, most recently, tanks and armored vehicles. But they have done so with evident reluctance. In the early months of the war, both Paris and Berlin held out hope of providing some kind of diplomatic exit ramp for Mr. Putin that might bring the fighting to a halt.

Washington’s most reliable shoulder-to-shoulder partners have been on Europe’s eastern flank – Poland and other former Soviet bloc states such as the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, as well as formerly neutral Finland and Sweden, which have chosen to join NATO.

And an unlikely stalwart in Western Europe as well.

Britain has responded with forceful, at times nearly Churchillian, support for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Its own early decision to provide artillery, missiles, and tanks helped prod fellow Western Europeans, especially Germany, to offer more military support themselves.

But while this newly reconfigured alliance has proved staunch so far, it remains a geopolitical work in progress.

Its unity of commitment would be tested particularly if Ukraine’s forces struggled to push back Russia’s expected major new offensive.

The former Soviet bloc states are sure to hold firm. Ever since Mr. Putin’s initial attack on Ukraine in 2014, and his annexation of Crimea, they had been urging both Europe and the United States to take the threat of further Russian aggression more seriously.

And Britain, with uncommon cross-party support, seems resolute in insisting that Mr. Putin must be denied any semblance of victory.

But Russian advances on the ground – or even an increasingly brutal stalemate – might lead other key allies, like Germany and France, to dial back military support and seek a path to negotiations instead.

Washington will hold the key. Mr. Biden has vowed to back Ukraine for “as long as it takes.” But the recent midterm elections handed control of the House of Representatives to the Republicans, and a few members of Congress have begun to question the scale of arms and aid packages.

After the downing of a Chinese surveillance balloon earlier this month, they may seek to make a broader argument: that it’s time to turn America’s attention away from Europe and back to China.

Points of Progress

Cargo ships set sail, and rats sniff out bombs

In our progress roundup, problem-solving includes a nonprofit harnessing animals’ sense of smell to find land mines, shipping companies turning to wind energy, and Bolivians cooperating to protect their source of water, upstream and down.

Cargo ships set sail, and rats sniff out bombs

1. United States

The Super Bowl chose to feature an Indigenous artist for the first time. Born and raised in Phoenix, Lucinda Hinojos is Mexican American and Pascua Yaqui, Chiricahua Apache, White Mountain Apache, and Pima.

Her painting celebrating the event depicts the Vince Lombardi Trophy surrounded by cactuses and hummingbirds, a field of corn, and the White Tank Mountains in the background. The design was used on game tickets and promotional materials.

The NFL’s all-female arts team offered direction but gave Ms. Hinojos creative flexibility. “A lot of people try to put us in a box and stereotype us – that we look this way or we paint this way,” she said. “But with this painting, I combined both my cultures, the Chicano and Native cultures, and I did that with the colors that I used.” Ms. Hinojos also collaborated with other Indigenous artists like Anitra Molina, Carrie Curley, and Eunique Yazzie to create a 9,500-square-foot mural on the Monarch Theatre in downtown Phoenix. And Navajo artist Randy Barton created designs for the interior of the football stadium in Glendale, Arizona.

Sources: ICT News, The Art Insider

2. Bolivia

Bolivia’s city dwellers and rural farmers are cooperating to protect watersheds. What happens upstream affects those downstream. Through reciprocal water agreements, municipalities and fees from urban residents’ water bills contribute to farmers caring for forests and important water sources. These farmers are connected with clean water or other agricultural resources in return. According to the Natura Foundation, which spearheaded the efforts in 2003 and helps fund them, there are now some 24,000 farmers in Bolivia protecting over 500,000 hectares (1.2 million acres) of land in dozens of municipalities, benefiting over 18,000 families. The program is being emulated in Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Mexico.

The strategy is related to the idea of payment for ecosystem services (PES), which has been used in realms from biodiversity conservation to carbon sequestration. PES has also been criticized for promoting the monetization of nature rather than conservation for its own sake. But for participants in Bolivia, the agreement offers peace of mind. “We are all aware that our boliviano is going up there, straight to the water sources,” says Renán Seas, vice president of a water service cooperative. “Otherwise our water supply, which is vital for life, is going to be affected.”

