‘The Fraud’ pokes at Victorian-era biases – and our own

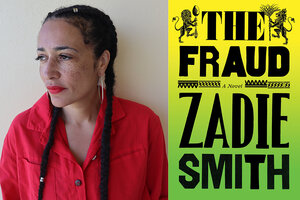

Zadie Smith is the author of "The Fraud."

Ben Bailey-Smith

Zadie Smith turns her sharp eye to historical fiction in “The Fraud,” which centers on a notorious 1870s trial of an Australian butcher who claimed to be Sir Roger Tichborne. Sir Roger was heir to a family fortune in England, and he was thought to have been lost in a shipwreck years earlier. At stake in this novel, which is drawn from actual events, is not just the Tichborne family wealth, but also the matter of identity. “Who are we?” is a question that underlies much of Smith’s work, beginning with “White Teeth,” her spectacular 2000 debut.

Smith deftly weaves rich source material, including trial transcripts, into a lively though never straightforward narrative, making it clear why she was drawn to this Victorian-era cause célèbre. One of the documents she quotes, by the defending attorney’s daughter, characterizes the mania that ensued over the case as “a species of moral tornado” that “excited every sort of human passion.”

Smith puts her bemused imprint on the proceedings. “The Fraud” encompasses issues of class, bias, race, and money as “a material form of freedom,” how we separate truth from falsehood, and what we can really know about other people.

Why We Wrote This

Amid rising concerns about disinformation and bias, Zadie Smith’s colorful and historical characters shed light on the roots of our biases.

In a brilliant move, “The Fraud” is told largely from the close third-person viewpoint of Eliza Touchet, an uncommonly strong, sharp-tongued observer. Widowed early after a miserable marriage, Eliza became a housekeeper and housemate for her cousin, William Harrison Ainsworth, a prolific, popular mid-19th century novelist whose friends included William Thackeray, George Cruikshank, and Charles Dickens.

Ainsworth (1805-1882) published 41 books in his lifetime – none of which remain in print. His most famous, the sensational 1839 crime novel, “Jack Sheppard,” actually outsold Dickens’ “Oliver Twist” – until the murder of an aging aristocrat in 1840, thought to be a copycat crime, raised questions about the damaging influence of violent entertainment. (Claire Harman reconsiders the case in “Murder by the Book: The Crime That Shocked Dickens’s London,” published in 2019.)

Eliza is a wonderfully vivid and, in many ways, modern character, certainly not your stereotypical Victorian. Bisexual, fervently abolitionist, and a “natural cynic” with strong misgivings about the source of much of England’s wealth, she is a single woman who craves independence more than anything else.

Smith clearly has fun fleshing out what little is known about Eliza’s relationship with her cousin. William, an uncommonly sweet and submissive man, was “constitutionally unable to disappoint anyone,” she writes. But, she adds, “No one had ever accused William of being backward about putting himself forward.”

Eliza considers most of William’s fiction, set in the distant past, unreadable nonsense, including his latest “Jamaican novel,” set in a place he knows nothing about. She wonders why William doesn’t focus on contemporary stories, like George Eliot does. Smith has a fine time quoting and satirizing Ainsworth’s work, filled with laughable lines like “‘Zounds!’ he mentally ejaculated.”

“The Fraud” jogs back and forth – sometimes confusingly – between the 1830s and the 1860s. In the early years, after the death of William’s first wife, Eliza was the de facto lady of the house, hosting dinners for William’s eminent literary colleagues. In the 1860s, she is displaced by Sarah Wells, an illiterate former maid who becomes the second Mrs. Ainsworth after bearing her boss, nearly 40 years her senior, a daughter. At first reluctantly, Eliza accompanies Sarah, who is besotted with the Tichborne case, to the trial.

Ever the critic, Eliza finds the proceedings overstuffed with too much irrelevant information, “like reading a novel by William.” And, although embarrassed by the uneducated girl’s excited whoops during the spectacle, she comes to recognize the astuteness of some of Sarah’s primal reactions.

Eliza is so deeply impressed (if not entirely swayed) by the dignified, unswerving testimony for the defense by Andrew Bogle, the formerly enslaved longtime manservant of the late Baron Tichborne, that she takes him to tea. His family’s story, rife with the horrific realities of slavery in Jamaica, is embedded in the second half of “The Fraud,” spanning nearly 100 powerful pages.

This isn’t the first time Smith has found inspiration in British literature and woven a variety of auxiliary documents into her fiction. Her third novel, “On Beauty” (2005), used E.M. Forster’s Edwardian masterpiece, “Howards End,” as a template for an exploration of privileged people’s responsibility to share their advantages with the less fortunate. She touches on some of these moral issues again in “The Fraud.”

But what makes Smith’s latest novel so compelling is the way Eliza grapples not just with the suggestibility of most people, “with brains like sieves through which the truth falls,” but also with her own biases and limitations, such as her “tendency to believe what she most needed to be true.” Her determination to be “gentle and mindful of Sarah’s hurt feelings, always remembering that false beliefs are precisely the ones we tend to cling to most strongly,” is one of many aspects of “The Fraud” that bears particular resonance today.