How my grandfather was like Michelle Obama’s

They were ordinary Black men, working to make a better life for their families, despite racism.

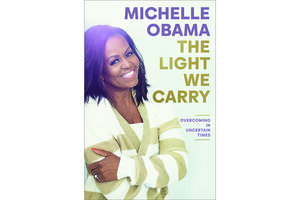

“The Light We Carry,” by Michelle Obama, Crown, 335 pp.

I keep coming back to Michelle Obama’s “The Light We Carry: Overcoming in Uncertain Times” because it speaks to something deep inside me. While Mrs. Obama shows the same willingness to tell her truth as she did in her 2019 bestselling memoir “Becoming,” she is most powerful, most relatable, when she shines her light on the contributions of ordinary Black men.

The accomplishments of these men can so often be obscured (and understandably so) by the trauma represented by a Trayvon Martin or a George Floyd. But Mrs. Obama’s book highlights another, sometimes overlooked aspect of being Black in America – our ability to gain strength and move on.

She does this by first talking about her father, Fraser Robinson, who struggled with multiple sclerosis and still went to work each day to support his family. She speaks movingly about the cane he used and the symbol it became of lurking instability in her otherwise remarkably loving and stable family.

“MS was undermining his body ... as he went about his everyday business: working at the city’s water filtration plant, running a household with my mom, trying to raise good kids,” she writes.

One cannot help but admire this man because, in a sense, he is Everyman. At least every good man.

But what I loved most about the book was the strong beam she shines on her two grandfathers, nicknamed Southside and Dandy, and the men of their generation.

It makes me think of my own grandfather who escaped a Jim Crow state looking for a better life in Kansas City, Missouri. He’d settled there after returning from a world war in which he had fought against fascists and Nazis when, effectively, he did not have the right to vote in his home state of Oklahoma. He’d been filled with optimism – at least this is what I’ve been told – but he discovered that crossing the Mason-Dixon Line was no panacea. He, along with Mrs. Obama’s grandfathers, discovered that moving to the North was no guarantee of equality.

Mrs. Obama is quite cleareyed about this. She writes, “I felt a little bound and a little provoked by the legacy of my two grandfathers, proud Black men who had worked hard and taken good care of their families but whose lives had been circumscribed by fear – often tangible and legitimate fear – and whose worlds were narrowed as a result.”

My grandfather, like hers, only felt safe when he was cocooned within his community, his church, his beloved family. Being in the wrong neighborhood could get a Black man in serious trouble. (Unfortunately, that is just as true now as it was then.) Mrs. Obama tells of the day when Dandy gave her a ride to a doctor’s appointment when she was a teenager, because her mother was at work. He picked her up “dressed up for an outing and full of the same bluster and pride he always had when we visited him at his apartment. It wasn’t until we started driving toward downtown that I noticed his clenched jaw and tight grip on the steering wheel,” she writes.

As young as she was, she realized that her grandfather was frightened – petrified really – of being on an unfamiliar mission in an unknown part of town.

Like hers, my grandfather was shut out of stable, trade union jobs because he was Black. After the war, he worked in construction. When Black laborers, who were often given the most dangerous jobs, organized their own union and went on strike to be paid on parity with white construction workers, the white union workers crossed the picket line and the strike was quickly broken.

My grandfather, like Mrs. Obama’s grandfathers, didn’t complain. He did what he had to do. He went to work as a mail sorter at the post office. The strike had been a rough time and he was grateful for the job – where he worked alongside white people. But I can never recall one white person in his house. Never one who came to his door. Never even saw him talk to one. What he thought of them remains a mystery.

And yet I am so grateful to him. His determination to hold on to his dignity, to not knuckle under, marked a pathway for our family to move forward, to expand on what he’d not been allowed to do. I’m grateful to my grandfather – and to Mrs. Obama’s grandfathers – for doing this. And I’m thankful to her for reminding us that they did.