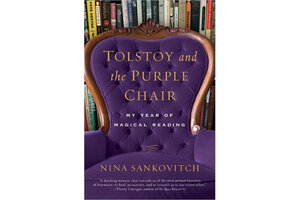

Tolstoy and the Purple Chair: My Year of Magical Reading

How one woman used books to cope with her sister's death.

Tolstoy and the Purple Chair: My Year of Magical Reading, By Nina Sankovitch, Harper Collins, 265 pp.

An avid reader isn’t necessarily a deep writer. This may be the key to the profound limitations of Nina Sankovitch’s Tolstoy and the Purple Chair: My Year of Magical Reading, an amateur memoir of loss pegged to her eldest sister’s death. The book owes its subtitle to acclaimed journalist and novelist Joan Didion’s own 2005 account of exquisite grief at the deaths of both her husband and daughter, in “The Year of Magical Thinking." But Sankovitch boasts none of Didion’s brilliance – at least, not as an author.

Trained as an attorney, Sankovitch, 48, does her due diligence in this stolid recapping of the 12 months that she spent reading a book a day, as a salve for losing an adored sibling to cancer several years before. Every tome that she picks up is exhaustively detailed, along with any similarity that its heroine bears to her idealized late sister, Anne-Marie.

Not that Sankovitch isn’t bright; she earned her J.D. at Harvard. But a lack of independent thought marks her narrative of the family life created in the US by her Catholic immigrant parents – an academic and a doctor from Belgium and Belarus, respectively – along with her parroting of their tales of suffering endured by European relatives during World War II, all without wonder at their conclusions.

On learning that three of her father’s siblings were executed by partisans while his mother hid in an adjoining room, Sankovitch never asks an obvious question: Why didn’t she intervene? Instead, the lawyer offers what sounds like a sermon. Her grandmother was “unable to save them,” she says of her aunt and uncles, then intones, “But remembrance is the bones around which a body of resilience is built.”

Exculpating explanations aside, if survivor guilt is a family legacy that’s dropped by one generation onto the shoulders of the next, then the weight of it seems to have settled on Sankovitch. What drives her memoir is an outsized sense of responsibility for her sister’s death – or at least, for enduring when her more meritorious sibling (in Sankovitch’s view) cannot. “Why do I deserve to live?” she moans.

It’s a question that spurs her to seek comfort in a regimen of reading. “I was reminded of Anne-Marie in the characters I was meeting,” Sankovitch swoons. “She was the kind of heroine authors like to put in their books, with her quiet strength and resilience, her utter lack of petty or trivial concerns, and the superlative combination of her beauty and her intelligence,” the author continues. “Anne-Marie had her negative traits, but even those always seemed to me to be ubertraits.”

Quite a mash note. What did Anne-Marie do to earn such adulation? Her virtue seems to rest largely on having stopped the author, at age 12, from riding the wrong bus into a down-at-heel district of Chicago, one with bars, liquor stores, pawn shops, and decrepit apartment buildings.

“’You saved my life,’” Sankovitch recalls gasping to her sister at the time. Four decades later, she never really reconsiders the drama of her statement or leaves off its adolescent credulity.

That makes her memoir not complex but rather sweet, profoundly sincere, and wholly devoted to its subject: the search for sustenance in the face of sorrow. The book’s lack of skepticism may fail to spark reader interest in the author’s close relationships. But it’s intriguing at least for the role that ritual plays in her grasp at meaning.

Facing guilt or loss, some turn to old rites: making confession, sitting shiva, or gathering together with friends. In this age of the self, however, Sankovitch has adapted the tradition of shared mourning into a novel form of solace. Hers consists of curling up with a book a day – and then posting a review of it, the next day, online.

In fact, she developed a following for her blog, ReadAllDay.org, and fans wrote to suggest favorite titles. “I received an e-mail from a man in New York City who had been doing research for a book club meeting,” she gushes, adding, “He and I, complete strangers, made a connection through our love of books. A reader reached out from Germany, the sister of a friend wrote from Brazil,” she enumerates, and “a woman wrote from Singapore, and I had a whole slew of British book lovers writing in with recommendations.”

Whether or not such effusing makes for a strong memoir, it’s a marker of the times. Calling into the void for reassurance is a universal trend. Through the magic of cyberspace, sometimes – often – someone replies.

Susan Comninos is a journalist and poet in New York. Her articles recently appeared in the Forward and Albany Times Union. Last year, she won Tablet Magazine’s Yehuda Halevi Poetry Competition