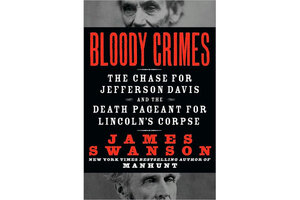

Bloody Crimes

Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis: Two journeys, two martyrs in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Bloody Crimes:

The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln’s Corpse

William Morrow

480 pp., $27.99

Just days earlier, they were two presidents who lived in White Houses separated by a few dozen miles and a canyon as wide as the world.

Now one was dead and the other on the run, both embarking on journeys that would help transform them from men to martyrs. One became a country’s savior and the other a noble leader whose lost cause, at least to some eyes, was just.

How’d it happen? Civil War historian James Swanson finds the answer in his eloquent and wrenching new book, Bloody Crimes: The Chase for Jefferson Davis and the Death Pageant for Lincoln’s Corpse.

Only one of the dual voyages is truly extraordinary, and the book lacks the high-tension suspense of Swanson’s 2006 bestseller “Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer.” This time, he has less drama to work with. But he continues to serve as the Ken Burns of history-book storytelling, capturing the incredible emotions that swirled through a divided nation already torn by the war deaths of 620,000 men.

As Swanson puts it, the spring of 1865, when the book’s events took place, “was the most remarkable season in American history.” That’s no exaggeration: Within days, the Civil War essentially ended and the North celebrated while weary, hungry, and frightened Southerners waited for the worst. Then came one more death at Ford’s Theatre.

This is a familiar story, one that Swanson tells well. He digs deep, chronicling the parade of death that had already struck Abraham Lincoln and his White House. As friends and strangers died in the war, the president wrote letter after letter to widows and parents, preserving his agony in ink on paper. Then one of his sons, his favorite, passed away. Yet he persevered and guided his nation to victory.

When it was the public’s turn to grieve for him, the North unleashed a torrent of mourning as if all their pent-up emotions were let loose upon the land. They mobbed the train that carried his body home to Illinois with a level of mourning never seen before or since.

“His traveling corpse became a touchstone that offered catharsis for all the pain the American people had suffered and stored up over four bloody years of civil war,” Swanson writes.

The words “death pageant” in the book’s title hint at the morbid nature of Lincoln’s voyage, and it certainly sounds gruesome at times. But the acts of remembrance by men, women, and children are truly moving, coming during a time when there were no grief counselors or tsk-tsking commentators telling everyone to calm down. Armed with ribbons and signs, speeches and songs, tears and oceans of black crepe, they paid tribute and burnished a legend.

The Confederate president’s voyage, meanwhile, was not attended by millions or even thousands. Jefferson Davis fled south from Virginia, stubbornly seeking to continue the war while passing through exhausted Southern towns that often wanted little to do with him.

A couple of the largest players in “Bloody Crimes” are places instead of people: Washington, D.C., and Richmond, the Confederate capital. One is doomed to burn – but not before being visited by a brave (or foolhardy) Lincoln – and the other destined to launch a grand war-ending celebration cut short by an actor, a bullet, and a conspiracy. Swanson uses the voices of their residents to bring both cities alive.

But Swanson doesn’t always sail smoothly through his story. While he paints Davis’s wife, Varina, as a selfless helpmate, he unfairly turns the complicated Mary Todd Lincoln into a one-dimensional harridan. Although hardly an appealing figure, she deserves better.

At the same time, Swanson paints a portrait of a Confederate president who’s worthy of respect and not “a humorless, arrogant, inflexible, racist, slave-owning traitor.”

If it’s dishonorable to lead an ignoble cause, then his reputation should be as hollow as the statues that bear his craggy face. But his actions after the Civil War solidified his heroic status in the South, where counties and public schools still bear his name.

Indeed, Davis gained a victory of sorts despite the embarrassing (and exaggerated) end of his military and political career. As he solidified into “a fixed symbol in a changing age,” the South’s image of itself rose again, accompanied by a fervent defense of the “Lost Cause” and the spirit of a onetime president.

As for Lincoln, he finally made it home to Springfield after breaking the hearts of millions. Their numbers will grow even larger thanks to this book.

Randy Dotinga regularly reviews books for the Monitor.