Q&A with N. Scott Momaday, author of ‘Earth Keeper’

Pulitzer prize-winning writer N. Scott Momaday discusses his newest book, his life, poetry, and his career.

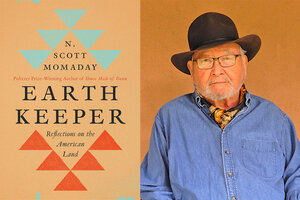

Author N. Scott Momaday appears with his book, “Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land.”

HarperCollins Publishers

Poet, novelist, and essayist N. Scott Momaday led the renaissance of Native American writing when his first novel, “House Made of Dawn,” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1969. He says his latest book, “Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land,” is a summation of many of the themes that are woven through all of his writings. He spoke with Monitor correspondent David Conrads about the book, his life, and his career from his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Q: What was the inspiration behind “Earth Keeper”?

I have long been interested in ecology and the preservation of the landscape. I have a natural investment in the landscape through my ancestry. It’s something that I think about quite often and have for a long time. So I finally put it down in this book. I think of “Earth Keeper” as a kind of spiritual guide, a handbook of reflections on the essential nature of the earth.

Q: You write that we have failed to recognize the “spiritual life of the earth.” What do you mean by that?

With the industrial revolution we have lost sight of the land and lost the sense of its spirituality. The Native American preserves that, in a way, and has a deeper understanding of the earth, having been on the North American continent for thousands of years, and has developed a kind of an attitude and a reverence for the land. I inherit that and I’m very grateful for that. It’s been a principal subject of my writing and will continue to be.

Q: Do you see any remedy for this failure?

I think that we’re being pushed to a greater awareness of the importance of preserving the earth and developing a spiritual attitude towards it. I think climate change is going to be responsible, in part, for the return to the land. At least, that’s my hope. I think it’s critical. We face the destruction of ourselves, as well as the earth, by our indifference towards the land. We rape the land. We think it’s something to be exploited. I think that’s not the right idea. It’s something to be revered and protected.

Q: How has your Kiowa heritage impacted your writing?

It’s been crucial. I’m very much aware of that background and I write out of it. I have a great respect for my ancestry and what it means, that Native people came to this continent thousands of years ago and have developed a kind of conservation attitude towards the land. Not simply for the sake of preserving landscapes, but also an awareness of the deeper meaning of the land. We need to rely on science, but before anything, we need to understand that the earth is possessed of spirit. We can’t save the earth without it.

Q: You write in “The Death of Sitting Bear,” which was published earlier this year, that poetry is “the highest form of verbal expression.” Why?

Because poetry is the best possible way of saying something. It is the highest achievement of language. It’s precise. It makes no room for extraneous matter. It has to be carefully measured. That’s the definition of poetry. That is, it’s composed of verse and verse is measure. That’s a very high form of expression. The highest, I think.

Q: How does that square with your regard for the Kiowa oral tradition, which does not include poetry?

That’s true. There’s no such thing as poetry in Native American language, strictly speaking. There is something poetic, of course, in the oral tradition that makes use of rhythms and sounds. It’s a highly poetic kind of language, but it is not poetry as we define that term. Poetry, to my understanding, is a statement concerning the human condition composed in verse. That’s exclusive. There’s nothing like it in Native American oral tradition, but there is a strong sensitivity to language and the sound of language and the meaning of language in the Native oral tradition. So it is not poetry, as such, but it is poetic and that’s primarily what influenced my writing.