Source: Mongabay

3. Belgium

Rats trained by a Belgian organization are sniffing out land mines. Land mines emit an odor undetectable to humans but easily discerned by the African giant pouched rat. Nonprofit organization Apopo has spent 25 years perfecting the training for its “HeroRATs” to detect explosives buried up to 20 centimeters (8 inches) in the ground. Some 300 rats have taken part in a nine-month certification program and are now detecting land mines in Cambodia, Angola, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

The rats are bred and raised in constant contact with people, making them easy to train and handle. Unlike metal detectors, the creatures know to ignore scrap metal. And while a metal detector could take four days to demine an area the size of a tennis court, trained rats can tackle the job in half an hour. They learn faster, require less food than dogs, and are easier to transport. Rats are not heavy enough to activate most land mines, so no Apopo rats have been injured or killed through their detection work. Apopo rats also detect tuberculosis and are being trained in simulated disaster zones to help find survivors.

Sources: Good, Apopo

4. Holy Land

The first female pastor was ordained in the Holy Land. The Rev. Sally Azar, a Palestinian, will lead the English-speaking Lutheran congregation in Jerusalem and in Beit Sahour, West Bank. Ms. Azar joins four other female pastors ordained in the Middle East – one in Syria and three in Lebanon.

As of 2017, around 47,000 Christians lived in the occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Many are part of the Greek Orthodox and Latin Catholic churches, where women cannot serve as priests. Ms. Azar says she knows it will take time to normalize her role. “I hope that many girls and women will know this is possible and that other women in other churches will join us.”

Sources: BBC, Al Jazeera

World

More cargo ships are harnessing the wind to reduce use of fossil fuels. Shipping generates nearly 3% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions – more than emitted by the country of Germany. Companies are developing new technologies to take advantage of abundant wind power.

French company Airseas offers a massive kite that attaches to ships and flies above the ocean to lower fuel consumption by an average of 20%. Sweden’s AlfaWall Oceanbird boasts upright wing rigs with a flap to take advantage of aerodynamics and function similar to airplane wings.

The innovations offer an unexpected benefit: quiet. “You see dolphins swimming alongside you because they’re not afraid of the engine,” said Jeremy Starn of Sailcargo, a Costa Rica-based clean-shipping company. “It’s a really humbling experience to be connected so closely to nature.”

Source: The Washington Post

Metropolitan museum, behind the velvet ropes

Art has the power to move people out of grief and stagnation. For one author, looking closely and cultivating curiosity brought him to a place of renewal and gratitude.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Barbara Spindel Contributor

Patrick Bringley didn’t set out to work as a guard at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. With a plum post-college job at The New Yorker, he was on an ambitious career track when his older brother, Tom, was diagnosed with cancer.

When Tom died in 2008 at age 26, Bringley, devastated, felt compelled to take a breath, to “drop out of the forward-marching world and spend all day tarrying in an entirely beautiful one.”

As he explores in “All the Beauty in the World,” Bringley finds the Met an extraordinary place in which to grieve, and he is eloquent, if at times wide-eyed, in expressing the ways that art assists him in that process.

He approaches the museum’s vast collection of roughly two million objects with openness and wonder. He is equally curious about its hundreds of guards, who assist and keep eyes on millions of visitors each year. Bringley describes the boredom and discomfort that accompanies the job, as well as the guards’ inside jokes and chatty camaraderie.

Ultimately, “All the Beauty in the World” is about how to look at and appreciate art, a practice Bringley has devoted himself to with earnestness and humility.

Metropolitan museum, behind the velvet ropes

Patrick Bringley spent a decade as a guard at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, but don’t expect any scandalous behind-the-scenes revelations in his appealing and tender memoir, “All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me.” Instead, the author chronicles his personal transformation amid a magnificent collection of galleries watched over by a diverse and genial workforce.

Bringley hadn’t set out to work at the Met. With a plum post-college job at The New Yorker, he was on an ambitious career track when his older brother, Tom, was diagnosed with cancer. When Tom died in 2008 at age 26, Bringley, devastated, felt compelled to take a breath, to “drop out of the forward-marching world and spend all day tarrying in an entirely beautiful one.”

The book captures Tom’s intelligence and playful personality and conveys the magnitude of the author’s loss. Bringley finds the Met an extraordinary place in which to grieve, and he is eloquent, if at times wide-eyed, in expressing the ways that art assists him in that process.

Bringley’s story overflows with wonder, beauty, and the persistence of hope, as he finds not just solace but meaning and inspiration in the masterpieces that surround him.

Perhaps not surprisingly, portrayals of Christ’s crucifixion particularly resonate with the author – and the Met, which was founded in 1870, has plenty of them. Gazing at one, a tempera painting by Fra Angelico, an Italian artist of the early Renaissance, Bringley observes art’s capacity to remind us “that we’re mortal, that we suffer, that bravery in suffering is beautiful, that loss inspires love and lamentation.”

