In the story of women’s rights, diverse voices add depth

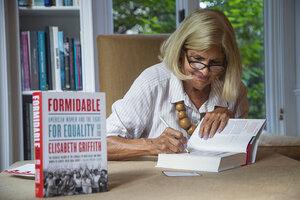

Elisabeth Griffith, an acclaimed biographer of Elizabeth Cady Stanton who has been teaching and writing about women's history for 40 years, highlights a diverse cast of characters in her new book, "Formidable: American Women and the Fight for Equality 1920-2020." She signs copies of her book at an event in Washington on Sept. 18, 2022.

Christa Case Bryant/The Christian Science Monitor

The story of how women got the right to vote is a fascinating nail-biter that came down to one vote in Tennessee. But then what? Many didn’t – or couldn’t – vote.

So Elisabeth Griffith wanted to know: If women weren’t voting, what were the obstacles? She found answers by delving into the different priorities of Black and white women, and the tensions those created – a dynamic often overlooked in tomes on women’s history.

“Formidable: American Women and the Fight for Equality 1920-2020” starts with the certification of the 19th Amendment and ends with the confirmation of Donald Trump nominee Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, an arc that Dr. Griffith says highlights the diversity of the women’s movement.

Why We Wrote This

The struggle for equal rights was carried out by Black and white women, but their contributions were not equally acknowledged. A historian shows how a diverse array of voices enriched the women’s movement.

Dr. Griffith knows a little about that herself; as a young college graduate, she got involved with the newly formed National Women’s Political Caucus, the bipartisan and interracial political arm of the women’s movement. Now an acclaimed biographer of Elizabeth Cady Stanton with 40 years of teaching and writing women’s history under her belt, she traces the stories of a large cast of characters – many heroic but largely unknown – in her latest book.

Though a self-proclaimed optimist, she says women still have far to go. After 75 years, for example, the share of full-time college faculty members has increased only 5%, to not quite one-third. And, she adds, the women’s movement has lost ground with the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in June that overturned Roe v. Wade.

Dr. Griffith spoke with the Monitor about what she learned in writing “Formidable” and what it means for women’s rights, for men, and for American democracy. The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

You’ve been credited with providing a more inclusive look at women’s struggle for equal rights. Why did you decide to write this book?

Until women’s history becomes a formal field around 1970, everything that ever happened in America seemed only to happen to white men. So white women historians are insisting, we want to be visible – and then seem to neglect that there are other people whom they could be making visible at the same time.

There were African American women writing from the start. But many of the books written about the progress of women since 1920 have focused primarily on white women, unless they’re written from a specifically Black point of view, and covering a Black topic within that chronology. That intrigued me. I wanted to know more about it. The sources were deep-rooted racism and segregation – and distrust by Black women of white women, because at various points in American history, they had been treated not well.

But there are moments when they are allied. From 1915 to 1920, Carrie Chapman Catt is able to create a multiracial, multigenerational national campaign. It’s brilliant. And then it splinters, because everybody who wanted the right to vote wanted it for different reasons. And those reasons were sometimes competitive.

After 1920, white women did not take up the cause of Black women, who now have the right to vote but are discriminated against at the state level. White women think that’s not their fight anymore, which was really a missed opportunity for them.

So there are lots of complications to the story. And most of the parts of it had been told by other scholars. But I made the effort to tie it all together in one book.

What are some of the differences in how Black and white women pursued equal rights that have been overlooked in women’s history?

I would argue that we weren’t as successful as we would like to take credit for, because it didn’t reach as many people as it should. You can’t just stop with a privileged, educated cohort.

It’s one of the tensions between Black and white women, because white women would say, “We got all these political rights.” But if you’re talking about food deserts, the lowest-paid kinds of jobs, or rates of incarceration, or racial violence, or police violence – those need to be the agenda of the women’s movement, too.

White women wanted the rights of white men and had a political agenda with some social change, like wearing trousers to work. Black women from the very first wanted to safeguard the community. They were working for male and female; it was an entire community movement. They wanted to get rid of lynching. They want to get rid of Jim Crow. They wanted to get rid of every form of repression that segregation allowed. So it always had a much broader base.

And it was harder for them. White women could function in the world without risking their husband’s job, their own job, physical violence, or being thrown into jail. Black women were always aware of the risks to them or their families. When Ruby Bridges integrates the school in New Orleans [in 1960], her grandparents are thrown out of their rental building. And her parents lose their jobs.

You have said we study history to learn and to be inspired and to be chastised sometimes. What do you think we need to be more humble about regarding women’s history?

I have a Ph.D. in American history, and I learned at least as much as I had already known to write this book.

You cannot generalize about women in America, because there are all kinds – every political point of view, religious, regional, ethnic, racial, educational, whether they’re married or not, whether they’ve had children or not, all the sexuality issues – women are very diverse. And they all have different views on every topic, including against most of the things that the activists in my book were for. So you have to take into account a lot of players.

I feel very strongly about history. I almost think it’s a civic duty to know American history. A fact-based history that includes the good and the bad shows the strength of American democracy. We shouldn’t be afraid of it. I would hope that it would inspire greater civic pride and participation.

What inspired you most in writing this book, and what gives you hope about women’s struggle for equal rights going forward?

My cohort of female friends graduated at the cusp of a second wave of women’s activism. I came to Washington in the early 1970s, and was marching and lobbying and working for things. And they happened. So that gave me a sense that the system worked.

I don’t think the system works anymore. But as a teacher, I also have faith in young people. I keep trying to say to myself that the best thing about the Dobbs decision will be that it will energize a new generation of young people who have benefited from so many changes and have no recollection that they even had to earn those rights.

The numbers of people who are registering to vote and the Kansas vote [on abortion] are quite reassuring. I have to say I’m really annoyed that that many people were not registered to begin with, though. What were all these 18-to-45-year-olds doing? Do they know that people went to jail? Do they know that people got beaten up and killed? Why aren’t they voting? It’s a responsibility.

Do you see women as having a particular role in addressing the deep divisions in our country right now?

I think we all need to work on that. But I do think women have gifts for connecting through conversation and finding common ground. There’s just evidence of that forever in American history, and in other cultures as well.

We’ve got to start somewhere. And for me, it would be with people who vote for people I don’t like. So how do I open that conversation? I grew up a Republican, and I still have some friends and relatives who are. We find so many things in common. The government ought to work; people ought to come together and solve this problem; you could start with something small and then fix the next step.

The women who are registering to vote are both Republican and Democratic women, and the common ground is reproductive rights. So that is heartening to me, because maybe it means we can begin to find more common ground among women in different parts of the political, economic, and racial spectrum.

We need to find ways to repair this country and women can be good at that.

Is feminism good for men?

If you go to the most basic definition [of feminism] – equal social, economic, and political rights with men – it ought to be a rising of all boats.

I wish people would not see it as a threat. But I think sometimes – this is certainly true politically – you think that if you expand a right to somebody else, somebody has lost something.

I have always been related to feminist men. My father had only daughters. My husband was a fabulous feminist who marched with me and was on the NARAL [an abortion-rights organization] board.

I can’t imagine that men who love the women they live with or were raised by do not want them to have equal rights.