Mary Oliver looked 'past reason, past the provable'

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and essayist wrote lyrically about nature, but there's more to her work than meets the eye.

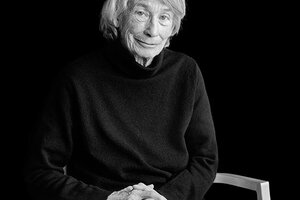

Poet Mary Oliver

Courtesy of Mariana Cook/The Penguin Press

Critic V.S. Pritchett once remarked of Simone de Beauvoir that she “is one of those writers who dig and dig until they pile up the monumental.”

It points to the way that some writers yield their insights slowly and incrementally, creating a body of work eventually revealed as something grand.

That thought came to mind with the recent death of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Mary Oliver. Oliver’s poetry collections tended to be slim and light – so slender that when I bought a couple of them on summer vacation a few years ago, they barely registered a presence in my knapsack.

The books proved a perfect companion for the flight back – a comforting reminder that even as I was returning home to humdrum routines, her poetry would continue to provide a sense of departure.

Many of Oliver’s other fans also seemed to like how her work, like any good poetry, took them out of themselves for a while, setting the world at an arm’s length that allowed it to be seen more clearly. That led critics to mistakenly assume that both Oliver and her admirers were simply indulging in escapism, lost in the landscape of the New England woods that Oliver often liked to write about.

But as I suggested in a 2017 review of “Devotions,” a collection that assembled her best poems, Oliver’s writing was about engagement, not escape. She wasn’t turning her back on the so-called real world, as we like to call the universe of white noise we walk through every day, navigating cable news, celebrity gossip, the din of traffic. Oliver was, instead, nudging us to acknowledge that the real world might, indeed, be exactly the one that appeared in her poems: the rocks and trees, herons and frogs, dogs and earth that constitute humanity’s ancestral home.

As I also noted, “Devotions,” at 400 pages, was a testament to the scale of Oliver’s achievement. Her poems, appearing in feather-light collections over the years, might have tricked fans and detractors alike into thinking that her work was light, too. But “Devotions” –bigger, heavier, a great summing up – affirmed an abiding and overlooked reality of Oliver’s poetry. Her poems, we now realize, had gravity. They were, to be sure, touched by lyricism, humor, an unabashed sense of wonder. But that wonder was grounded in an acute sense of life’s mysteries – many of them beautiful, others incalculably dark. In “After Reading Lucretius, I Go to the Pond,” she sees a heron eat a frog, admiring them both. Such poems expressed her abiding awareness that beauty and loss often kept close company.

That truth informed Oliver’s fine essays, too. In “Bird,” a selection from her 2016 collection, “Upstream,” Oliver recalls bringing home a wounded gull, eventually wondering if her “rescue” has simply prolonged the pain of a doomed animal while allowing her to enjoy a false sense of virtue.

Oliver’s poems and essays, which could seem simple and pleasant while resonating with complicated themes, invited comparisons with Robert Frost, another ostensibly “accessible” poet who, on second reading, offers more than initially meets the eye.

“Knowledge has entertained me and it has shaped me and it has failed me,” she wrote in another essay, “Winter Hours.” “Something in me still starves. In what is probably the most serious inquiry of my life, I have begun to look past reason, past the provable, in other directions. Now I think there is only one subject worth my attention and that is the precognition of the spiritual side of the world and, within this recognition, the condition of my own spiritual state. I am not talking about having faith necessarily, although one hopes to. What I mean by spirituality is not theology, but attitude.”

That sense of the unknowable rests at the center of Oliver’s poems, not as a rebuke but an invitation. The invitation still stands for Mary Oliver’s many readers, a sustaining comfort now that she’s gone.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Baton Rouge Advocate, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”