Bringley approaches the museum’s vast collection of roughly two million objects with a similar openness and wonder. (An appendix lists the many pieces cited within the book’s pages.) He is equally curious about its pool of guards, at that time about 400 strong, who assist and keep eyes on an astonishing number of visitors, topping 7 million people in some years. “The glory of so-called unskilled jobs is that people with a fantastic range of skills and backgrounds work them,” he notes, adding that his colleagues are “not only diverse demographically – almost half of the guard corps is foreign born – but diverse along every axis.” The author depicts that heterogeneity in a charming scene: He explains that the Met guards produce an occasional journal of art, poetry, and prose, and he fondly describes its raucous release party, which doubles as an open-mic night, running an eclectic gamut of performances and genres.

Comfortably settled in his museum routine, Bringley is certain that he’ll remain at the Met forever. Training a new guard, Joseph, a middle-aged man from Ghana who becomes a close friend, he gushes about the job. “It would be an indecency, a stupidity, even a betrayal to find fault with such peaceable, honest work,” he writes.

But a lot changes in 10 years. His grief becomes less acute, as grief tends to with time. What’s more, during his tenure at the museum, Bringley marries and becomes a father to two children; his new family further draws him out of his stillness and his sadness. “I no longer need so pristine a setting,” he realizes. “I don’t have to stand on the sidelines, a quiet watchman. I find myself watching parents and children in the galleries and plotting about all that I could do to introduce my kids to the big city and wide world.”

By the time Bringley decides to move on from the Met, we’ve learned a lot about a job that is at once remarkable and unremarkable: the boredom (“Nothing to do and all day to do it,” the guards quip); the discomfort (with shifts of 8 to 12 hours, galleries with wood floors are easier on the feet than those with marble); the inside jokes (it’s apparently not uncommon for visitors to ask where to find the Mona Lisa, which resides not in New York but in Paris, at the Louvre).

“All the Beauty in the World” also offers lessons, drawn from Bringley’s own years of experience, in how to look at and appreciate art, a practice he has devoted himself to with earnestness and humility. After reading this memoir, visitors to the Met or any other museum will likely pay closer attention – not only to the art but to the people watching over it.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A global advocate of integrity checks its own

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For nearly a year, Europe has tried to cope with four surprise shocks. First, Russia violated a European border by invading Ukraine – only to see the Continent rally against it. Then, an energy shock and high inflation hit; both are now mostly under control. The fourth shock, however, has sent Europe into deep soul-searching over its claim to be a champion of universal values in governance.

In December, police in Belgium began to arrest several current and former members of the European Parliament – including a vice president – on charges of corruption and other offenses related to allegations of bribery by Qatar and Morocco. Last month, the parliament’s president, Roberta Metsola, proposed 14 steps to prevent the kind of behavior alleged in the scandal, now dubbed Qatargate.

Meanwhile, the European Commission says it will present a plan in March for an EU-wide ethics enforcer. The EC vice president for values and transparency, Věra Jourová, says that better rules and tough enforcement cannot replace the need for officials to have a conscience. “We should all have some moral compass,” she told parliament. Europe’s soul-searching over the integrity it seeks and espouses has begun.

A global advocate of integrity checks its own

For nearly a year, Europe has tried to cope with four surprise shocks. First, Russia violated a European border by invading Ukraine – only to see the continent rally against it. Then an energy shock and high inflation hit; both are now mostly under control.

The fourth shock, however, has sent Europe into deep soul-searching over its claim to be a champion and an enforcer of universal values in governance.

In December, police in Belgium began to arrest several current and former members of the European Parliament – including a vice president – on charges of corruption and other offenses related to allegations of bribery by Qatar and Morocco. Of the many institutions in the European Union, the 705-member parliament is the only one whose members are elected by the bloc’s 447 million citizens. The arrests have left a reputational taint on European democracy that leaders are quickly trying to fix before elections in 2024.

Last month, the parliament’s president, Roberta Metsola, proposed 14 steps to prevent the kind of behavior alleged in the scandal, now dubbed Qatargate. The measures include tougher rules on gifts and free trips, a “cooling off” period for former members before they can become lobbyists, and an end to “friendship groups” that lawmakers have formed with non-EU countries like Qatar. The parliament will soon take up her proposals.

