Giving Black women in pop music their due: Q&A with author of ‘Shine Bright’

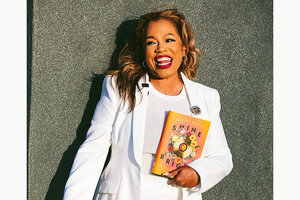

Danyel Smith wrote the memoir "Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop."

Jennifer Johnson/One World/Roc Lit 101

Journalist Danyel Smith is determined to claim the rightful place of Black women in pop music. It’s a subject she knows inside out, as both a cultural critic and a self-described super fan. She uses her voice to uplift and celebrate the women whose histories and careers typically started with less wealth and opportunity than those of white pop stars.

Her tenacity has led her to create and produce the podcast “Black Girl Songbook.” Her career has included stints as a senior producer at ESPN and editor at Billboard, Time Inc., and Vibe. She also has two novels to her credit: “More Like Wrestling” and “Bliss.”

Her latest book is as much a memoir as it is an appreciation for Black women in music. “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop” weaves together Ms. Smith’s upbringing in Oakland, California, with the childhoods of icons such as Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, and Mariah Carey.

Why We Wrote This

Motivated by a determination to set the record straight, journalist and author Danyel Smith stakes a claim for the pivotal role of Black women in pop music.

She spoke recently with the Monitor about her determination to set the record straight, her commitment to journalism and advocacy, and how Black women are the linchpin of pop music.

What inspired you to write the book?

I don’t know if I wanted to write it as much as I felt there were things that needed to be said. There are many things in the world of music, journalism, and music criticism that are written around, and I wanted to approach them directly, particularly in regard to Black women in pop music.

It began to feel like a pull, like a duty to create the book; it was similar to the pulls that I felt working in editorial and working for publications like Vibe. Over the course of my career, it feels like I’ve been in service to the culture in one way or another. That’s a long way of saying that “Shine Bright” is a service to the culture and I feel called to it.

You’re speaking about service through reporting, but also advocacy. Can you talk about that?

So often, what gets attached to the idea of advocacy is that somehow you are not being fair to all parties, or that you are somehow biased toward one group. I just don’t think that is true. Advocacy means I have a familiarity with the culture, the context, the characters, the situations, and the history.

What that means for me is I know just how much of all of that has been overlooked with regard to Black people and in particular Black women. I felt very similarly about the art of hip-hop. When I first got into my career, everyone – and by everyone I mean the mainstream media and culture – was referring to hip-hop as a fad. It wasn’t a “real art form.” It was “terrible.” Everybody was going to go downhill into hell immediately because of the sound of the music. I knew that not to be true. I knew the power of rap almost from its beginnings. I had an inkling of what was to come based on the history of the music that Black people create, whether it’s rhythm and blues, jazz, soul, or pop, we continue to create things that influence global culture.

So it didn’t take a genius to realize that’s what was coming with rap. I also just knew experientially how it was making me as a Black woman feel. So I don’t think that advocacy is a bad word. I feel like advocacy is a banner of truth and it’s getting to what’s actually real. And yes, I have practiced [advocacy] as often as I can, I practice it now, I practiced it then, and I will practice it in the future.

How has being overlooked shaped your life personally?

It’s affected me in all ways on all days. It’s never not affected me and it’s not that I’m guessing. I’ll just give one example. It’s affected me financially over the course of my career. And I say this because I’m married to a man who has had the same jobs that I’ve had in this business. And so I’m privy to what his salary has always been as compared to what mine has always been. It’s insane the difference, and he’s a Black man. I can’t imagine the difference, or I should say, I can very clearly imagine, how much more different it would be if he was a white male.

What was your creative process like in curating the book?

It changed as I became more committed to getting it done. At first, it seemed like a cool project that I needed to do, so I would devote the time to it, and that was convenient for me. I was teaching and then I was at ESPN, and I was doing a lot of writing, editing, and producing at ESPN. It didn’t leave a lot of time for doing my best work outside of the main job. But then when I started working again with (publisher) Chris Jackson at One World, he was asking me why I wasn’t finishing the book, and I had no good answer for him, especially because I wanted to finish it. And he said, “I think you need to claim your space as a Black woman in pop music and write about your experiences as it relates to the experiences of the women that you have so beautifully written these biographical essays about.” And after a little resistance, I took that advice.

I had great support from my husband. I had great support from my sister and that gave me the courage to resign from ESPN and work on my book full time. And it really was an amazing experience. I put myself on a pretty religious schedule of rising at 4 a.m. and writing until 11:00 a.m. It was so great. My morning mind is lush so I was getting stuff done. And when I say writing from 4 to 11, it’s a combination of research and writing, and then it became a combination of research and refining. And then I finally finished, it was a battle at the end, but I’m finally finished and really it’s changed my life.

The book reads not only like an anthology, but also like a journey into Black history. Was that inevitable?

