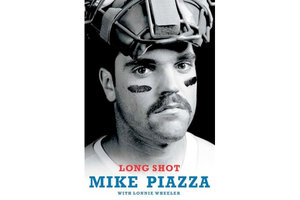

Long Shot

In 'Long Shot,' 12-time all-star Mike Piazza recounts his unlikely path from suburban Philadelphia to the big leagues and even how it led to a trip to the Vatican.

Long Shot

By Mike Piazza and Lonnie Wheeler

Simon & Schuster

384 pp.

Surely Mike Piazza is the only baseball player who has done all of the following: met the pope, had Ted Williams visit his backyard batting cage, assisted the Italian baseball federation, and hit a memorable post-9/11 home run in New York City. Piazza also is probably the greatest hitting catcher of all-time. Yes, better than Yogi Berra and Johnny Bench. He makes his case with a .308 lifetime batting average and 427 home runs, the most ever by a big-league catcher.

On the surface, then, he would seem a lock for the Hall of Fame. But there aren’t any surefire inductees among modern sluggers, all of whom confront suspicions, founded and unfounded, about possible drug use.

In Long Shot, Piazza vehemently denies having ever taken performance-enhancing drugs while acknowledging his use of all sorts of dietary supplements. The Hall of Fame balloting for this year’s class, the first for which he was eligible, suggests that most voters take him at his word and recognize his playing credentials. Although he didn’t receive 75 percent of the votes required for election, he did get 57.8 percent compared with only 36.2 percent for Barry Bonds and 16.9 percent for holdover candidate Mark McGwire. And it wouldn’t be surprising to see him do better in future elections as some voters, reluctant to usher in a first-year candidate, may be more inclined to reconsider Pizza’s track record.

Piazza certainly believes he belongs among the all-time greats, even if his fielding wasn’t the equal of his hitting and he struggled at times to throw out base stealers. Making the hall, he grants, would be much-desired validation of his achievements in baseball, which in retrospect seem such a long shot, thus the title of his autobiography written with Lonnie Wheeler.

Growing up in the Philadelphia suburb of Phoenixville, Piazza was a good player in high school but not destined for stardom. He did, however, have three things going for him: a tremendous desire and work ethic to play and improve; a dad who was over-the-top in pushing and promoting his son’s career; and a very valuable major-league connection in the form of his father’s close friend and fellow Norristown, Pa., native, Tommy Lasorda, who managed the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1976 to 1996.

When Piazza was 16, the Dodger connection led Ted Williams, who was appearing at a trading card show in King of Prussia, Pa., to drop by the Piazza home to see “Vince’s kid” take his backyard practice swings against a JUGS pitching machine. Williams urged him to stay back and wait on pitches and concluded that “hitting’s going to be his big suit.”

But despite Piazza’s countless rips at mechanical deliveries and efforts to build hand strength by crushing Tastykakes boxes, scouts had doubts about his ability to hit live pitching and his slow foot speed.

Only via a special tryout arranged while he served as the Dodgers teenage batboy one summer did he get an offer to play college ball at the University of Miami, where an assistant coach labeled him a “five o’clock hitter” – a guy whose most impressive hitting occurred in pregame batting practice. Piazza eventually switched to Miami-Dade Community College.

With his prospects for a professional career looking bleak, Lasorda intervened and ordered the Dodgers to make Piazza a courtesy draft pick – on the 62nd round of the 1988 draft. That meant he was the 1,390th player chosen.

The club had never seen him play a game and didn’t really have plans for Piazza until his dad leaned on Lasorda. Thereafter his dad paid for him to fly to L.A. for a private workout, in which Piazza crushed 20 or so balls out of the park. This started him up the ladder via experiences in the Instructional League and a stint as the first American player to spend time at the Dodgers’ winter camp in the Dominican Republic.

A fast learner, Piazza “arrived in heaven” in 1989 when he made his first appearance at Dodgertown, the franchise’s famed spring training camp, then located in Vero Beach, Fla. When opportunity finally knocked to join the parent club, he wasted no time in making his mark. As the National League Rookie of the Year in 1993 he batted .318 with 35 homers and 112 runs batted in. He also made that year’s NL All-Star Game roster, the first of 10 consecutive selections and 12 over his 16-year career.

Piazza played eight years for the Dodgers, but two acrimonious contract negotiations soured him on the organization. When things broke down the second time, he was dealt to the Florida Marlins. After only five games, he was acquired by the New York Mets.

Although subjected to what he called “serial booing” by fans early on, he eventually felt more appreciated playing in New York than he did in Los Angeles. As a result, if he’s ever voted into the Hall of Fame, he hopes to go in as a Met. (The folks who run the Cooperstown, N.Y., shrine make that call, but players are free to voice their preference.)

It was during his years with the Mets that Piazza married and also made his first trip to Europe as part of a Major League Baseball goodwill tour to visit baseball academies in London, Berlin, and Rome. While in Italy, the national sports council arranged for him to join a large papal audience at the Vatican. He was among the VIPs that day who actually were introduced to Pope John Paul II. He left behind a “Piazza, 31" Mets jersey for the pontiff.

Piazza later would suit up for the Italian national team in the first World Baseball Classic. Through his association’s with his grandfather’s homeland, he has decided to pursue becoming a dual citizen of both the US and Italy.

As for playing in the World Series, Piazza only managed to do that once, but it was eventful for two reasons. In 2000, the Mets squared off against the Yankees in the city’s first “Subway Series” since 1956 when the Yankees beat the Brooklyn Dodgers. It promised melodrama as Piazza strode to the plate against Roger Clemens, who had beaned him during a regular-season interleague game earlier that year. The New York media had a field day playing up the rematch angle, then had lots more to write about when, in trying to fight off an inside fastball in Game 2, Piazza’s bat broke apart in two places.

Piazza began running to first until he realized it was a foul ball. Clemens, meanwhile, fielded a piece of the bat and threw it in Piazza’s direction, causing both teams to come onto the field. After order was restored, Piazza grounded out. He later hit a home run off reliever Jeff Nelson, but Clemens and the Yankees got the win, and went on to take the Series in five games.

If that was a disappointment, his New York years ago produced one of his finest hours and what was named the second-greatest moment in Shea Stadium history, behind only clinching the 1986 World Series. In the first game played in Shea after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, feeling especially determined and patriotic, Piazza came through with a game-winning homer to center field in the eighth inning to beat Mets nemesis, Atlanta,

Piazza remembers feeling the eruption of crowd noise might crumble the stadium. “It was a moment for New Yorkers ... to let it all out at last, whatever they felt,” he writes. “To scream, to cheer, to chant, to hug, to cry, to jump up and down in celebration of something happy again, something normal and familiar and fun again; of getting their lives back, at least in some small way.”