Meanwhile, the EU’s executive arm, the European Commission, says it will present a plan in March for an EU-wide ethics enforcer. The EC vice president for values and transparency, Věra Jourová, said the proposed entity would investigate and sanction officials who violate rules on conflicts of interest or fail to report assets. According to Transparency International, more than a quarter of parliamentary members have second jobs. Many fail to register gifts they have received.

Ms. Jourová admits that better rules and tough enforcement cannot replace the need for officials to have a conscience. “We should all have some moral compass,” she told parliament members this week in Strasbourg, France.

Europe’s soul-searching over the integrity it seeks and espouses has begun. Or as Jessika Roswall, EU affairs minister for Sweden, told Politico, “We all need to live up to the high expectations and standards when it comes to ethics and transparency.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Living in eternity

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Warren Berckmann

Getting to know our true nature as God’s children empowers us to overcome age-related limitations and brings fresh purpose and vigor to life.

Living in eternity

I was feeling old. I had been slowing down for some time, both mentally and physically, feeling more limited and less interested in activity, in learning, even in life itself. It was as if I were gradually going to sleep. It was subtle, so for a while I didn’t notice it. Then one day I became aware of this trend and recognized it as a challenge to my ability to demonstrate Christ Jesus’ promise of eternal life.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes about this promise in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “‘This is life eternal,’ says Jesus, – is, not shall be; and then he defines everlasting life as a present knowledge of his Father and of himself, – the knowledge of Love, Truth, and Life” (p. 410).

Jesus’ remark was not only a promise but also a statement of the fundamental nature of reality and the eternal relation between God and His children. In the science of mathematics, can numbers come one year and leave the next? Do they eventually wear out or lose value? No! As long as the principle of mathematics exists, so does each number, unchanged and perfect.

This is likewise true of man, whose existence is also inextricably bound to his divine Principle, God. As long as God, the infinite, eternal Principle exists, so do we as God’s image and likeness. And since God has no start or expiration date, neither does His likeness.

Jesus not only revealed the certainty of eternal being but also indicated that eternal life is wholly spiritual, permanent, and ever present. In a deeply compassionate prayer to God for his present and future followers, he stated, “They are not of the world, even as I am not of the world” (John 17:16). And regarding those in need of healing, he promised, “I am come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly” (John 10:10).

As Jesus taught and demonstrated, and as the first chapter of Genesis states, our life has its source in God. In fact, our life is God – Life itself – and is therefore everlasting and always developing. Life is not dependent upon what the ever-limited physical senses mistakenly perceive it to be: bookended by material birth and a transition called death.

Part of the definition of the word “year” in the Glossary of Science and Health illustrates our ability to understand and demonstrate this fact: “One moment of divine consciousness, or the spiritual understanding of Life and Love, is a foretaste of eternity. This exalted view, obtained and retained when the Science of being is understood, would bridge over with life discerned spiritually the interval of death, and man would be in the full consciousness of his immortality and eternal harmony, where sin, sickness, and death are unknown” (p. 598).

While praying about this, I began to grasp the significance of life without interruption, reflecting divine Life, God. And this spiritual perspective woke me from the mistaken sense of having two lives – an earthly one here and now that is limited, physical, beginning and ending, and another one later that is spiritual, continuous, and unlimited.

The material sense of a limited life winding down would mesmerize us into accepting declining activity, diminishing interests, and a deadening of vitality. But we can all come to understand that we are already spiritual. We are already living in the kingdom of heaven, even though it doesn’t seem that way to the physical senses.

Inspired by this answer to prayer, I daily claimed eternal Life as the reality. I also strove to adhere to God’s requirements. For instance, when a man asked Jesus how to “inherit eternal life” (see Luke 10:25-28), Jesus referred him to the need for obedience to the commandments, specifically, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind; and thy neighbour as thyself.”

Taking these steps daily led me to new energy, a renewed sense of purpose, greater joy, and expansive and fulfilling activity. Gone were the pervading sense of growing old and the effects that I had been experiencing.

We aren’t destined to try to make a material life more spiritual. Our task is to repudiate material life and strive to demonstrate eternal life right where we are. Turning to our heavenly Parent in this work kindles within us an awareness of, and a capacity to demonstrate, our native spiritual identity in a God-centered universe, where all is eternal harmony.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Feb. 13, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Sacred space

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow for a conversation with our Scott Peterson, who brings humility, respect, and sensitivity to his reporting from conflict zones like Ukraine and Somalia.