I don’t think that you can talk about culture without talking about the sociopolitical climate. And my book is very specifically about Black pop created by Black women. There’s so much ambition in the sound. ... I began to ask myself, “Where does this come from? Why is it so intense? Why is it so successful? Why is it so influential?” And one of the many things is that so many of the women were born into segregation. I wanted to know where that sound, that striving for bigness and perfection came from. And I think it comes from being treated unfairly, being treated with ugliness, being forced into a caste system.

In the case specifically of [singer] Marilyn McCoo, her [pregnant] mother used to take a train all the way up to New Jersey to go to a Black gynecologist there, wait till her infants were old enough to travel, and then go back down South where [McCoo] was raised. To me, that is just an incredible story not to know about a woman who has eight Grammys and influenced the culture as McCoo and The Fifth Dimension did. These are just the kind of details that are amazing to me that we just don’t know.

I had to write about the fact that Diana Ross’ family spent time struggling in the projects [in Detroit]. The benefits of the GI Bill were rarely if ever made available to Black soldiers returning home. So [Ross’ father] had to come back home and figure it out for himself, when the white veterans coming home were getting their college tuition paid for and receiving low interest loans to buy homes. But he had to be in the projects with his family, and that has an effect on Diana, as much as growing up listening to people like Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday had on her sound and her desire to become a Supreme. I mean, that’s a hell of a name. Even the Primettes [the group’s first name] is a hell of a name.

So that’s why it’s so important to have that kind of historical context. Music doesn’t just come out of nowhere. When we were in the fields, it came from the pain of all of that. So why wouldn’t the sound of Black pop come from something as well?

Terms such as “pop” and “diva” are used in a derisive fashion, but you use them with a sense of empowerment. How were you able to do that?

It’s super funny to me that when Black people achieve or arrive at some type of cultural destination, now that destination isn’t as cool or as wonderful as it was before Black artists arrived there. One of those spaces is the top of the pop charts. It was the ultimate thing that you could do outside of winning a Grammy in the music business, going No. 1, and then Motown started doing it with regularity. The Supremes battled the Beatles, and they were going punch for punch in the ’60s. And we see how much more the Beatles are uplifted than the Supremes are in our culture.

In the 1970s, you have disco. The spine of disco is Black women. And so it was immediately looked upon by even a lot of conservative Black mainstream figures as something less than, not as good as proper rhythm and blues, which is all disco is – it’s just rhythm and blues. It’s Black music. And then mainstream white artists looked upon disco as just a field from which to pluck inspiration and basically regurgitate it.

And then you get to the ’80s. And this is the one that really flipped because what Motown, and then disco, set up was the culture-shattering careers of Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, and Lionel Richie, who achieved the kind of pop success that had never been achieved before. So then all of a sudden “pop” became a dirty word. Going pop was “whack” and you were “selling out.” So yes, I want to reclaim pop. ... It means being the most popular. Pop is the people’s choice and Black pop is the world.

I’m in the business of reclaiming that as I reclaim “diva,” as you mentioned, which is a whole thing that deserves its own book, honestly, but yes, reclaiming all of that, like stop calling stuff other than what it was. I’m fascinated by acceptance speeches and I need to find it, I was watching in real time when Carlos Santana … held [his] award up and said something to the effect of, “All of this is Black music and all of this comes from Africa.” So yes, I’m in the business of reclaiming Black women’s time.

How did you find a balance in your book between sorrow and solace? Or, as Maze might put it, “Joy and Pain”?

There’s a reason why many people consider that song to be one of Black America’s national anthems. It’s an emotional topic for me because music is such a great hiding place. You don’t have to hear the world. A lot of times, you don’t have to hear your own thoughts. Then you begin to allow yourself and the music to kind of become one. You have your favorites, what makes you feel better. You know, what gets you amped up. What saves your life. And then if you’re as lucky as I am, you become a super fan of the work itself, of what it takes to make music, and you let that inspire you over the course of your own life and inspire you to do your best work.

And I think I said in the introduction, where I would be in my life if not for music? I know so many Black people of my generation and Gen X who say they don’t know where they would be in their life without hip-hop. I’ve spent a career trying to explain, and I try to explain and shine bright. And I don’t know the degree to which I am successful in explaining what music really does for us, how it serves us and we serve it. But all I can continue to say is that it saves my life. So of course there’s joy and pain and there’s everything in it.

Is there anything or anyone else that you wanted to get in the book?

I wanted to get everybody in the book. The only way that I was able to finish the book was to limit it to the Black women in pop who have meant the most to me and my sister, who have meant the most to my mother and her sister, and who have meant the most to my grandmother and her sister. That’s the only way. And when I say meant the most to me, I mean the most to me professionally and personally, but there’s a zillion women. I would love to write a whole series of books just about Sade. It was hard not to write more about Aretha Franklin and as it is, her chapter and Whitney’s chapter is, like my editor called it, a book within a book. Oh my goodness. There’s not enough Mary J. Blige, not enough Ella Fitzgerald, Donna Summer, Linda Peaches from Peaches and Herb, Jody Watley, the list goes on.