The problem with the word ‘suffrage’: It excludes Black women activists

Historian Martha S. Jones answers questions about the political history of Black women in America and their collective struggle for voting rights.

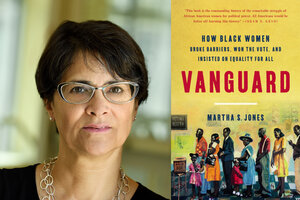

Historian Martha S. Jones' book “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All,” is expected to be published on Sept. 8 by Basic Books.

Will Kirk/Courtesy Johns Hopkins University

Martha S. Jones is a historian, an author, and a professor at Johns Hopkins University. In her book “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All,” expected to be published Sept. 8, she explores the complex political history of Black women in America and their collective struggle for voting rights. She spoke with the Monitor about her latest project, the problem with the term “suffrage,” and the importance of just doing the work.

Q: What was the most interesting part of your research for “Vanguard”?

You know, something that I’ve come to really cringe about – you have to forgive me – is the word “suffrage.” Every time we say it, we’re really invoking a very particular and very white middle-class political movement that led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. However, it is not a term that captures the wholeness of African American women’s political activism or aspirations or visions. I use the phrase “voting rights” instead.

There’s no way I will be able to extinguish the word “suffrage” through my conversations this year. But I learned what a loaded framing that is for thinking about women’s political power and how it carries with it a set of assumptions that Black women are on the margins.

Q: Black women were erased from the suffrage movement, from #MeToo, and in a way, from the Black Lives Matter movement. #SayHerName was meant to specifically honor the lives of Black women. Why does this type of exclusion keep happening?

From my work, I would say that it requires our sustained vigilance. It also requires our courage, to be our own witnesses. I do think that it matters who is in charge, who holds the office, who sets the agenda. Black women need to have an opportunity to speak about our political agenda, which includes a history of sexual violence along with many other issues [such as police brutality] that are likely more familiar to our community. Really, from the origin of Black women’s political consciousness, there is an urgency to the issue of sexual violence. And we learn this through the testimony of enslaved women, like Harriet Jacobs, who pens her memoir in 1861 and gives voice to the fact that sexual predation ran through the lives of enslaved women. Then it comes all the way forward to Tarana Burke’s #MeToo movement.

Q: Do you explore that particular history in your book?

With the women that I write about – and it’s 200 years of Black women’s political history – part of what I was struck by was the way nearly every woman tells a story of either being the victim of sexual violence or living under the threat of sexual violence. Yet we don’t claim that as an essential concern or central facet of our political objectives. Rape was a central instrument of violence and terror during the era of enslavement.

Q: Do you think that history is a vicious cycle or are we actually going to change policing this time?

There’s something to be said about the inevitability of change and the inevitability in any historical moment of the battle between good and evil.

Yes, we will move through change. Some of it may even be laudable and slowly eat away at the scourge of white supremacy and anti-Black racism. But we will still live in a country where we, by necessity, have to be vigilant in the fight against all kinds of injustice, inequality, and xenophobic racism – even if somehow Black Americans are no longer the first target of that kind of evil.

Q: How do you stay hopeful at this particular moment in America?

For me, hope derives from being in the work. I’m a teacher, I’m a historian of the Black experience, I’m a writer. I find pieces of hope every day, whether it’s one of my students having a revelation or when I’ve written something and it speaks to someone. That’s one answer.

On the wall of my home office hangs a portrait of my great, great, great grandmother, Nancy Belgraves, who was born in 1808, enslaved, in Danville, Kentucky.

Q: How does she inspire you?

She watches me work every day. She has a lot to say in my mind and one of the things is: “I survived for a reason. I survived for a purpose.”

What gives me purpose is knowing that she survived so that I would be here to do the work in my own lifetime. I keep her picture right there so that I don’t forget that.