Countdown

A 12-year-old faces down the Cuban Missile Crisis in this highly appealing coming-of-age story for middle-school-age readers.

Countdown

By Deborah Wiles

Scholastic

400 pp., $17.99

Ages 9-12

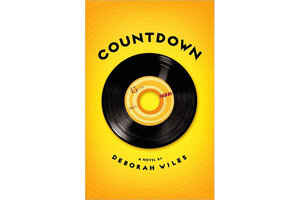

Even the 45 r.p.m. record pictured on the book jacket of Deborah Wiles’s newest novel feels real – vinyl, black, shiny, and just begging young readers to come in and explore.

Set in 1962, Countdown is fifth-grader Franny Chapman’s story to tell. Her dad serves in the Air Force and is often absent from home. Her mother is long-suffering, overburdened. Franny looks up to her sister, a college student with a shadowy parallel life, and tolerates her younger brother, the perfect child. Pretty much a run-of-the-mill 1960s family so far.

Then there’s Uncle Otts, a World War I veteran, convinced the bomb is about to drop and that the Chapmans’ Maryland town will be targeted. Although her uncle sometimes embarrasses her, Franny, and especially her brother, worry that he may be right. Perhaps their secure world is about to explode. Why else would teachers admonish them to “Duck and Cover!” and why would the Cubans aim their missiles at the elementary school playground?

Wiles’s novel – the first in a trilogy about the ’60s – revolves around the Cuban Missile Crisis, but it’s more than history. Franny’s friendships are as tangled as any contemporary 11-year-old’s. Her budding crush on the nice-as-can-be Cute Boy and her changing relationship with her sister could take place anywhere, anytime. That’s just one of the many reasons this book will be a huge hit with middle-grade readers.

Even the minor characters are written to perfection. Franny’s teacher, who appears to be an aggravation, plays out as a perfect twist to the story’s ending. Her uncle, afflicted with post-traumatic stress disorder, digs up the yard for his bomb shelter, suffering a humiliating breakdown in front of the neighborhood. Yet he manages to endear himself to his family.

“Countdown” is billed as a documentary novel, a mostly new genre in kids’ books. Flowing, collagelike, throughout the story are photographs, music, and even reports that sound remarkably like fifth-grade social studies assignments on historical figures (Harry Truman, the Kennedys, civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer).

Whether young readers will decipher the lyrics, the newspaper headlines, and the facts on the same level as adults more familiar with the events of 1962 doesn’t really matter. Reading Wiles’s remarkable new book, they’ll now experience the history and story through the eyes and heart of funny, appealing, conflicted young Franny Chapman. And, after all, that’s what savoring a truly great book is all about.

Augusta Scattergood frequently reviews children’s books for the Monitor.