‘Goodnight Moon’: 75 years in the great green room

Generations of children have been lulled to sleep by Margaret Wise Brown’s bedtime story, with illustrations by Clement Hurd, first published in 1947.

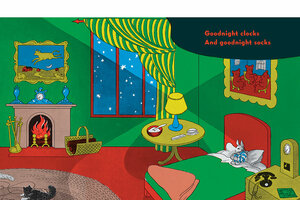

Clement Hurd/Used with permission of HarperCollins Children's Books

When Kenny Varner attended the 60th birthday party of a family member recently, he was somewhat startled after the conversation turned to the enduring appeal of “Goodnight Moon.”

He had mentioned how the much-beloved children’s bedtime story by Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd would turn 75 in September. Dr. Varner, who directs the Gayle A. Zeiter Literacy Development Center at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, had been thinking about the reasons “Goodnight Moon” is as popular today as it was decades ago.

“We pulled it up on our phones, and we’re looking at a digital version of it together, and it’s just a text that is really robust,” says Dr. Varner, who focuses on literacy, language, and cultural identity. “And then family members and other folks, from the ages of 5 to over 90, all began to share memories of the importance of this book, both in their own childhoods and now and with who they are as parents. So there’s this interesting intergenerational thing happening with ‘Goodnight Moon,’” he says.

Why We Wrote This

There’s nothing quite as delightful as curling up with a young child and a bedtime story. For 75 years, millions of families have found everyday joy by reading Margaret Wise Brown’s classic “Goodnight Moon” together.

Indeed, for generations this book about a great green room with a telephone and red balloon has been a part of millions of bedtime rituals, making Dr. Varner and others marvel at the aesthetic and developmental power that continues to make it a family favorite.

The playful language excited the 5-year-old at Dr. Varner’s family gathering – the kittens, the mittens, the bowl full of mush! The person over 90 recalled, too, how the black-and-white prints interspersed in a book about a “great green room” were actually meant to keep costs down. Color prints could make a picture book prohibitively expensive back then.

“But that, actually, that’s one of the most memorable features of the book,” says Dr. Varner. It creates an aesthetic rhythm, melding perspectives of time, blinking back and forth between modern color and familiar black and white – even as time is grounded in subtle visual details, like the clocks, which move forward 10 minutes through the frames, and the moon, which rises bit by bit behind the window.

“A small child is able to experience a comforting, structured routine without a deep, complex storyline,” Dr. Varner says.

But when “Goodnight Moon” was first published in 1947, such techniques were both innovative and radical, says Cara Byrne, professor of English at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. A scholar who focuses on the history of children’s storybooks, she begins all of her classes each semester with a discussion of the popular bedtime classic.

“‘Goodnight Moon’ is actually a really great book to bring in first, because at its time it was doing something really radical,” says Dr. Byrne. “Her books were part of a movement of educators who were trying to push away from some other, older models of educating children – other norms or ideas about children as needing a particular type of instruction, needing to be moralized in a particular way.”

Indeed, in 1935, Ms. Brown studied to be a teacher at Bank Street College of Education, the alternative teacher training school in New York’s Greenwich Village. Its founder, Lucy Sprague Mitchell, believed children needed stories anchored in the familiar rather than the fantastic – and grounded in empirical research about the psychologies of children as they interacted with their worlds.

Ms. Brown never finished her studies or became a teacher, but as she began to write storybooks she moved away from the kinds of traditional folk tales and fables that conveyed simple moral messages. Instead, she wrote stories about the preoccupations of children, their curiosities and emotions and fears.

She also sought out illustrators more in tune with modernist and avant-garde visual sensibilities. Mr. Hurd’s illustrations in “Goodnight Moon,” many have observed, are similar to Henri Matisse’s “L’Atelier Rouge.” The illustrations in “The Runaway Bunny” could have been inspired by Georges Seurat’s “The Circus.”

“I think it’s one of those beautiful books that not only was revolutionary in its time; it was also kept out of some library collections because it was so different and odd,” says Dr. Byrne.

One of the book’s detractors was Anne Carroll Moore, the influential head of the children’s wing at the New York Public Library. A major historical figure and innovator in her own right, Miss Moore practically invented the idea of having a children’s wing in libraries. She introduced storytelling hours to NYPL’s vaunted main branch and instituted policies to allow even the poorest of immigrant children to check out books.

Persnickety and traditional, Miss Moore was also in many ways a powerful foil to Bank Street’s radical new ideas about childhood development and storytelling. A staunch proponent of magical, fantastic tales with plots upholding a moral order, she was enthusiastic about the stories of Hans Christian Andersen and Beatrix Potter while famously disliking E.B. White’s classic children’s stories “Stuart Little” and “Charlotte’s Web.”

Similarly, the powerful New York librarian thought little of Ms. Brown’s storytelling, and because of her influence, “Goodnight Moon” was kept off shelves until 1972, the year of its 25th anniversary, when it was selling almost 100,000 copies a year.

Mike Scott, a writer and communications specialist in Cleveland, has been reading “Goodnight Moon” and other books by Ms. Brown to his kids and grandkids for over 35 years.

“For me, ‘Goodnight Moon’ is a weirdly sweet book, and I always enjoyed the poetic rhythm,” says Mr. Scott, who read the book to his adult children decades ago and is now again to his 3-year-old son, Ulysses, whose nickname is Ulee.

“But it’s also a book with some very unexpected things in it. ‘What’s that mouse doing in the middle of the room? Who keeps a bowl of mush next to their bed? And what is mush, anyway?’”

These are the questions he asks each generation of his family, and they respond to the book’s quirky hilarity as well as to the overall warmth of the book, he says. “It’s a fun book. Reading it is like going back into time, but sort of sideways and landing into an odd room, indeed.”

Ulee now loves the story – it’s one of his favorites, Mr. Scott says. They shared a special moment recently, too, when Ulee was excited to notice that the painting hanging on the left wall of the great green room – a black-and-white sketch – was actually a scene from “The Runaway Bunny,” another Margaret Wise Brown story they read together.

“It was a pretty cool moment when we made that connection,” says Mr. Scott.